Chapter 179 Intraoperative Nonparalytic Monitoring

Wake-Up Test

A number of methods have been developed for the intraoperative monitoring of spinal cord function. The earliest documented systematic approach to the intraoperative monitoring of spinal cord function was the wake-up test.1 Commonly referred to as the Stagnara wake-up test, this technique often provides an unequivocal demonstration of the integrity of long motor tract function. However, it provides this information for one point in time and, in fact, is observed after any potentially harmful surgical manipulation has already taken place. The ability to monitor evoked potentials accurately has made the need for this test less common.1–4

In 1973, Vauzelle et al.5 described the intraoperative wake-up test, which is still considered the gold standard by some centers. It enables the surgeon to perform a brief neurologic examination to the sedated but arousable patient and to directly evaluate the functional integrity of the neuronal structures. The patient is awoken from general anesthesia prior to wound closure, allowing the surgeon to assess for any neurologic deficits that may have resulted from surgical manipulation or instrumentation. If there is a neurologic deficit, the deformity correction and/or instrumentation can be revised immediately.

The requirements of the intraoperative wake-up test are simple. The patient must be told that the test may be performed. If the test is anticipated, a full explanation must ensue, describing the procedure and expected conditions on awakening (i.e., intubation, confusion, levels of discomfort).6

Once awakened, the patient is asked to appropriately move the arms and legs (e.g., “squeeze my hand,” “wiggle your toes”). Discovered deficits require reevaluation of the patient’s position, the instrumentation, and consideration of vascular compromise. Therefore, both the surgeon and anesthesia team must be prepared for reawakening following their initial assessment. The use of the intraoperative wake-up test is limited by patient tolerance, additional operative time, and a limited assessment of the neurologic status during the test only. Modern neurophysiologic monitoring provides the benefit of patient comfort with the indirect continuous assessment of neurologic status during surgery.

Deficiencies of Electrophysiologic Monitoring

SSEPs monitor sensory function that is transmitted through the posterior columns of the spinal cord,2,7,8 whereas the majority of pathologic compressive lesions are ventrally located. The posterior columns monitored by SSEPs are, therefore, positioned farthest from the operative site of all spinal tracts. In the days before this vulnerability was recognized, and before MEPs were widely available, failure to detect injury was reported.4,9,10

SSEPs monitor the dorsal column function within the spinal cord via stimulation of peripheral nerves in the arms and in the legs. False-negative and false-positive recordings have been reported. Although reported rates vary, a large series of 50,000 patients demonstrated a 0.067% false-negative rate.11 On average, the false-negative rate is reported to be less than 2%, and the false-positive rate is less than 3%.12–16

One must be aware of the technical limitations of SSEP to avoid misinterpretation. Securing both peripheral and central recording sites for the afferent volley helps differentiate technical failure from neurologic injury. A technical failure affects changes in the latencies or amplitude in both the peripheral and central recorded responses; neurologic injury affects only central responses. Moreover, following significant spinal cord injury, changes in SSEP signals may be delayed for up to 30 minutes.14

An undetermined fraction of monitoring errors results from unrecorded injury to the ventral spinal cord.17,18 Deformation of the ventral spinal cord may have a limited effect on dorsal column function, thereby accounting for the false-negative rate of SSEP. Monitoring with MEP enables the assessment of the ventral spinal cord and is associated with a shorter delay between injury and changes.

Transcranial electrical stimulation must overcome the resistance of the skull. As such, current requirements are higher and associated with a significant degree of discomfort in the awake state.19,20 Preinduction baseline recording of MEPs is therefore not possible.

Rationale for Nonparalytic Intraoperative Monitoring

The principal argument in favor of nonparalytic intraoperative monitoring revolves around the use of intraoperative observation of motor responses evoked by surgical manipulation as a monitoring technique. The point is made that the majority of surgical procedures during which electrodiagnostic monitoring might be beneficial involve neural decompression.21 The surgeon is able to directly observe the neural elements during the critical components of laminectomy and decompression, and this “direct observation” type of monitoring is, therefore, the most useful to the surgeon. For example, the observation of the dural sac and its relationship to surrounding and confining bony and soft tissue structures affords the skilled and alert surgeon the opportunity to monitor the extent of neural distortion and compression in real time. Some might argue that this is not so much monitoring as just careful surgical technique.

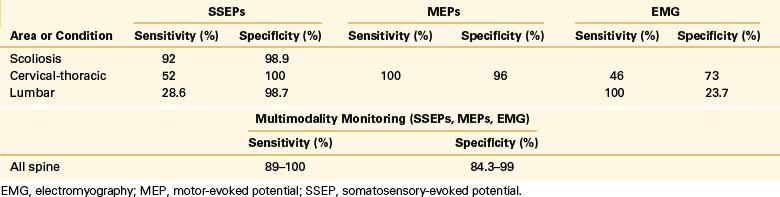

Using current electrodiagnostic monitoring methodologies, full paralysis is unnecessary, and almost any case can be carried out with some residual capacity for neural response. In these cases, inadvertent stimulation of a nerve root with a probe or cautery triggers a motor response that the surgeon will recognize immediately. Intrusion into the spinal canal or shift in spinal structures that impinge the cord itself still results in a sudden, profound total body “jump.” The surgical effort is reflexively stopped even before the monitoring personnel can sound a warning. With monitoring in place, however, the surgeon and staff can assess the clinical relevance of that “jump” and the possibility of injury and weigh the need for medical or further surgical treatment based on data as opposed to clinical suspicions (Table 179-1).

Lesser R.P., Raudzens P., Luders H., et al. Postoperative neurological deficits may occur despite unchanged intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:22-25.

Minahan R.E., Sepkuty J.P., Lesser R.P., et al. Anterior spinal cord injury with preserved neurogenic “motor” evoked potentials. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1442-1450.

Nuwer M.R., Dawson E.G., Carlson L.G., et al. Somatosensory evoked potential spinal cord monitoring reduces neurological deficits after scoliosis surgery: results of a large multicenter survey. EEG Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;96:6-11.

Powers S.K., Bolger C.A., Edwards M.S. Spinal cord pathways mediating somatosensory evoked potentials. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:472-482.

Vauzelle C., Stagnara P., Jouvinroux P. Functional monitoring of spinal cord activity during spinal surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;93:173-178.

1. Brown R.H., Nash C.L.Jr. Intra-operative spinal cord monitoring. In: Frymoyer J.W., editor. The adult spine: principles and practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1991:549.

2. Aminoff M.J. The use of somatosensory evoked potentials in the evaluation of the central nervous system. Neurol Clin. 1988;6:809-823.

3. Engler G.L., Spielholz N.I., Bernhard W.N., et al. Somatosensory evoked potentials during Harrington instrumentation for scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1978;60:528-532.

4. Lesser R.P., Raudzens P., Luders H., et al. Postoperative neurological deficits may occur despite unchanged intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:22-25.

5. Vauzelle C., Stagnara P., Jouvinroux P. Functional monitoring of spinal cord activity during spinal surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;93:173-178.

6. Minahan R.E., Sepkuty J.P., Lesser R.P., et al. Anterior spinal cord injury with preserved neurogenic ‘motor’ evoked potentials. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1442-1450.

7. Cusick J.F., Myklebust J., Larson S.J., et al. Spinal evoked potentials in the primate: neural substrate. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:551-557.

8. Powers S.K., Bolger C.A., Edwards M.S.B. Spinal cord pathways mediating somatosensory evoked potentials. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:472-482.

9. Ben-David B., Haller G., Taylor P. Anterior spinal fusion complicated by paraplegia: a case report of false-negative somatosensory evoked potential. Spine. 1987;12:536-539.

10. Ginsburg H.H., Shetter A.G., Raudzens P.A. Postoperative paraplegia with preserved intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials: case report. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:296-300.

11. Nuwer M.R., Dawson E.G., Carlson L.G., et al. Somatosensory evoked potential spinal cord monitoring reduces neurological deficits after scoliosis surgery: results of a large multicenter survey. EEG Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;96:6-11.

12. Dinner D.S., Luders H., Lesser R.P., et al. Intraoperative spinal somatosensory evoked potential monitoring. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:807-814.

13. Ginsburg H.H., Shetter A.G., Raudzens P.A. Postoperative paraplegia with preserved intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials: case report. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:296-300.

14. Grundy B.L. Monitoring of sensory evoked potentials during neurosurgical operations: methods and applications. Neurosurgery. 1982;11:556-575.

15. Jones S.J., Carter L., Edgar M.A., et al. Experience of epidural spinal cord monitoring in 410 cases. In: Schramm J., Jones S.J., editors. Spinal cord monitoring. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1985:215-220.

16. Lesser R.P., Raudzens P., Luders H., et al. Postoperative neurological deficits may occur despite unchanged intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:22-25.

17. American Electroencephalographic Society Evoked Potentials Committee. American Electroencephalographic Society guidelines for intraoperative monitoring of sensory evoked potentials. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1987;4:397-416.

18. Shimizu H., Shimoji K., Maruyama N., et al. Human spinal cord potentials produced in lumbosacral enlargement by descending volleys. J Neurophysiol. 1982;48:1108-1120.

19. Owen J.H., Laschinger J., Bridwell K., et al. Sensitivity and specificity of somatosensory and neurogenic-motor evoked potentials in animals and humans. Spine. 1988;13:1111-1118.

20. Tamaki T., Noguchi T., Takano H., et al. Spinal cord monitoring as a clinical utilization of spinal evoked potentials. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;185:58-64.

21. Sypert G. Stabilization procedures for thoracic and lumbar fractures. Clin Neurosurg. 1988;34:340-377.