Chapter 4 Isolated Congenital Complete Heart Block

Congenital complete atrioventricular block was recognized in 1901 when Morquio1 described familial recurrence with Stokes-Adams attacks and death in childhood. In 1908, van den Heuvel2 published the electrocardiogram of a patient with complete heart block and syncopal episodes that dated from infancy. Thirteen years later, White and Eustis3 described slow fetal heart rate; at birth, the electrocardiogram disclosed complete heart block.3 Davis and Stecher4 distinguished congenital from acquired complete heart block; shortly thereafter, Yater5–7 established criteria for the clinical diagnosis of the congenital form. Currently, complete atrioventricular block is regarded as congenital when it is diagnosed in utero, at birth, or within the neonatal period.8

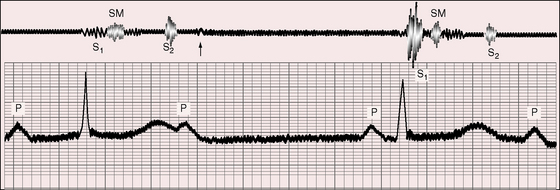

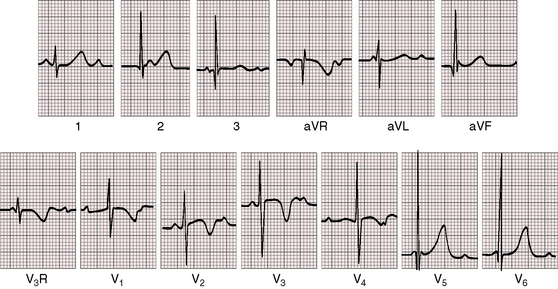

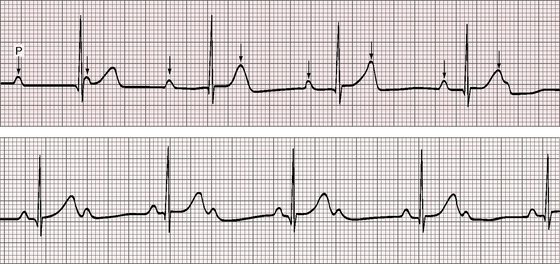

Complete heart block is characterized by a random relationship between atrial and ventricular activation. Atrial impulses are not conducted to the ventricles, which are depolarized in response to a subsidiary pacemaker.9 The electrocardiogram is a simple but secure means of identifying complete heart block (Figures 4-1 and 4-2). Atrioventricular dissociation is a disorder of both conduction and impulse formation9 and is not considered in this chapter.

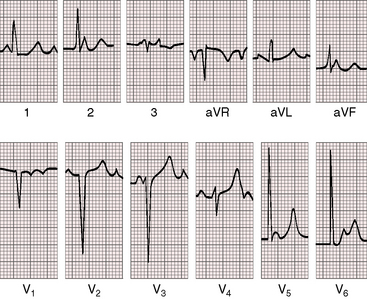

Figure 4-1 Electrocardiogram from a 7-year-old boy with isolated congenital complete heart block. P waves are independent of QRS complexes. The QRS complex is normal in configuration and duration, and its axis is normal. Deep Q waves and tall R waves are found in leads V5 and V6. The R wave in lead V1 is relatively tall, with an R/S ratio of 1:1. T waves are deeply inverted in right precordial leads and are tall and peaked in left precordial leads. See Figure 4-5 for rhythm strip.

Fetal echocardiography permits intrauterine diagnosis, and isolated complete heart block can be distinguished from cases with coexisting congenital heart disease, most commonly ventricular inversion (see Chapter 6) and left isomerism (see Chapter 3). The incidence rate of congenital high-degree heart block, either complete or with more than 50% of blocked atrial impulses, has been estimated at 1 in 2500 to 1 in 20,000 live births.9–12 Block can be within the atrioventricular (AV) node or within the His bundle (or infra-Hisian), and the discontinuity in conduction can be anatomic or functional.13,14 Narrow QRS complexes indicate that the subsidiary pacemaker is above the bifurcation of the His bundle,9 but morphologic abnormalities have been identified at multiple levels.7,13,15,16 The connection between atrial muscle and atrioventricular node is deficient or absent.13,16 The node can be congenitally absent or defective13,14,16,17 and separated from the His bundle,18 which supports the view that the AV node and bundle of His originate as separate structures that normally are destined to join during early fetal development.15 Disruption can be within the His bundle,13,19 at the origins of the bundle branches, or in the right or left bundle branch.16 Anatomic defects occasionally exist in the AV node itself or at the junction of AV node and atrial muscle.15 The fetal sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes can calcify.20 Nevertheless, spontaneous changes from complete to incomplete heart block21,22 or even to sinus rhythm23,24 indicate that interruption of the conduction pathways is not necessarily anatomic, complete, or permanent (Figure 4-3).

Myocardial contractile force is augmented by the slow heart rate, the long diastolic filling period, and the increased end-diastolic volume and fiber length,9,25 so stroke volume increases and basal cardiac output is maintained.26,27 An increase in cardiac output with exercise is chiefly rate dependent.26 Submaximal isotonic exercise generally provokes an appropriate increase in ventricular rate and cardiac output, but higher workloads are accompanied by blunted hemodynamic and rate responses.26 An increase in stroke volume and, to a lesser degree, an increase in arteriovenous oxygen difference partially compensate for the blunted rate response.25 Despite compensatory mechanisms, oxygen consumption during submaximal exercise is significantly lower than in healthy age-matched and sex-matched control subjects.25 A subset of patients with congenital complete heart block has development of dilated cardiomyopathy for which no definite cause has been found.28

An association between maternal lupus erythematosus and congenital complete heart block was reported in 1966 and confirmed a decade later.9,29–32 Congenital heart block is a passively transferred autoimmune disease that affects the offspring of mothers with Ro/SSA autoantibodies.33 Sinus node disease may occur in children with prenatal exposure to anti-Ro or anti-La antibodies.34 Complete heart block in utero or at birth is strongly associated with the neonatal lupus syndrome and with maternal antibodies to 48-kD SSB/La, 52-kD SSA/Ro, and 60-kD SSA/Ro ribonucleoproteins.35 Congenital heart block is an important model of passive autoimmunity, with cardiac injury believed to be in response to active transport of maternal immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies into the fetal circulation.35 Anti-SSA/Ro associated with third-degree heart block is irreversible.36 Dilation of the ascending aorta is present in a large proportion of pediatric patients with isolated congenital complete heart block.37

History

Congenital complete heart block necessarily begins in utero10,38 and must be distinguished from the bradycardia of fetal distress,39,40 a distinction that is more certain when the slow heart rate is detected before the onset of labor.40 However, congenital complete heart block usually comes to attention because an inappropriately slow heart rate is detected in an otherwise healthy neonate or infant (see subsequent section, Arterial Pulse).

Fetal echocardiography is used to establish the diagnosis and determine whether the heart block is isolated or associated with congenital heart disease, which is usually left isomerism or ventricular inversion (see previous discussion). Only 14% of fetuses with coexisting congenital heart disease survive as neonates.10 Conversely, 85% of fetuses with isolated intrauterine complete heart block live beyond the neonatal period.10,26,38 This survival rate is similar to that of isolated congenital complete heart block diagnosed after birth, in which approximately 90% of infants and children are alive at long-term follow-up.10 The fetal cardiac rhythm may change from sinus to second-degree atrioventricular block to complete heart block within hours or weeks after birth, which suggests that immunologic damage occurs early, develops slowly, or appears late.10

A tendency for female preponderance in congenital complete heart block has been found,41 and approximately 76% of mothers of affected children are white.35 Familial heart block has been well established.9,22,39,42–45 In Morquio’s1 original description, atrioventricular block recurred in five of eight siblings (see previous mention). Osler46 reported Stokes-Adams attacks in a patient who had relatives with slow pulses. Familial congenital heart block can become overt years after birth43,47 and can be characterized by right or left bundle branch block.48 Almost all degrees and forms of heart block have occurred in different members of the same family. Four generations of a single family had right bundle branch block, left anterior fascicular block, bifascicular block, and complete heart block.49 Mothers with systemic lupus erythematosus and one child with neonatal heart block are at greater risk of having subsequent offspring with heart block.45 Children of mothers with lupus not only can have congenital heart block but subsequently can have development of the overt connective tissue disease.50 Maternal lupus may not become manifest for years after birth of an infant with congenital complete heart block.51 Long-term outlook for the mothers is more reassuring, however.52,53

The key determinants of clinical stability in isolated congenital complete heart block are the ventricular rate, the hemodynamic adjustments at rest and with exercise (previously discussed), and the presence of inherently normal myocardium.9,54 Nevertheless, patients can have development of dilated cardiomyopathy attributed to bradycardia, and a strong relationship exists between SSA/Ro and SSB/La antibodies and cardiomyopathy.28,52 Although subnormal exercise performance has been reported in children and adolescents with congenital complete atrioventricular block,23,55,56 exercise tolerance is generally normal or nearly so, and endurance performance is occasionally normal.25,57 One patient was an ardent ice hockey player, and other patients have included Air Force pilots,58,59 a cricket player,55 a 56-year-old woman who for 20 years walked 2 miles to her daily job on a farm,24 a 38-year-old man who had won boxing matches in his youth,24 and a 48-year-old man who experienced a normal response to a Royal Canadian Air Force decompression chamber at age 23 years and subsequently flew jet aircraft.54 High levels of physical activity are not desirable but are at least possible despite the exercise limitations described previously. Pregnancy is generally uneventful in otherwise healthy women with congenital heart block,60,61 but Stokes-Adams attacks occasionally occur during gestation or the puerperium.61

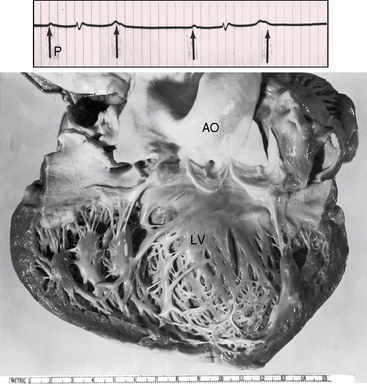

A substantial majority of young patients with isolated congenital complete heart block are asymptomatic, but the mortality rate even in infancy and childhood is estimated at 8%,62 and longevity in adolescents and adults is less than normal.23,41,62 The heart may not respond adequately to increased circulatory demands, especially in the vulnerable neonatal period.9,41,54,62 Infants with slow ventricular rates may succumb to congestive heart failure before physiologic adaptation is achieved.62 Metabolic acidosis slows the heart rate,63 and the stress of febrile illnesses in infancy are poorly tolerated. Congenital complete heart block may come to light in toddlers because of night terrors or irritability.9 Stokes-Adams episodes are uncommon in the young but pose tangible hazards, with symptoms that range from mild dizziness to syncope and convulsions.24,55 Neurologic sequelae follow cardiac arrest. A Stokes-Adams episode with sudden death can occur in previously asymptomatic patients (Figure 4-4). Fatal Stokes-Adams seizures occasionally occur in childhood, but death rarely accompanies the initial episode.23,41 One patient experienced recurrent Stokes-Adams episodes between 2 and 4 years of age, but the attacks gradually diminished and finally vanished, leaving him able to participate in cricket, football, and swimming.23,55 Syncope and sudden death are usually caused by bradycardia, but ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation also play a role.25 Frequent ventricular ectopic beats have been recorded during nocturnal monitoring, and young patients sometimes experience unifocal, multifocal, or repetitive ventricular ectopic beats during treadmill exercise.57 Serious symptoms and complications are more likely in patients with daytime heart rates below 50 beats per minute, wide QRS complexes, a blunted rate response to graded exercise, a disproportionate increase in left ventricular internal dimensions, or subnormal left ventricular function.64

Arterial pulse

A pulse rate inappropriately slow for age often leads to the diagnosis of congenital complete heart block. At birth, the heart rate in affected patients is seldom more than 90 beats per minute, and in infants, the rate is seldom more than 65 to 70 beats per minute.9 After infancy, the basal rate generally exceeds 50 beats per minute (Figure 4-5) and not uncommonly reaches 60, 70, or even 80 beats per minute.23 The pulse rate in congenital complete heart block is slow but is relatively rapid compared with acquired complete heart block.23,24 In healthy young adults, rates of 40 to 60 beats per minute may be mistaken for sinus bradycardia.23 A Royal Canadian Air Force veteran described by Mathewson and Harvie58 was a case in point. His slow heart rate was initially attributed to the sinus bradycardia of physical conditioning. Strenuous exercise was tolerated without difficulty. Complete heart block thought to be congenital was subsequently recognized.

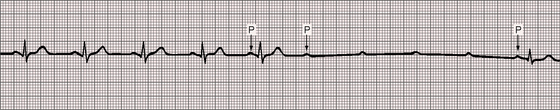

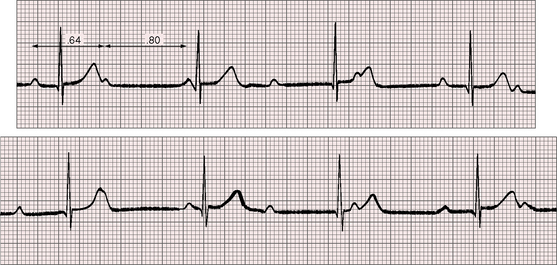

Figure 4-5 Long strip of lead 2 of the electrocardiogram shown in Figure 4-1. Independent P waves are identified with arrows. The PP intervals are shorter when separated by a QRS complex (positive chronotropic effect). The ventricular rate is 48 to 50 beats per minute. The QRS complexes are narrow.

Three features other than rate deserve comment: namely, upstroke, pulse pressure, and atrial waves. The upstroke is brisk, and the pulse pressure is relatively wide.55 Rapid ejection of a large stroke volume from a functionally normal left ventricle increases the rate of rise and increases the systolic pressure, while prolonged diastole permits a pressure decline to relatively low levels. Small waves synchronous with atrial contraction appear on the diastolic portion of the arterial pressure pulse65 and can sometimes be detected with meticulous palpation. These waves are believed to result from external impact of the left atrium on the aorta and are analogous to waves that have been recorded on the pulmonary arterial pressure pulse. Sinus arrhythmia is conspicuous by its absence and weighs in favor of sinus bradycardia.

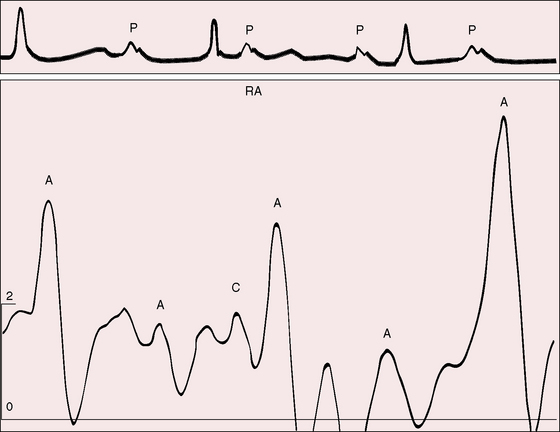

Jugular venous pulse

The jugular venous pulse alone is a reliable indication of complete heart block. Independent A waves occur at a rate more rapid than the arterial pulse and intermittently increase in amplitude (see subsequent discussion). Small regular A waves during diastole occur more rapidly than the arterial pulse rate, which indicates that atrial and ventricular contractions are independent. When the right atrium contracts against a tricuspid valve that has been fortuitously closed during a ventricular systole, the A wave abruptly amplifies—a cannon wave (Figure 4-6).66 Precise timing of cannon waves localizes their maximal amplitude at isovolumetric ventricular systole.67 The first heart sound that accompanies a cannon wave is comparatively soft because atrial systole follows rather than precedes ventricular contraction (see subsequent discussion).

Auscultation

Auscultation is a means of suspecting fetal complete heart block.40 Intrauterine diagnosis was made in a twin when two fetal heart rates were detected, one at 52 beats per minute and the other at 150 beats per minute.40

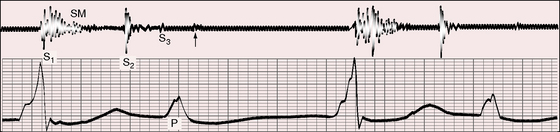

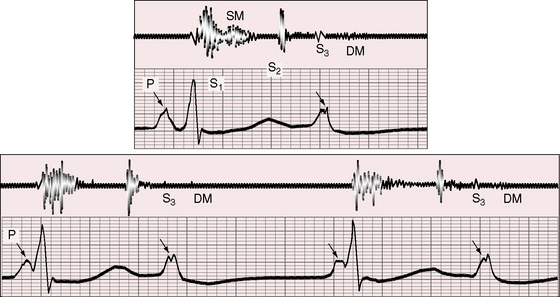

The following auscultatory signs are useful in the diagnosis of congenital complete heart block: (1) variable intensity of the first heart sound; (2) a midsystolic murmur; (3) normal respiratory splitting of the second heart sound; (4) a third heart sound; (5) a fourth heart sound; (6) a summation sound; (7) an atrial murmur; (8) a mid-diastolic murmur; and (9) vascular sounds over the carotid, subclavian, and femoral arteries. Variation in intensity of the first heart sound is an auscultatory hallmark of complete heart block (Figures 4-7 through 4-10).66,68 When the variation occurs with a slow heart rate and a regular rhythm, the diagnosis of complete heart block can be entertained with considerable confidence.

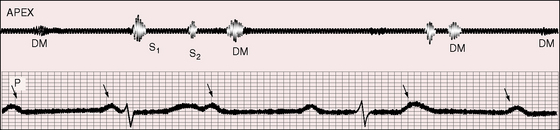

Figure 4-7 Phonocardiogram (apex) and electrocardiogram (lead 2) from the 25-year-old man referred to in Figure 4-2. The first heart sound (S1) is loud and constant because each QRS complex is immediately preceded by a P wave, to which it is fused. The independent P waves are tall and notched. A grade 2/6 systolic murmur (SM), a third heart sound (S3), and a short, soft diastolic murmur (arrow) follow the independent P waves.

Figure 4-8 Phonocardiogram (cardiac apex) and electrocardiogram (lead 2) from the 25-year-old man whose 12-lead tracing is shown in Figure 4-2. The first heart sound (S1) is loud (short interval between P wave and QRS complex). A grade 2/6 to 3/6 systolic murmur (SM) ends well before the second heart sound (S2). The murmur was maximal at the mid left sternal border. A third heart sound (S3) and a short diastolic murmur (DM) follow the subsequent P wave, which is notched.

The PR relationship is an important determinant of the intensity of the first heart sound, an observation made by Wolferth and Margolies in 1930.69 In complete heart block, the PR relationship changes from beat to beat because the atria and ventricles contract independently, so the first sound varies in intensity from cycle to cycle, ranging from booming (bruit de canon) to virtual inaudibility (see Figures 4-7, 4-9, and 4-10). The first heart sound is loud when the PR interval is short (120 msec or less), soft when the PR interval is long (200 to 300 msec), and louder again when PR prolongation exceeds 500 msec.66,68 When the PR interval exceeds 500 msec, reopening of the mitral valve is followed by secondary closure at the onset of ventricular systole, resulting in reappearance of the first heart sound.68

A grade 2/6 to 3/6 midsystolic murmur is related principally if not exclusively to rapid ejection of a large stroke volume from the right ventricle (see Figures 4-7, 4-8, and 4-9). Maximal intensity is at the mid to upper left sternal border. The murmur is relatively short, occupying the first half to two thirds of systole and always ending well before the second heart sound.66

Normal respiratory splitting of the second heart sound is a useful sign of congenital as opposed to acquired complete heart block.66 Physiologic splitting implies a normal sequence of ventricular activation that is in accord with a narrow QRS complex and a subsidiary pacemaker above the bifurcation of the His bundle (see subsequent section, Electrocardiogram).

Third heart sounds are indistinguishable from normal third heart sounds in the young (see Figures 4-7 and 4-8). However, fourth heart sounds—aptly called gallop du bloc by Gallavardin70—are of special interest because they are not heard in healthy young people. Timing in diastole is variable because the atria and ventricles beat independently. The fourth sounds have the brevity of a sound per se (see Figure 4-9) or the prolongation of a short murmur (see Figure 4-8). When atrial contraction coincides with rapid ventricular filling, third and fourth heart sounds either summate or generate a short mid-diastolic murmur (see Figure 4-10). Summation sounds and mid-diastolic murmurs are detected more often than isolated fourth heart sounds or atrial murmurs. Systolic vascular sounds attributed to high-velocity ejection are occasionally heard over the carotid, subclavian, and femoral arteries.

Electrocardiogram

The definitive diagnosis of complete heart block depends on nothing more than an electrocardiogram. Fetal electrocardiography is an extension of this simple accurate diagnostic tool.40

The P wave of atrial activity and the QRS of ventricular activity occur independently, with no arithmetical relationship between the two (see Figure 4-5). In acquired complete heart block, periods of synchronization—accrochage—sometimes occur.16,71 This phenomenon is seldom witnessed in congenital complete heart block (see Figure 4-7). Although atrial depolarization does not activate the ventricles, examples of a change from partial to complete heart block,21 as well as from complete to partial heart block, are occasionally encountered (see Figure 4-3).23,24 A neonate with congenital complete heart block experienced intermittent 1/1 atrioventricular conduction through a Wolff-Parkinson-White accessory pathway.53

The atrial rate tends to decrease with age but remains rapid compared with the ventricular rate, which is relatively constant after infancy until well into adulthood.23,24 During exercise, a stepwise increase is seen in atrial rate with slow return to normal, whereas the ventricular rate increases irregularly with a more rapid return to baseline levels. The flat exercise response of the subsidiary junctional pacemaker56 was mentioned previously. Rarely, atrial flutter coexists with congenital complete heart block.72

The PP intervals vary in both congenital and acquired complete heart block. PP intervals that are separated by a QRS complex tend to be shorter (positive chronotropic effect) and less commonly longer (negative chronotropic effect) than PP intervals that are not separated by a QRS (Figure 4-11).

Figure 4-11 Rhythm strips of lead 2 of the electrocardiogram shown in Figure 4-1. The P waves are independent, and the ventricular rate is 47 beats per minute. The first PP interval is separated by a QRS complex and is relatively short (0.64 second; positive chronotropic effect). The second PP interval is not separated by a QRS complex and is relatively long (0.80 second).

Sinus P waves are tall and broad, reflecting volume overload of the atria (see Figures 4-4, 4-7, and 4-8). A normal QRS duration indicates a normal sequence of ventricular activation because the pacemaker is located above the bifurcation of the His bundle (see Figures 4-1 and 4-2).24 In acquired complete heart block, the QRS duration is prolonged because the idioventricular pacemaker is located below the His bundle and its major branches. In congenital complete heart block, the QRS occasionally resembles right or left bundle branch block because the block is infra-Hisian. The lower the pacemaker is in the conduction system, the greater the vulnerability to Stokes-Adams syncope. When QRS prolongation coincides with a slow heart rate, Stokes-Adams attacks are more likely.

In familial complete heart block with adult onset, the QRS duration is prolonged and the outlook is unfavorable.44 Ambulatory electrocardiograms of isolated congenital complete heart block have recorded multiple arrhythmias: junctional exit block, exercise-related ventricular ectopic beats, blunted ventricular rate responses, and marked nocturnal bradycardia.56,57,73

Voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy are sometimes present, together with prominent left precordial Q waves of volume overload (see Figures 4-1 and 4-2). Right ventricular hypertrophy or biventricular hypertrophy is occasional.

The T wave configuration is likely to be normal, but deep T wave inversions or coving sometimes occur in right or midprecordial leads, and T waves may be peaked in left chest leads (see Figures 4-1 and 4-2). QT interval prolongation increases the risk of torsades de pointes.74

His bundle electrograms in congenital complete heart block are used to identify the location of the conduction defect and the site of the subsidiary pacemaker (see previous discussion).62,75–78 The block is typically proximal to the site at which His bundle potentials are recorded.77–79 A normal HV interval and a normal QRS complex indicate that the conduction system is normal distal to the site of block.78 His electrograms do not permit identification of where in the AV junction the escape rhythm originates because block proximal to the His potential can be within the AV node, between the AV node and atrial muscle, or in the AV node–His bundle junction.13,77,78

Escape rhythms in congenital complete heart block are likely to originate in the bundle of His because automaticity is a property of His/Purkinje cells but not of AV nodal cells. Origin is probably in the proximal His bundle in light of observations on complete heart block from intra-His discontinuity.76,78 Electrophysiologic studies have recorded split His potentials proximal and distal to the site of block,76 so the escape pacemaker can be in the distal His bundle at the site of the second His potential. The distal pacemaker is associated with a slower ventricular rate and little or no acceleration in response to atropine.

X-ray

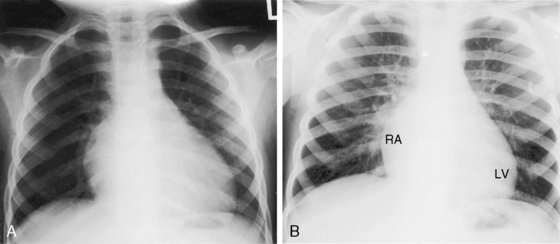

The radiologic appearances of the heart, great arteries, and lungs tend to be normal in congenital complete heart block.24 Ventricular chamber size usually remains constant through adulthood.23 A mild to moderate increase in heart size reflects prolonged diastolic filling periods and increased ventricular volume because of the slow heart rate (Figures 4-4 and 4-12).80

Figure 4-12 X-rays from the child whose electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 4-1. A, At age 4 years, the heart size was a moderately increased (LV = left ventricle; RA = right atrium). B, At age 7 years, a further increase in heart size coincided with a decrease in heart rate to 50 beats per minute.

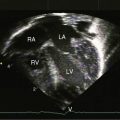

Echocardiogram

Echocardiography with Doppler interrogation and color flow imaging are used to establish that the congenital complete heart block is isolated,64 and fetal echocardiography is used to establish the diagnosis of isolated intrauterine complete heart block. Complete heart block can be diagnosed in utero with pulsed Doppler and color flow recordings of left ventricular inflow and outflow signals.10,38,81,82

1 Morquio L. Sur une maladie infantile et familiale caractérisée par des modifications permanentes du pouls, des attaques syncopales et epileptiforme et la mort subite. Archives médicales d’enfants. 1901;4:467.

2 Van den Heuvel G. De zeikte van Stokes-Adams eneen geval van aangeborenen hartblock. Groningen Proefschrift Rijks Universitait. 1908;12:142.

3 White P., Eustis R. Congenital heart block. Am J Dis Child. 1921;22:299.

4 Davis H., Stecher R. Congenital heart block. Am J Dis Child. 1928;36:115.

5 Yater W. Congenital heart block; review of the literature; report of case with incomplete heterotaxy; electrocardiogram in dextrocardia. Am J Dis Child. 1929;38:112.

6 Yater W., Leamon W., Cornall V. Congenital heart block; report of third case of complete heart block studied by serial section through conduction system. J Am Med Assoc. 1934;102:1660.

7 Yater W., Lyon J., Mcnabb P. Congenital heart block; review and report of second case of complete heart block studied by serial sections through conduction system. J Am Med Assoc. 1933;100:1831.

8 Brucato A., Jonzon A., Friedman D., et al. Proposal for a new definition of congenital complete atrioventricular block. Lupus. 2003;12:427-435.

9 Ross B.A. Congenital complete atrioventricular block. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1990;37:69-78.

10 Schmidt K.G., Ulmer H.E., Silverman N.H., Kleinman C.S., Copel J.A. Perinatal outcome of fetal complete atrioventricular block: a multicenter experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1360-1366.

11 Anderson R.H., Wenick A.C., Losekoot T.G., Becker A.E. Congenitally complete heart block. Developmental aspects. Circulation. 1977;56:90-101.

12 Suarez-Penaranda J.M., Munoz J.I., Rodriguez-Calvo M.S., Ortiz-Rey J.A., Concheiro L. The pathology of the heart conduction system in congenital heart block. J Clin Forensic Med. 2006;13:341-343.

13 Bharati S., Lev M. Pathology of atrioventricular block. Cardiol Clin. 1984;2:741-751.

14 Lev M. The normal anatomy of the conduction system in man and its pathology in atrioventricular block. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1964;111:817-829.

15 James T.N. Cardiac conduction system: fetal and postnatal development. Am J Cardiol. 1970;25:213-226.

16 Lev M., Silverman J., Fitzmaurice F.M., Paul M.H., Cassels D.E., Miller R.A. Lack of connection between the atria and the more peripheral conduction system in congenital atrioventricular block. Am J Cardiol. 1971;27:481-490.

17 Lev M., Benjamin J.E., White P.D. A histopathologic study of the conduction system in a case of complete heart block of 42 years’ duration. Am Heart J. 1958;55:198-214.

18 Lev M. The anatomic basis for disturbances in conduction and cardiac arrhythmias. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1960;2:360-369.

19 Lev M., Cuadros H., Paul M.H. Interruption of the atrioventricular bundle with congenital atrioventricular block. Circulation. 1971;43:703-710.

20 Angelini A., Moreolo G.S., Ruffatti A., Milanesi O., Thiene G. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Calcification of the atrioventricular node in a fetus affected by congenital complete heart block. Circulation. 2002;105:1254-1255.

21 Dunn H.G. Congenital partial heart block. Proc R Soc Med. 1952;45:456-458.

22 Khorsandian R.S., Moghadam A.N., Mueller O.F. Familial congenital A-V dissociation. Am J Cardiol. 1964;14:118-124.

23 Campbell M., Emanuel R. Six cases of congenital complete heart block followed for 34-40 years. Br Heart J. 1967;29:577-587.

24 Campbell M., Thorne M.G. Congenital heart block. Br Heart J. 1956;18:90-101.

25 Reybrouck T., Vanden Eynde B., Dumoulin M., Van Der Hauwaert L.G. Cardiorespiratory response to exercise in congenital complete atrioventricular block. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:896-899.

26 Manno B.V., Hakki A.H., Eshaghpour E., Iskandrian A.S. Left ventricular function at rest and during exercise in congenital complete heart block: a radionuclide angiographic evaluation. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:92-94.

27 Thilenius O.G., Chiemmongkoltip P., Cassels D.E., Arcilla R.A. Hemodynamics studies in children with congenital atrioventricular block. Am J Cardiol. 1972;30:13-18.

28 Udink Ten Cate F.E., Breur J.M., Cohen M.I., et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy in isolated congenital complete atrioventricular block: early and long-term risk in children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1129-1134.

29 Chameides L., Truex R.C., Vetter V., Rashkind W.J., Galioto F.M.Jr, Noonan J.A. Association of maternal systemic lupus erythematosus with congenital complete heart block. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1204-1207.

30 Litsey S.E., Noonan J.A., O’Connor W.N., Cottrill C.M., Mitchell B. Maternal connective tissue disease and congenital heart block. Demonstration of immunoglobulin in cardiac tissue. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:98-100.

31 Mccue C.M., Mantakas M.E., Tingelstad J.B., Ruddy S. Congenital heart block in newborns of mothers with connective tissue disease. Circulation. 1977;56:82-90.

32 Nolan R.J., Shulman S.T., Victorica B.E. Congenital complete heart block associated with maternal mixed connective tissue disease. J Pediatr. 1979;95:420-422.

33 Ottosson L., Salomonsson S., Hennig J., et al. Structurally derived mutations define congenital heart block-related epitopes within the 200-239 amino acid stretch of the Ro52 protein. Scand J Immunol. 2005;61:109-118.

34 Menon A., Silverman E.D., Gow R.M., Hamilton R.M. Chronotropic competence of the sinus node in congenital complete heart block. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1119-1121. A1119

35 Buyon J.P., Hiebert R., Copel J., et al. Autoimmune-associated congenital heart block: demographics, mortality, morbidity and recurrence rates obtained from a national neonatal lupus registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1658-1666.

36 Friedman D.M., Kim M.Y., Copel J.A., et al. Utility of cardiac monitoring in fetuses at risk for congenital heart block: the PR Interval and Dexamethasone Evaluation (PRIDE) prospective study. Circulation. 2008;117:485-493.

37 Radbill A.E., Brown D.W., Lacro R.V., et al. Ascending aortic dilation in patients with congenital complete heart block. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1704-1708.

38 Gembruch U., Hansmann M., Redel D.A., Bald R., Knopfle G. Fetal complete heart block: antenatal diagnosis, significance and management. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1989;31:9-22.

39 Connor A.C., McFadden J.F., Houston B.J., Finn J.L. Familial congenital complete heart block; case report and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78:75-79.

40 Dunn H.P. Antenatal diagnosis of congenital heart block. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Empire. 1960;67:1006-1007.

41 Reid J.M., Coleman E.N., Doig W. Complete congenital heart block. Report of 35 cases. Br Heart J. 1982;48:236-239.

42 Gazes P.C., Culler R.M., Taber E., Kelly T.E. Congenital familial cardiac conduction defects. Circulation. 1965;32:32-34.

43 Morgans C.M., Gray K.E., Robb G.H. A survey of familial heart block. Br Heart J. 1974;36:693-696.

44 Sarachek N.S., Leonard J.L. Familial heart block and sinus bradycardia. Classification and natural history. Am J Cardiol. 1972;29:451-458.

45 Scheib J.S., Waxman J. Congenital heart block in successive pregnancies: a case report and evaluation of risk with therapeutic consideration. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:481-484.

46 Osler W. On the so-called Stokes-Adams disease. Lancet. 1903;2:516.

47 James T.N., Spencer M.S., Kloepfer J.C. De Subitaneis Mortibus. XXI. Adult onset syncope. with comments on the nature of congenital heart block and the morphogenesis of the human atrioventricular septal junction. Circulation. 1976;54:1001-1009.

48 Esscher E., Hardell L.I., Michaelsson M. Familial, isolated, complete right bundle-branch block. Br Heart J. 1975;37:745-747.

49 Stephan E. Hereditary bundle branch system defect: survey of a family with four affected generations. Am Heart J. 1978;95:89-95.

50 Lanham J.G., Walport M.J., Hughes G.R. Congenital heart block and familial connective tissue disease. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:823-825.

51 Kasinath B.S., Katz A.I. Delayed maternal lupus after delivery of offspring with congenital heart block. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:2317.

52 Eronen M. Long-term outcome of children with complete heart block diagnosed after the newborn period. Pediatr Cardiol. 2001;22:133-137.

53 Mcleod K.A., Rankin A.C., Houston A.B. 1:1 atrioventricular conduction in congenital complete heart block. Heart. 1998;80:525-526.

54 Corne R.A., Mathewson F.A. Congenital complete atrioventricular heart block. A 25 year follow-up study. Am J Cardiol. 1972;29:412-415.

55 Campbell M. Congenital complete heart block. Br Heart J. 1943;5:15-18.

56 Dewey R.C., Capeless M.A., Levy A.M. Use of ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring to identify high-risk patients with congenital complete heart block. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:835-839.

57 Winkler R.B., Freed M.D., Nadas A.S. Exercise-induced ventricular ectopy in children and young adults with complete heart block. Am Heart J. 1980;99:87-92.

58 Mathewson F.A., Harvie F.H. Complete heart block in an experienced pilot. Br Heart J. 1957;19:253-258.

59 Turner L.B. Asymptomatic congenital complete heart block in an Army Air Force pilot. Am Heart J. 1947;34:426-431.

60 Groves A.M., Allan L.D., Rosenthal E. Outcome of isolated congenital complete heart block diagnosed in utero. Heart. 1996;75:190-194.

61 Perloff J. Pregnancy and congenital heart disease. In Perloff J., Child J., Aboulhosn J., editors: Congenital heart disease in adults, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2009.

62 Michaelsson M., Engle M.A. Congenital complete heart block: an international study of the natural history. Cardiovasc Clin. 1972;4:85-101.

63 Spach M.S., Scarpelli E.M. Circulatory dynamics and the effects of respiration during ventricular asystole in dogs with complete heart block. Circ Res. 1962;10:197-207.

64 Sholler G.F., Walsh E.P. Congenital complete heart block in patients without anatomic cardiac defects. Am Heart J. 1989;118:1193-1198.

65 Howarth S. Atrial waves on arterial pressure records in normal rhythm, heart block, and auricular flutter. Br Heart J. 1954;16:171-176.

66 Perloff J. Physical examination of the heart and circulation, 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2009.

67 Lagerlof H., Werko L. Studies on circulation in man: auricular pressure pulse. Cardiologia. 1948;13:240.

68 Burggraf G.W., Craige E. The first heart sound in complete heart block. Phono-echocardiographic correlations. Circulation. 1974;50:17-24.

69 Wolferth C.C., Margolies A. The influence of auricular contraction on the first heart sound and the radial pulse. Arch Intern Med. 1930;46:1048-1071.

70 Gallavardin L. Contractions auriculaires perceptibles à l’oreille dans le bloc total. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1914;7:171.

71 Marriott H.J. Atrioventricular synchronization and accrochage. Circulation. 1956;14:38-43.

72 Schuster B., Imm C.W. Congenital atrial flutter with complete heart block. Am J Cardiol. 1963;12:575-578.

73 Nagashima M., Nakashima T., Asai T., et al. Study on congenital complete heart block in children by 24-hour ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring. Jpn Heart J. 1987;28:323-332.

74 Kernohan R.J., Froggatt P. Atrioventricular dissociation with prolonged QT interval and syncopal attacks in a 10-year-old boy. Br Heart J. 1974;36:516-519.

75 Abella J.B., Teixeira O.H., Misra K.P., Hastreiter A.R. Changes of atrioventricular conduction with age in infants and children. Am J Cardiol. 1972;30:876-883.

76 Bharati S., Lev M., Wu D., Denes P., Dhingra R., Rosen K.M. Pathophysiologic correlations in two cases of split His bundle potentials. Circulation. 1974;49:615-623.

77 Kelly D.T., Brodsky S.J., Mirowsri M., Krovetz J., Rowe R.D. Bundle of His recordings in congenital complete heart block. Circulation. 1972;45:277-281.

78 Rosen K.M., Mehta A., Rahimtoola S.H., Miller R.A. Sites of congenital and surgical heart block as defined by His bundle electrocardiography. Circulation. 1971;44:833-841.

79 Smithen C.S., Sowton E. His bundle electrograms. Br Heart J. 1971;33:633-638.

80 Moss A.J. Congenital complete atrioventricular block. Clinical features, hemodynamic findings, and physical working capacity. Lancet. 1961;81:542-547.

81 Arbeille P., Paillet C., Chantepie B. In utero ultrasonic diagnosis of atrioventricular block. J Cardiovasc Ultrasonogr. 1984;3:313.

82 Kleinman C.S., Hobbins J.C., Jaffe C.C., Lynch D.C., Talner N.S. Echocardiographic studies of the human fetus: prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease and cardiac dysrhythmias. Pediatrics. 1980;65:1059-1067.