23 Jaundice and pruritus

Case

A 50-year-old female presented with a 2-week history of episodic right upper quadrant pain that radiated around the costal margin to the back. Similar pains had occurred over 5 years. The current episode had persisted, although fluctuating over several days with the development of jaundice, pale stools and dark urine. Serum alkaline phosphatise was 400 IU/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 300 IU/L. Physical examination revealed a jaundiced patient in obvious discomfort with right upper abdominal quadrant tenderness. An abdominal ultrasound examination was performed. This revealed no cholelithiasis but a dilated common bile duct of 1.2 cm diameter; no stones were seen. Subsequently, an endoscopic ultrasound study demonstrated a gallstone within the distal common bile duct. At endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy, the stone was removed. The patient’s symptoms and biochemical abnormalities resolved. She subsequently underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy and remained well.

Introduction

Jaundice is yellow pigmentation of the sclera, skin, and mucous membranes caused by deposition of bilirubin in tissue. Jaundice becomes apparent when the serum bilirubin level rises above 50–75 μmol/L (normal: 3–15 μmol/L). It is most often associated with hepatocellular dysfunction or cholestatic syndromes including biliary obstruction, and is often associated with pruritus. The history and physical examination of the patient with suspected liver disease and an approach to abnormal liver function tests are discussed in Chapter 24. Here, bilirubin physiology and diagnostic methods are outlined, focusing on the clinical approach to patients with obstructive jaundice.

Physiology

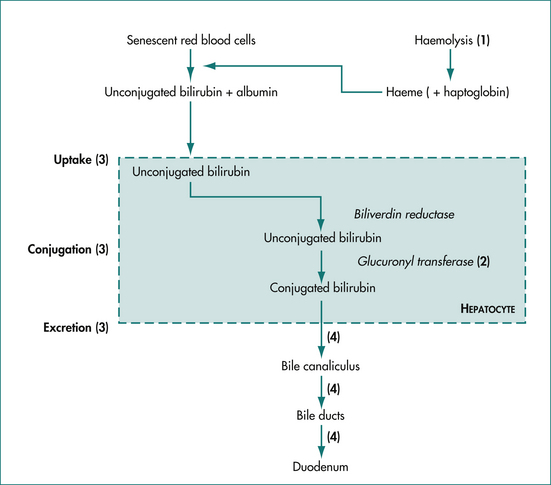

Jaundice results from either increased production and/or decreased excretion of bilirubin. The metabolism of bilirubin is summarised in Figure 23.1. Under normal conditions, 80% of serum bilirubin is generated by senescent red blood cells, which are broken down by the reticuloendothelial system in the spleen, liver and bone marrow. The released haeme (ferroprotoporphyrin IX) is oxidatively cleaved to biliverdin and then bilirubin, which is tightly bound to albumin and transported in the serum. The other 20% of serum bilirubin arises from the breakdown of other haeme-containing proteins (e.g. cytochrome, myoglobin and haeme-containing enzymes) and ineffective erythropoiesis (the premature breakdown of red cells in the bone marrow before release). Bilirubin, which is lipid soluble, is made water soluble by conjugation in the liver.

Jaundice may be caused by obstruction or overloading at various points in the bilirubin metabolism pathway (Fig 23.1). The proportions of conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin detected in the serum depend on the site of the obstruction or overloading. Haemolysis or reabsorption of a haematoma leads to an unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia because the hepatocytes become overloaded. Reduced uptake and rates of conjugation will likewise lead to increases in serum unconjugated bilirubin.

Measurement of serum bilirubin

The normal range for serum bilirubin is 3–15 μmol/L in adults. Bilirubin is classified as direct (conjugated) and indirect (unconjugated). This terminology is derived from the commonly used assay that makes use of a diazo reaction. Diazotised aromatic amines cleave the bilirubin molecule into two identical molecules, which are bound to the azo compound. These are measured spectrophotometrically. In an acidic aqueous media, conjugated bilirubin reacts ‘directly’ with the azo compound; whereas unconjugated bilirubin requires the addition of an accelerator molecule such as alcohol, thus reacting ‘indirectly’.

The causes of jaundice are typically classified into three groups corresponding to the site of impaired bilirubin metabolism: prehepatic, hepatic and posthepatic (cholestasis, obstruction). This classification is clinically useful when evaluating patients with jaundice or hyperbilirubinaemia. There are distinctive clinical features and liver function test profiles and clinical presentations for each group (Table 23.1). These help the physician to identify the likely site of impaired bilirubin metabolism, narrow the differential diagnosis, and then order the most appropriate investigations.

Table 23.1 Clinical features and liver function test profiles in hepatic (hepatocellular) and cholestatic (or obstructive) jaundice

| Suggests hepatocellular jaundice | Suggests obstructive jaundice | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | Nausea, anorexia, fatigue, myalgia, known infectious exposure, IV drug use, blood transfusions, alcohol, medication abuse, positive family history of liver disease or jaundice | Pain, pruritus, dark urine, pale stools, fever, past biliary surgery, weight loss, older age |

| Transaminases (AST, ALT) | ++ (> 3 × normal) | + (< 3 × normal) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Normal to increased (< 3 × normal) | ++ (> 3 × normal) |

| INR or prothrombin time after vitamin K | Does not correct | Corrects if extrahepatic obstruction |

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; INR = international normalised ratio.

Prehepatic jaundice

Isolated unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia is a common clinical problem. Patients typically present with mildly elevated serum bilirubin but normal levels of serum transaminases and alkaline phosphatase (refer to Ch 24 for a detailed discussion of liver function tests). The serum bilirubin is almost entirely unconjugated. Hepatocellular function and biliary excretion are normal.

Hepatic jaundice

Hepatic jaundice may be acute or chronic in origin. These two groups have different clinical presentations and liver function test profiles, but there may be considerable overlap. The level of hyperbilirubinaemia can vary greatly and it is seldom a clue to the diagnosis (Ch 24).

Obstruction or cholestasis

Obstructive jaundice occurs when bile flow through the extrahepatic biliary tree is impaired, usually by a stone or tumour. Intrahepatic cholestasis occurs when excretion of conjugated bilirubin from the liver cell into the bile canaliculus is disrupted. The most common cause is a drug reaction, but some cases of viral hepatitis and some chronic liver diseases (e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis) can also cause cholestasis.

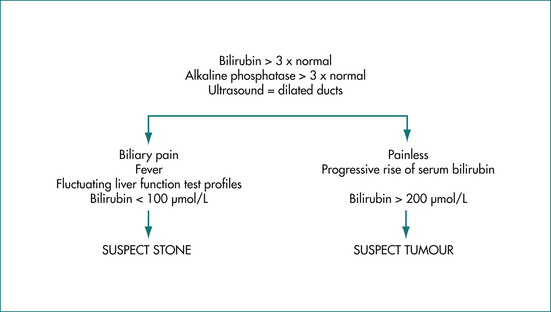

The clinical features and liver function test abnormalities produced by cholestasis and obstruction are similar. Both present with prominent jaundice, dark urine and pale stools. Pruritus may be present if the cholestasis or obstruction is longstanding. The serum alkaline phosphatase level is usually greater than three times the normal level, transaminases are usually less than three times normal, and serum bilirubin concentration is elevated. It should be noted that in acute biliary obstruction, as may occur in choledocholithiasis, serum transaminase levels rise earlier than the alkaline phosphatase. The prothrombin time may be prolonged due to poor absorption of vitamin K but is rapidly corrected by administering parenteral vitamin K in obstruction. Constant pain in the right upper quadrant may be present. Severe episodic pain lasting a few hours suggests stones in the bile duct. Painless jaundice is the hallmark of malignant biliary obstruction commonly seen in patients with pancreatic cancer (Ch 17) (Fig 23.2).

Clinical Syndromes

Prehepatic jaundice

Gilbert’s disease

Other causes of unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia are bilirubin overproduction, impaired uptake by hepatocytes, or impaired delivery to the liver (Table 23.2).

Table 23.2 Mechanisms for the development of unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia with typical examples

| Mechanism | Example |

|---|---|

| Impaired conjugation | Gilbert’s syndrome |

| Impaired uptake | Drug, e.g. rifampicin |

| Overproduction: | |

Bilirubin overproduction

Overproduction arises from accelerated red blood cell destruction and is a common cause of prehepatic jaundice. Examples include chronic haemolysis seen in patients with prosthetic heart valves, hereditary spherocytosis and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, or acute intravascular haemolysis seen in patients with sickle cell crisis or transfusion reactions. Haemolysis can be diagnosed on the basis of a characteristic blood film, low haptoglobin and high lactate dehydrogenase levels.

Cholestatic and obstructive jaundice

Intrahepatic cholestasis

Viral hepatitis, particularly hepatitis A, can occasionally cause intrahepatic cholestasis. Acute hepatitis A can cause a cholestatic hepatitis with an elevated alkaline phosphatase level, fever, arthralgia and jaundice lasting 2–8 months. When chronic alcohol consumption leads to significant fatty infiltration of the liver, cholestasis can also occur. These diseases are discussed in Chapter 24.

Extrahepatic obstructive jaundice

Extrahepatic biliary obstruction is usually caused by either stones or tumours. About 80% of patients with stones in the bile duct have biliary pain (Ch 4). This is severe abdominal pain that is constant in nature rather than colicky, localises to the epigastrium (or right upper quadrant if cholecystitis intervenes), and may radiate around or through to the back. The pain lasts 30 minutes to several hours and occurs episodically. Obstruction due to stones is often intermittent, so the level of jaundice may fluctuate. The obstruction is less complete than that seen with malignancy and the serum bilirubin level usually does not rise above 100 μmol/L. There is often an abrupt rise and fall of transaminase activity over 48 hours coinciding with the pain.

On the other hand, tumours usually cause painless jaundice. There may be associated weight loss. Fever is unusual and suggests the development of cholangitis. As the obstruction becomes more complete, the level of serum bilirubin increases steadily and is often greater than 150 μmol/L at presentation. An ultrasound scan performed to differentiate between the two causes of obstructive jaundice may identify stones within the ducts or a tumour mass. However, equivocal results are not uncommon.

Tumours causing obstruction of the bile duct include carcinoma of the pancreas or gallbladder, cholangiocarcinoma and metastases to hilar lymph nodes. Carcinoma of the pancreas is most common and causes obstruction of the lower bile duct where it passes in a groove behind the head of the pancreas before entering the duodenum. It is an aggressive tumour that locally invades or obstructs the major vessels which transverse the pancreas, and metastasises early to the lymph nodes and liver (Ch 17). Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater is an uncommon tumour that may present with progressive obstructive jaundice but can also mimic choledocholithiasis and present with cholangitis or pancreatitis. It is important to distinguish ampullary carcinoma from carcinoma of the pancreas as it is a relatively slow-growing tumour and surgical resection produces a cure in more than 40% of patients.

Chronic pancreatitis may also cause stricturing with obstruction of the low bile duct where it passes behind the head of the pancreas. The duct is compressed by fibrosis and oedema within the pancreas (Ch 6). There is usually a long history of chronic alcoholic pancreatitis and care needs to be taken to distinguish the change in the liver function test profile due to alcoholic liver disease from that of biliary obstruction.

Diagnostic Tests

Laboratory evaluation

A detailed history, thorough physical examination and routine laboratory evaluation yield the diagnosis in most instances. Clues to the diagnosis of various diseases have been mentioned in previous sections. Routine biochemical tests of liver function are simple, cheap and yield much useful information (Ch 24). Once this has been done, appropriate serological and radiographical studies can be performed to establish the definitive diagnosis.

Organ imaging

The results of imaging must be interpreted together with the clinical history and laboratory investigations. If a radiological test is not consistent with the clinical impression, consideration should be given to further imaging. A comparison of the various imaging modalities is shown in Table 23.3.

| Test | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound |

Ultrasonography

An ultrasound scan is simple, widely available, and is the initial test of choice in suspected obstructive jaundice. It accurately identifies the bile duct diameter (Ch 26), although it should be noted that the bile duct diameter may be normal shortly after the onset of obstruction. This problem is avoided by repeating the ultrasound scan 5–7 days after the onset of jaundice. It should be remembered that the common bile duct dilates after cholecystectomy. Stones in the gallbladder are readily identified, with a false-negative rate of only 5%. Stones in the bile duct are more difficult to identify because the duct passes behind the air-filled duodenum. The false-negative rate in this instance approaches 70%. Ultrasound examination can identify primary tumours in the pancreas, gallbladder and bile duct, and liver metastases. Real-time ultrasound with Doppler flow studies has an advantage over computerised tomography in that it can assess the patency of the portal vein, hepatic artery, inferior vena cava and splenic vein. This is useful in staging tumours, identifying portal hypertension, and identifying vascular thrombosis. Obesity, distortion of the normal anatomy from previous surgery and the presence of intestinal gas obscuring the area of interest can detract from the accuracy of this examination.

Endoscopic ultrasound

Ultrasonography from the duodenum allows good views of the bilary tract. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can be useful in the evaluation of jaundiced patients where ultrasound and CT scanning have not revealed the cause of obstruction. It can be particularly useful in evaluating pancreatic masses, common bile duct stones and masses in the hilum of the liver. Small pancreatic lesions not well seen by other imaging methods can be identified. Furthermore, fine needle aspiration biopsy can be obtained from mass lesions identified at EUS. When choledocholithiasis is suspected, EUS can be used as the preliminary investigation, avoiding endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in two-thirds of patients. This approach significantly reduces the risk of procedural complications such as pancreatitis. This technique has similar accuracy to ERCP in detecting stones in the common bile duct.

Liver biopsy

Biopsies are not typically required for the evaluation of jaundice unless intrahepatic disease is suspected (Ch 24). They are usually reserved for the evaluation of suspected hepatocellular or infiltrative liver disease.

Intravenous cholangiogram

X-ray tomography of the bile duct is performed after an intravenously introduced contrast agent is excreted by the liver into the bile ducts. A raised serum bilirubin level precludes uptake of the contrast agent by the liver so the test is useful only for identifying stones in non-obstructed ducts. In the past, intravenous cholangiography has not often been used because of allergic reactions to the contrast agent and poor accuracy. The recent development of new contrast agents with fewer adverse reactions and the use of CT scanning to improve accuracy may see this test used more often in the future.

Management of Suspected Obstructive Jaundice

Bile duct obstruction

Patients with suspected obstructive jaundice should be initially investigated by ultrasonography. If the bile ducts are not dilated, the causes of intrahepatic cholestasis need to be considered (Ch 24); for example, the patient’s drug history should be re-examined, and checks made of viral serology (e.g. hepatitis A), autoantibodies (for autoimmune hepatitis) and antimitochondrial antibody (for primary biliary cirrhosis). Liver biopsy may sometimes be needed for a definitive diagnosis. Treatment must be directed at the underlying cause and, where necessary, managing the complications of irreversible liver disease.

Patients with dilated ducts usually have stones or a tumour.

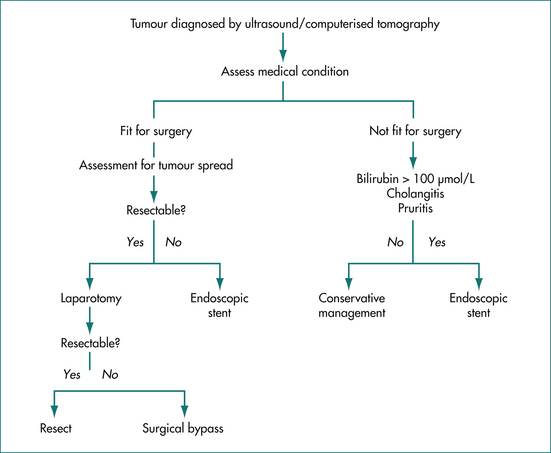

Tumours

Carcinoma of the pancreas is the most common tumour that causes biliary obstruction (50–60% of tertiary referrals) (Ch 17). The principles of management are similar for other tumours such as cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma (Fig 23.3). A good quality ultrasound examination will usually identify the tumour mass and the site of obstruction in addition to any liver metastases. If the ultrasound results are equivocal and clinical suspicion is high, then a CT scan may give more information. An EUS can provide further detailed assessment. Occasionally cholangiography by MRI or ERCP is required to define a small pancreatic or bile duct lesion.

If the patient is fit for surgery, and does not have evidence of tumour spread to lymph nodes or liver, then further assessment for surgical resection may be worth undertaking, although none is routine. Useful investigations may include:

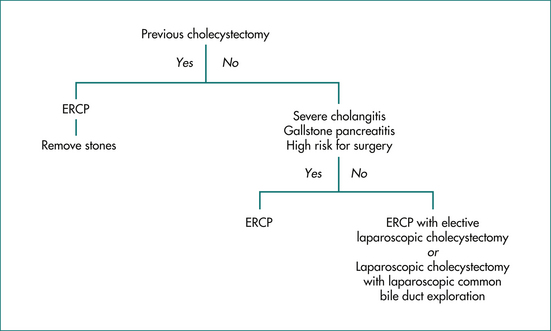

Stones

For the purpose of planning management, patients with stones in the common bile duct can be divided into those with and those without a gallbladder (Fig 23.4). In patients who have had a cholecystectomy, ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction is the treatment of choice. Patients with their gallbladder in place have several treatment options. Those who are at high risk for surgery, have severe cholangitis, or have severe gallstone pancreatitis should be treated with ERCP, sphincterotomy and stone extraction. Cholecystectomy can be considered after their other medical conditions have stabilised. In young, fit patients with choledocholithiasis and the gallbladder in situ, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has largely replaced open cholecystectomy. Some surgeons currently favour endoscopic removal of the bile duct stones followed by an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Others reserve endoscopic removal for patients in whom laparoscopic clearance of the common bile duct has been unsuccessful.

The Postsurgical and Critically Ill Jaundiced Patient

The evaluation of a postsurgical patient with jaundice can be challenging. The cause is often multifactorial and may include increased bilirubin production from reabsorption of a haematoma, impaired hepatocellular function from decreased blood flow, total parental nutrition (TPN), sepsis and occasionally extrahepatic biliary obstruction (Table 23.4). Therefore, information on the pattern of development, review of the operative and anaesthesia reports, pre- and postoperative drug use, haemodynamic changes and fluid management, and any history of hypovolaemia or hypotension are required.

Table 23.4 Distinguishing features that help to determine the cause of postoperative jaundice

| Aetiology | Feature |

|---|---|

| Hypotension | ALT > 1000 U/L, LDH elevated |

| Drugs, e.g. halothane | None |

| Infection | Increased white cell count, fever |

| TPN | Liver function test profiles rise 1–4 weeks after TPN commencement. |

| Haematoma resorption | ↑ unconjugated bilirubin |

| Cardiac failure | Elevated jugular venous pressure, enlarged pulsatile liver |

| Haemolysis | ↑ unconjugated bilirubin, ↑ LDH, ↓ haptoglobin, abnormal blood smear |

| Renal failure | ↑ creatinine |

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; TPN = total parenteral nutrition.

TPN causes many liver abnormalities including fatty liver, cholestasis, portal inflammation, gallstone formation and occasionally steatohepatitis and cirrhosis (Ch 17). Liver function abnormalities usually occur 1–4 weeks after the initiation of TPN and resolve on discontinuing therapy. Transaminase levels can become elevated within 1 week, and alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase levels often begin to rise after 3–4 weeks. Increases in serum bilirubin levels can occur but are unusual. The causes are commonly multifactorial. The transaminase rise is most likely due to glucose intolerance, while cholestasis is considered to be the result of abnormal lipid metabolism. Often small adjustments in TPN composition can correct the liver dysfunction and discontinuing the TPN usually leads to regression of dysfunction.

The Immunocompromised Patient who is Jaundiced

Patients who are immunocompromised by infection with HIV or who are receiving immunosuppressive therapy may develop hepatobiliary infections not usually found in the immunocompetent patient. Biliary tract infections can produce marked jaundice and right upper quadrant pain. Other causes of jaundice include neoplasms and drug reactions (see Table 23.5).

Table 23.5 Common causes of jaundice in immunosuppressed patients

| Aetiology | Examples |

|---|---|

| Hepatitis: infectious | Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, tuberculosis, cytomegalovirus |

| Hepatitis: drugs | lsoniazid, AZT, sulfonamides |

| AIDS cholangiopathy | Cytomegalovirus, Cryptosporidium spp. |

| Veno-occlusive disease | Antineoplastic drugs (e.g. busulfan) |

| Neoplasm | Lymphoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma |

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

The most common causes of hepatocellular disease, in decreasing order, are Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, drugs, cytomegalovirus, bacillary peliosis hepatis, lymphoma and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Kaposi’s sarcoma, hepatitis C and B and cryptococcal infection are other causes of jaundice. Drugs such as sulfonamides, isoniazid, phenytoin and azidothymidine (AZT) may cause cholestatic jaundice.

Key Points

Clayton E.S., Connor S., Alexakis N., et al. Meta-analysis of endoscopy and surgery versus surgery alone for common bile duct stones with the gallbladder in situ. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1185-1191.

Hiramanek N. Itch: a symptom of occult disease. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33(7):495-499.

Kocher M., Cerna M., Havlik R., et al. Percutaneous treatment of benign bile duct strictures. Eur J Radiol. 2007;62:170-174.

Petrov M.S., Savides T.J. Systematic review of endoscopic ultrasonography versus endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for suspected choledocholithiasis. Br J Surg. 2009;96:967-974.

Radhakrishnan J., Uppot R.N., Colvin R.B. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 5–2010. A 51-year-old man with HIV infection, proteinuria, and edema. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):636-646.

Vassilou M.C., Laycock W.S. Bilary dyskinesia. Surg Clin N Am. 2008;88:1253.

Wamsteker E.J. Updates in biliary endoscopy 2006. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23(3):324-328.