CHAPTER 1 Introduction

Within anesthetic practice, the role of regional anesthesia – including peripheral nerve block – has expanded greatly over the past two decades. In 1998, a national survey demonstrated that 87.8% of US anesthesiologists make use of regional techniques.1 This widespread use arises in part from the widely held belief (to some extent evidence-based) that, at least in some settings, anesthetic techniques that avoid general anesthesia offer real advantages in terms of patient outcome.2 For instance, Chelly and colleagues have demonstrated clearly that continuous femoral infusion of ropivacaine 0.2% in patients undergoing total knee replacement provides better postoperative analgesia than epidural or patient-controlled analgesia. Critically, this technique accelerated early functional recovery and was associated with decreased duration of hospital stay, postoperative blood loss, and incidence of serious postoperative complications.3

A second reason that accounts for the recent increase in peripheral nerve block practiced in developed countries is the greater proportion of surgical procedures carried out as ‘day cases’. Regional anesthesia plays a fundamental role in the future of day case or ambulatory anesthesia, both as an intrinsic component of the anesthetic technique and for effective postoperative analgesia.4 Currently, 60–70% of all surgical procedures performed in the USA are day cases. It is likely that peripheral nerve block, used appropriately in the ambulatory setting, decreases the time to discharge from hospital, improves patient satisfaction and postoperative analgesia, facilitates rehabilitation, and results in fewer complications than conventional analgesic techniques.

The readership most likely to benefit

It is widely recognized that anesthetists are incompletely trained unless they are proficient in the performance of peripheral nerve block.5 Anesthetists comprise the single largest group of hospital doctors. Approximately 5% of all physicians in the USA practice anesthesia. In some countries, anesthesia is also practiced by nurse anesthetists.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Equipment

We used the Toshiba 0.35T OPART, open system.6 This scanner uses superconducting technology and high-speed gradients to produce high-quality images. The scanner was selected on the basis of its well-documented advantages; namely, that its open architecture allows comfortable volunteer positioning, easy access for injection, and prevents problems associated with claustrophobia.7–9 A number of transmit and receive coils were used, appropriate to the anatomic area being scanned.

Physical principles

In diagnostic MRI, contrast agents are used to enhance the contrast between normal tissue and pathology. This is more important on T1-weighted images, where water and tumors demonstrate similar low-signal intensities. The use of contrast agents selectively affects the T1 and T2 times of these tissues.10 We used contrast to imitate and visualize the degree of spread of local anesthetic and to highlight anatomic structures.

Contrast agent

The contrast agent used is a gadolinium (Gd)-based agent; Gd is a paramagnetic material that has a positive effect on the local magnetic field. When it is near water, which has long T1 and T2 times, it causes a change in the local magnetic moment of the adjacent water molecules. This has the effect of reducing the T1 relaxation time of water, which allows water to give higher signal intensity on T1-weighted images. Thus Gd and other paramagnetic substances are known as T1 enhancement agents.11

As a free ion, Gd is quite toxic and has a biological half-life of several weeks, the kidneys and liver demonstrating greatest uptake. For this reason, Gd is aligned with a substance known as a chelate. The chelate works by attaching to eight of the nine free-binding sites of the Gd molecule. This reduces Gd’s toxic effect because it facilitates faster excretion. The contrast agent that we used was gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist), which has the Gd molecule attached to a chelate called diethylenetriaminepenta-acetic acid (DTPA). This produces the complex molecule Gd-DTPA and is a relatively safe, water-soluble contrast agent. However, the addition of a chelate affects the ability of the Gd to reduce the T1 recovery time of the adjacent tissue. Thus the use of a chelate must take into consideration the rate of uptake of the Gd-DTPA agent, the relative T1 recovery time of the tissue, and the safety of the complex.12 The contrast was diluted to 1 : 250 in order to obtain the best signal. This level of dilution was selected following serial testing (on ‘phantoms’) using different degrees of dilution.

Image characteristics

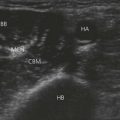

There are a number of different sequences available to MRI scanners. We used T1-weighted spin echo sequences primarily, supplemented by fat-saturated sequences. T1-weighted MR images show very good soft-tissue contrast and also show enhancement from Gd-based contrast agents. As explained, due to differing relaxation times of fat and water on T1-weighted tissues, fat displays as high signal (bright) and water displays as low signal (dark).10 In the images where contrast is displayed, the short relaxation time of the Gd-based contrast agent enables the contrast to have high signal. On some images, the high signal of both fat and contrast may be similar, but by comparing with precontrast images and fat-saturated images it is possible to differentiate between the signals.

1 Hadzic A, Vloka JD, Kuroda MM, et al. The practice of peripheral nerve blocks in the United States: a national survey. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:241-246.

2 Mingus ML. Recovery advantages of regional compared with general anesthesia: adult patients. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:628-633.

3 Chelly JE, Greger J, Gebhard R, et al. Continuous femoral nerve blocks improve recovery and outcome of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Arthroplasty. 2001;16:436-445.

4 White PF, Smith I. Ambulatory anesthesia: past, present and future. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1994;32:1-16.

5 Kopacz DJ, Bridenbaugh CD. Are anesthetic residencies failing regional anesthesia? Reg Anesth. 1993;18:84-87.

6 Toshiba Corp. MRI system, OPART, product information. Toshiba Corp; 1998.

7 Dworkin JS. Open field magnetic resonance imaging; system and environment. The technology and potential of open magnetic resonance imaging. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2000.

8 Kaufman L, Carlson J, Li A, et al. Open-magnet technology for magnetic resonance imaging. In: Open field magnetic resonance imaging: equipment, diagnosis and interventional procedures. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2000.

9 Spouse E, Gedroyc WM. MRI of the claustrophobic patient: interventionally configured magnets. Br J Radiol. 2000;73:146-151.

10 Westbrook C, Kaut C. MRI in practice, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1998. 252–258

11 Muroff L. MRI contrast: current agents and issues. Appl Radiol. 2001;30(8):8-14.

12 Runge V. The safety of MR contrast media: a literature review. Appl Radiol. 2001;30(8):5-7.