CHAPTER 204 Intracranial Germ Cell Tumors

Intracranial germ cell tumors are a diverse group of lesions that are thought to arise from rests of primordial germ cells. Although collectively accounting for less than 4% of all brain tumors in most North American series, for reasons that are unclear, these lesions appear to be relatively more frequent in many Asian series.1,2 Because intracranial germ cell tumors characteristically arise in deep midline structures and can exhibit widely varying degrees of responsiveness to treatment depending on histology, management of these lesions poses a number of challenges, and many aspects in the care of patients with these tumors remain controversial. The current chapter reviews the classification of these tumors, diagnostic considerations, and therapeutic approaches, as well as discusses ongoing studies that are directed at refining the management of these lesions.

Classification and Epidemiology

Germ cell tumors can be categorized according to histology, location, and the presence or absence of dissemination. The World Health Organization histologic classification recognizes six subtypes (Table 204-1), although from a therapeutic standpoint these lesions are generally categorized as germinomas, nongerminomatous germ cell tumors (NGGCTs), and teratomas. The NGGCT group includes embryonal carcinoma, endodermal sinus (yolk sac) tumor, choriocarcinoma, and mixed tumors, which often also contain both germinomatous and teratomatous elements. Pure germinomas account for more than 50% of all germ cell tumors, mixed tumors and teratomas each account for 10% to 20%, and the remaining NGGCT subgroups each account for 5% to 10% of tumors.2–7 It has been suggested by Teilum that the individual histologic subsets reflect the transformation of different embryonic (e.g., germinoma, teratoma) and extraembryonic (e.g., NGGCT) cell rests.8 From this perspective, germinoma would theoretically reflect the most undifferentiated of the germ cell tumors, although contrary to the situation with other tumor types, they are the most treatment-responsive germ cell neoplasms. Because many tumors contain both germinomatous and nongerminomatous elements, the latter of which can adversely affect outcome, adequate tissue sampling and histologic assessment or evaluation of tumor markers or both, are essential in guiding therapy.

TABLE 204-1 World Health Organization Classification of Germ Cell Tumors

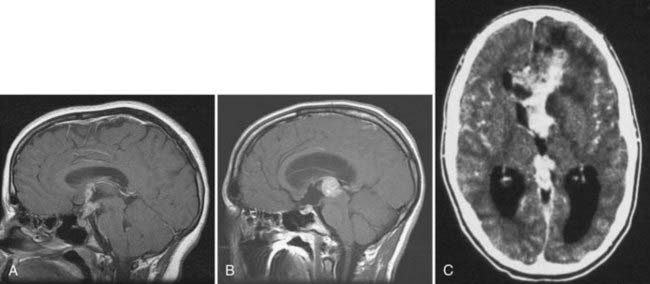

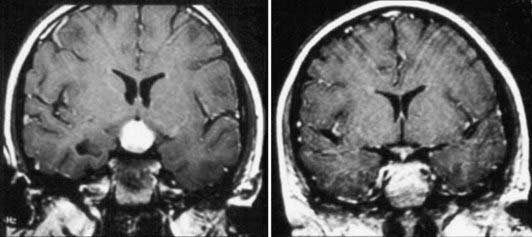

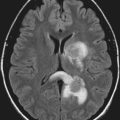

Germ cell tumors are also commonly categorized according to their site of origin, with the vast majority of lesions originating in the pineal or suprasellar regions (Fig. 204-1A and B).1,4,9 The former outnumber the latter by a ratio of 2 : 1,1,2 although this distribution is influenced by patient age and sex. Suprasellar tumors are more common in females than males, whereas pineal region tumors are overwhelmingly more common in males.1,7 Although germ cell tumors as a group are most frequently detected around the time of puberty or shortly thereafter,2 suprasellar lesions often occur earlier in childhood and more commonly contain nongerminomatous elements.3 In up to 10% of patients, tumor is simultaneously detected in both the pineal and suprasellar regions (Fig. 204-1C).1,2 It is unclear whether this represents bifocal tumor onset or metastatic spread from a single site. However, the frequent endoscopic detection of metastatic deposits within the third ventricular floor in patients with pineal region germinomas suggests that the latter explanation is more likely.10 In addition to the pineal and suprasellar regions, germ cell tumors have also been reported to arise in a number of atypical intracranial locations, including the basal ganglia and posterior fossa.1,9

Clinical Findings

Suprasellar lesions typically cause symptoms of hypothalamic-pituitary axis dysfunction,1,2,6,9 particularly diabetes insipidus, which is almost universally seen. Disturbances in visual acuity and visual fields are likewise common.1,11 Diabetes insipidus is also observed in a small percentage of patients who seem to have purely pineal lesions, possibly reflecting microscopic spread of tumor to the anterior third ventricular floor.1,2,10 Similarly, precocious puberty may be observed in patients with pineal as well as suprasellar lesions as a result of secretion of β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) by the tumor.

Because NGGCTs tend to be biologically more aggressive than germinomas, these lesions typically have a shorter natural history. In some patients with germinomas, the duration of symptoms before detection can be extremely protracted, with isolated diabetes insipidus occasionally being present for years before diagnosis.1,2,11,12 Germinomas arising in the basal ganglia or thalamus have also been reported to be accompanied by an extended interval of seizures, hemiparesis, and dementia before diagnosis.13 Among the NGGCTs, choriocarcinomas have a particular propensity to enlarge rapidly and undergo hemorrhage, thereby leading to a precipitous onset of symptoms and clinical deterioration.1,3

Germ cell tumors that arise in infancy and early childhood pose particular diagnostic challenges. Frequently, the sole initial sign is increased intracranial pressure manifested as macrocephaly, split sutures, and a bulging fontanelle.1,2,6 In some cases, the mode of manifestation can be even more nonspecific and consist of failure to thrive and loss of developmental milestones. Accordingly, such tumors are often extremely large at the time of diagnosis.14

Diagnostic Evaluation

Apart from teratomas, which can have a mixture of cystic and solid elements, frequently with fat and bone visible on imaging,15 most germ cell tumors can resemble other pineal region and suprasellar tumors radiologically. In the past, patients with lesions of the pineal and suprasellar regions that were thought to possibly be germ cell tumors were often given a “test dose” of irradiation, and if a complete response was achieved, the tumors were presumed to have been germinomas and treated empirically with additional radiotherapy, with biopsy reserved for nonresponding lesions.16 Because lesions other than germinomas may respond rapidly to irradiation but ultimately require different management approaches, this strategy has fallen out of favor. Accordingly, appropriate diagnostic evaluation incorporates a combination of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) marker analysis for α-fetoprotein (AFP) and β-hCG, and in patients lacking significant elevation of these markers, histologic examination of a biopsy sample is warranted.1,3,6,9

AFP is a marker for tumors with yolk sac components (endodermal sinus tumor, teratoma with endodermal sinus elements, and occasionally embryonal carcinoma), whereas β-hCG is commonly expressed by choriocarcinomas, malignant teratomas, and embryonal carcinomas containing trophoblastic tissue (Table 204-2). Expression of high levels of either AFP or β-hCG is diagnostic of an NGGCT, and histologic confirmation is not required. Low-level expression of β-hCG (<50 to 100 mIU/mL) is often observed in germinomas with syncytiotrophoblastic cells, and in this setting, some investigators will treat patients empirically as though they have a germinoma,17 although this approach remains controversial. In situations in which neither AFP nor β-hCG is elevated, biopsy is required to establish the diagnosis. Although germinomas can express placental alkaline phosphatase histologically, this marker has not proved widely useful for noninvasively establishing the diagnosis of germinoma by blood or CSF marker analysis.2,6,18 Similarly, soluble c-kit has been suggested as a CSF marker of germinomas,19 although the sensitivity and specificity of this marker have not been independently confirmed in the clinical diagnostic setting.

| β-hCG | AFP | |

|---|---|---|

| Teratoma | + | ±* |

| Germinoma (pure) | ±† | − |

| Choriocarcinoma | ++ | − |

| Mixed germ cell | ++ | ++ |

| Endodermal sinus (yolk sac) tumor | − | ++ |

| Embryonal carcinoma | ± | ± |

AFP, α-fetoprotein; β-hCG, β-human chorionic gonadotropin.

* Small amounts of AFP may be secreted by intestinal glandular components.

† Levels less than 50 to 100 mIU/ml may be secreted by syncytiotrophoblastic components.

Because germ cell tumors can disseminate within the neuraxis, staging by CSF cytology and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine also constitutes an important component of the diagnostic evaluation. The reported frequency of dissemination varies widely between studies. Even excluding patients with bifocal pineal and suprasellar lesions, at least 10% of patients have evidence of leptomeningeal or intraventricular tumor spread based on imaging, positive CSF cytology, or a combination of both.7,20

Surgical Management

The role of surgery in the management of germ cell tumors is principally determined by the underlying histologic diagnosis and location of the tumor. Tumors of the pineal region typically manifest with obstructive hydrocephalus, which often requires timely intervention for diversion of CSF. Historically, diversion was commonly accomplished by insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, which allowed prompt relief of the elevated pressure, as well as sampling of CSF for marker analysis. However, because obstruction of CSF pathways often resolves rapidly with treatment, particularly in patients with germinomas, and shunting places the patient at risk for shunt-related metastases,4,6,21 this approach has become less common as a primary management strategy.

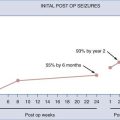

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy has emerged as a more popular alternative for CSF diversion in recent years because it allows biopsy in many cases, permits sampling of CSF for markers and cytologic examination, and achieves internal CSF diversion. This strategy for CSF management is not applicable in patients with significant involvement of the third ventricular floor by tumor, a situation that applies in most suprasellar germ cell tumors, and in such cases, shunt insertion remains a valuable option. A third approach to CSF diversion is temporary external ventricular drainage, which may be useful for patients with germinoma, in whom the tumor can regress significantly within days of beginning irradiation or chemotherapy (Fig. 204-2), and for situations in which open surgical resection is being considered as an initial component of management.

A second neurosurgical issue in initial management involves establishing a tissue diagnosis. For tumors that exhibit significantly elevated levels of AFP or β-hCG, the diagnosis of NGGCT is already established, thus obviating the need for tissue sampling. However, for pineal and suprasellar tumors of uncertain etiology that are presumed to be germ cell tumors, biopsy is warranted to confirm the diagnosis and define the histology. Acquisition of tissue can often be accomplished with stereotactic or endoscopic techniques, although in view of the risk for hemorrhage associated with these approaches, some neurosurgeons prefer to perform an open biopsy.15

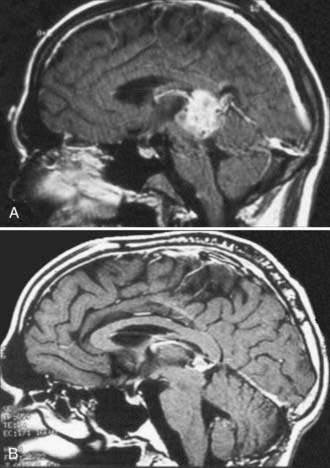

Because germinomas are extremely responsive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, there is usually no indication for surgical debulking.22 The situation is more complex for NGGCTs, which may contain treatment-resistant teratoma admixed with germinomatous and nongerminomatous elements (Fig. 204-3). Most recent cooperative group protocols have favored proceeding with initial adjuvant therapy in an effort to eradicate the malignant components of the tumor, with the understanding that in many cases a teratomatous remnant will remain and eventually require additional intervention. Thus, a second scenario in which resection may be appropriate relates to so-called second-look surgery for biopsy and resection of this residual tissue.1,2,9,23–28 Despite the lack of definitive evidence that this delayed approach improves survival, there is strong anecdotal evidence that it spares many children with treatment-responsive NGGCTs the risks associated with surgical intervention and, by eliminating the very aggressive components of the tumor and decreasing tumor size, may reduce the risk related to resection in patients with teratomatous elements who ultimately require surgical intervention.25–30 Management of patients with NGGCTs who continue to have elevated markers after initial adjuvant therapy remains controversial because this implies the existence of residual malignant elements, and in such cases, the benefit of second-look surgery remains uncertain.26

For patients who are appropriate candidates for tumor resection, options for the surgical approach and technical caveats are in large part influenced by the location and extent of the tumor. For lesions in the pineal region, supracerebellar infratentorial, suboccipital transtentorial, and interhemispheric transventricular approaches may each be appropriate, depending on whether the tumor predominantly extends above or below the vein of Galen and the degree to which the lesion fills the posterior third ventricle.15,31 Similarly, a variety of options are available for suprasellar lesions, including the pterional, subfrontal, anterior interhemispheric, and transventricular routes, as determined by the growth pattern of the tumor.32

Adjuvant Therapy and Prognostic Considerations

The strongest determinant of prognosis for patients with central nervous system (CNS) germ cell tumors is the histologic subtype of the tumor. Germinomas are extremely responsive to both radiation therapy and chemotherapy, with long-term survival rates in the range of 90% as long as radiation is included in the treatment.1,6,33 Although the presence of disseminated disease and elevated levels of β-hCG (a marker of syncytiotrophoblastic elements) have been found to be adverse prognostic features in some studies,33–35 other reports have noted that these factors do not preclude excellent survival rates in the setting of pure germinoma, provided that therapy is appropriately tailored.17,36 In contrast, outcome results for patients with nongerminomatous tumors have been much less favorable, with 5-year survival rates in the range of 40% to 70%, even with intensive multimodality therapy.1,2,6,9,33 Accordingly, the treatment strategies that have been used in recent years for these two subgroups of tumors have focused on reducing the morbidity of treatment and long-term sequelae in children with germinomas while maintaining excellent survival rates, and enhancing long-term disease control in children with NGGCTs.

Germinomas

Radiotherapy has historically been the treatment of choice for patients with germinomas, although doses and treatment volumes have varied widely between studies.1,2,4,6,33,37,38 Interpretation of institutional data has been complicated by the fact that subsets of patients have been treated empirically without histologic confirmation and staging evaluations have been inconsistently performed, which may influence the treatment fields.1,6,11,39 Consequently, conclusions regarding the choice of local versus whole ventricular, whole-brain, or craniospinal treatment fields remain controversial, as does the dose that should be administered to the primary tumor site.1,39–41

In general, older studies have reported the use of primary site radiation doses of approximately 5000 cGy.42–50 Although some reports have noted lower rates of disease control with radiation doses less than 4000 cGy,1,49 several studies have suggested that doses in the range of 4000 to 4500 cGy achieve survival results comparable to those achieved with higher doses.41,51,52 The multicenter Maligue Keimzelltümoren (MAKEI) series of prospective trials confirmed progression-free survival rates in excess of 90% with craniospinal radiation doses of 3000 cGy supplemented with a boost dose of 1500 cGy to the primary site,41 which provided a strong rationale for using these lower doses in subsequent studies.

Achieving a consensus for lowering treatment volumes has been much more problematic. Although anecdotal reports have also noted high rates of disease control with local treatment alone if there is no evidence of disease spread,48,53,54 some studies have observed an unacceptably high rate of failure outside the treatment volume with involved field therapy.49 Because progression-free survival rates as high as 97% have been achieved with the use of craniospinal fields,1 even in patients with known disease dissemination, there has been substantial support for the use of craniospinal irradiation for these tumors.

Although craniospinal irradiation clearly results in outstanding rates of disease control, there is concern that children who have received these doses of radiotherapy to the whole brain or craniospinal axis have a significant risk for long-term cognitive and endocrine sequelae,55,56 as well as an increased risk for radiation-related second malignancies. In view of these risks, there has been interest in evaluating treatment strategies to safely reduce the dose and volume of radiotherapy. Some radiation oncologists have favored the use of whole ventricular fields, which reduces the dose to the cortex, an uncommon site of tumor recurrence.38 Because chemotherapy with agents such as cisplatin, carboplatin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and bleomycin has been the mainstay of treatment of non-CNS germinomas,57,58 several studies have examined the use of this modality as a way to further reduce the treatment fields in children with CNS lesions.

Based on the documented activity of these agents in several pilot studies for patients with recurrent CNS germinomas,59–61 a series of studies examined the feasibility of using preirradiation chemotherapy to reduce the dose and volume of radiotherapy. Almost uniformly, the response rate to chemotherapy is quite high. For example, Allen and colleagues achieved complete responses in 10 of 11 patients treated with preirradiation cyclophosphamide and in 7 of 10 treated with carboplatin. For patients who had a complete response, the involved field dose was reduced from 5000 to 3000 cGy for those with localized disease and the craniospinal dose from 3600 to 2100 cGy for those with disseminated disease.62 Sawamura and coauthors also reported excellent response rates in patients with germinoma treated with cisplatin and etoposide, followed by 2400 cGy to the involved field.23 Excellent disease control was achieved with the addition of ifosfamide to this regimen in patients with potentially adverse features, such as elevated β-hCG or multifocal disease, the latter of whom also received reduced-dose (2400 cGy) craniospinal irradiation. All 17 patients in this series had a complete response to chemotherapy, and 16 (94%) were progression free at a median follow-up of 24 months.23 Similarly, a phase II study by the Pediatric Oncology Group (P9530) showed objective radiologic responses in 10 of 11 evaluable patients after chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide, alternating with cyclophosphamide and vincristine, and a 100% survival rate after response-based radiation therapy, in which patients with localized germinomas who achieved a complete response received local irradiation to a dose of 3060 cGy, those with incomplete responses received 5400 cGy, and those with multicentric or disseminated disease received additional craniospinal irradiation.63

With such excellent response data, the possibility of using chemotherapy alone to treat patients with germinoma was also explored. The First International Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumor Study Group trial used four cycles of carboplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin to treat 45 patients with germinoma.25 Those with a complete response received two further cycles, without irradiation. Although the initial response rates to chemotherapy were excellent, relapse occurred in 22 of 45 germinoma patients, the vast majority of whom were ultimately salvaged, albeit with the use of more intensive chemotherapy or craniospinal irradiation, or both.64 In addition, the mortality rate of the treatment itself was 10%, which highlights the difficulty of administering chemotherapy to patients with diabetes insipidus or panhypopituitarism. Thus, although half the patients were treated successfully with chemotherapy alone, the overall results were inferior to those achieved with radiation therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

Taken together, the aforementioned studies suggest that radiation therapy doses and fields may be reduced, but not eliminated, by the administration of chemotherapy. A series of studies have therefore further explored the concept of chemotherapy and reduced-dose/volume irradiation to identify factors associated with disease control.61,65–70 A large study by the French Society of Pediatric Oncology (SFOP), in which preirradiation chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin, alternating with etoposide and ifosfamide, was followed by local radiation doses of 4000 cGy with 2-cm margins, achieved a 3-year event-free survival rate of 96.4%.36 However, 3 of the 4 patients who experienced relapse had disease recurrence outside the radiation treatment volume, and two of the recurrences occurred more than 3 years after diagnosis. Similarly, a cooperative group trial of the Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group noted a 12% recurrence rate after treatment with etoposide and either carboplatin or cisplatin followed by 2400-cGy local irradiation to the tumor plus a 1-cm margin, with seven of nine recurrences occurring outside the radiation treatment volume.65 Longer follow-up for both these studies has been presented and published in abstract form. In the SFOP study, the 8-year event-free survival rate had fallen to 83%, with 8 of 10 patients failing at the margin or outside the involved field.68 Follow-up of the Japanese study showed a 28% recurrence rate in patients treated with involved field irradiation versus 0% in those treated with whole-brain irradiation and 6% in those treated with extended field radiotherapy.69 These results corroborate smaller published series from the United States reporting a higher incidence of ventricular relapses in patients receiving focal irradiation.70

In this regard, the increasingly widespread use of neuroendoscopy for biopsy of germ cell tumors and CSF diversion has confirmed that even high-resolution MRI may underestimate the true extent of disease spread. In a subset of cases, lesions that appear to be localized on MRI have been observed to have microscopic nodules of tumor studding the ventricular surface,10 which may in part account for the failure of local fields with narrow margins to achieve disease control.

End points of the study included not only event-free survival and patterns of recurrence but also health-related quality of life and cognitive function to determine whether the reduction in radiation therapy produced the expected improvements in functional outcome.71 Unfortunately, completion of this randomized study was precluded by slow enrollment, and a nonrandomized study is under development to address some of its proposed objectives.

Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors

In contrast to the excellent results achieved with irradiation alone in children with germinomas, the outcome is substantially less favorable in patients with NGGCTs, with long-term survival rates of less than 40%.1,2,6,9,33,72 As with germinomas, there has been substantial variation in the radiation doses that have been used in individual studies. Rates of disease control have been reported to be lower with local field doses of less than 4500 cGy than with higher doses,73 and in the MAKEI series of studies, disease control rates were lower with the use of local than with whole-brain or craniospinal treatment volumes.41 However, different histologic subtypes of NGGCTs may differ widely in their sensitivity to irradiation. A review by Matsutani and associates noted that histologically confirmed endodermal sinus tumors, choriocarcinomas, and embryonal carcinomas had survival rates in the range of 25% and mixed malignant tumors had an even worse outcome but that tumors with a predominant germinomatous component admixed with teratomatous or NGGCT elements had a substantially better outcome,6 thus suggesting that the optimal management of these tumors may require treatment stratification based on histologic or marker status.6

However, even among the “favorable” subsets of NGGCTs, overall survival is substantially worse than for germinomas. Because systemic NGGCTs respond well to various combinations of carboplatin, cisplatin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, and bleomycin, interest has been directed at evaluating these agents for the treatment of CNS NGGCTs.74–82 Robertson and coauthors reported favorable results in 18 patients with newly diagnosed intracranial NGGCT who received four courses of cisplatin/etoposide followed by radiation therapy and additional chemotherapy with etoposide, bleomycin, and vinblastine.80 Of 12 patients evaluable for response, 5 had complete responses and 4 had partial responses to the neoadjuvant regimen; 4-year progression-free and overall survival rates were 67% and 74%, respectively.80 In the MAKEI 89 study, two cycles of preirradiation cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin were given to 14 patients with NGGCT, followed by postirradiation ifosfamide, cisplatin, and vinblastine; the 5-year survival rate was 80%.66 Similarly favorable results were obtained in several other recent studies, including an SFOP trial involving 27 patients.24,82 Of particular interest, in all 14 patients who underwent second-look surgery for residual abnormalities detected on MRI before irradiation, only mature teratoma or fibrosis was seen on histologic examination. At a median follow-up of 53 months, 20 of 27 patients were alive and only 8 had relapsed.24 Likewise, in the Pediatric Oncology Group P9530 study involving cycles of cisplatin and etoposide alternating with cyclophosphamide and vincristine before craniospinal irradiation, 2 of 9 evaluable NGGCT patients achieved a complete response and 3 had partial responses before irradiation. Of the overall study cohort, which included 4 patients who were not evaluable for response after having undergone tumor resection and 1 other who did not complete chemotherapy before irradiation, 11 of 14 were progression-free survivors at a median follow-up of 58 months.63

As noted for germinomas, chemotherapy has not eliminated the need for irradiation in patients with intracranial NGGCTs.25,83 In the First International Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumor Study Group trial, four cycles of carboplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin were administered to 26 patients with NGGCTs. Patients who achieved a complete response received two additional cycles of chemotherapy, whereas those with less than a complete response underwent irradiation, either before or after two additional cycles of the aforementioned chemotherapy plus cyclophosphamide. Although 21 patients achieved complete remission after the first four cycles of therapy, subsequent disease progression was noted in 13 of 26 patients, and a toxic death rate of 10% was observed.25 The Second International CNS Germ Cell Study Group trial modified the chemotherapy regimen by adding cisplatin and high-dose cyclophosphamide. Only 8 of 20 patients remained progression free, for a 5-year event-free survival rate of just 36%, with 3 of the 8 having received radiation therapy in violation of the protocol,83 results that remain inferior to those reported with multimodality therapy. Similarly, Calaminus and colleagues reviewed the data from several European intracranial NGGCT studies and noted that 9 of 11 patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy without irradiation died of their disease whereas 20 of 27 treated with similar chemotherapy and radiotherapy were disease free 4 years after diagnosis.66

Although it appears that a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is necessary to achieve optimal survival results in children with NGGCT, it remains to be determined whether administration of chemotherapy allows any modification in the radiation doses and fields needed for control of disease. It is generally agreed that craniospinal irradiation should be given when metastases are present at diagnosis, although the appropriate treatment fields for patients with localized disease remains controversial. The recent SFOP studies noted favorable results with induction chemotherapy in conjunction with 5500-cGy focal radiotherapy.82 However, a study by Robertson and coworkers, which used a similar chemotherapy regimen, reported that 4 of 13 patients with localized disease who received involved field irradiation with chemotherapy experienced relapses outside the irradiation field.80 In contrast, Calaminus and coauthors reported an 80% 5-year progression-free survival rate in 14 patients treated with chemotherapy and craniospinal radiotherapy,66 thus suggesting a possible benefit with the use of craniospinal fields.

In an effort to enhance disease control in patients who did not achieve a complete or partial response, a preirradiation course of myeloablative chemotherapy with etoposide and thiotepa, followed by autologous stem cell rescue, was incorporated, an approach that has shown curative potential for high-risk or recurrent extracranial germ cell tumors,84–87 as well as a high rate of disease control in an SFOP pilot study for recurrent CNS germ cell tumors88 and in several other recent reports.64,89–91 On completion of chemotherapy, all patients receive 3600-cGy craniospinal irradiation with a boost to the primary tumor sites up to a total dose of 5400 cGy. The primary objective of the statistical analysis will be to estimate the response rate of NGGCT to induction chemotherapy. Secondary objectives will include estimating rates of event-free and overall survival and key toxicities, correlating marker levels with response, and evaluating the response to high-dose chemotherapy in patients with disease refractory to induction therapy.

Allen JC, DaRosso RC, Donahue B, et al. A phase II trial of preirradiation carboplatin in newly diagnosed germinoma of the central nervous system. Cancer. 1994;74:940-944.

Aoyama H, Shirato H, Ikeda J, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by low-dose involved-field radiotherapy for intracranial germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:857-865.

Balmaceda C, Heller G, Rosenblum M, et al. Chemotherapy without irradiation—a novel approach for newly diagnosed CNS germ cell tumors: results of an international cooperative trial. The First International Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumor Study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2908-2915.

Bamberg M, Kortman RD, Calaminus G, et al. Radiation therapy for intracranial germinoma: results of the German cooperative prospective trials MAKEI 83/86/89. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2585-2592.

Baranzelli MC, Patte C, Bouffet E, et al. An attempt to treat pediatric intracranial αFP and βHCG-secreting germ cell tumors with chemotherapy alone. SFOP experience with 18 cases. Society Francaise d-Oncologie Pediatrique. J Neurooncol. 1998;37:229-239.

Baranzelli MC, Patte C, Bouffet E, et al. Non-metastatic intracranial germinomas. The experience of the French Society of Pediatric Oncology. Cancer. 1997;80:1792-1797.

Bouffet E, Baranzelli MC, Patte C, et al. Combined treatment modality for intracranial germinomas: results of a multicentre SFOP experience. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1199-1204.

Calaminus G, Bamberg M, Baranzelli MC, et al. Intracranial germ cell tumors: a comprehensive update of the European data. Neuropediatrics. 1994;25:26-31.

Haddock MG, Schild SE, Scheithauer BW, et al. Radiation therapy for histologically confirmed primary central nervous system germinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:915-923.

Jennings MT, Gelman R, Hochberg F. Intracranial germ-cell tumors: natural history and pathogenesis. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:155-167.

Jubran RF, Finlay J. Central nervous system germ cell tumors: controversies in diagnosis and treatment. Oncology. 2005;19:705-711.

Kobayashi T, Yoshida J, Ishiyama J, et al. Combination chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide for malignant intracranial germ cell tumors. An experimental and clinical study. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:676-681.

Kretschmar C, Kleinberg L, Greenberg M, et al. Pre-radiation chemotherapy with response-based radiation therapy in children with central nervous system germ cell tumors: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;48:285-291.

Matsutani M. Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group. Combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy for CNS germ cell tumors—the Japanese experience. J Neurooncol. 2001;54:311-316.

Matsutani M, Sano K, Takakura K, et al. Primary intracranial germ cell tumors: a clinical analysis of 153 histologically verified cases. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:446-455.

Packer RJ, Cohen BH, Coney K. Intracranial germ cell tumors. Oncologist. 2000;5:312-320.

Robertson PL, DaRosso RC, Allen JC. Improved prognosis of intracranial non-germinoma germ cell tumors with multimodality therapy. J Neurooncol. 1997;32:71-80.

Sawamura Y, de Tribolet N, Ishii N, et al. Management of primary intracranial germinomas: diagnostic surgery or radical resection? J Neurosurg. 1997;87:262-266.

Sawamura Y, Ikeda J, Shirato H, et al. Germ cell tumours of the central nervous system: treatment consideration based on 111 cases and their long-term outcomes. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:104-110.

Sawamura Y, Shirato H, Ikeda J, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by reduced-volume radiation therapy for newly diagnosed central nervous system germinoma. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:66-72.

Shibamoto Y, Takahashi M, Sasai K. Prognosis of intracranial germinoma with synctiotrophoblastic giant cells treated with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:505-510.

Tomita T. Pineal region tumors. In: Albright AL, Pollack IF, Adelson PD, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Neurosurgery. New York: Thieme; 2008:585-605.

Tomita T. Midline intraaxial neoplasms. In: Albright AL, Pollack IF, Adelson PD, editors. Operative Techniques In Pediatric Neurosurgery. New York: Thieme; 2001:147-161.

Weiner HL, Lichtenbaum RA, Wisoff JH, et al. Delayed surgical resection of central nervous system germ cell tumors. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:727-734.

Wellons JC3rd, Reddy AT, Tubbs RS, et al. Neuroendoscopic findings in patients with intracranial germinomas correlating with diabetes insipidus. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2004;100:430-436.

1 Packer RJ, Cohen BH, Coney K. Intracranial germ cell tumors. Oncologist. 2000;5:312-320.

2 Jennings MT, Gelman R, Hochberg F. Intracranial germ-cell tumors: Natural history and pathogenesis. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:155-167.

3 Sano K. Pathogenesis of intracranial germ cell tumors reconsidered. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:258-264.

4 Hoffman HJ, Yoshida M, Becker LE, et al. Pineal region tumors in childhood: experience at the Hospital for Sick Children, 1983. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21:91-103.

5 Horowitz MB, Hall WA. Central nervous system germinomas: a review. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:652-657.

6 Matsutani M, Sano K, Takakura K, et al. Primary intracranial germ cell tumors: a clinical analysis of 153 histologically verified cases. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:446-455.

7 Keene D, Johnston D, Strother D, et al. Epidemiological survey of central nervous system germ cell tumors in Canadian children. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:289-295.

8 Teilum G. Special Tumors of the Ovary and Testis and Related Extragonadal Lesions. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1976.

9 Jubran RF, Finlay J. Central nervous system germ cell tumors: controversies in diagnosis and treatment. Oncology. 2005;19:705-711.

10 Wellons JC3rd, Reddy AT, Tubbs RS, et al. Neuroendoscopic findings in patients with intracranial germinomas correlating with diabetes insipidus. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2004;100:430-436.

11 Kretschmar CS. Germ cell tumors of the brain in children: a review of current literature and new advances in therapy. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:187-198.

12 Maghnie M, Cosi G, Genovese E, et al. Central diabetes insipidus in children and young adults. N Eng J Med. 2000;343:998-1007.

13 Ozelame RV, Shroff M, Wood B, et al. Basal ganglia germinoma in children with associated ipsilateral cerebral and brain stem hemiatrophy. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:325-330.

14 Souweidane MM. Brain tumors in the first two years of life. In: Albright AL, Pollack IF, Adelson PD, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Neurosurgery. New York: Thieme; 2008:489-510.

15 Tomita T. Pineal region tumors. In: Albright AL, Pollack IF, Adelson PD, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Neurosurgery. New York: Thieme; 2008:585-605.

16 Nakagawa K, Yukimasa A, Akanuma A, et al. Radiation therapy of intracranial germ-cell tumors with radiosensitivity assessment. Radiat Med. 1992;10:55-61.

17 Shibamoto Y, Takahashi M, Sasai K. Prognosis of intracranial germinoma with syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells treated with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:505-510.

18 Shinoda J, Yamada H, Sakai N, et al. Placental alkaline phosphatase as a tumor marker for primary intracranial germinoma. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:710-720.

19 Miyanohara O, Takeshima H, Kaji M, et al. Diagnostic significance of soluble c-kit in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with germ cell tumors. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:177-183.

20 Shibamoto Y, Oda Y, Yamashita J, et al. The role of cerebrospinal fluid cytology in radiotherapy planning for intracranial germinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;27:1089-1094.

21 Rickert CH. Abdominal metastases of pediatric brain tumors via ventriculoperitoneal shunts. Childs Nerv Syst. 1998;14:10-14.

22 Sawamura Y, de Tribolet N, Ishii N, et al. Management of primary intracranial germinomas: diagnostic surgery or radical resection? J Neurosurg. 1997;87:262-266.

23 Sawamura Y, Shirato H, Ikeda J, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by reduced-volume radiation therapy for newly diagnosed central nervous system germinoma. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:66-72.

24 Baranzelli MC, Patte C, Bouffet E, et al. Carboplatin-based chemotherapy (CT) and focal irradiation (RT) in primary cerebral germ cell tumors (GCT): A French Society of Pediatric Oncology (SFOP) experience. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1999;18:140A.

25 Balmaceda C, Heller G, Rosenblum M, et al. Chemotherapy without irradiation—a novel approach for newly diagnosed CNS germ cell tumors: results of an international cooperative trial. The First International Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumor Study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2908-2915.

26 Weiner HL, Lichtenbaum RA, Wisoff JH, et al. Delayed surgical resection of central nervous system germ cell tumors. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:727-734.

27 Sawamura Y, Kato T, Ikeda J, et al. Teratomas of the central nervous system: treatment considerations based on 34 cases. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:728-737.

28 Baranzelli MC, Patte C, Bouffet E, et al. Non-metastatic intracranial germinomas. The experience of the French Society of Pediatric Oncology. Cancer. 1997;80:1792-1797.

29 Knappe UJ, Bentele K, Horstmann M, et al. Treatment and long-term outcome of pineal nongerminomatous germ cell tumors. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1998;28:241-245.

30 Herrmann HD, Westphal M, Winkler K, et al. Treatment of nongerminomatous germ-cell tumors of the pineal region. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:524-529.

31 Bruce JN. Supracerebellar approach to pineal region lesions. In: Sekhar LN, Fessler RG, editors. Atlas of Neurosurgical Techniques. New York: Thieme; 2006:549-555.

32 Tomita T. Midline intraaxial neoplasms. In: Albright AL, Pollack IF, Adelson PD, editors. Operative Techniques In Pediatric Neurosurgery. New York: Thieme; 2001:147-161.

33 Sawamura Y, Ikeda J, Shirato H, et al. Germ cell tumours of the central nervous system: treatment consideration based on 111 cases and their long-term outcomes. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:104-110.

34 Inamura T, Nishio S, Ikezaki K, et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin in CSF, not serum, predicts outcome in germinoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:654-657.

35 Aoyama H, Shirato H, Ikeda J, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by low-dose involved-field radiotherapy for intracranial germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:857-865.

36 Bouffet E, Baranzelli MC, Patte C, et al. Combined treatment modality for intracranial germinomas: results of a multicentre SFOP experience. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1199-1204.

37 Merchant TE, Sherwood SH, Mulhern RK, et al. CNS germinoma: disease control and long-term functional outcome for 12 children treated with craniospinal irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:1171-1176.

38 Roberge D, Kun LE, Freeman CR. Intracranial germinoma: on whole-ventricular irradiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:358-362.

39 Hardenbergh PH, Golden J, Billet A, et al. Intracranial germinoma: the case for lower dose radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:419-426.

40 Wolden SL, Wara WM, Larson DA, et al. Radiation therapy for primary intracranial germ-cell tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:943-949.

41 Bamberg M, Kortman RD, Calaminus G, et al. Radiation therapy for intracranial germinoma: results of the German cooperative prospective trials MAKEI 83/86/89. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2585-2592.

42 Jenkin D, Berry M, Chan H. Pineal region germinomas in childhood: treatment considerations. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;18:541-545.

43 Sung DI, Harisiadis L, Chang CH. Midline pineal tumors and suprasellar germinomas: highly curable by irradiation. Radiology. 1978;128:745-751.

44 Wara WM, Jenkin RDT, Evans A, et al. Tumors of the pineal and suprasellar region: Children’s Cancer Study Group treatment results 1960-1975. Cancer. 1979;43:698-701.

45 Rao YTR, Medini E, Haselow RE, et al. Pineal and ectopic pineal tumors: the role of radiation therapy. Cancer. 1981;48:708-713.

46 Sano K, Matsutani M. Pinealoma (germinoma) treated by direct surgery and post-operative irradiation. Childs Brain. 1981;8:81-97.

47 Fields JN, Fulling KH, Thomas PRM, et al. Suprasellar germinoma: radiation therapy. Radiology. 1987;164:247-249.

48 Shibamoto Y, Abe M, Yamashita J, et al. Treatment results of intracranial germinoma as a function of the irradiated volume. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15:285-290.

49 Haddock MG, Schild SE, Scheithauer BW, et al. Radiation therapy for histologically confirmed primary central nervous system germinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:915-923.

50 Huh SE, Shin KH, Kim IH, et al. Radiotherapy of intracranial germinomas. Radiother Oncol. 1996;38:19-23.

51 Aoyama H, Shirato H, Kakuto Y, et al. Pathologically-proven intracranial germinoma treated with radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 1998;47:201-205.

52 Shibamoto Y, Takahashi M, Abe M, et al. Reduction of radiation dose for intracranial germinoma: a prospective study. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:984-989.

53 Linstadt D, Wara WM, Edwards MS, et al. Radiotherapy of primary intracranial germinomas: the case against routine craniospinal irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15:291-297.

54 Chao CK, Lee ST, Lin FJ, et al. A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in management of pineal tumor. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27:1185-1191.

55 Radcliffe J, Packer RJ, Atkins TE, et al. Three- and four-year cognitive outcome in children with noncortical brain tumors treated with whole-brain radiotherapy. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:551-554.

56 Ellenberg L, McComb JG, Siegel SE, Stowe S. Factors affecting intellectual outcome in pediatric brain tumor patients. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:638-644.

57 Peckham MJ, Horwich A, Hendry WF. Advanced seminoma: treatment with cis-platinum–based combination chemotherapy or carboplatin (JM8). Br J Cancer. 1985;52:7-13.

58 Bajorin DF, Sarosdy MF, Pfister DG, et al. Randomized trial of etoposide and cisplatin versus etoposide and carboplatin in patients with good-risk germ cell tumors: a multiinstitutional study. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:598-606.

59 Edwards MS, Hudgins RJ, Wilson CB, et al. Pineal region tumors in children. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:689-697.

60 Allen JC, Bosl G, Walker R. Chemotherapy trials in recurrent primary intracranial germ cell tumors. J Neurooncol. 1985;3:147-152.

61 Allen J, Siffert J, Velasquez L, et al. Review of contemporary North American clinical trials in primary CNS germinoma. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:517-518.

62 Allen JC, DaRosso RC, Donahue B, et al. A phase II trial of preirradiation carboplatin in newly diagnosed germinoma of the central nervous system. Cancer. 1994;74:940-944.

63 Kretschmar C, Kleinberg L, Greenberg M, et al. Pre-radiation chemotherapy with response-based radiation therapy in children with central nervous system germ cell tumors: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;48:285-291.

64 Merchant TE, Davis BJ, Sheldon JM, et al. Radiation therapy for relapsed CNS germinoma after primary chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:204-209.

65 Matsutani M. Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group. Combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy for CNS germ cell tumors—the Japanese experience. J Neurooncol. 2001;54:311-316.

66 Calaminus G, Bamberg M, Baranzelli MC, et al. Intracranial germ cell tumors: a comprehensive update of the European data. Neuropediatrics. 1994;25:26-31.

67 Buckner JC, Peethambaram PP, Smithson WA, et al. Phase II trial of primary chemotherapy followed by reduced-dose radiation for CNS germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:933-940.

68 Alepetite C, Patte C, Frappaz D, et al. Long-term follow-up of intracranial germinoma treated with primary chemotherapy followed by focal radiation treatment. The SFOP-90 experience. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:517.

69 Matsutani M. Treatment for intracranial germinoma: final results of the Japanese Study Group. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:519.

70 Douglas JG, Rockhill JK, Olson JM, et al. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy followed by focal reduced dose irradiation for pediatric primary central nervous system germinomas. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28:36-39.

71 Sutton LN, Radcliffe J, Goldwein JW, et al. Quality of life of adult survivors of germinomas treated with craniospinal irradiation. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:1292-1297.

72 Fuller BG, Kapp DS, Cox R. Radiation therapy of pineal region tumors: 25 new cases and a review of 208 previously reported cases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;28:229-245.

73 Borg M. Germ cell tumors of the central nervous system in children: controversies in radiotherapy. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40:367-374.

74 Kida Y, Kobayashi T, Yoshida J, et al. Chemotherapy with cisplatin for AFP secreting germ-cell tumor of the central nervous system. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:470-475.

75 Itoyama Y, Kochi M, Kuratsu J, et al. Treatment of intracranial nongerminomatous malignant germ cell tumors producing alpha fetoprotein. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:459-464.

76 Patel SR, Buckner JC, Smithson WA, et al. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy in primary central nervous system germ cell tumors. J Neurooncol. 1992;12:47-52.

77 Chang TK, Wong TT, Hwang B. Combination chemotherapy with vinblastine, bleomycin, cisplatin, and etoposide (VBPE) in children with primary intracranial germ cell tumors. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1995;24:358-372.

78 Kobayashi T, Yoshida J, Ishiyama J, et al. Combination chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide for malignant intracranial germ cell tumors. An experimental and clinical study. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:676-681.

79 Yoshida J, Sugita K, Kobayashi T, et al. Prognosis of intracranial germ cell tumors: effectiveness of chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide (CDDP and VP-16). Acta Neurochir (Wein). 1993;120:111-117.

80 Robertson PL, DaRosso RC, Allen JC. Improved prognosis of intracranial non-germinoma germ cell tumors with multimodality therapy. J Neurooncol. 1997;32:71-80.

81 Calaminus G, Koch S, Frappaz D, et al. Markers in serum/cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in non-germinomatous CNS germ cell tumors (GCT): implication of site and dissemination. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:469.

82 Baranzelli MC, Patte C, Bouffet E, et al. An attempt to treat pediatric intracranial αFP and βHCG-secreting germ cell tumors with chemotherapy alone. SFOP experience with 18 cases. Society Francaise d-Oncologie Pediatrique. J Neurooncol. 1998;37:229-239.

83 Kellie SJ, Boyce H, Dunkel IJ, et al. Primary chemotherapy for intracranial nongerminomatous germ cell tumors: results of the Second International CNS Germ Cell Study Group protocol. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:846-853.

84 Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bosl GJ, et al. High-dose carboplatin, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide for patients with refractory germ cell tumors: treatment results and prognostic factors for survival. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1098-1105.

85 Seigert W, Beyer J, Strohscheer I, et al. High-dose treatment with carboplatin etoposide and ifosfamide followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in refractory germ cell cancer—a phase I/II study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1223-1231.

86 Beyer J, Kramar R, Mandanas W, et al. High-dose chemotherapy as salvage treatment in germ cell tumors: a multivariate analysis of prognostic variables. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2638-2645.

87 Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bosl GJ, et al. High-dose carboplatin, etoposide and cyclophosphamide with autologous bone marrow transplantation in first-line therapy for patients with poor-risk germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2546-2552.

88 Bouffet B, Baranzelli C, Patte D, et al. High dose etoposide and thiotepa for refractory and recurrent malignant intracranial germ cell tumors. No. 38, 9th International Symposium in Pediatric Neuro-Oncology, June 11-14, 2000, San Francisco.

89 Modak S, Gardner S, Dunkel I, et al. Thiotepa-based high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue in patients with recurrent or progressive CNS germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1934-1943.

90 Mahoney DHJr, Strother D, Camitta B, et al. High-dose melphalan and cyclophosphamide with autologous bone marrow rescue for recurrent/progressive malignant brain tumors in children: a pilot Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:382-388.

91 Kadota RP, Mahoney DH, Doyle J, et al. Cyclophosphamide (CPM) and melphalan (MEL) for recurrent medulloblastoma (MB) and intracranial germinoma (GCT): a Children’s Oncology Group study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:422.