Chapter 322 Intestinal Atresia, Stenosis, and Malrotation

Initial treatment of infants and children with bowel obstruction must be directed at fluid resuscitation and stabilizing the patient. Nasogastric decompression usually relieves pain and vomiting. After appropriate cultures, broad-spectrum antibiotics are usually started in ill-appearing neonates with bowel obstruction and those with suspected strangulating infarction. Patients with strangulation must have immediate surgical relief before the bowel infarcts, resulting in gangrene and intestinal perforation. Extensive intestinal necrosis results in short bowel syndrome (Chapter 330.7). Nonoperative conservative management is usually limited to children with suspected adhesions or inflammatory strictures that might resolve with nasogastric decompression or anti-inflammatory medications. If clinical signs of improvement are not evident within 12-24 hr, then operative intervention is usually indicated.

322.1 Duodenal Obstruction

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

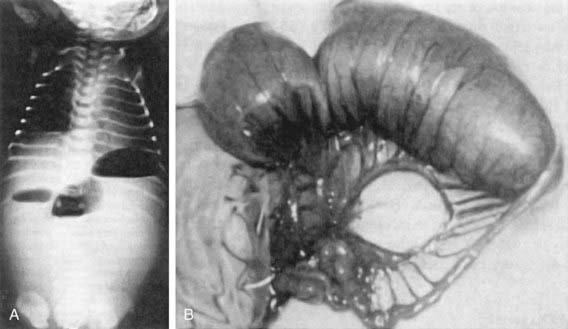

The diagnosis is suggested by the presence of a “double-bubble” sign on a plain abdominal radiograph (Fig. 322-1). The appearance is caused by a distended and gas-filled stomach and proximal duodenum, which are invariably connected. Contrast studies are occasionally needed to exclude malrotation and volvulus because intestinal infarction can occur within 6-12 hr if the volvulus is not relieved. Contrast studies are generally not necessary and may be associated with aspiration. Prenatal diagnosis of duodenal atresia is readily made by fetal ultrasonography, which reveals a sonographic double-bubble. Prenatal identification of duodenal atresia is associated with decreased morbidity and fewer hospitalization days.

Basu R, Burge DM. The effect of antenatal diagnosis on the management of small bowel atresia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:177-179.

Bittencourt DG, Barini R, Marba S, et al. Congenital duodenal obstruction: does prenatal diagnosis improve the outcome? Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:582-585.

Dalla Vecchia LK, Grosfeld JL, West KW, et al. Intestinal atresia and stenosis: a 25 year experience with 277 cases. Arch Surg. 1998;133:490-497.

De la Hunt MN. The acute abdomen in the newborn. Sem Fetal Neonat Med. 2006;11:191-197.

Escobar MA, Ladd AP, Grosfeld JL, et al. Duodenal atresia and stenosis: Long-term follow-up over 30 years. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:867-871.

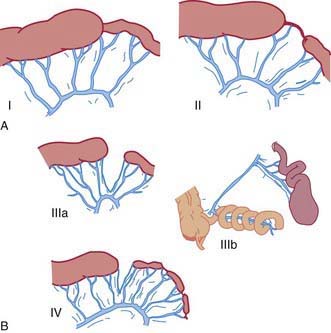

322.2 Jejunal and Ileal Atresia and Obstruction

Five types of jejunal and ileal atresias are encountered (Fig. 322-2). In type I, a mucosal web occludes the lumen but continuity is maintained between the proximal and distal bowel. Type II involves a small-diameter solid cord that connects the proximal and distal bowel. Type III is divided into two subtypes. Type IIIa occurs when both ends of the bowel end in blind loops, accompanied by a small mesenteric defect. Type IIIb is similar, but it is associated with an extensive mesenteric defect and a loss of the normal blood supply to the distal bowel. The distal ileum coils around the ileocolic artery, from which it derives its entire blood supply, producing an “apple-peel” appearance. This anomaly is associated with prematurity, an unusually short distal ileum, and significant foreshortening of the bowel. Type IV involves multiple atresias. Types II and IIIa are the most common, each accounting for 30-35% of cases. Type I occurs in approximately 20% of patients. Types IIIb and IV account for the remaining 10-20% of cases, with IIIb being the least common configuration.

Clinical Manifestation and Diagnosis

In patients with obstruction due to jejunoileal atresia or long-segment Hisrchprung disease, plain radiographs typically demonstrate multiple air-fluid levels proximal to the obstruction in the upright or lateral decubitus positions (Fig. 322-3). These levels may be absent in patients with meconium ileus because the viscosity of the secretions in the proximal bowel prevents layering. Instead, a typical hazy or ground-glass appearance may be appreciated in the right lower quadrant. This haziness is caused by small bubbles of gas that become trapped in inspissated meconium in the terminal ileal region. If there is meconium peritonitis, patchy calcification may also be noted, particularly in the flanks. Plain films can reveal evidence of pneumoperitoneum due to intestinal perforation. Air may be seen in the subphrenic regions on the upright view and over the liver in the left lateral decubitus position.

Kumaran N, Shankar KR, Lloyd DA, et al. Trends in the management and outcome of jejuno-ileal atresia. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002;12:163-167.

Werler MM, Sheehan JE, Mitchell AA. Association of vasoconstrictive exposures with risks of gastroschisis and small intestinal atresia. Epidemiology. 2003;14:349-354.

322.3 Malrotation

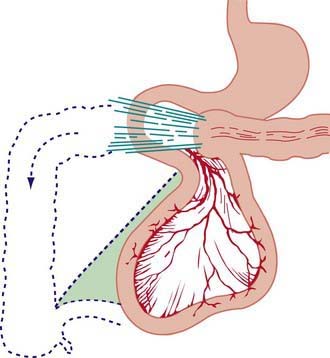

Nonrotation occurs when the bowel fails to rotate after it returns to the abdominal cavity. The 1st and 2nd portions of the duodenum are in their normal position, but the remainder of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum occupy the right side of the abdomen and the colon is located on the left. The most common type of malrotation involves failure of the cecum to move into the right lower quadrant (Fig. 322-4). The usual location of the cecum is in the subhepatic area. Failure of the cecum to rotate properly is associated with failure to form the normal broad-based adherence to the posterior abdominal wall. The mesentery, including the superior mesenteric artery, is tethered by a narrow stalk, which can twist around itself and produce a midgut volvulus. Bands of tissue (Ladd bands) can extend from the cecum to the right upper quadrant, crossing and possibly obstructing the duodenum.

Malrotation and nonrotation are often associated with other anomalies of the abdominal wall such as diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, and omphalocele. Malrotation is also associated with the heterotaxy syndrome, which is a complex of congenital anomalies including congenital heart malformations, malrotation, and either asplenia or polysplenia (Chapter 425.11).

Clinical Manifestation

Surgical intervention is recommended for any patient with a significant rotational abnormality, regardless of age. If a volvulus is present, surgery is done immediately as an acute emergency, the volvulus is reduced, and the duodenum and upper jejunum are freed of any bands and remain in the right abdominal cavity. The colon is freed of adhesions and placed in the right abdomen with the cecum in the left lower quadrant, usually accompanied by incidental appendectomy. This may be done laparoscopically if gut ischemia is not present, but it is generally done as an open procedure. The purpose of surgical intervention is to minimize the risk of subsequent volvulus rather than to return the bowel to a normal anatomic configuration. Proper surgical management of patients with heterotaxy remains in debate because these patients have a high incidence of malrotation but a low incidence of actual volvulus. It is unclear whether these patients should undergo elective Ladd procedure or whether watchful waiting is appropriate. Extensive intestinal ischemia from volvulus can result in short bowel syndrome (Chapter 330.7). Persistent symptoms after repair of malrotation should suggest a pseudo-obstruction–like motility disorder.

Applegate KE. Evidence based diagnosis of malrotation and volvulus. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(Suppl 2):S161-S163.

Basu R, Burge DM. The effect of antenatal diagnosis on the management of small bowel atresia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:177-179.

Escobar MA, Ladd AP, Grosfeld JL, et al. Duodenal atresia and stenosis: long-term follow-up over 30 years. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:867-871.

Forrester MB, Merz RD. Population-based study of small intestinal atresia and stenosis, Hawaii, 1986–2000. Public Health. 2004;118:434-438.

Karnak I, Ciftci AO, Senocak ME, et al. Colonic atresia: surgical management and outcome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001;17:631-635.

Khen N, Jaubert F, Sauvat F, et al. Fetal intestinal obstruction induces alteration of enteric nervous system development in human intestinal atresia. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:975-980.

Kumaran N, Shankar KR, Lloyd DA, et al. Trends in the management and outcome of jejuno-ileal atresia. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002;12:163-167.

Lampl B, Levin TL, Berdon WE, et al. Malrotation and midgut volvulus: a historical review and current controversies in diagnosis and management. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(4):359-366.

Mehall JR, Chandler JC, Mehall RL, et al. Management of typical and atypical intestinal malrotation. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1169-1172.

Millar AJ, Rode H, Cywes S. Malrotation and volvulus in infancy and childhood. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2003;12:229-236.

Pickhardt PJ, Bhalla S. Intestinal malrotation in adolescents and adults: spectrum of clinical and imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1429-1435.

Werler MM, Sheehan JE, Mitchell AA. Association of vasoconstrictive exposures with risks of gastroschisis and small intestinal atresia. Epidemiology. 2003;14:349-354.