Chapter 10 Iron Dysregulation in Restless Legs Syndrome

In the 1940s and 1950s, while Ekbom1,2 was proposing a vascular model for restless legs syndrome (RLS), Nordlander3 was establishing a role for iron in RLS. He noted that his patients with RLS had a high prevalence of iron deficiency and that their symptoms improved on treatment of the iron deficiency. In 1953, Nordlander formally proposed “that restless legs might … be a sign of iron deficiency.”3 Ekbom acknowledged Nordlander’s finding and reported a 24.6% prevalence of iron deficiency among his patient population.4 O’Keefe and colleagues5 also reported a high prevalence of iron deficiency among their patients with RLS. In addition, there is a high prevalence of RLS in populations with iron deficiency (20% to 30%),4,6 in populations associated with a high prevalence of iron deficiency like pregnancy7–9 and blood donors (14% to 26%)10,11 and in populations with altered iron metabolism like occurs in dialysis (14% to 68%).12–14 Although the elderly may have low iron stores due to aging or chronic disease and therefore suffer RLS,5 in the pediatric population, where RLS may be associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),15–17 low iron stores measured by serum ferritin levels have been associated with ADHD,17 RLS,16 and comorbid ADHD and RLS.16–18

Two independent studies demonstrated a strong inverse correlation between serum ferritin levels and RLS severity: as serum ferritin declined, symptom severity increased.5,19 One of the studies also showed a strong correlation between serum ferritin level and sleep efficiency: as ferritin declined, sleep efficiency also declined.19 Despite the findings of these two studies there are limitations to their interpretation. Both evaluated relatively small populations. O’Keefe and associates5 studied an elderly population where the majority of the patients had low-normal or abnormal ferritin levels with a median ferritin level for the group of 33 µg/L (range of 6 to 124 µg/L). Although the patient population studies by Sun and coworkers19 had a much broader range of ferritin levels (5 to 229 µg/L), the mean ferritin was in the low-normal range (60 µg/L). On further analysis of these data,19 patients with low ferritin levels (<50 µg/L) had greater disease severity by several different outcomes measures compared with those with high ferritin levels (>50 µg/L). This finding and others20 suggest that the relation between RLS symptoms and a broad range of body iron storage states may be poor. The relation is strongest when the patients have low or deficient body iron stores, suggesting that iron deficiency per se may be more important than general iron status.

Nordlander3 successively treated RLS symptoms with intravenous iron. The surprising fact is that the majority of these patients had normal blood iron levels. The study implicates a causal link between iron and RLS symptoms and supports his initial premise that “there can exist an iron deficiency in the tissues in spite of normal serum iron.”3 More recent studies have considered the possibility that the brain per se could have low iron stores despite the presence of normal blood or systemic levels of iron. Using magnetic resonance imaging techniques to quantify iron concentrations in 11 brain regions, a first study of RLS patients found lower iron concentrations in their substantia nigra than in age-matched control subjects.21,22 In addition, lower iron concentrations in the substantia nigra were significantly correlated with increasing RLS symptom severity. A second, expanded study confirmed this finding but primarily for early-onset RLS.23 Several studies using transcranial Doppler have confirmed the presence of low levels of iron in the substantia nigra of RLS patients.24–26 The distinction between regulation of body and brain iron levels is made most strikingly by the finding that patients with hemochromatosis—who retain iron and have high ferritin levels—may have reduced brainstem iron.27

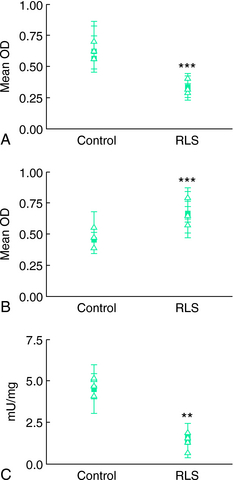

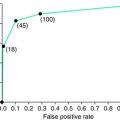

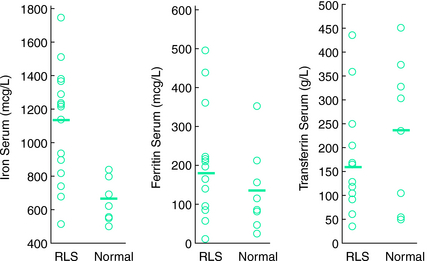

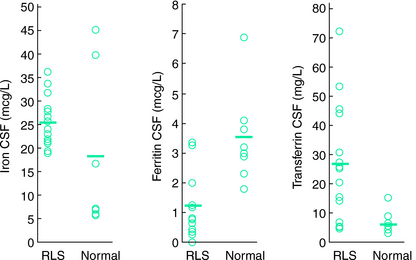

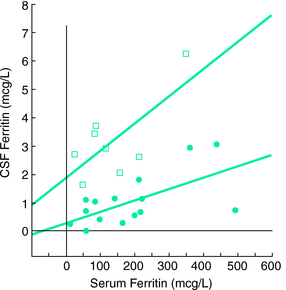

Another study examined cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) ferritin and transferrin as the indicator of brain iron status28 (Figs. 10-1, 10-2, and 10-3 ). Subjects were chosen who had normal blood levels of both of these factors. Despite having normal systemic iron stores that were comparable with those of control subjects, patients with RLS had reduced CSF ferritin and increased CSF transferrin, findings that suggest a relative iron-insufficient state within the central nervous system (CNS). The correlation between serum and CSF ferritin was different for control subjects and RLS patients. The slope of the curve in the RLS group was lower than that found in the control group. This would suggest that CNS iron regulation might be somewhat independent of the systemic iron status in RLS patients. In additional studies using immunoblot techniques and controlling for overall protein quantity, decreased H and L subunits were found in early-, but not late-onset RLS.29 Similarly, depressed levels of prohepcidin, a precursor of the iron regulatory protein hepcidin, were also found in early-onset patients.30

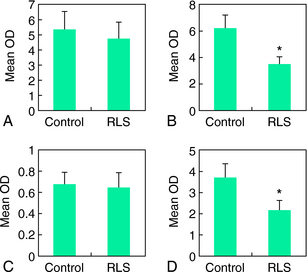

The most conclusive data on the relation of brain iron metabolism to RLS are from brain autopsy analyses31 (Figs. 10-4 and 10-5). General histological assessment of brains from seven RLS patients and five control subjects showed no obvious pathology, cell loss, gliosis, or signs of Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease. Assessments of iron and iron-regulator proteins were specifically evaluated in the substantia nigra because of its high iron and dopaminergic concentrations and because of the previous magnetic resonance imaging findings indicating low iron levels in this area in RLS. In tissues from patients with RLS, iron and H-ferritin were decreased, transferrin was increased, and L-ferritin was the same as for control subjects. However, L-ferritin appeared more concentrated in glial cells in RLS tissue, whereas L-ferritin was predominantly found in oligodendrocytes of control tissues.

A surprising finding was the normal or low-normal levels of transferrin receptor (TfR) protein in RLS tissues. In response to the low tissue iron, TfR protein should have increased to capture more iron. More quantitative analyses performed in neuromelanin cells isolated from the substantia nigra using laser-capture, microdissection techniques showed findings identical to those found with the immunohistochemical technique, including decreased TfR protein32 (Fig. 10-6).

As discussed in Chapter 9, ferritin and TfR synthesis are controlled by one of two iron-responsive proteins (IRP1 and IRP2). Under conditions of iron deficiency, there is increased synthesis of IRP2 and increased conversion of aconitase to IRP1. Increased levels of IRP then result in decreased ferritin and increased TfR. Therefore, to further understand the role of iron-regulator proteins in RLS, the protein levels of both IRPs and aconitase were analyzed in neuromelanin cells that had been isolated from the substantia nigra using laser-capture, microdissection techniques32 (Figs. 10-7 and 10-8).

Neuromelanin cells from RLS tissue had significantly lower IRP1 and elevated IRP2 levels compared with control tissue. The aconitase concentration and its activity were also diminished in RLS tissue. IRP1 seems to be more important for the regulation of TfR synthesis than IRP2.33 This does not appear to be true for IRP control of H-ferritin synthesis. Therefore, lower IRP1 leads to a diminished TfR synthesis, whereas increased IRP2 resulted in the expected decreased H-ferritin synthesis. The basis for the inadequate response or quantitatively diminished IRP1-aconitase remains unknown at this time. The findings would implicate disruption of iron regulation at the level of IRP1 or higher.

A major consideration is how any brain deficiency in RLS causes the emergence of the syndrome. Several lines of evidence suggest how this might occur through alteration of the dopamine system. First, iron can lead to dysfunction in regulation of dopamine system activity. CSF studies of dopamine metabolites show a greater difference between evening and morning values in RLS patients than in control subjects,34 suggesting an enhanced circadian variation of RLS and alterations in metabolism and perhaps increased dopamine synthesis or turnover. Second, a key protein for synapse formation and maintenance, Thy-1, is reduced in RLS dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra.33 Moreover, in animal models, iron deprivation can induce increased circadian variability of dopamine.35

In summary, iron appears to play a key role in RLS.36 There are probably several different triggers by which iron dysregulation may occur. Some of the mechanisms for control of brain iron have been explored in mice and rats and are discussed in Chapter 9. When systemic iron deficiency is induced in different strains of mice, the brain response is quite variable, with some strains showing no change in brain iron whereas others showed decreases in iron.37 In susceptible strains, iron deficiency can produce circadian changes in activity that mimic RLS in showing increased activity at the transition to the rodent rest period.38 A similar finding has been noted in animal models with lesioning of the A11 dopamine system that projects to the spinal cord:39,40 iron deprivation causes greater changes in dopamine receptors and enhanced activity.41 Similarly, in humans, a primary systemic iron deficiency could lead to secondary brain iron insufficiency in a subgroup of the population and thus lead to RLS symptoms. But what about the larger RLS population for whom systemic iron deficiency does not appear to play a role?

When ventral midbrain iron is analyzed across 30 mice strains that were developed from the BXD recombinant inbred mice colony, one can see a three-fold difference in the highest to lowest ventral midbrain iron concentration which had no relation to the systemic levels of iron.42 This would indicate the presence of a complex genetic regulation of brain iron concentrations at the level of the blood-brain barrier or within the cells of the brain that can selectively produce low iron levels without any significant changes in systemic iron concentrations. The parallel to the human condition is important, because it shows the complex genetic nature of brain iron regulation that may exist in humans and account for the changes seen in the RLS brain, despite normal or even increased27 systemic levels of iron.

1. Ekbom KA. Restless legs: A clinical study. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1945;158:1-123.

2. Ekbom KA. Restless legs. A report of 70 new cases. Acta Med Scand. 1950;246:64-68.

3. Nordlander NB. Therapy in restless legs. Acta Med Scand. 1953;145:453-457.

4. Ekbom KA. Restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1960;10:868-873.

5. O’Keeffe ST, Gavin K, Lavan JN. Iron status and restless legs syndrome in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1994;23:200-203.

6. Aspenstroem G. Pica and restless legs in iron deficiency. Sven Lakartidn. 1964;61:1174-1177.

7. Suzuki K, Ohida T, Sone T, et al. The prevalence of restless legs syndrome among pregnant women in Japan and the relationship between restless legs syndrome and sleep problems. Sleep. 2003;26:673-677.

8. Manconi M, Ferini-Strambi L. Restless legs syndrome among pregnant women. Sleep. 2004;27:350. author reply 351

9. Tunc T, Karadag YS, Dogulu F, Inan LE. Predisposing factors of restless legs syndrome in pregnancy. Mov Disord. 2007;22:627-631.

10. Ulfberg J, Nystrom B. Restless legs syndrome in blood donors. Sleep Med. 2004;5:115-118.

11. Gamaldo CE, Benbrook AR, Allen RP, et al. Childhood and adult factors associated with restless legs syndrome (RLS) diagnosis. Sleep Med. 2007;8:716-722.

12. Goffredo Filho GS, Gorini CC, Purysko AS, et al. Restless legs syndrome in patients on chronic hemodialysis in a Brazilian city: Frequency, biochemical findings and comorbidities. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003;61:723-727.

13. Kutner N, Bliwise D. Restless legs complaint in African-American and Caucasian hemodialysis patients. Sleep Med. 2002;3:497-500.

14. Kavanagh D, Siddiqui S, Geddes CC. Restless legs syndrome in patients on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:763-771.

15. Chervin RD, Archbold KH, Dillon JE, et al. Associations between symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, restless legs, and periodic leg movements. Sleep. 2002;25:213-218.

16. Picchietti DL, Stevens HE. Early manifestations of restless legs syndrome in childhood and adolescence. Sleep Med. 2007. ePub

17. Konofal E, Cortese S, Marchand M, et al. Impact of restless legs syndrome and iron deficiency on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Sleep Med. 2007;8:711-715.

18. Oner P, Dirik EB, Taner Y, et al. Association between low serum ferritin and restless legs syndrome in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2007;213:269-276.

19. Sun ER, Chen CA, Ho G, et al. Iron and the restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1998;21:371-377.

20. Berger K, von Eckardstein A, Trenkwalder C, et al. Iron metabolism and the risk of restless legs syndrome in an elderly general population—The MEMO Study. J Neurol. 2002;249:1195-1199.

21. Allen RP, Barker PB, Wehrl F, et al. MRI measurement of brain iron in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2001;56:263-265.

22. Mizuno S, Mihara T, Miyaoka T, et al. CSF iron, ferritin and transferrin levels in restless legs syndrome. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:43-47.

23. Earley CJ, Horska A, Allen RP. MRI-determined regional brain iron concentrations in early- and late-onset restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2006;7:458-461.

24. Schmidauer C, Sojer M, Seppi K, et al. Transcranial ultrasound shows nigral hypoechogenicity in restless legs syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:630-634.

25. Godau J, Schweitzer KJ, Liepelt I, et al. Substantia nigra hypoechogenicity: Definition and findings in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2007;22:187-192.

26. Godau J, Wevers AK, Gaenslen A, et al. Sonographic abnormalities of brainstem structures in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2007. ePub

27. Haba-Rubio J, Staner L, Petiau C, et al. Restless legs syndrome and low brain iron levels in patients with haemochromatosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1009-1010.

28. Earley CJ, Connor JR, Beard JL, et al. Abnormalities in CSF concentrations of ferritin and transferrin in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;54:1698-1700.

29. Clardy SL, Earley CJ, Allen RP, et al. Ferritin subunits in CSF are decreased in restless legs syndrome. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147:67-73.

30. Clardy SL, Wang X, Boyer PJ, et al. Is ferroportin-hepcidin signaling altered in restless legs syndrome? J Neurol Sci. 2006;247:173-179.

31. Connor JR, Boyer PJ, Menzies SL, et al. Neuropathological examination suggests impaired brain iron acquisition in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61:304-309.

32. Connor JR, Wang XS, Patton SM, et al. Decreased transferrin receptor expression by neuromelanin cells in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2004;62:1563-1567.

33. Eisenstein RS. Iron regulatory proteins and the molecular control of mammalian iron metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:627-662.

34. Earley CJ, Hyland K, Allen RP. Circadian changes in CSF dopaminergic measures in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2006;7:263-268.

35. Wang X, Wiesinger J, Beard J, et al. Thy1 expression in the brain is affected by iron and is decreased in restless legs syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2004;220:59-66.

36. Allen RP, Earley CJ. The role of iron in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2007;22:S440-S448.

37. Morse A, Beard JL, Jones B. Behavioral and neurochemical alterations in iron-deficient mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;220:147-152.

38. Dean T Jr, Allen RP, O’Donnell CP, Earley CJ. The effects of dietary iron deprivation on murine circadian sleep architecture. Sleep Med. 2006;7:634-640.

39. Clemens S, Rye D, Hochman S. Restless legs syndrome: Revisiting the dopamine hypothesis from the spinal cord perspective. Neurology. 2006;67:125-130.

40. Ondo WG, Zhao HR, Le WD. Animal models of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2007;8:344-348.

41. Zhao H, Zhu W, Pan T, et al. Spinal cord dopamine receptor expression and function in mice with 6-OHDA lesion of the A11 nucleus and dietary iron deprivation. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1065-1076.

42. Jones BC, Reed CL, Hitzemann R, et al. Quantitative genetic analysis of ventral midbrain and liver iron in BXD recombinant inbred mice. Nutr Neurosci. 2003;6:369-377.

).

).