14 Intermittent Positive-Pressure Breathing

Note 1: This book is written to cover every item listed as testable on the Entry Level Examination (ELE), Written Registry Examination (WRE), and Clinical Simulation Examination (CSE)

The listed code for each item is taken from the National Board for Respiratory Care’s (NBRC) Summary Content Outline for CRT (Certified Respiratory Therapist) and Written RRT (Registered Respiratory Therapist) Examinations (http://evolve.elsevier.com/Sills/resptherapist/). For example, if an item is testable on both the ELE and the WRE, it will simply be shown as: (Code: …). If an item is only testable on the ELE, it will be shown as: (ELE code: …). If an item is only testable on the WRE, it will be shown as: (WRE code: …).

MODULE A

1. Description

Shapiro and associates (1991) list the following as the physiologic effects of IPPB:

a. Increased mean airway pressure

By definition of IPPB, the patient is receiving a positive airway pressure instead of generating a negative intrathoracic pressure to create the VT. Most authors recommend that patients with heart disease be monitored closely for the effects of increased mean airway pressure. Decreasing the normal return of venous blood to the heart, thereby decreasing the cardiac output, is possible. Shapiro and associates (1991) recommend an expiratory time that is long enough to allow for normal venous return before the next positive-pressure breath is given. The patient’s heart rate and blood pressure can be monitored to ensure that they stay in the normal range.

d. Alteration of the inspiratory/expiratory ratio

Patients with high airway resistance or low lung compliance often change their breathing patterns to reduce the WOB (see Chapter 1). These new breathing patterns may lead to worsening of the patient’s condition. Alteration of normal ventilation and perfusion ratios in the lungs may worsen hypoxemia. Properly administered and coached IPPB can be used to adjust the inspiratory/expiratory (I:E) ratio to the benefit of the patient. The patient can be taught how to breathe in a more physiologically normal pattern.

2. Indications

The following indications and guidelines are listed in the American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC) Clinical Practice Guidelines (1991, 2003) on IPPB:

a. To treat atelectasis when other deep breathing methods are ineffective

Patients who are uncooperative, unconscious, or physically incapable of being coached in deep-breathing and coughing techniques or in performing incentive spirometry (IS) may be helped by IPPB. An inspiratory pause at the end of the IPPB breath helps to better distribute the gas to open areas of atelectasis. As has been discussed in Chapter 7, a patient would benefit from IPPB rather than IS if any of the following apply:

c. To enhance the patient’s cough effort and sputum clearance

The following additional indications were listed in the Guidelines for the Use of Intermittent Positive Pressure Breathing (IPPB) published by the Respiratory Care Committee of the American Thoracic Society (1980).

d. To treat impending ventilatory failure as seen by an increased arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2)

It may be possible to delay or avoid intubation and mechanical ventilation in the deteriorating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patient. The patient is able to relax and reduce the work of breathing (WOB) during a passive IPPB treatment. It may be necessary to give IPPB for 5 to 10 minutes as often as every 30 minutes to 1 hour. The treatment should also be given with the intention of helping the patient’s cough and sputum clearance. (An alternative to frequent IPPB treatments is noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation. This is discussed in Chapter 15.)

e. To help manage the patient with acute pulmonary edema

IPPB can help in the management of this patient by temporarily increasing mean airway pressure. This reduces the venous return to the heart, which may reduce pulmonary edema. The IPPB procedure does not correct the underlying cardiac problem, which must be treated by other means.

4. Hazards and precautions

The AARC guidelines list the following hazards and precautions for IPPB therapy:

5. Initiation of therapy

a. Steps in the basic procedure

c. Giving an active treatment

Welch and colleagues (1980) have found that the patient’s posttreatment IC is greatest when the practitioner (1) uses as high a peak pressure as the patient can tolerate and (2) coaches the patient to inhale as deeply as possible with the IPPB machine. They and others believe that this is the best way to treat or prevent atelectasis. Monitor the patient for signs of barotrauma/volutrauma.

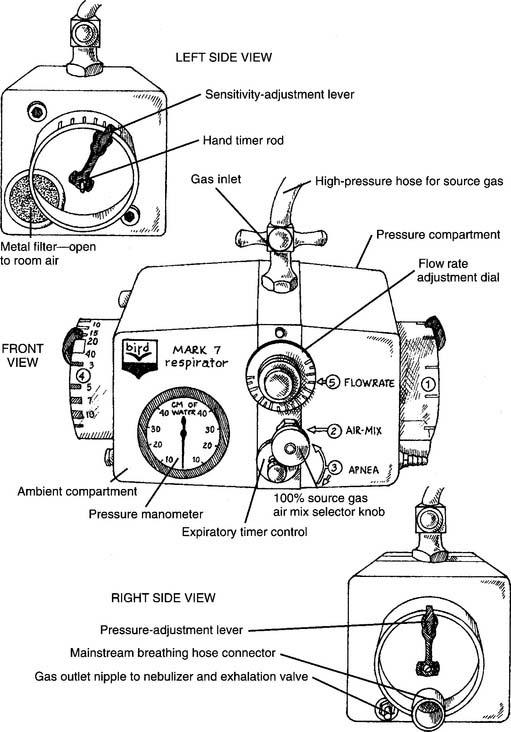

6. Initial settings on the Bird Mark 7

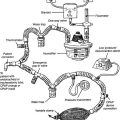

The older version of the Mark 7 is used as the model respirator of the Bird series. The current Mark 8 has similar features. Other Bird units have slightly different controls and features. Refer to Figure 14-1 for the following:

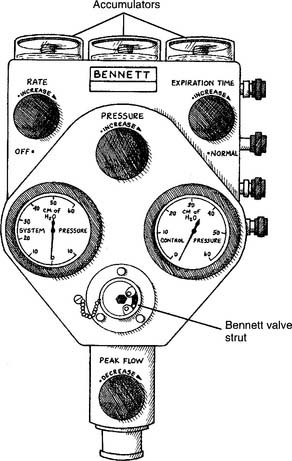

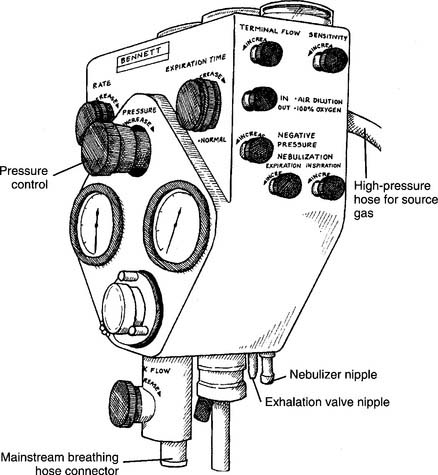

7. Initial settings on the Bennett PR-2

The PR-2 is used as the model respirator of the Bennett series. (Although the PR-2 is no longer being manufactured, many are still in clinical use.) Other Bennett units have slightly different controls and features. Refer to Figures 14-2 and 14-3 for the following:

MODULE B

1. Change the patient-machine interface

a. Mouthpiece

A conscious, cooperative patient can take a treatment with a mouthpiece. He or she must be instructed to place the mouthpiece between the teeth (or gums) and seal the lips around it so that there is no leak. Instruct the patient to sip gently on it to turn on the IPPB machine. As long as the lips are sealed and there are no other leaks, the positive-pressure breath will stop when the preset pressure is reached. Nose clips are often helpful to prevent a leak through the nose as the patient is learning how to take the treatment. The nose clips can be removed after the patient has learned how to seal the nasopharynx with the soft palate.

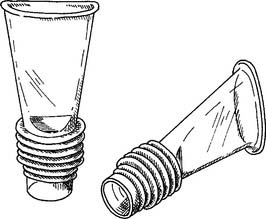

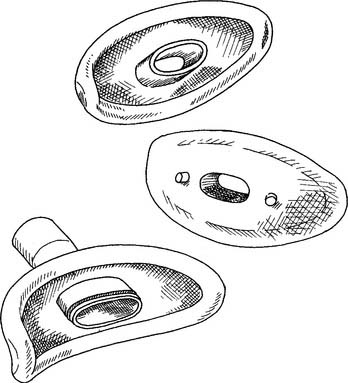

A variety of mouthpieces are available. All share two common features: a raised edge so that the teeth do not slip off; and a 22-mm outer diameter (OD) connector end to insert into the IPPB circuit (Figure 14-4).

b. Mouth seal (Bennett seal)

An unconscious, uncooperative, or aged patient who cannot seal his or her lips can be aided by placing a soft rubber seal around the mouthpiece. The practitioner gently holds the seal around the patient’s lips to seal the airway so that the patient can trigger the breath and cycle the machine off (Figure 14-5). Nose clips are also commonly needed.

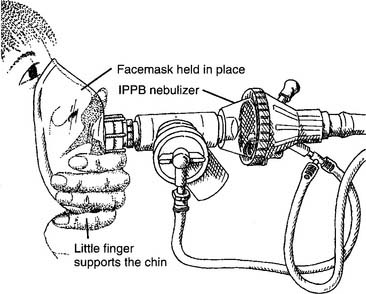

c. Face mask

The mask should be clear and properly sized to fit comfortably over the patient’s nose and mouth. The practitioner should be able to get a seal with a minimum amount of hand pressure (Figure 14-6). The equipment connection opening in the mask has a 22-mm inner diameter (ID) so that it connects directly to the IPPB circuit. A 22-mm-OD male adapter and short length of aerosol tubing can be added for flexibility and patient comfort. The clear mask is important so that the practitioner can see whether the patient has vomited or has a large amount of secretions or saliva in his or her mouth. The mask should never be strapped to the patient’s face so that the practitioner can attend to another patient.

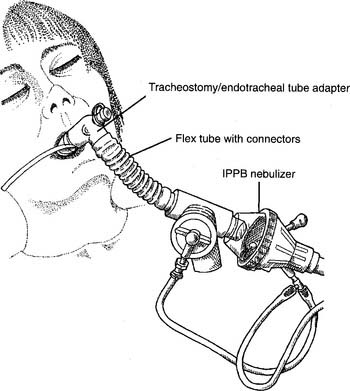

d. Tracheostomy/endotracheal tube (elbow) adapter

The elbow adapter is designed to connect the patient’s tracheostomy or endotracheal tube to the IPPB circuit (or other respiratory care equipment). The IPPB end has a 22-mm-ID connector. The tracheostomy/endotracheal tube end has a 15-mm-ID connector (Figure 14-7). If the tube’s cuff has been deflated, it must be reinflated to seal the airway. An unsealed cuff results in an air leak, and the gas flow will not turn off.

2. Improve patient synchrony (Code: IIIG3a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

a. Adjust the sensitivity

The sensitivity of the IPPB unit refers to how much effort or work the patient must perform to turn the unit on for a breath. Commonly, the sensitivity is set so that the patient has to generate a negative pressure of only about −1 cm H2O pressure to begin an inspiration. This can be seen by the needle deflecting into the negative range on the pressure manometer. Ask the patient whether the machine can be easily turned on to get a breath. The IPPB unit should not be set at a level so sensitive that it self-cycles.

b. Adjust the flow

3. Adjust the fractional concentration of inspired oxygen

For varying oxygen percentages on the Mark 7, note the following guidelines:

For varying oxygen percentages on the PR-II, note the following guidelines:

4. Adjust the volume, pressure, or both

Therefore the patient should receive an IPPB-assisted tidal volume of at least 1122 mL.

5. Reduce auto-PEEP (Code: IIIG3l) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is pressure added through a mechanical ventilator at the end of an exhalation to prevent the patient from exhaling fully. PEEP keeps the patient’s airway pressure greater than atmospheric (commonly given as the baseline pressure of zero). The clinical effect of PEEP is to increase a patient’s residual volume (RV) and functional residual capacity (FRC) to improve oxygenation. It is used when the patient has a clinical condition, such as atelectasis or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), that results in small lung volumes. Auto-PEEP is end-expiratory pressure in the lungs that cannot be seen on the IPPB unit’s (or ventilator’s) pressure manometer. Auto-PEEP is caused by air trapping because the patient does not have enough time to exhale completely. In other words, the patient starts another inspiration before the previous breath was completely exhaled. This problem is most commonly seen in patients with small airways disease such as asthma and COPD.

The following two procedures can be used to help identify the presence of auto-PEEP:

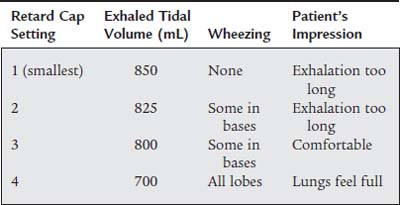

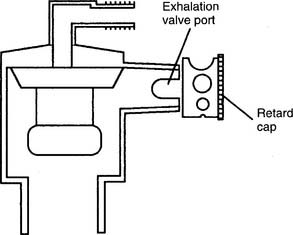

Bird makes a retard cap that fits over the exhalation valve port on their permanent circuit. The cap has a series of different size holes through which the exhaled gas can pass (Figure 14-8). By rotating the cap progressively from the largest to the smallest opening and evaluating the patient at each setting, the proper size opening and amount of retard can be determined. The largest hole results in the least expiratory retard, while the smallest hole results in the greatest retard.

Figure 14-8 Bird retard cap for providing adjustable expiratory resistance.

(From McPherson SP: Respiratory therapy equipment, ed 5, St Louis, 1995, Mosby.)

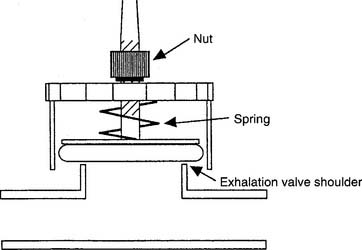

Bennett makes a retard exhalation valve that can be substituted for the regular exhalation valve on their permanent circuit (Figure 14-9). The valve consists of a spring attached to a nut and a diaphragm. As the nut is turned counterclockwise the spring pushes the diaphragm closer to the exhalation valve opening. This causes resistance to the exhalation of the tidal volume and a back-pressure is created against the airways. Start with the least amount of expiratory retard and evaluate the patient before increasing the amount of expiratory retard. Be aware that if too much pressure is placed against the exhalation valve opening, the patient will not be able to exhale back to atmospheric pressure. This would create PEEP and should not be done without an order from the physician.

MODULE C

1. Get the proper IPPB circuit for the patient’s treatment

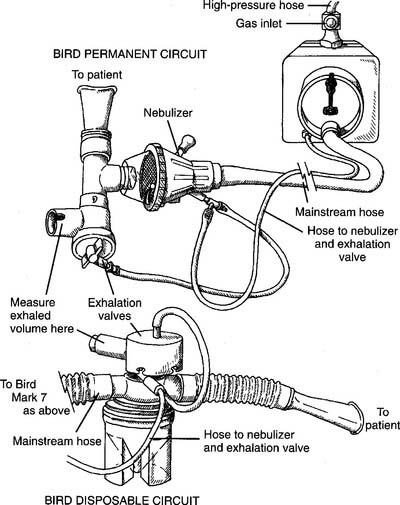

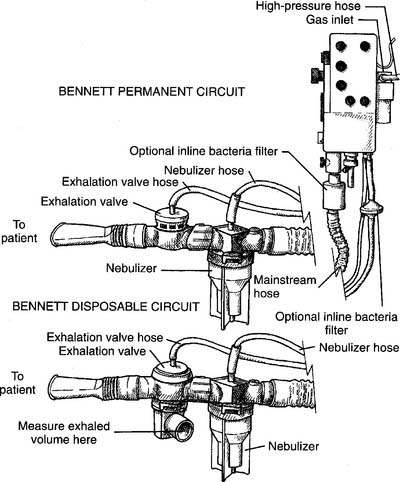

The two most widely used IPPB machines are the Bird Mark 7/8 (or a variation of it found in the series) and the Bennett PR-2. Both are pneumatically powered and found in most hospitals. Each unit requires a circuit that is designed specifically for it. See Figure 14-10 for a drawing of a permanent (reusable after cleaning) and disposable circuit for a Bird machine. See Figure 14-11 for a drawing of a permanent (reusable after cleaning) and disposable circuit for a Bennett machine.

2. Put the IPPB circuit together and make sure that it works properly

See Figure 14-10 for the Bird setup and Figure 14-11 for the Bennett setup.

a. General setup procedures

b. Bird setup

c. Bennett setup

3. Troubleshoot any problems with the equipment

Fixing a problem is only possible after the problem has been identified. The practitioner should be familiar with both permanent and disposable types of Bird and Bennett circuits. Leaks of any sort in the circuit prevent the unit from cycling off so that the patient can exhale. Tighten any friction-fit or screw-type connections to stop the leak. A leak at the source gas connection or high-pressure hose gas inlet connection results in a rather loud hissing sound. When connections are tightened properly, the hissing and leak will stop.

MODULE D

1. Analyze available information to determine the patient’s pathophysiologic state (Code: IIIH1) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Atelectasis is determined by characteristic chest radiograph findings and decreased or absent breath sounds over the affected area. Wheezing breath sounds is a finding indicating bronchospasm. Pulmonary edema has characteristic chest radiograph findings and cardiovascular indicators. Review the discussion on these conditions and their findings in Chapters 1 and 5. IPPB has been used in the management of patients with these conditions if other methods are not effective.

2. Determine the appropriateness of the prescribed respiratory care plan and recommend modifications when indicated

a. Determine the appropriateness of the prescribed therapy and goals for the patient’s pathophysiologic state (Code: IIIH3) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

b. Review the planned therapy to establish the therapeutic plan (Code: IIIH2a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

c. Recommend changes in the therapeutic plan when indicated (Code: IIIH4) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

d. Terminate the IPPB treatment if the patient has an adverse reaction to it (Code: IIIF1) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

3. Respiratory care protocols

c. Explain planned therapy and goals to the patient in understandable (nonmedical) terms to achieve the best results from the treatment (Code: IIIA6) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

e. Communicate the outcomes of therapy and change the therapy based on the protocol (Code: IIIA5) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Inform the patient’s nurse or physician and the supervising therapist if any serious question or problem occurs with the patient. Routine communication should occur as needed between these people and any other caregiver.

4. Record and evaluate the patient’s response to the treatment, including the following:

a. Record and interpret the following: heart rate and rhythm, respiratory rate, blood pressure, body temperature, and pain level (Code: IIIA1b4) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

b. Record and interpret the patient’s breath sounds (Code: IIIA1b3) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

AARC Clinical Practice Guideline. Incentive spirometry. Respir Care. 1991;30:1402.

AARC Clinical Practice Guideline. Intermittent positive pressure ventilation. Respir Care. 1993;38:1189.

AARC Clinical Practice Guideline. Intermittent positive pressure ventilation—2003 revision & update. Respir Care. 2003;48:540.

Branson RD, Hess DR, Chatburn RL, editors. Respiratory care equipment, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

Cairo JM. Lung expansion devices. In Cairo JM, Pilbeam SP, editors: Mosby’s respiratory care equipment, ed 9, St. Louis: Mosby, 2010.

Eubanks DH, Bone RC. Comprehensive respiratory care, ed 2. St Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Fink JB. Volume expansion therapy. In Burton GG, Hodgkin JE, Ward JJ, editors: Respiratory care, ed 4, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1997.

Fink JB. Bronchial hygiene and lung expansion. In: Fink JB, Hunt GE, editors. Clinical practice in respiratory care. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

Fink JB. Volume expansion therapy. In Burton GG, Hodgkin JE, Ward JJ, editors: Respiratory care, ed 4, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1997.

Fink JB. Hess DR: Secretion clearance techniques. In: Hess DR, MacIntyre NR, Mishoe SC, editors. Respiratory care principles & practices. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002.

Fluck RJJr. Intermittent positive-pressure breathing devices and transport ventilators. In Barnes TA, editor: Respiratory care practice, ed 2, St Louis: Mosby, 1994.

McPherson SP. Respiratory care equipment, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Miller WF. Intermittent positive pressure breathing (IPPB). In: Kacmarek RM, Stoller JK, editors. Current respiratory care. Philadelphia: BC Decker, 1988.

Respiratory Care Committee of the American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the use of intermittent positive pressure breathing (IPPB). Respir Care. 1980;25:365.

Shapiro BA, Kacmarek RM, Cne RD, et al. Clinical application of respiratory care, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby, 1991.

Weizalis CP. Intermittent positive-pressure breathing. In Barnes TA, editor: Respiratory care practice, ed 2, St. Louis: Mosby, 1994.

Welch MA, et al. Methods of intermittent positive pressure breathing. Chest. 1980;78:463.

White GC. Equipment theory for respiratory care, ed 4. Albany, NY: Delmar, 2005.

Wilkins RL. Lung expansion therapy. In Wilkins RL, Stoller CL, Kacmarek RM, editors: Egan’s fundamentals of respiratory care, ed 9, St. Louis: Mosby, 2009.

SELF-STUDY QUESTIONS FOR THE ENTRY LEVEL EXAM See page 597 for answers

SELF-STUDY QUESTIONS FOR THE WRITTEN REGISTRY EXAM See page 622 for answers

Based on this information, which retard cap setting would you recommend?