4 Interscalene Block

Traditional Block Technique

Placement

Anatomy

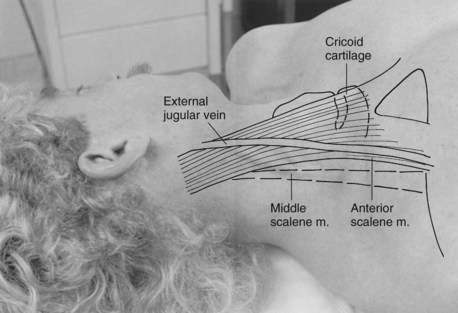

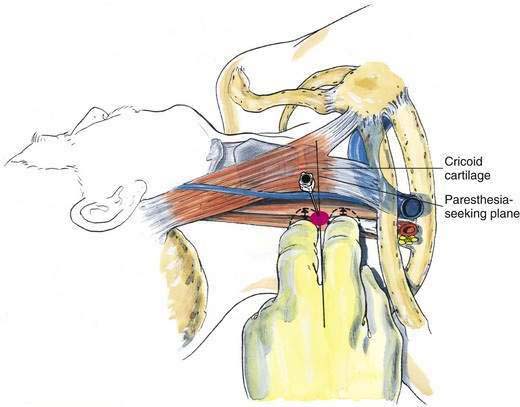

Surface anatomy of importance to anesthesiologists includes the larynx, sternocleidomastoid muscle, and external jugular vein. Interscalene block is most often performed at the level of the C6 vertebral body, which is at the level of the cricoid cartilage. Thus, by projecting a line laterally from the cricoid cartilage, one can identify the level at which one should roll the fingers off the sternocleidomastoid muscle onto the belly of the anterior scalene and then into the interscalene groove. When firm pressure is applied, in most individuals it is possible to feel the transverse process of C6, and in some people it is possible to elicit a paresthesia by deep palpation. The external jugular vein often overlies the interscalene groove at the level of C6, although this should not be relied on (Fig. 4-1).

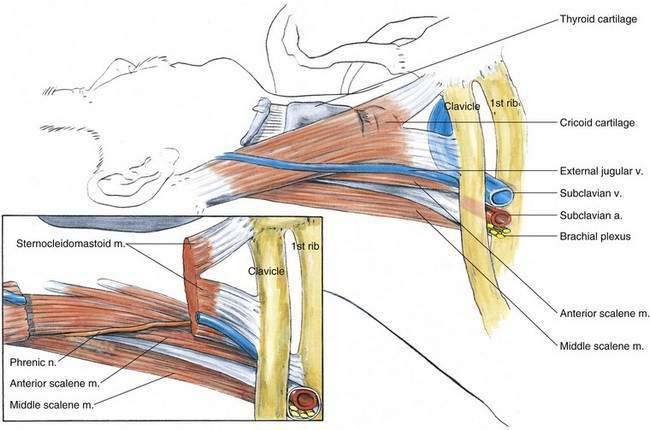

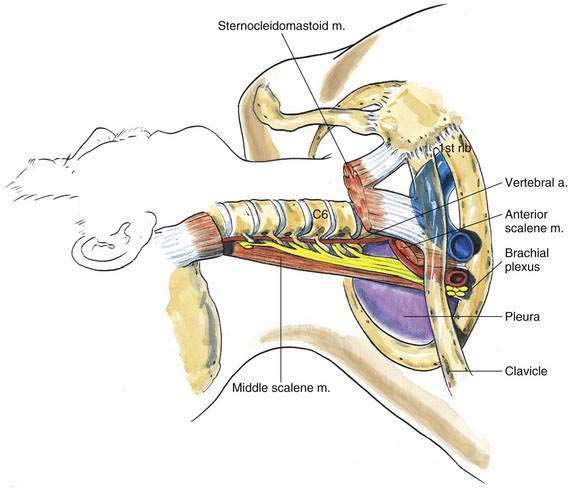

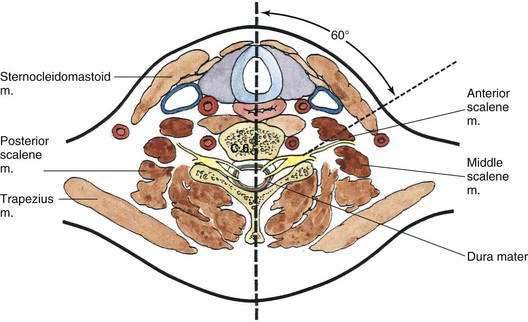

It is important to visualize what lies under the palpating fingers; again, the key to carrying out successful interscalene block is the identification of the interscalene groove. Figure 4-2 allows us to look beneath surface anatomy and develop a sense of how closely the lateral border of the anterior scalene muscle deviates from the border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. This feature should be constantly kept in mind. The anterior scalene muscle and the interscalene groove are oriented at an oblique angle to the long axis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Figure 4-3 removes the anterior scalene and highlights the fact that at the level of C6, the vertebral artery begins its route to the base of the brain by traveling through the root of the transverse process in each of the more cephalad cervical vertebrae.

Position

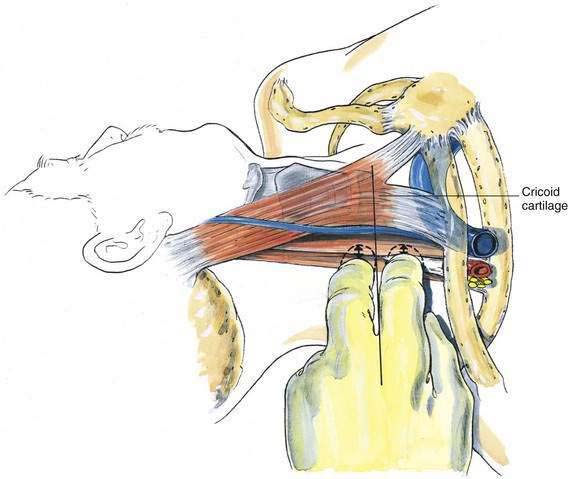

The patient lies supine with the neck in the neutral position and the head turned slightly opposite the site to be blocked. The anesthesiologist then asks the patient to lift the head off the table to tense the sternocleidomastoid muscle and allow identification of its lateral border. The fingers then roll onto the belly of the anterior scalene and subsequently into the interscalene groove. This maneuver should be carried out in the horizontal plane through the cricoid cartilage—thus, at the level of C6. To roll the fingers effectively (Fig. 4-4), the operator should stand at the patient’s side.

Needle Puncture

When the interscalene groove has been identified and the operator’s fingers are firmly pressing in it, the needle is inserted, as shown in Figure 4-5, in a slightly caudal and slightly posterior direction. As a further directional help, if the needle for this block is imagined to be long and inserted deeply enough, it would exit the neck posteriorly in approximately the midline at the level of the C7 or T1 spinous process. If a paresthesia or motor response is not elicited on insertion, the needle is “walked,” while maintaining the same needle angulation as shown in Figure 4-4, in a plane joining the cricoid cartilage to the C6 transverse process. Because the brachial plexus traverses the neck at virtually a right angle to this plane, a paresthesia or motor response is almost guaranteed if small enough steps of needle reinsertion are carried out. When undertaking the block for shoulder surgery, this is probably the one brachial plexus block in which a large volume of local anesthetic coupled with a single needle position allows effective anesthesia. For shoulder surgery, 25 to 35 mL of lidocaine, mepivacaine, bupivacaine, or ropivacaine can be used. If the interscalene block is being carried out for forearm or hand surgery, a second, more caudal needle position is desirable, in which 10 to 15 mL of additional local anesthetic is injected to allow spread along more caudal roots.

Pearls

If there is difficulty in identifying the anterior scalene muscle, one maneuver is to have the patient maximally inhale while the anesthesiologist palpates the neck. During this maneuver the scalene muscles should contract before the sternocleidomastoid muscle contracts, and this may allow clarification of the anterior scalene muscle in the difficult-to-palpate neck. Further, if the operator is finding it difficult to elicit a paresthesia or produce a motor response during nerve stimulation with this block, it is almost always because the needle entry site has been placed too far posteriorly. For example, Figure 4-6 shows that if the right side of the neck is divided into a 180-degree arc, the needle entry site should be approximately at 60 degrees from the sagittal plane to optimize production of the block.

Ultrasonography-Guided Technique

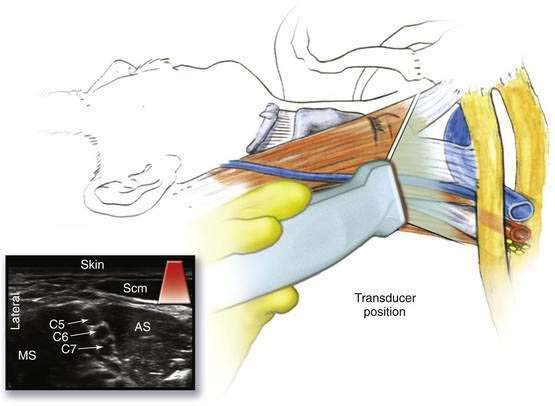

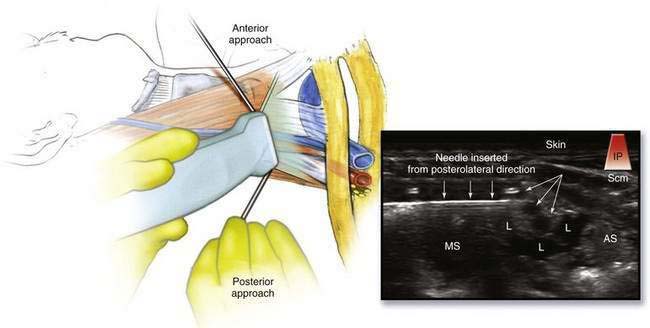

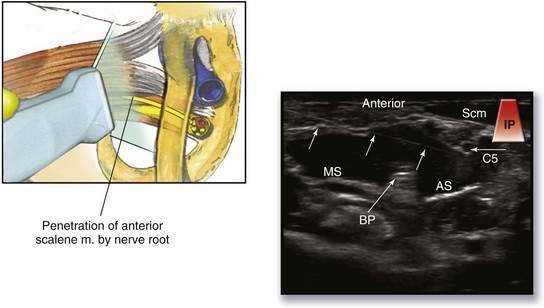

The goals of an ultrasonography-guided interscalene nerve block include defining normal anatomy, visualizing the brachial plexus, observing the advancing needle, and confirming correct intrasheath spread of local anesthetic. With the patient in the same position as for the surface landmark technique, the ultrasound transducer is placed in the midneck at the level of the cricoid cartilage. The operator should be at the head of the patient’s bed, directing the transducer with his or her nondominant hand (Fig. 4-7). The first two structures identified are the carotid artery (a pulsatile, hypoechoic circle that resists compression) and internal jugular vein (a nonpulsatile and compressible hypoechoic circle). The probe is then moved in a lateroposterior direction approximately 1 to 2 cm. This should generate the sonogram depicted in Figure 4-7. The brachial plexus can be seen between the anterior and middle scalene muscles as distinct hypoechoic circles with hyperechoic rings. The scalene muscles appear as hypoechoic ovals or circles lying deep to the overlying hypoechoic and triangle-shaped sternocleidomastoid muscle. Using the in-plane approach, the needle is inserted through either the middle scalene muscle (posterior approach) or the anterior scalene muscle (anterior approach); refer to Figure 4-8 for orientation. The needle is advanced until it enters into the brachial plexus sheath between the C5 and C6 ventral nerve roots. A distinct “popping” sensation is both felt and visualized ![]() (see Video 2: Interscalene Nerve Block: In-Plane Technique on the Expert Consult Website). After a test injection, the solution should be seen filling the brachial plexus sheath (see Fig. 4-8). If intramuscular spread is noted, the needle should be repositioned.

(see Video 2: Interscalene Nerve Block: In-Plane Technique on the Expert Consult Website). After a test injection, the solution should be seen filling the brachial plexus sheath (see Fig. 4-8). If intramuscular spread is noted, the needle should be repositioned.

Pearls

The operator should be on the lookout for common anatomic variants that can compromise the quality of the nerve block. Cadaver studies suggest that the “typical” situation of the brachial plexus lying between the anterior and middle scalene muscles exists in only 60% of situations. The most common variation (34%) is direct penetration of the anterior scalene muscle by the C5 or C6 ventral nerve roots (Fig. 4-9). Such anatomic variations explain failure of surface landmark–based approaches to the interscalene block in which the scalene muscle may serve as a barrier to the distribution of local anesthesia. In these special situations, several injections may be necessary given the anatomic separation of the nerve roots (see Fig. 4-9).