9 Intravenous Regional Block

Perspective

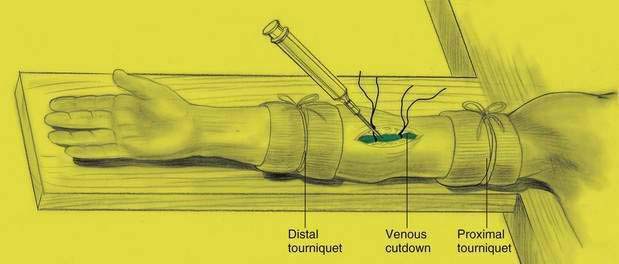

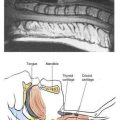

Intravenous (IV) regional anesthesia was introduced by Bier in 1908. As illustrated in Figure 9-1, in the initial description a surgical procedure was required to cannulate a vein, and both proximal and distal tourniquets were used to contain the local anesthetic in the venous system. After its introduction, the technique fell into disuse until the less toxic amino amides became available in the mid-20th century. This technique can be used for a variety of upper extremity operations, including both soft tissue and orthopedic procedures, primarily in the hand and forearm. The technique has also been used for foot procedures with a calf tourniquet.

Placement

Position

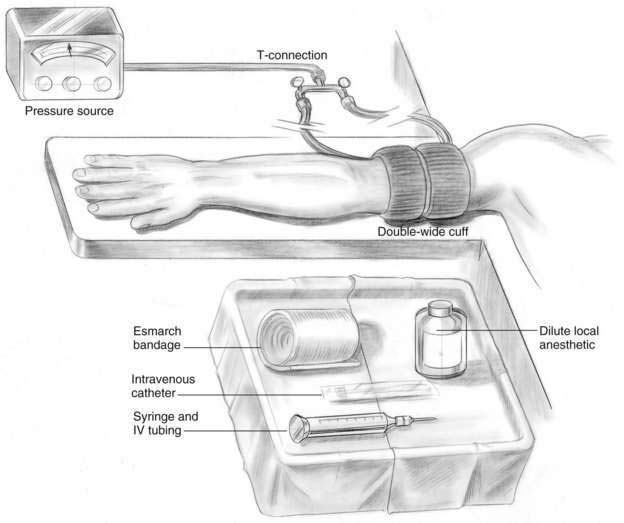

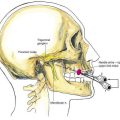

The patient should be resting supine on the operating table with an IV tube already established in the nonsurgical arm. The involved arm should be extended on an arm board near available supplies (Fig. 9-2).

Needle Puncture

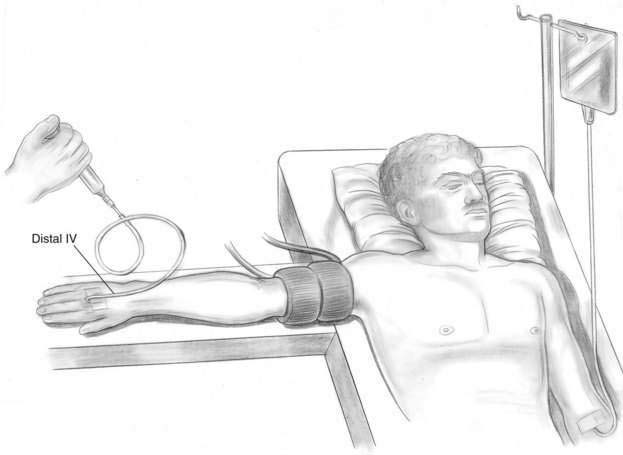

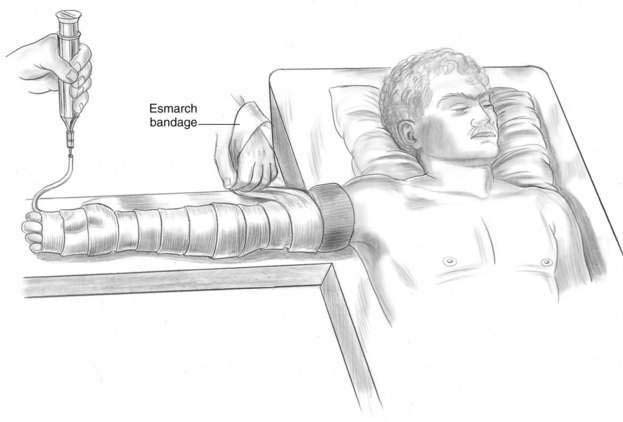

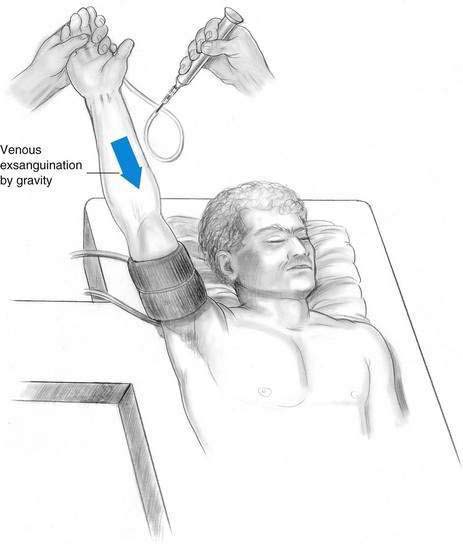

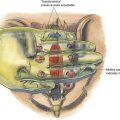

Before placement of the IV catheter in the operative extremity, a tourniquet, either double or single, should be placed around the upper arm of the patient. An IV cannula is then inserted in the operative extremity, as distally as possible, most commonly in the dorsum of the hand (Fig. 9-3). There are two methods for exsanguinating the venous blood from the operative extremity. The traditional technique requires the wrapping of an Esmarch bandage from distal to proximal (Fig. 9-4). When the Esmarch bandage is not available or the patient is in too much pain to allow its placement, another method is to raise the arm for 3 to 4 minutes to allow gravity to exsanguinate the operative upper extremity (Fig. 9-5). After the blood has been exsanguinated from the upper extremity, the tourniquet is inflated. If a double tourniquet is used, only the upper tourniquet is inflated. Recommendations for tourniquet inflation pressures range from 50 mm Hg above systolic blood pressure with a wide cuff, to a cuff pressure double the systolic blood pressure, to 300 mm Hg regardless of blood pressure. Until more information is available, I caution against using pressures greater than 300 mm Hg during upper extremity block.

Pearls

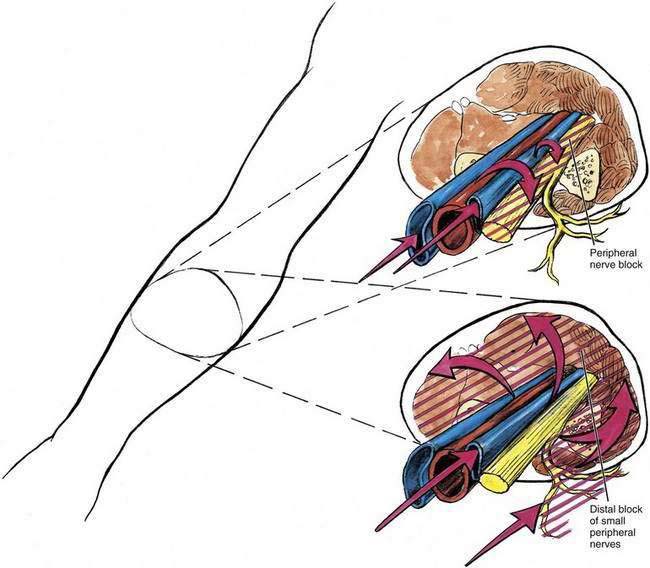

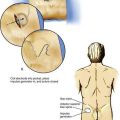

Figure 9-6 illustrates the two complementary theories of how IV regional anesthesia produces block. The figure conceptualizes local anesthetic entering the venous system and producing block by blocking the peripheral nerves running with the venous structures. It also outlines a theory that may be complementary—that is, the local anesthetic leaves the veins and blocks small distal branches of peripheral nerves. It is likely that both of these theories are operative. If IV regional anesthesia is to be used successfully, all members of the operating team should understand the importance of tourniquet integrity because the most significant problems with the technique involve unintentional deflation of the tourniquet.