Chapter 33 Interspinous Spacers

More than 2 million physician-related visits yearly can be attributed to symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis. Accordingly, spinal stenosis is perhaps the most common reason for low back surgery in patients older than 50 years [1–3]. As life expectancy increases and our population continues to age, the prevalence of symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis is expected to climb [4].

Surgical indications for treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis have not been clearly defined in the literature [5]. A decompressive laminectomy with or without fusion has been the surgical treatment of choice by most surgeons for those patients in whom conservative management of lumbar spinal stenosis has failed and who present with a poor quality of life secondary to pain and or limitations in walking tolerance. Johnsson and associates [6] compared patients with lumbar spinal stenosis who were treated surgically and nonsurgically. The group who underwent surgery reported 60% improvement, versus 30% in the nonsurgical group. A similar study by Atlas and colleagues [7] reported success rates of 55% and 28% for surgical and nonsurgical treatments, respectively, at 1 year [7]. In rare cases, such as acute cauda equina syndrome or progressive neurologic weakness, surgical indications are more clear-cut.

Complications associated with decompressive lumbar surgery beyond worsening pain and disability have included postoperative hematoma formation, neurologic deficits, wound healing problems, and even death [8–14]. A review of the pertinent literature has identified several medical comorbidities and risk factors that may increase risks of decompressive surgery. These include diabetes, obesity, cardiac disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid disease, depression, smoking, and long duration of symptoms [15–19]. Furthermore, results of decompressive surgery vary from study to study, in that 30% to 70% of patients report significant improvement in overall symptoms [20]. Some deterioration of surgical results has also been shown to occur over time [21].

At the time of this publication, a handful of interspinous spacers are available for implantation. The X-STOP Interspinous Process Decompression System (Kyphon, Sunnyvale, CA) is a device approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for implantation at one or two levels in patients with neurogenic claudication due to lumbar spinal stenosis. Prospective data from investigational device exemption (IDE) studies have shown the X-STOP device to be superior to conservative nonsurgical care for selected patients [22]. Studies have also shown that the implant may reduce pressure on the facet joints and improve overall canal dimensions [23,24].

The Wallis Normalization System (Abbott Spine, Austin, TX) and the Device for Intervertebral Assisted Motion (DIAM) (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN) are currently under clinical investigation as nonfusion devices to treat spinal stenosis and other degenerative spinal conditions. Although different in overall design, both devices are implanted between the spinous processes and have shown favorable results in their “infancy” [25–27].

The Coflex Interspinous Spacer (Paradigm Spine, New York, NY) is another interspinous spacer with origins in France in the mid 1990s. The device has been used in Europe and is currently undergoing clinical trials in the United States. This is a U-shaped implant that is placed between the spinous processes and is designed to improve the cross-sectional diameter of the spinal canal [28].

The SUPERION Interspinous Spacer (VertiFlex, Inc., San Clemente, CA) was developed as another minimally invasive device to treat neurogenic claudication. This implant is composed of titanium alloy and is delivered by way of a small portal through the supraspinous ligament. Biomechanical studies have shown improvements in foraminal height, width, and area following implantation of this device [29].

A host of other interspinous spacers are currently in development.

Presurgical treatments

Conservative nonsurgical treatment for symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis consists of activity modification, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and, in some cases, corticosteroid injections. Referral to a pain management specialist may be warranted. Patients with symptoms that are mild in nature may be experience adequate relief with nonsurgical measures. Those with moderate symptoms may not experience improvement, as several studies have shown [6,7]; surgical intervention may be warranted for this group of patients.

Preoperative preparations

Diagnostic Testing

The use of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) testing to evaluate bone density has been advocated by many surgeons, especially in postmenopausal women who are contemplating surgical intervention with instrumentation [30].

Procedures and technique

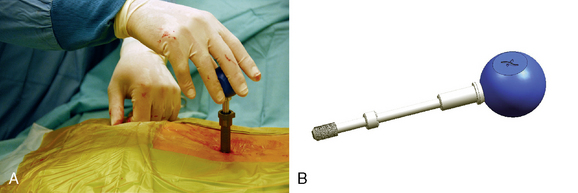

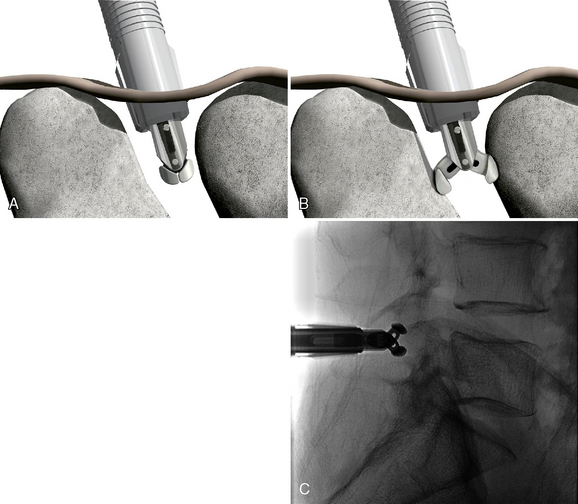

The SUPERION Interspinous Spacer will be used for the purposes of describing the implantation technique for lumbar spinal stenosis (Fig. 33-1):

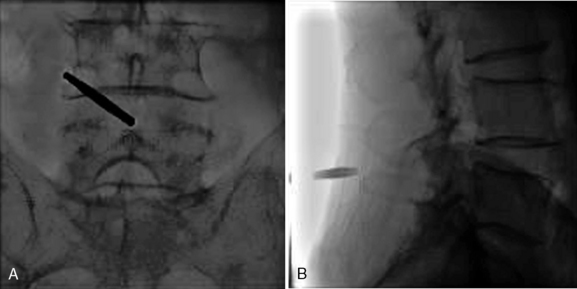

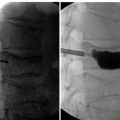

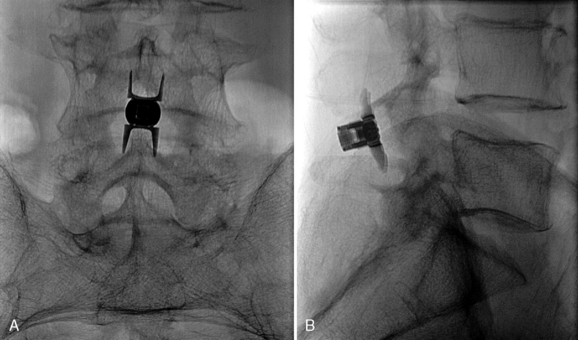

Figure 33–11 Final anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) fluoroscopic radiographs confirming placement of the implant.

CASE STUDY 33.1 Spinal Stenosis at the L5-S1 Level Treated by Superion Interspinous Spacer

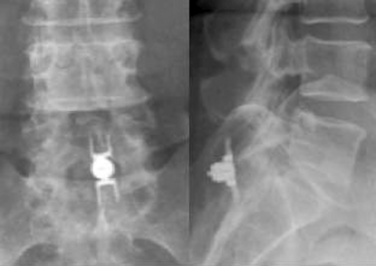

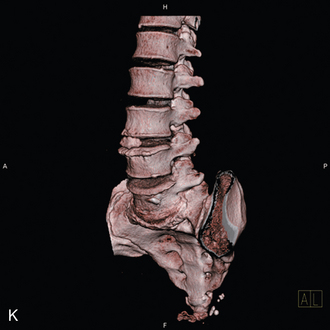

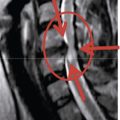

A 59-year-old woman presented with an 8-month history of low back and severe left leg pain with moderate weakness that had not been relieved with more than 6 months of nonsurgical management. Baseline radiographs (Fig. 33-12) and magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a diagnosis of spinal stenosis at the L5-S1 level.

The patient was placed in the prone position on an operating table capable of C-arm fluoroscopy. With the patient under general anesthesia, a 2-cm midline incision was made at the L5-S1 level. The L5-S1 interspinous space was sequentially dilated to accommodate the SUPERION cannula, and the interspinous space was prepared with use of an interspinous reamer. The interspinous space was measured and a 13-mm SUPERION device was implanted between the L5-S1 spinous processes (Fig. 33-13), with a total surgical time of 20 minutes and an estimated blood loss of less than 50 mL.

1 Long D.M., BenDebba M., Torgerson W.S., et al. Persistent back pain and sciatica in the United States: patient characteristics. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:40-58.

2 Fanuele J.C., Birkmeyer N.J., Abdu W.A., et al. The impact of spinal problems on the health status of patients: have we underestimated the effect? Spine. 2000;25:1509-1514.

3 Hart L.G., Deyo R.A., Cherkin D.C. Physician office visits for low back pain: frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a U.S. national survey. Spine. 1995;20:1-9.

4 Arbit E., Pannullo S. Lumbar stenosis: a clinical review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;384:137-143.

5 Birkmeyer N.J., Weinstein J.N. Medical versus surgical treatment for low back pain: evidence and clinical practice. Eff Clin Pract. 1999;2:218-227.

6 Johnsson K.E., Udén A., Rosén I. The effect of decompression on the natural course of spinal stenosis: a comparison of surgically treated and untreated patients. Spine. 1991;16:615-619.

7 Atlas S.J., Keller R.B., Robson D., et al. Surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis: four-year outcomes from the Maine lumbar spine study. Spine. 2000;25:556-562.

8 Ain M.C., Chang T.L., Schkrohowsky J.G., et al. Rates of perioperative complications associated with laminectomies in patients with achondroplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:295-298.

9 Yuan P.S., Booth R.E.Jr, Albert T.J. Nonsurgical and surgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:303-312.

10 Jönsson B., Strömqvist B. Lumbar spine surgery in the elderly: complications and surgical results. Spine. 1994;19:1431-1435.

11 Matsui H., Tsuji H., Kanamori M., et al. Laminectomy-induced arachnoradiculitis: a postoperative serial MRI study. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:660-666.

12 Shektman A., Granick M.S., Solomon M.P., et al. Management of infected laminectomy wounds. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:307-309.

13 Jansson K.A., Blomqvist P., Granath F., Németh G. Spinal stenosis surgery in Sweden 1987–1999. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:535-541.

14 Smith D.W., Lawrence B.D. Vascular complications of lumbar decompression laminectomy and foraminotomy: a unique case and review of the literature. Spine. 1991;16:387-390.

15 Arubzon Z., Adunsky A., Fidelman Z., Gepstein R. Outcomes of decompression surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in elderly diabetic patients. Eur Spine J. 2004;13:32-37.

16 Lehto M., Honkanen P. Factors influencing the outcome of operative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;137:25-28.

17 Patel N., Bagan B., Vadera S., et al. Obesity and spine surgery: relation to perioperative complications. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:291-297.

18 Sinikallio S., Aalto T., Airaksinen O., et al. Depression is associated with poorer outcome of lumbar spinal stenosis surgery. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:905-912.

19 Katz J.N., Lipson S.J., Larson M.G., et al. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:809-816.

20 Turner J.A., Ersek M., Herron L., Deyo R. Surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: attempted meta-analysis of the literature. Spine. 1992;17:1-8.

21 Jönsson B., Annertz M., Sjöberg C., Strömqvist B. A prospective and consecutive study of surgically treated lumbar spinal stenosis: Part II: Five-year follow-up by an independent observer. Spine. 1997;22:2938-2944.

22 Zucherman J.F., Hsu K.Y., Hartjen C.A., et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized trial evaluating the X STOP interspinous process decompression system for the treatment of neurogenic intermittent claudication: two-year follow-up results. Spine. 2005;30:1351-1358.

23 Wiseman C.M., Lindsey D.P., Fredrick A.D., Yerby S.A. The effect of an interspinous process implant on facet loading during extension. Spine. 2005;30:903-907.

24 Richards J.C., Majumdar S., Lindsey D.P., et al. The treatment mechanism of an interspinous process implant for lumbar neurogenic intermittent claudication. Spine. 2005;30:744-749.

25 Sénégas J. Mechanical supplementation by non-rigid fixation in degenerative intervertebral lumbar segments: the Wallis system. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(Suppl. 2):S164-S169.

26 Boeree N.. Dynamic stabilization of the lumbar motion segment with the Wallis system. 2005 Presented at the 5th Annual SAS [Spinal Arthroplasty Society] Global Symposium on Motion Preservation Technology, New York; May 3–6

27 Guizzardi G., Petrini P., Fabrizi A.P., et al. The use of DIAM (interspinous stress-breaker device) in the DDD: italian multicenter clinical experience. 2005 Presented at the 5th Annual SAS [Spinal Arthroplasty Society] Global Symposium on Motion Preservation Technology, New York; May 3–6

28 Eif M., Schenke H.. The Interspinous U: indications, experience, and results. 2005 Presented at the 5th Annual SAS [Spinal Arthroplasty Society] Global Symposium on Motion Preservation Technology, New York; May 3–6

29 SUPERION data on file. San Clemente, CA: VertiFlex, Inc, 2007.

30 Okuyama K., Abe E., Suzuki T., et al. Influence of bone mineral density on pedicle screw fixation: a study of pedicle screw fixation augmenting posterior lumbar interbody fusion in elderly patients. Spine J. 2001;1:402-407.