Chapter 331 Intestinal Transplantation in Children with Intestinal Failure

Indications for Intestinal Transplant

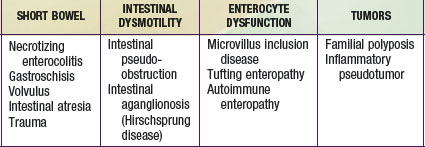

Intestinal failure (IF) describes a patient who has lost the ability to maintain nutritional support with his or her intestine and is permanently dependent on total parenteral nutrition (TPN). The majority of these patients have short bowels as a result of a congenital deficiency or acquired condition (Chapter 330.7). In others, the cause of IF is a functional disorder of motility or absorption (Table 331-1). Rarely do patients receive intestinal transplants for benign neoplasms. IF is a syndrome that includes “satellite” complications such as loss of venous access, life-threatening infections, and TPN-induced cholestatic liver disease. Patients who develop these complications have a ∼70% 1 yr mortality and thus require organ replacement therapy with intestinal transplantation.

Transplant Operation

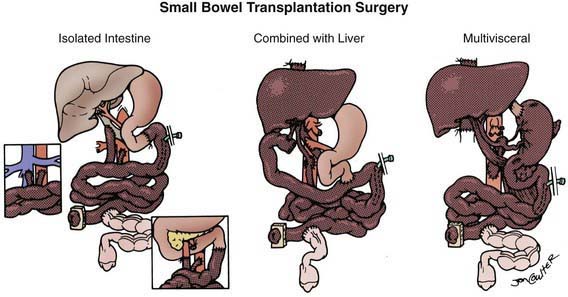

Types of Intestinal Grafts

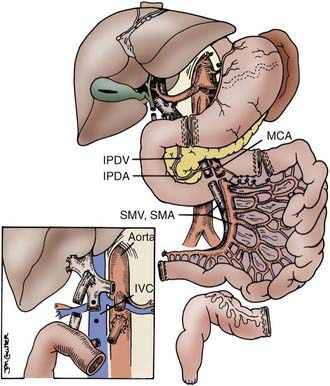

The procurement of these various types of grafts focuses on the preservation of the arterial vessels of celiac and/or superior mesenteric arteries, as well as appropriate venous outflow, which would include the superior mesenteric vein or the hepatic veins in the composite grafts. The various etiologies precipitating intestinal failure have prompted the development of these various combinations of intestinal allografts, where the component organs can be removed or retained according to the clinical needs of the individual patient. The larger composite grafts inherently retain the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries; this includes multivisceral grafts, liver plus small bowel grafts, and modified multivisceral grafts in which the liver is excluded but the entire gastrointestinal tract is replaced, including stomach. The isolated intestine graft retains the superior mesenteric artery and vein; this graft can be accomplished with preservation of the vessels going to the pancreas, when that organ has been allocated to another recipient. The graft that is to be used in a particular recipient is dissected out in situ and then removed after cardiac arrest of the donor, with core cooling of the organs, using an infusion of preservation solution (Fig. 331-1).

Postoperative Management

Infections

The most common infections after intestinal transplantation occur as a result of the continuing need for venous catheter placement for as long as 1 yr after transplant. Infections as a consequence of immunosuppressive drug management are due to cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection (22% incidence), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-induced infections (21% incidence), and adenovirus enteritis (40% incidence). Successful management of these viral infections is achieved through early detection and preemptive therapy, for both CMV and EBV, before the development of a serious life-threatening infection. This approach has improved outcomes for CMV, eliminating the mortality in the pediatric patient population (Chapters 171, 246, and 247).

Abu-Elmagd K, Fung J, Bueno J, et al. Logistics and technique for procurement of intestinal, pancreatic and hepatic grafts from the same donor. Ann Surg. 2000;232:680-697.

Berg CL, Steffick DE, Edwards EB, et al. Liver and intestine transplantation in the United States 1998–2007. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(Part 2):907-931.

Bond G, Reyes J, Mazariegos G, et al. The impact of positive T-cell lymphocytotoxic crossmatch on intestinal allograft rejection and survival. Transplant Proc. 2000;32:1197-1198.

Fishbein TW, Matsumoto CS. Intestinal replacement therapy: timing and indications for referral of patients to an intestinal rehabilitation and transplant program. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S147-S151.

Grant D, Abu-Elmagd K, Reyes J, et al. 2003 report of the Intestine Transplant Registry: a new era has dawned. Ann Surg. 2005;241:607-613.

Green M, Reyes J, Webber S, et al. The role of antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy in the prevention of Epstein-Barr virus infection and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease following solid organ transplantation, Transplant. Infect Dis. 2001;3:97-103.

Kauffman SS, Atkinson JB, Bianchi A, et al. Indications for pediatric intestinal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2001;5:80-87.

Kelly DA. Intestinal failure associated liver disease—what do we know today? Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2 Suppl):S70-S77.

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Data (website), http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/. Accessed May 7, 2010

Puntis J, Jenkins HR. Intestinal failure. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:919-920.

Reyes J, Mazariegos GV, Abu-Elmagd K, et al. Intestinal transplantation under tacrolimus monotherapy after perioperative lymphoid depletion with rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (thymoglobulin). Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1430-1436.

Reyes J, Mazariegos GV, Bond GM, et al. Pediatric intestinal transplantation: historical notes, principles and controversies. Pediatr Transplant. 2002;6:193-207.

Rogers J, Bueno J, Shapiro R, et al. Results of simultaneous and sequential pediatric liver and kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;72:1666-1670.

Salvia G, Guarino A, Terrin G, et al. Neonatal onset intestinal failure: an Italian multicenter study. J Pediatr. 2008;153:674-676.

Sherman PM, Mitchell DJ, Cutz E. Neonatal enteropathies: defining the causes of protracted diarrhea of infancy. J Pediatr Gastroeinerol Nutr. 2004;38:16-26.

Starzl TE, Demtris AJ, Trucco M, et al. Cell migration and chimerism after whole-organ transplantation: the basis of graft acceptance. Hepatology. 1993;17:1127-1156.

Testa G, Holterman M, John E, et al. Combined living donor liver/small bowel transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;27:1401-1404.