Chapter 2 Intravascular contrast media

Historical Development of Radiographic Agents

The first report of opacification of the urinary tract after intravenous (i.v.) injection of a contrast agent appeared in 1923, when Osborne et al. took advantage of the fact that i.v.-injected, 10% sodium iodide solution, which was then used in the treatment of syphilis, was excreted in the urine. In 1928 German researchers synthesized a compound with a number of pyridine rings containing iodine in an effort to detoxify the iodine. This mono-iodinated compound was developed further into di-iodinated compounds and subsequently in 1952 the first tri-iodinated compound, sodium acetrizoate (Urokon), was introduced into clinical radiology. Sodium acetrizoate was based on a 6-carbon ring structure, tri-iodo benzoic acid, and was the precursor of all modern water-soluble contrast media.

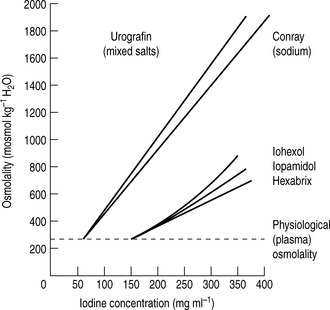

Until the early 1970s all contrast media were ionic compounds and were hypertonic with osmolalities of 1200–2000 mosmol kg−1 water, 4–7 × the osmolarity of blood. These are referred to as high osmolar contrast media (HOCM) and are distinguished by differences at position 5 of the anion and by the cations sodium and/or meglumine. In 1969 Almén first postulated that many of the adverse effects of contrast media were the result of high osmolality and that by eliminating the cation, which does not contribute to diagnostic information but is responsible for up to 50% of the osmotic effect, it would be possible to reduce the toxicity of contrast media.1

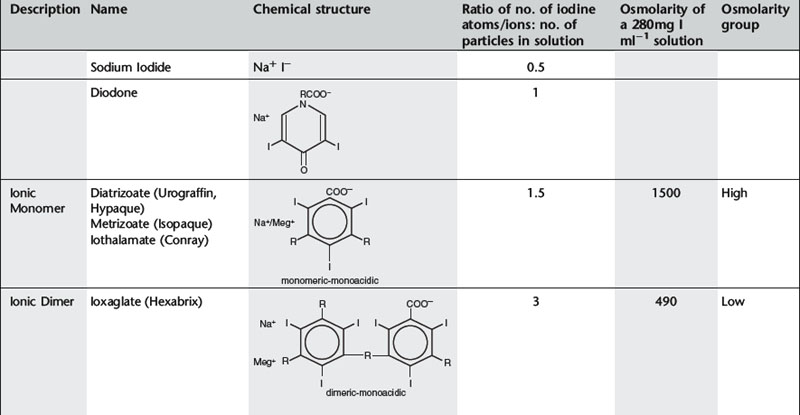

Conventional ionic contrast media had a ratio of three iodine atoms per molecule to two particles in solution, i.e. a ratio of 3:2 or 1.5 (Table 2.1). In order to decrease the osmolality without changing the iodine concentration, the ratio between the number of iodine atoms and the number of dissolved particles must be increased.

Further development proceeded along two separate paths (Table 2.1). The first was to combine two tri-iodinated benzene rings to produce an ionic dimer with six iodine atoms per anion, the low osmolar contrast medium (LOCM) ioxaglate (Hexabrix). Replacement of one of the carboxylic acid groups with a non-ionizing radical means that only one cation is needed per molecule. The alternative, more successful, approach was to produce a compound that does not ionize in solution and so does not provide radiologically useless cations. Contrast media of this type are referred to as non-ionic and are also LOCM. These include the non-ionic monomers iopamidol (Niopam, Iopamiron, Isovue, and Solutrast), iohexol (Omnipaque), iopromide (Ultravist), iomeprol (Iomeron) and ioversol (Optiray).

For both types of LOCM the ratio of iodine atoms in the molecule to the number of particles in solution is 3:1 and osmolality is decreased. Compared with high osmolar contrast material (HOCM), the LOCM show a theoretical halving of osmolality for equi-iodine solutions. However, because of aggregation of molecules in solution the measured reduction is approximately one-third (Fig. 2.1).

Figure 2.1 A plot of osmolality against iodine concentration for new and conventional contrast media. From Dawson et al.2

(Reproduced by courtesy of the editor of Clinical Radiology.)

A further development in the search for the ideal contrast agent has been the introduction of non-ionic dimers – iotrolan (Isovist) and iodixanol (Visipaque). These have a ratio of six iodine atoms for each molecule in solution with satisfactory iodine concentrations at iso-osmolality; they are, therefore, called iso-osmolar contrast media. The safety profile of the iso-osmolar contrast agents is at least equivalent to LOCM, but any significant advantage of iso-osmolar contrast remains controversial.

The low- and iso-osmolar contrast media are 5–10 times safer than the HOCM.3 Previously, HOCM were much less expensive than LOCM so were widely used despite the higher risk of adverse reaction and nephrotoxicity. LOCM were reserved for use in patients considered to be at increased risk of contrast reaction. Over the past few years, the relative cost of the non-ionic contrast media has fallen and the use of ionic contrast medium for i.v. injection has now ceased almost entirely. Ionic contrast media must never be used in the subarachnoid space.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF INTRAVENOUS WATER-SOLUBLE CONTRAST MEDIA

Adverse reactions after administration of non-ionic iodinated contrast media are rare, occuring in less than 1% of all patients.4 Of these reactions, the majority are mild and self-limiting. The incidence of severe or very severe non-ionic contrast reaction is 0.044%.5

TOXIC EFFECTS ON SPECIFIC ORGANS

Vascular toxicity

Cardiovascular toxicity

Haematological changes

Nephrotoxicity

The mechanisms of CIN are summarized below:10

It was hoped that the iso-osmolar contrast agents might be less nephrotoxic than LOCM and HOCM. However, clinical trials have so far yielded conflicting results.9,11 CIN has a complex aetiology and the positive benefit of reduction in osmolarity achieved with iso-osmolar contrast medium may be negated by the accompanying increase in viscosity.12

See Table 2.3 for guidelines on prophylaxis of renal adverse reaction to iodinated contrast.

IDIOSYNCRATIC REACTIONS

Excluding death, adverse reactions can be classified in terms of severity as:

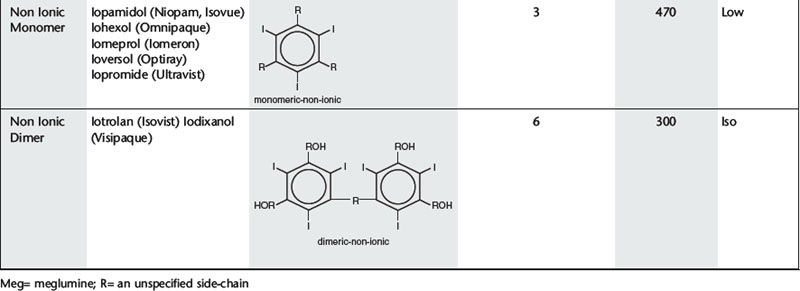

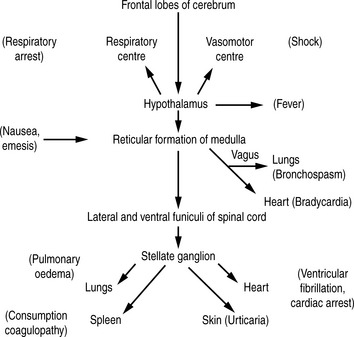

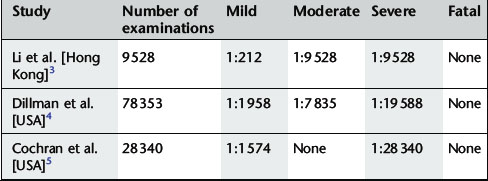

Minor and intermediate reactions are not uncommon; major adverse reactions are rare (Table 2.2).

Fatal reactions

Deaths caused by iodinated contrast agents are very rare, occuring at a rate of 1.1–1.2 per million contrast media packages distributed. Most are attributed to renal failure, anaphylaxis or allergic reaction.18

Almost all fatal reactions occur in the minutes following injection and patients must be under close observation during this time. The fatal event may be preceded by trivial events, such as nausea and vomiting, or may occur without warning. The majority of deaths occur in those over 50 years of age. Causes of death include cardiac arrest, pulmonary oedema, respiratory arrest, consumption coagulopathy, bronchospasm, laryngeal oedema and angioneurotic oedema.

Non-fatal reactions

MECHANISMS OF IDIOSYNCRATIC CONTRAST-MEDIUM REACTIONS

Idiosyncratic contrast medium reactions are usually labelled anaphylactoid since they have all the features of anaphylaxis but are IgE negative in most cases.20 Possible mechanisms include those outlined below.

Complement activation

Contrast medium may activate the complement system leading to the formation of anaphylatoxins which induce the release of histamine and other biological mediators from basophils and mast cells.20 However, there is uncertainty as some studies have failed to show an increase in complement fraction levels in patients after reaction to i.v. iodinated contrast.

Protein binding, enzyme inhibition and immune receptors

Contrast media are weakly protein bound and the degree of protein binding correlates well with their ability to inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. Contrast medium side-effects such as vasodilatation, bradycardia, hypotension, bronchospasm and urticaria are all recognized cholinergic effects. It was previously thought that they might be related more to cholinesterase inhibition than osmolality; however, this has not been conclusively proven. More recently, it has been postulated that weakly protein bound drugs, such as iodinated contrast, may directly activate T cells which bear immune receptors. It is thought that these may interact with the drug and that contrast medium may have an effect on cytokine production by helper T cells21 to mediate the acute reaction.

Chemotoxicity

Although the major adverse effect on erythrocytes is due to hyperosmolality, even contrast medium which is iso-osmolar with plasma produces changes in red-blood-cell morphology that reveal the intrinsic chemotoxicity of contrast medium molecules.

Anxiety

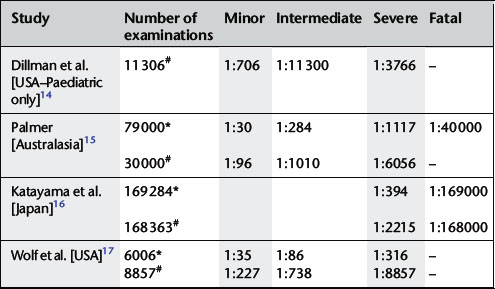

Many years ago, Lalli22 postulated that most, if not all, contrast medium reactions are the result of the patient’s fear and apprehension. The high autonomic nervous system activity in an anxious patient will be stimulated further when the patient experiences the administration of contrast medium. Furthermore, contrast medium crossing the blood–brain barrier can stimulate the limbic area and hypothalamus to produce further autonomic activity. This autonomic activity is responsible for contrast medium reactions by the sequence of events illustrated in Figure 2.2.

PROPHYLAXIS OF ADVERSE CONTRAST MEDIUM EFFECTS

Guidelines for prophylaxis of renal and non-renal adverse contrast media reaction are given in Tables 2.3 and 2.4. Sources used in these tables include documents of the Royal College of Radiologists3 and the European Society of Urogenital Radiology23 on contrast medium administration; the full text of these documents can be downloaded from the internet at www.rcr.ac.uk and www.esur.org respectively. General safety issues are:

Table 2.3 Guidelines for prophylaxis of renal adverse reactions to iodinated contrast medium

| Renal adverse reactions |

|---|

| Identification of patients at increased risk: |

|

1. The referring clinician should identify patients with pre-existing renal impairment and inform the radiology department.

|

Table 2.4 Guidelines for prophylaxis of non-renal adverse reactions to iodinated contrast medium

| Non-renal adverse reactions |

|---|

| Identification of patients at increased risk of anaphylactoid contrast reaction: |

| It is essential that before administration of iodinated contrast every patient must be specifically asked whether they have a history of:

1. previous contrast reaction – associated with a sixfold increase in reactions to contrast medium.20 Determine exact nature and specific agent used.

2. asthma – history of asthma associated with a six to tenfold increase in risk of severe reaction.24 Determine whether patient has true asthma or COPD and whether asthma is currently well controlled. If asthma not currently well controlled and examination is non-emergency, the patient should be referred back for appropriate medical therapy.

|

| Precautions for patients at increased risk of anaphylactoid contrast reaction: |

| There are no conclusive data supporting the use of premedication in the prevention of severe reactions to contrast media in patients at increased risk and clinical opinion remains divided.25,26 |

| If it is decided to use premedication for patients at increased risk, a suitable regime is prednisolone 30 mg orally given 12 h and 2 h before contrast medium. |

| Pre-treatment with antihistamines is of no benefit and is associated with an increased incidence of flushing. Pre-testing by applying contrast medium to the cornea or injecting a 1 ml test dose intravenously a few minutes prior to the full injection has also been abandoned. |

| Other situations: |

| Pregnancy – In exceptional circumstances, iodinated contrast may be given. Thyroid function of the neonate should be checked during the first week of life.27 |

| Treatment with ß-blockers – ß-blockers may impair the response to treatment of bronchospasm induced by contrast medium. |

| Lactation – No special precaution required. Breast feeding can continue normally. |

| Thyrotoxicosis – Intravascular contrast should not be given if the patient is hyperthyroid. Avoid thyroid radio-isotope tests and treatment for 2 months after iodinated contrast medium administration. |

| Phaeochromocytoma – When detected biochemically it is advised that α and ß-adrenergic blockade with orally administered drugs is arranged before administration of iodinated contrast. |

| Sickle cell anaemia – There is risk of precipitating a sickle cell crisis. Iso-osmolar contrast should be used. |

| Myelomatosis – Bence Jones protein may be precipitated in renal tubules. Risk diminished by ensuring good hydration. |

1 Almén T. Contrast agent design. Some aspects of synthesis of water-soluble contrast agents of low osmolality. J. Theor. Biol.. 1969;24:216-226.

2 Dawson P., Grainger R.G., Pitfield J. The new low-osmolar contrast media: a simple guide. Clin. Radiol.. 1983;34:221-226.

3 The Royal College of Radiologists. Standards for Intravenous Iodinated Contrast Administration to Adult Patients. London: The Royal College of Radiologists, 2005.

4 Mortelé K.J., Oliva M.R., Ondategui S., et al. Universal use of nonionic iodinated contrast medium for CT: evaluation of safety in a large urban teaching hospital. Am. J. Roentgenol.. 2005;184(1):31-34.

5 Katayama H., Yamaguchi K., Kozuka T., et al. Adverse reactions to ionic and non-ionic contrast media. Radiology. 1990;175(3):621-628.

6 Dawson P., McCarthy P., Allison D.J., et al. Non-ionic contrast agents, red cell aggregation and coagulation. Br. J. Radiol.. 1988;61:963-965.

7 Aspelin P., Stacul F., Thomsen H.S., et al. Effects of iodinated contrast media on blood and endothelium. Eur. Radiol.. 2006;16(5):1041-1049.

8 Losco P., Nash G., Stone P., et al. Comparison of the effects of radiographic contrast media on dehydration and filterability of red blood cells from donors homozygous for hemoglobin A or hemoglobin. S. Am. J. Hematol. 2001;68(3):149-158.

9 Benko A., Fraser-Hill M., Magner P., et al. Canadian Association of Radiologists: consensus guidelines for the prevention of contrast induced nephropathy. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J.. 2007;58(2):79-87.

10 Persson P.B., Hansell P., Liss P. Pathophysiology of contrast medium-induced nephropathy. Kidney Int.. 2005;68(1):14-22.

11 Liss P., Persson P.B., Hansell P., et al. Renal failure in 57 925 patients undergoing coronary procedures using iso-osmolar or low-osmolar contrast media. Kidney Int.. 2006;70(10):1811-1817.

12 Brunette J., Mongrain R., Rodés-Cabau J., et al. Comparative rheology of low- and iso-osmolarity contrast agents at different temperatures. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv.. 2008;71(1):78-83.

13 van der Molen A.J., Thomsen H.S., Morcos S.K., et al. Effect of iodinated contrast media on thyroid function in adults. Eur. Radiol.. 2004;14(5):902-907.

14 Dillman J.R., Strouse P.J., Ellis J.H., et al. Incidence and severity of acute allergic-like reactions to i.v. non-ionic iodinated contrast material in children. Am. J. Roentogenol.. 2007;188(6):1643-1647.

15 Palmer F.J. The R.A.C.R. survey of intravenous contrast media reactions: final report. Australas. Radiol.. 1988;32:426-428.

16 Katayama H., Yamaguchi K., Kozuka T. Adverse reactions to ionic and non-ionic contrast media. A report from the Japanese Committee on the Safety of Contrast Media. Radiology. 1990;175:621-628.

17 Wolf G.L., Mishkin M.M., Roux S.G. Comparison of the rates of adverse drug reactions. Ionic contrast agents, ionic agents combined with steroids and nonionic agents. Invest. Radiol.. 1991;26:404-410.

18 Wysowski D.K., Nourjah P. Deaths attributed to X-ray contrast media on U.S. death certificates. Am. J. Roentgenol.. 2006;186:613-615.

19 Webb J.A., Stacul F., Thomsen H.S., et al. Late adverse reactions to intravascular iodinated contrast media. Eur. Radiol.. 2003;13(1):181-184.

20 Morcos S.K. Acute serious and fatal reactions to contrast media: our current understanding. Br. J. Radiol.. 2005;78(932):686-693.

21 Böhm I., Speck U., Schild H. Cytokine profiles after nonionic dimeric contrast medium injection. Invest. Radiol.. 2003;38(12):776-783.

22 Lalli A.F. Urographic contrast media reactions and anxiety. Radiology. 1974;112(2):267-271.

23 European Society of Urogenital Radiology Contrast Media Safety Committee. ESUR guidelines on contrast media Version 6.0. www.esur.org, 2007.

24 Morcos S.K., Thomsen H.S. Adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media. Eur. Radiol.. 2001;11(7):1267-1275.

25 Tramèr M.R., von Elm E., Loubeyre P., et al. Pharmacological prevention of serious anaphylactic reactions due to iodinated contrast media: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;333(7570):675.

26 Thomsen H.S. Guidelines for contrast media from the European Society of Urogenital Radiology. Am. J. Roentgenol.. 2003;181:1463-1471.

27 Webb J.A., Thomsen H.S., Morcos S.K., et al. The use of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media during pregnancy and lactation. Eur. Radiol.. 2005;15(6):1234-1240.

Contrast Agents in Magnetic Resonance Imaging

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT

Shortly after the introduction of clinical MRI, the first contrast-enhanced human MRI studies were reported in 1981 using ferric chloride as a contrast agent in the gastrointestinal tract. In 1984, Carr et al. first demonstrated the use of a gadolinium compound as a diagnostic intravascular MRI contrast agent.1 Currently, around one-quarter of all MRI examinations are performed with contrast agents.

MECHANISM OF ACTION

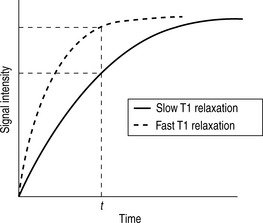

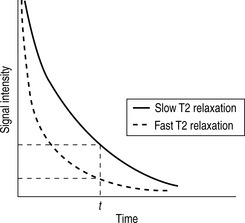

Whilst radiographic contrast agents use a direct alteration in tissue density to allow the visualization of structures, the MRI contrast agents act indirectly by altering the magnetic properties of hydrogen ions (protons) in water and lipid which form the basis of the image in MRI. To enhance the inherent contrast between tissues, MRI contrast agents must alter the rate of relaxation of protons within the tissues. The changes in relaxation vary and, therefore, different tissues produce differential enhancement of the signal (see Figs 2.3 and 2.4). These figures show that, for a given time t, if the T1 relaxation is more rapid then a larger signal is obtained (brighter images), but the opposite is true for T2 relaxation, where more rapid relaxation produces reduced signal intensity (darker images). There are different means by which these effects on protons can be produced using a range of MRI contrast agents.

MRI contrast agents must exert a large magnetic field density (a property imparted by their unpaired electrons) to interact with the magnetic moments of the protons in the tissues and so shorten their T1 relaxation time which will produce an increase in signal intensity (see Fig. 2.3). The electron magnetic moments also cause local changes in the magnetic field, which promotes more rapid proton dephasing and so shortens the T2 relaxation time. All contrast agents shorten both T1 and T2 relaxation times but some will predominantly affect T1 (longitudinal relaxation rate) and other predominantly T2 (transverse relaxation rate).

GADOLINIUM

Adverse reactions

Gadolinium contrast agents are very safe and well tolerated; they have a much lower incidence of adverse reactions than iodinated contrast agents. Adverse reactions to gadolinium are mostly mild and self-limiting and can be divided into acute and delayed reactions. The incidence is shown in Table 2.5.

Acute adverse reactions

These are rare, but the following have been described:

Patients with a history of previous adverse reaction to gadolinium contrast agents have up to an eightfold increase in likelihood of experiencing adverse reactions,6 and those with asthma, documented allergies or previous adverse reaction to iodinated contrast are also at increased risk of adverse reaction.7

Delayed adverse reactions

Precautions for prevention of adverse reactions

Detailed guidelines are available from the American College of Radiology7 and the European Society of Urogenital Radiology.11 These form the basis for the following advice.

Acute adverse reactions

Delayed adverse reaction

IRON-OXIDE MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING CONTRAST AGENTS (SPIO AND USPIO)

After i.v. injection, the superparamagnetic SPIO contrast agents are taken up via the reticulo-endothelial system into the liver and spleen resulting in decreased signal intensity in normal liver and spleen on T2-weighted images. Malignant tumour tissue or other lesions which do not contain reticulo-endothelial cells will not take up the contrast and, therefore, retain their high MRI signal. Iron-oxide contrast agents are useful for detection of liver tumour, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma.12

The USPIO contrast agents have greater T1 shortening effects and a longer plasma circulation time than the SPIO agents. In addition, they have greater uptake in bone marrow and lymph nodes and their use for imaging bone marrow and lymph nodes is being developed.13

GASTROINTESTINAL CONTRAST AGENTS

MRI Contrast agents in Pregnancy and Lactation

Only tiny amounts of gadolinium based contrast medium given intravenously to a lactating mother reach the milk and a minute proportion entering the baby’s gut is absorbed. The very small risk associated with absorption of contrast medium may be considered insufficient to warrant stopping breast feeding for 24 h following gadolinium contrast agents.14

1 Carr D.H., Brown J., Bydder G.M., et al. Intravenous chelated gadolinium as a contrast agent in NMR imaging of cerebral tumours. Lancet. 1984;1(8375):484-486.

2 Fink C., Goyen M., Lotz J. Magnetic resonance angiography with blood-pool contrast agents: future applications. Eur. Radiol.. 2007;17(Sup 2):B38-44.

3 Li A., Wong C.S., Wong M.K., et al. Acute adverse reactions to magnetic resonance contrast media- gadolinium chelates. Br. J. Radiol.. 2006;79:368-371.

4 Dillman J.R., Ellis J.H., Ellis J.H., et al. Frequency and severity of acute allergic-like reactions to gadolinium-containing i.v. contrast media in children and adults. Am. J. Roentgenol.. 2007;189(6):1533-1538.

5 Cochran S.T., Bomyea K., Sayre J.W. Trends in adverse events after iv administration of contrast media. Am. J. Roentgenol.. 2001;176(6):1385-1388.

6 Nelson K.L., Gifford L.M., Lauber-Huber C., et al. Clinical safety of gadopentetate dimeglumine. Radiology. 1995;196(2):439-443.

7 Kanal E., Barkovich A.J., Bell C., et al. ACR guidance document for safe MR practices. Am. J. Roentgenol.. 2007;188(6):1447-1474.

8 Thomsen H.S., Almèn T., Morcos S.K. Gadolinium-containing contrast media for radiographic examinations: a position paper. Eur. Radiol.. 2002;12(10):2600-2605.

9 Cowper S.E., Robin H.S., Steinberg S.M., et al. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356(9234):1000-1001.

10 Kuo P.H., Kanal E., Abu-Alfa A.K., et al. Gadolinium-based MR contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Radiology. 2007;242(3):647-649.

11 www.esur.org/fileadmin/Guidelines/ESUR_2007_Guideline_6_Kern_Ubersicht_pdf.

12 Gandhi S.N., Brown M.A., Wong J.G., et al. MR contrast agents for liver imaging: what, when, how. Radiographics. 2006;26(6):1621-1636.

13 Misselwitz B. MR contrast agents in lymph node imaging. Eur. J. Radiol.. 2006;58(3):375-382.

14 Webb J.A., Thomsen H.S., Morcos S.K., et al. The use of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media during pregnancy and lactation. Eur. Radiol.. 2005;15(6):1234-1240.

Contrast Agents in Ultrasonography

During the late 1960s, studies were published describing the intracardiac injection of agents during echocardiography, which were the first reported use of ultrasound (US) contrast. Considerable progress has now been made in the development and clinical application of US contrast agents. These agents contain microbubbles of air, nitrogen or fluorocarbon gas coated with a thin shell of material such as albumin, galactose or lipid. The contrast is often injected intravenously, but in order to cross the pulmonary filter and reach the arterial circulation the microbubbles must be smaller than 7 μm, approximately the size of a red blood cell. Bubbles of this size only remain intact for a very short time in blood. All US contrast media are echo-enhancers and their effect is based on the marked difference in acoustic impedance between microbubbles and surrounding blood or tissue.1

Clinical applications of US contrast agents include the following:2

The US agents in clinical use are well tolerated and serious adverse reactions are rarely observed. Allergy-like reactions occur rarely and adverse events are usually mild and self-resolving.3

1 Calliada F., Campani R., Bottinelli O., et al. Ultrasound contrast agents: basic principles. Eur. J. Radiol.. 1998;27:S157-S160.

2 Quaia E. Microbubble ultrasound contrast agents: an update. Eur. Radiol.. 2007;17(8):1995-2008.

3 Jakobsen J.A., Oyen R., Thomsen H.S., et al. Safety of ultrasound contrast agents. Eur. Radiol.. 2005;15(5):941-945.