CHAPTER 1 Introduction to surgery

Evidence-based medicine

Evidence-based medicine is a lifelong process which involves:

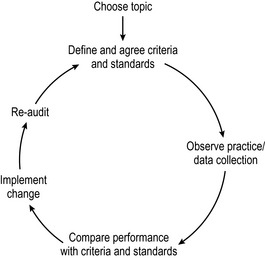

Clinical audit

Clinical audit is a continuous cycle of quality improvement that seeks to improve patient care and service delivery through systematic review of care against explicit criteria and the implementation of change. The clinical audit process is known as the audit cycle. This involves observation of existing practice, the setting of standards, comparison between observed and set standards, implementation of change and re-audit of clinical practice (Fig. 1.1). The main components of the audit cycle are:

Benefits of undertaking clinical audit:

Consent

For consent to be valid, the patient must have the capacity to:

Consent should be informed, i.e. the patient should be given the full information about:

Consent must be voluntary, i.e. not the result of coercion by medical staff, relatives or friends.

Medico-legal issues

Death and the certification of death

When you are qualified, you will be required to diagnose death. The patient is pulseless, apnoeic, and has fixed, dilated pupils. Auscultation reveals no heart sounds or breath sounds. If the patient is on a ventilator, brain death may be diagnosed even although the heart is still beating. The preconditions and the criteria for testing for brain death are explained in Chapter 18. Do not forget that after death, organs and tissue may be donated for transplantation purposes. Any solid organ and tissues may be removed from a ventilated brain-dead patient but remember that kidneys may be removed within 30 min of death and other tissues such as cornea, bone, skin and heart valves may be removed within 24 h of death.

Taking a history

The remainder of the history should be taken in the following order:

Examination of a lump

History

Examination

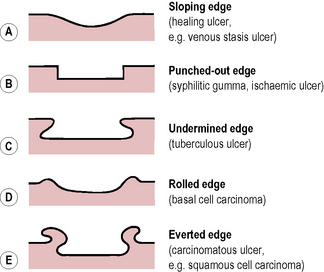

Examination of an ulcer

History

Classification of disease

When initially starting your surgical training, your knowledge will be limited. You will, therefore, find it difficult to reach a diagnosis. In order to do this you should go through a broad classification of the aetiology of disease as shown in Table 1.1. This is sometimes known as the ‘surgical sieve’. Ask yourself, is this lesion congenital (usually easy to decide) or is it acquired? If it is acquired, then go through the ‘sieve’ and try and decide which classification it belongs to. As you learn more pathology and more surgery, you will still find this classification suitable when trying to reach a differential diagnosis. It is a good idea when you are first learning, with every disease, lump or ulcer you meet, to sit down and go through the ‘surgical sieve’ and decide which of these groups it belongs to.

| Congenital |

| Acquired |

| Traumatic |

| Inflammatory: |