Intensive Care Unit Administration and Performance Improvement

THE PRESENT-DAY CRITICAL CARE LANDSCAPE

IDEALIZED DESIGN FOR CRITICAL CARE PRACTICE

STATE OF CRITICAL CARE REIMBURSEMENT

The delivery of critical care services continues to represent a disproportionate share of health care expenditures relative to the proportion of patients who use these services. The federal Medicare program has become the largest provider of health care insurance in the United States and in 2002 accounted for nearly 30% of annual payments to hospitals.1 An analysis of Medicare admissions in 2000 determined that cases involving a stay in an intensive care unit (ICU) cost nearly three times as much as those limited to the general care wards. Nevertheless, only 83% of the cost of the care of ICU patients was reimbursed, compared with 105% for patients cared for on the general care floors.2 Over the subsequent 5 years, critical care costs reportedly increased another 44%.3

Accordingly, the principal consideration for ICU administrators becomes a question of what type of structure and leadership their ICU will need to accomplish its mission. Typically, ICUs have been structured along the lines of tertiary, large community, and small community hospitals. These hospitals have different aims and goals and differing capacities to respond to acuity in the care of patients. Likewise, most ICUs have a designated ICU director with roles and responsibilities commensurate with those goals. Standards of care for typical arrangements have been described in the literature.4 An essential function of ICU administration is to determine and specifically articulate the ICU’s compliance with these standards.

The Present-Day Critical Care Landscape

Surveys of critical care delivery in the United States date back to the early 1990s.5,6 Reports of the supply and demand of adult critical care were most recently completed in 2000 through a joint effort on behalf of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM).7 Estimates on current and future requirements for adult critical care and pulmonary medicine physicians in the United States were reported by the Committee on Manpower for the Pulmonary and Critical Care Societies (COMPACCS). Angus and coworkers, on behalf of the COMPACCS group, extended their inquiry in 2006 to profile the organization and distribution of ICU patients and services in the United States.8

In response to the COMPACCS study report, an analysis was requested by the U.S. Senate. In 2006 a report to Congress from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Services and Resource Administration (HSRA) updated the findings in COMPACCS, reiterating their projections with respect to the critical care workforce.9 The HSRA workforce analysis indicated that the growth and aging of the population alone will increase demand for adult intensivist services by at least 38% between 2000 and 2020. Similarly, critical care nursing availability remains woefully inadequate to meet the demand. Proactive recruitment and retention strategies are paramount to maintain high-quality nursing care (Box 70.1).

The shortfall in supply of intensivists may drive administrators to consider an alternative critical care delivery team model, which may include nonintensivist physicians and physician extenders. Consideration to hopitalists partnering with intensivists as an option to fill the gap in intensivist supply is being addressed by two task forces, first in a publication of the 2004 Framing Options for Critical Care in the United States (FOCCUS) report and second in 2007 Prioritizing the Organization and Management of Intensive Care Services in the United States (PrOMIS) Conference Report.10,11 Reports from these task forces made three recommendations in an attempt to address the situation: to include (1) uniform protocols for intensive care treatment, (2) a process for certification of physicians providing critical care services with a competency assurance process, and (3) health service research with a focus on outcomes of ICU patients cared for by hospitalists.12 In another model, use of physician extenders may include physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). Limited research exists examining the use of NPs and PAs in the critical care setting with the majority focused on their impact on patient care management. Despite the small sample sizes and limited studies, NPs and PAs have demonstrated enhanced patient flow, improved clinical and financial outcomes for mechanically ventilated patients, reduction in ICU and hospital length of stay, and improved management in the heart failure patient population.13 Because the lack of intensivist staffing is unlikely to change significantly over the next few years, alternative models may be on the horizon.

Regardless of the expected reductions in available staffing, calls for increased access to intensivists continue with a goal of increasing intensivist coverage in-house around the clock. Despite the challenge by one recent study,14 multiple studies have demonstrated mortality rate and cost-savings benefits to critically ill patients receiving care by intensivists. Young and Birkmeyer estimated that in the context of 360,000 deaths occurring each year in ICUs, 54,000 lives may be saved annually with intensivist staffing.15 Similarly, Pronovost and colleagues have estimated that more than $5 billion could be saved annually.16 A report generated for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) notes that these benefits alone underestimate the potential improvement in the quality of care in terms of fewer complications, avoiding inappropriate utilization, decreased patient suffering, and better end-of-life care.17

The Leapfrog Group, a consortium of companies that purchase health care for their employees, convened in an effort to leverage their purchasing power to improve the quality of care. This powerful group has focused on improving four key areas central to patient safety and to cost containment in health care: (1) the use of computerized physician order entry, (2) the oversight of critical care physicians in the care of ICU patients, (3) the use of evidence-based hospital referral systems, and (4) Leapfrog safe practice scores.18 The influence of this group on both payers and health systems alike has contributed to the increasing demand for intensivists to care for critically ill patients. Unfortunately, the 2006 update to the COMPACCS study suggests that this need has gone essentially unmet. Loosely defining Leapfrog-compliant intensivist coverage for 80% of critically ill patients and the presence of 24-hour in-house physician coverage, Angus and colleagues found that only one in four ICUs had 80% intensivist coverage and that half had no intensivist coverage. Very few hospitals provided in-house physician coverage during off hours: 20% during weekend days, 12% during weekday nights, and 10% during weekend nights. Overall, only 4% of adult ICUs in the United States appeared to meet even a liberal interpretation of Leapfrog standards.8

Idealized Design for Critical Care Practice

A key first step is to halt further deterioration in present practice through effective coordination and communication to mitigate further erosion in practice standards (Boxes 70.2 and 70.3). Strategies to refine critical care delivery and meet predicted needs are present in the literature. Retaining tactics that have proved effective in trauma care are essential in building on current designs to streamline access to critical care. Hospital systems will need to collaborate on the care of critically ill patients in order to distribute critical care equitably as a resource, a social commodity. Finally, a realignment of values among health care leaders to build and reinforce a culture of efficiency, safety, and continuous improvement may stave off mediocrity.

Rational Model for Critical Care Delivery

Delivery of critical care should attempt to balance the needs of the community with access to the highest quality critical care services within that area. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) set the precedent for national practice standards for specific sets of critically ill patients when trauma centers were organized. When patients sustain injury with possible trauma, their care is initiated at appropriate trauma centers, depending on readiness and capacity to deliver care. Each designated level of classification (levels I to IV) has associated standards designated by the ACS. The structure has redefined the care of trauma patients and has been associated with improved outcomes and decreased mortality rates.19,20

Advancement in critical care delivery is feasible using a similar approach. The American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM) of the SCCM has developed a system to segregate hospitals into specific categories based on readiness and capacity to deliver critical care services (Box 70.4). These guidelines were first published in 1999 and revised in 2003.4 Appropriate application of these guidelines provides a gateway in developing collaborative relationships and to ensure a streamlined approach to critical care delivery.

Although the ACCM guidelines set the stage for ideal function of hospitals within each classification, a substantial performance gap between compliance with the guidelines and actual practice remains. Administrators should define their mission, thereby determining the range of services that their hospital seeks to effectively offer patients. Instrumental aspects to consider include the population the hospital serves, services provided by neighboring hospitals, and subspecialties of the staff physicians. Other factors that may be informative in redesign include a list of common diagnoses and acuity level in patients who are routinely treated.4

The specific standards that define level I and level II care are summarized in Box 70.5. Many hospitals will not be able to maintain these standards, and overlap with level II or level III critical care facilities may be considerable. Level II hospitals capable of providing comprehensive care for most diagnoses should attempt to emulate the level I guidelines for most conditions. For instance, a level II institution may not have the resources for optimal treatment of severe burns, but that facility may provide excellent surgical, cardiac, and posttransplantation medical care. Such a facility should aim to meet level I standards for conditions other than severe burns.

For level II or III institutions, a critical requirement of the guidelines is to establish agreements for transfer of patients for higher levels of care. It should be a usual practice in such facilities to stabilize patients with the intention to invoke established agreements to transfer to collaborating facilities.21 Although completing transfers may be routine for ICU staff, the requirement for agreements established in advance with collaborating institutions to accept transfers may be novel. In order to develop the efficiencies that will be necessary in the emerging critical care environment, these types of prenegotiated arrangements will be necessary to ensure access to needed care.

Committing the national critical care infrastructure to reorganization in line with the ACCM guidelines will not shield critical care providers and their patients from evolving demographic and market forces. However, by advancing institutions’ understanding of their own critical care infrastructure, needs, and capacity, and by establishing agreements for transfer between hospitals, the initiative will facilitate the movement toward regionalization of care. A study commissioned by the SCCM in 1994 suggested that regionalization of critical care services probably is beneficial to patients, in part by promoting access to larger academic institutions and resources, increasing subspecialty availability, and providing expertise in the care of the critically ill.22

In trauma systems, studies suggest that considerable efficiencies have been obtained with regionalization. Both mortality rates and hospital lengths of stay have decreased.19,23 Transition to level I ACS status has incurred increased costs at some centers, whereas other centers indicate that certification reduced costs.24,25 Beyond the financial impact of regionalization, the transition to a regional trauma system has promoted interhospital cooperation and promoted more effective resource utilization.26,27

Financial Modeling of Critical Care

The need for a transition to more rational structures in the provision of critical care services implies that hospitals will require an accurate accounting of costs and revenues as changes are made. Additionally, ICU quality improvement programs rely on an accurate understanding of costs to measure benefit (or harm) from programs intended to improve the quality of care. Several financial models exist to assess costs in the ICU.28,29 A given hospital’s cost accounting system may determine whether the ICU is viewed as generating a profit or a loss. Traditional methods have focused on the ICU as a cost center but not as a venue that may be revenue generating.30 Even in cases in which an ICU may always represent a net loss of revenue for an institution, understanding the revenue streams can permit optimization and diminish losses.

State of Critical Care Reimbursement

The federal Healthcare Financing Administration, which formerly administered Medicare and Medicaid, was renamed in 2001 the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS). Data from CMS’s Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) database remain the single best public source to support understanding of the financial horizon for hospital administrators. Contributing 30% of annual payments to hospitals in 2002, Medicare is the single largest payer in the U.S. health care system.1

Using the MEDPAR database, Cooper and Linde-Zwirble analyzed all hospital admissions during 2000 to determine the incidence, cost, and payment for ICU services.2 Their findings suggested that more than one fifth of all Medicare cases had an ICU stay with a cost to hospitals of nearly three times as much as floor patients—$14,135 versus $5571. However, ICU cases were paid at a rate only twice that of floor cases—$11,704 versus $5835. This means that only 83% of costs were paid for ICU patients, compared with 105% for floor patients, generating an annual $5.8 billion loss to hospitals when ICU care is required.

Halpern and Pastores describe recent patterns of critical care medicine (CCM) use and costs in the United States from 2000 to 2005. The study analyzed data from the Hospital Cost Report Information System. Results indicate the number of acute care hospitals decreased by 20.6%, hospital beds decreased by 4.2%, yet CCM beds increased by 6.5%. Fifty-two percent to 56% of insurance coverage is attributed to Medicare and Medicaid for both CCM and hospital days. Data show that the critical care payer mix is evolving with an increase in Medicaid recipients using CCM services. The results show the percentage of CCM days by Medicare decreased by 3.8% compared to an increase of 15.5% by Medicaid. From 2000 to 2005 the CCM cost per day rose 44.2% (from $2698 to $3518). With an increase in uninsured and underinsured, development of a plan to understand the impact of the Medicaid population should be considered during strategic planning.3

Focus on Expenditures and Revenues

Reducing services is a flawed method to contain costs, however, because the fixed costs (and some variable costs) associated with the provision of critical care remain high and the differential savings achieved by limiting access to these services is small. Typically, direct patient care costs can be accounted to individual patients whose care generated those costs, and indirect patient care costs are averaged across all patients admitted to critical care. The indirect costs are not reduced when access to available services is limited. Reliable savings stem from elimination of services, rather than limiting access to or frequency of utilization of services.31

The development of cost-cutting methods may be further understood in evaluating the various regions of the United States in overall spending differences. Data from the Dartmouth Atlas Project in five U.S. hospital regions from 1992 to 2006 found annual Medicare spending growth rates range from 2.3% to 5% per capita.32 Understanding this wide range in expenditures in areas with similar technologic and health care access may influence regions/hospitals with higher spending to develop more efficient and effective services.

Critical Care as a Product Line

Organizing a business plan for the critical care division, Bekes and colleagues30 isolated the major sources of critical care patients and their relative profit or loss for the division. Analysis via the customary cost accounting methods employed by the hospital demonstrated hospital-to-hospital transfers appeared to produce a majority of the revenue. Focusing on this source of revenue as a unique “product line” enabled these clinician-investigators to promote these services more widely in the surrounding community.

Critical Care Quality Improvement

Background

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies published a landmark report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The National Academies bring together committees of experts in all areas of scientific and technologic endeavor to address critical national issues and give advice to the federal government and the public. The IOM report was widely hailed as groundbreaking in view of its documentation of the ways in which the health care system harms patients. Some of the findings about the American health care system included the following: (1) tremendous gaps exist between medical knowledge and practice; (2) adverse events harm patients far too often; (3) too many people do not get the care they need; and (4) the system propagates waste by permitting fragmentation of care and utilization inefficiencies.33 In To Err Is Human, the IOM also estimated that despite incurring costs that are 40% greater than those for the next most expensive nation in terms of health care, 44,000 to 98,000 Americans die each year as a result of errors in their health care.

In 2003, in an exhaustive review of nearly 7000 patient charts across all regions of the United States, McGlynn and colleagues reported that the average defect rate, defined as the percent of cases in which care consistent with 439 indicators of quality was not delivered, approached 45% nationally.34 Stated otherwise, patients receive the care indicated slightly more than one half of the time. These investigators concluded that the deficits identified in adherence to recommended processes for basic care posed a continuing immediate danger to the health of the American public.

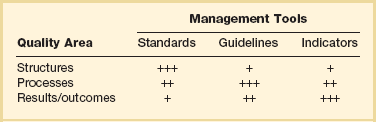

Donabedian Framework

Building on work begun by Donabedian, the IOM published Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century in 2001. The report outlined fundamental changes that must be made in order to improve health care in the United States. Donabedian had described three components of quality care—structure, process, and outcome—each of which must be addressed to effectively control and manage quality in health care settings.35 He proposed that each overarching concept of control should be monitored using specific tools (Table 70.1). The IOM report also refined Donabedian’s seven attributes of high-quality health care, proposing instead six primary aims: safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity.36

Table 70.1

Relations Between Quality Areas and Management Tools with Their Relative Importance

Reproduced from Frutiger A, Moreno R, Carlet J, et al for the Working Group on Quality Improvement of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine: A clinician’s guide to the use of quality terminology. Intensive Care Med 1998;24:860-863.

Quality Improvement Landscape

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Funding for health services research is achieved primarily through grant applications to the AHRQ. Lucian Leape and Donald Berwick report that the Center for Quality Improvement and Safety, a division of AHRQ, has emerged as a leader in education, training, convening agenda setting workshops, disseminating information, developing measures, and facilitating the setting of standards.37 AHRQ supports and funds efforts to evaluate best practices, medical errors, and development of patient safety indicators. The agency also has articulated an agenda that promotes the advancement of evidence-based best practices.

In 2001, Congress appropriated $50 million in annual funding for general patient safety research through AHRQ. Within 3 years these funds were assigned to an information technology focus. Leape and Berwick, key health care quality opinion leaders, lamented that this initial funding and subsequent reversal both legitimized health services research and at the same time starved these new researchers of the ability to undertake additional efforts.37 Although investigator-initiated research funding has declined, the previous work of sentinel studies has changed the face of health care. AHRQ’s funding in 2009 was allocated to compare alternative treatments for health conditions, reduce threats to patient safety, and advance health information technology.38

The Joint Commission

The Joint Commission (JC), formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), evaluates and accredits nearly 15,000 health care organizations and programs in the United States. The Commission, commonly misunderstood to be a governmental agency, is an independent not-for-profit organization. This body seeks to continuously improve the safety and quality of care provided to the public through the provision of health care accreditation and support for services that foster performance improvement in health care organizations.39

In 2003, after NQF’s publication of evidence-based safe practices, the JC required hospitals to implement 11 of these practices.40 The JC also has taken a special interest in developing a set of ICU core measures that are at present part of its library of supplemental measures.41 Reserve measures, unlike the core measures previously proposed by the JC to satisfy its ORYX* performance measurement requirements for accreditation, are available for hospitals that are seeking a set of voluntary measures to monitor ICU care.

The ICU JC reserve measures included six measures:

ICU 1: Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) prevention—patient positioning

ICU 2: Stress ulcer disease (SUD) prophylaxis

ICU 3: Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis

ICU 4: Central line–associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) rate

ICU 5: ICU length of stay, risk-adjusted

ICU 6: Hospital mortality rate for ICU patients, risk-adjusted42

Reporting of the JCAHO ICU core measures was stopped July 1, 2005, after a decision was taken to align the measure set with those under development at CMS and a new entity, the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP). SCIP is a collaboration among CMS, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and more than 20 surgical organizations. Under this arrangement, JCAHO has agreed to refocus the ICU reserve measures to apply primarily to surgical care. Ultimately, once these standards are evaluated and approved through the NQF consensus process, they will satisfy ORYX performance measurement standards.43

Alignment of Efforts

The alignment of forces interested in promoting evidence-based standards of care has led to efforts to establish a single set of applicable measures for hospitals. Although NQF appears to remain the ultimate clearinghouse for the endorsement of national standardized measures, the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA) has been instrumental in decreasing fragmentation in the development of national measures for quality of care. The HQA is a public-private collaboration including the CMS, the American Hospital Association, the Federation of American Hospitals, and the Association of American Medical Colleges. The HQA is supported by the AHRQ, NQF, JCAHO, American Medical Association, American Nurses Association, National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions, Consumer-Purchaser Disclosure Project, AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations), AARP, and U.S. Chamber of Commerce.44

The Leapfrog Group: Purchasers and Payers

The Leapfrog Group is a coalition of more than 160 large private employers and public purchasers that joined in 2000 to obtain leverage in health care purchasing decisions for employees. The group aims to “leapfrog” over key barriers as goals of their purchasing directives in order to overcome the poor value in the health care marketplace.45

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Campaign results include 65 hospitals reporting close to a year or more without a VAP and 35 hospitals close to a year or more without a CLASBI. Success across states includes a reported 42% reduction in CLASBI and a 70% reduction in pressure ulcers in 150 organizations across New Jersey. 46

Sponsored Statewide and Integrated Health System Collaboratives

As a national quality agenda has become better articulated, several critical care quality improvement projects have emerged at the state level. In Michigan, for instance, the Michigan Health and Hospital Association’s (MHA) Keystone Center for Patient Safety & Quality was created in March 2003. In collaboration with patient safety experts at Johns Hopkins University, MHA launched Keystone: ICU, which enjoys the participation of at least 120 ICUs and 70 hospitals. Johns Hopkins University and MHA estimate that the Keystone: ICU project saved 1574 lives, more than 84,000 ICU days, and greater than $175 million.47,48 This initiative has been expanded to other states such as New Jersey and Rhode Island. Group purchasing organizations such as Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Premier, Inc. have launched similar national initiatives in critical care quality improvement available to their membership.

Pay for Performance and Quality Reporting

Agencies dedicated to critical care quality improvement have had a significant interest in linking quality of care to pay-for-performance. The concept is not a new one as private and public insurers, health care purchasing organizations, and quality improvement thought leaders have pressed for the establishment of pay-for-performance plans to drive the market toward meeting evidence-based standards.49,50 Although guidelines were established to ensure the fairness of pay-for-performance plans, most recognize the inevitable increase in such initiatives.51,52

Pay for performance has been variously described. One iteration refers to direct payments to physicians from hospitals, or less commonly from insurers, as a reward for high-quality performance. For example, the most recent general practitioner contract in the United Kingdom includes 146 performance measures across seven areas of practice. This contract rewards performance in accordance with the measures with financial incentives.53 First-year results were recently reported: physicians exceeded projections of their performance and achieved a mean of 91% compliance with clinical guidelines. This resulted in payments estimated at $700 million more than expected.54 Despite the seeming success of this program, there is no means to detect whether physicians’ compliance efforts also may have detracted from quality in unmeasured patterns of care.55

Although pay for performance can contribute to improvements in quality of care it may present ethical concerns, whereby clinicians may become focused on scores and the need to meet the quality measure and potentially lose sight of the whole patient.56 Consideration of plans toward minimizing potential harm through quality measures and public reporting may likely contribute to the transition from quality to payment. Maximizing the CCM team efforts in proactive quality improvement initiatives may be the most effective approach to capitalize on making overall care better.57

Specific Quality Improvement Interventions in Critical Care

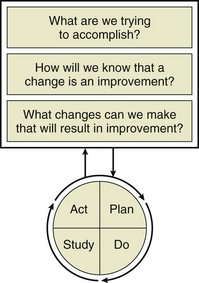

Shewart Model for Process Improvement

Critical care quality improvement initiatives typically have been executed in the setting of collaborative efforts as initially championed by the IHI and adapted by other groups. The precise mechanisms of implementation for these initiatives vary, but most sponsored quality improvement initiatives encourage the use of small-scale experiments to test new ideas. The principle calls for organizations to make the process of scientific prediction a part of routine work and was first advanced in 1931 by Walter Shewart, a pioneer in industrial quality control. Shewart advocated the use of iterative “plan-do-check-act” (PDCA) cycles to systematically test new ideas, evaluate their results, and, if successful, implement them.58 More recently, the IHI has advocated a similar structure known as the Model for Improvement59 (Fig. 70.1).

Decreasing Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Rates

Reducing mortality risk due to VAP requires an organized process that guarantees the early recognition of pneumonia along with the uniform and consistent application of the best evidence-based practices. Despite variability in clinical definitions to establish valid criteria to diagnose VAP, institutions have devoted considerable effort to combating VAP rates. The most recent evidence suggests the selection of diagnostic criteria may be irrelevant to outcomes. The CDC, however, has offered a clinical definition of VAP that has been widely adopted by the quality organizations cited earlier.60

Between July 2002 and January 2004, multidisciplinary improvement teams from 61 health care organizations participated in an IHI collaborative that included use of the ventilator bundle. Thirty-five of these teams consistently collected data on ventilator bundle element adherence and VAP rates. An average 44.5% reduction in the incidence of VAP was observed in these groups.61 Sixteen units were medical-surgical ICUs, in which the average VAP rate decreased from 5.5 to 2.7 cases per 1000 ventilator days.61 By comparison, the nationwide VAP rate for medical-surgical ICUs reported by the CDC for the January 2002 to June 2003 period was approximately 6.0 per 1000 ventilator days.62

Decreasing Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infection Rates

In an effort similar to that for decreasing VAP rates, decreasing CLABSIs has been a national priority in critical care quality improvement. The CDC has produced a standard measure that defines prevention of these infections as part of the National Healthcare Safety Network’s (NHSN) patient safety component protocol.60

A typical approach to preventing CLABSIs has been advocated by the IHI and includes four elements of care: proper hand hygiene, use of chlorhexidine for skin antisepsis, routine application of maximal barrier precautions, and optimal site selection. In 2004, Berenholtz and colleagues reported that in using a similar strategy, the rate of CLABSIs fell from 11.3 to 0 per 1000 catheter days.63 These results were estimated to have prevented 43 catheter-related bloodstream infections, 559 additional days in the ICU, and 8 deaths.63 Cost savings were estimated to be $1,824,447.63

Deploying Rapid Response Teams

The rapid response team (RRT)—sometimes referred to in the literature as a medical emergency team (MET)—is a team of nurses and other health care professionals (respiratory therapists, pharmacists, emergency department personnel, and others) who bring critical care expertise to the bedside. The teams may or may not include physicians. The essential concept is intervening to prevent harm when nursing staff is urgently concerned about a patient’s well-being. The key goal is to act before “failure to rescue” occurs and a patient has suffered a cardiac or respiratory arrest.64

The evidence supporting RRT adoption is mixed. Nevertheless, many hospitals have detected the need to have such a team to respond to urgent patient issues when physicians or housestaff may not be readily available. Several facilities that have implemented RRTs have reported a reduction in cardiac arrests and deaths, as well as a reduction in ICU and hospital bed days among survivors of cardiac arrest.65–67 Despite these findings, a single comprehensive negative trial has been published on the effects of MET/RRTs. Eleven hospitals functioned as usual, and 12 introduced a MET system. The investigators concluded that although the introduction of the MET system led to an increase in calls to the team, it did not substantially affect the incidence of cardiac arrest, unplanned ICU admissions, or unexpected death.68

Resuscitation and Treatment for Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock

Unique among projects to improve the quality of care for critically ill patients, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) was formed in 2003 with the joint cooperation of the SCCM, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), and the International Sepsis Forum (ISF). Evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock were published in 2004 with an updated version published in 2008 and a second revision scheduled for publication in early 2012.69,70 Partnering with the IHI, the SSC transformed into a global performance improvement program to extend the campaign guidelines to the bedside.71 The campaign included the development of sepsis bundles, educational material, recruitment of sites and local physician and nurse champions, launch meetings, and a secure database for data collection and outcome measures. Campaign results from 15,022 subjects at 165 international sites report a significant increase in bundle compliance and unadjusted mortality rate decrease from 37% to 30.8% over a 2-year period.72

Establishing Multidisciplinary Rounds

Experience with applying multidisciplinary rounds suggests that although initial meetings may be wide-ranging and unstructured, they can become a vital adjunct to patient care. Specifically, they provide an opportunity for disciplines to share their knowledge of patient care needs and focus the entire care team on common goals. Surveys of institutional perceptions of the state of safety in ICUs have led to the establishment of multidisciplinary rounds.73 These rounds are a mainstay of the effort to change the culture of ICUs from compartmentalized care based upon a single discipline’s knowledge to a more holistic approach integrating the talents of the many services caring for critically ill patients.74

Assessing Daily Patient Goals

All patients admitted to a 16-bed surgical oncology ICU were eligible for inclusion. The outcome variables assessed were ICU length of stay and percent of ICU residents and nurses who understood the goals of care for patients in the ICU. Baseline measurements were compared with measurements of understanding after implementation of a daily goals form. At baseline, less than 10% of residents and nurses understood the goals of care for the day. After implementing the daily goals form, greater than 95% of nurses and residents understood the goals of care for the day. After implementation of the ICU Daily Goals Worksheet, ICU length of stay decreased from a mean of 2.2 days to 1.1 days.75

Practice Management-Clinician-Family Communication

Protocols, guidelines, and toolkits have improved process and outcomes in numerous areas of critical care. Application of these techniques to advance communication with family members of the critically ill are interdependent upon a partnership between clinicians and family members, which is frequently not a recognized goal.76 Discussions with family members geared toward establishing treatment goals are important in promoting patient-family–centered care.

Clinician-family meetings are intended to share information related to the patient condition and prognosis and for the family to discuss care preference, family concerns, and goals of treatment.77 Early effective communication with patients and family members is imperative in shared decision making as they are an integral part of the care in the critically ill.

The American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004 to 2005 recognized the need for clinicians to develop a care plan and partner with patients and family members to improve outcomes.78 Family members often act as surrogate decision makers for the critically ill, which has been reportedly linked to anxiety, depression, and fatality. Methods to decrease stress include clinicians adapting to the family preference in decision making using a stepwise approach progressing toward improved decision making for the critically ill patient.76,79

Clinician-family conferences should be conducted within 72 hours of ICU admission. Preconferences have been suggested to improve the family experience with future conferences. Increased family satisfaction has been reported when clinicians spend more time listening than talking. Clinical-family communication has been summarized in a mnemonic and used as a framework for communication (Box 70.6). As part of an in interventional study reported by Lautrette and associates, application of the VALUE conference approach resulted in significant reduction in family symptoms of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder 90 days after the patient’s death.80 Use of printed information, staff champions, and consulting services are necessary resources to facilitate intensive communication.81 Documentation of the pertinent conference details and treatment goals are essential to assist future clinician-clinician and clinician-family communication throughout the patient’s ICU and hospital stay.

Open Versus Closed Intensive Care Units: Intensivist-Led Model

A prime example of a structural change (as in the Donabedian model described earlier) that may lead to improvement in the quality of care includes the establishment of an intensivist-led ICU service in medical ICUs. Although in other ICUs, such as neurosurgical units or pediatric units, it is commonly expected that the attending physician is an intensivist trained in that specialty, this has not been the rule in medical ICUs. Typically, mixed medical-surgical ICUs in the United States are “open” in that any physician on staff may admit patients to the ICU and write orders for care of that patient. A recent well-developed literature suggests that “closed” ICUs in which only medical intensivists care for medical patients may be associated with decreased morbidity and mortality rates and length of stay.82 Reorganizing ICU physician services in one organization by implementing an intensivist infrastructure has resulted in a 14% absolute risk reduction in mortality.83

Despite these findings, a number of barriers exist to adopting a “closed” model of care. These include excess inpatient bed capacity; reimbursement strategies that provide an incentive for nonintensivists to stay involved in ICU care; internal political barriers among the medical staff that hamper closure; and the growth of the hospitalist movement and an associated unwillingness to relinquish control of patients when admitted to the ICU. Some intensivists have adopted a “consultative” model, rather than providing 24-hour patient coverage.84

References

1. Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPAC). A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2005.

2. Cooper, LM, Linde-Zwirble, WT. Medicare intensive care unit use: Analysis of incidence, cost, and payment. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:2247–2253.

3. Halpern, N, Pastores, SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000-20005: An analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2010; 38:65–71.

4. Haupt, MT, Bekes, CE, Brilli, RJ, et al. Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Guidelines on critical care services and personnel: Recommendations based on a system of categorization of three levels of care. Crit Care Med. 2003; 31:2677–2683.

5. Groeger, JS, Kalpalatha, KG, Strosberg, M, et al. Descriptive analysis of intensive care units in the United States. Crit Care Med. 1992; 20:846.

6. Groeger, JS, Kalpalatha, KG, Strosberg, M, et al. Descriptive analysis of intensive care units in the United States: Patient characteristics and intensive care unit utilizations. Crit Care Med. 1993; 21:279.

7. Angus, DC, Kelley, MA, Schmitz, RJ, et al. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: Can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA. 2000; 284:2762–2770.

8. Angus, DC, Shorr, AF, White, A, et al. Critical care delivery in the United States: Distribution of services and compliance with Leapfrog recommendations. on behalf of the Committee on Manpower for Pulmonary and Critical Care Societies (COMPACCS). Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:1016–1024.

9. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Services and Research Administration, The critical care workforce: A study of the supply and demand for critical care physicians. Health Services and Research Administration, Washington, DC, 2006. ftp://ftp. hrsa. gov/bhpr/nationalcenter/criticalcare. pdf

10. Ewart, GW, Marcus, L, Gaba, MM, et al. The critical care medicine crisis: A call for federal action; a white paper from the critical care professional societies. Chest. 2004; 125:1518–1521.

11. Barnato, A, Kahn, JM, Rubenfeld, GD, et al. Prioritizing the organization and management of intensive care services in the United States: The PrOMIS conference. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35:1103–1111.

12. Heisler, M. Hospitalists and intensivists: Partners in caring for the critically ill—The time has come. J Hosp Med. 2010; 5:1–3.

13. Kleinpell, RM, Ely, EW, Grabenkort, R. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the intensive care unit: An evidence-based review. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36:1888–2897.

14. Levy, MM, Rapoport, J, Lemeshow, S, et al. Association between critical care physician management and patient mortality in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 148(11):801–809.

15. Young, M, Birkmeyer, J. Potential reduction in mortality rates using an intensivist model to manage intensive care units. Eff Clin Pract. 2000; 3:284–289.

16. Pronovost, PJ, Waters, H, Dorman, T. Impact of critical care physician workforce for intensive care unit physician staffing. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001; 7:456–459.

17. Rothschild, JM. “Closed” intensive care units and other models of care for critically ill patients. In: Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. AHRQ Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 43. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 1999:413.

18. The Leapfrog Group. Available at www.leapfroggroup.org, 2012. [Last accessed on June 14].

19. Cayten, CJ, Quervalu, I, Agarwal, N. Fatality analysis reporting system demonstrates association between trauma system initiatives and decreasing death rates. J Trauma. 1999; 46:751–756.

20. Mullins, RJ, Veum-Stone, J, Hedges, JR, et al. Influence of a statewide trauma system on location and hospitalization and outcome of trauma patients. J Trauma. 1996; 40:536–546.

21. Guidelines Committee of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Association of Critical-Care Nurses Transfer Guidelines Task Force. Guidelines for the transfer of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1993; 21:931–937.

22. Thompson, DR, Clemmer, TP, Applefeld, JJ, et al. Regionalization of critical care medicine: Task Force Report of the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1994; 22:1306–1313.

23. Rutledge, R, Fakhry, SM, Meyer, A, et al. An analysis of the association of trauma centers with per capita hospitalizations and death rates from injuries. Ann Surg. 1993; 218:512–524.

24. Dailey, JT, Teter, H, Cowley, RA. Trauma center closures: A national assessment. J Trauma. 1992; 33:539–549.

25. DiRusso, S, Holly, C, Kamath, R, et al. Preparation and achievement of American College of Surgeons level I trauma verification raises hospital performance and improves patient outcome. J Trauma. 2001; 51:294–299.

26. Guss, DA, Meyer, FT, Neuman, TS, et al. Impact of a regionalized trauma system in San Diego County. Ann Emerg Med. 1989; 18:1141–1145.

27. Schwab, W, Frankel, HL, Rotondo, MF, et al. The impact of true partnership between a university level I trauma center and a community level II trauma center of patient transfer practices. J Trauma. 1998; 44:815–819.

28. Noseworthy, TW, Konopad, E, Shustack, A, et al. Cost accounting of adult intensive care: Methods and human and capital inputs. Crit Care Med. 1996; 24:1168–1172.

29. Edbrooke, DL, Stevens, VG, Hibbert, CL, et al. A new method of accurately identifying costs of individual patients in intensive care: The initial results. Intensive Care Med. 1997; 23:645–650.

30. Bekes, CE, Dellinger, RP, Brooks, D, et al. Critical care medicine as a distinct product line with substantial financial profitability: The role of business planning. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1207–1214.

31. Roberts, RR, Frotos, PW, Ciavarella, GG, et al. Distribution of variable vs. fixed costs of hospital care. JAMA. 1999; 281:644.

32. Fisher, ES, Bynum, JP, Skinner, JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs—Lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2012; 360:849–852.

33. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine: To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1999.

34. McGlynn, EA, Asch, SM, Adams, J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:2635–2645.

35. Donabedian, A. Aspects of Medical Care Administration: Specifying Requirement for Health Care. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1973.

36. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

37. Leape, LL, Berwick, DM. Five years after To Err Is Human: What have we learned? JAMA. 2005; 293:2384–2390.

38. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/about/fy09glance.htm, 2012. [Last accessed June 17].

39. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Joint Commission facts. Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/AboutUs/joint_commission_facts.htm, 2006. [Last accessed Sept. 18].

40. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Joint Commission announces national patient safety goals. Available at http://www.jcaho.org/news_room/latest_from_jcaho/npsg.htm, 2002. [Last accessed Dec. 3].

41. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Joint Commission measure reserve library. Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/MeasureReserveLibrary/Spec+Manual+-+ICU.htm, 2006. [Last accessed Sept. 18].

42. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Specifications manual for national hospital quality measures—ICU. Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/F9F58E03-D7EB-40CF-9189-4243273F6ff5/0/ICUManualPDF.zip, 2006. [Last accessed Sept. 18].

43. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. ICU notification. Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/9A4EB4A8-B229-4A5F-AF28-F14D9961C113/0/ICUNotificationtomeasurementsystems.pdf, 2005. [Last accessed July 1].

44. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital quality alliance. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HospitalQualityInits/15_HospitalQualityAlliance.asp, 2006. [Last accessed Sept. 18].

45. Galvin, RS, Delbanco, S, Milstein, A, et al. Has the Leapfrog group had an impact on the health care market? Health Aff (Millwood). 2005; 24:228–233.

46. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 5 million lives campaign. Available at http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/PastStrategicInitiatives/5MillionLivesCampaign, 2012. [Last accessed March 12].

47. Available at. http://www.leapfroggroup.org/about_us/how_leapfrog_works, 2005 [Last accessed July 28].

48. Robeznieks, A. ICU effort saved lives, money: Organizers. More than 70 hospitals took part in the Keystone: ICU program. Mod Health Care. 2005; 35:16.

49. Berwick, DM, DeParle, NA, Eddy, DM, et al. Paying for performance: Medicare should lead. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003; 22:8–10.

50. Fong, T. Unfulfilled potential. More performance pay would improve care: NCQA. Mod Health Care. 2004; 34:12.

51. Pilonero, T. JCAHO performance pay guidelines hard to meet. Health Care Strateg Manage. 2005; 23(1):13–15.

52. Romano, M. AMA sets some ground rules. Detailed conditions outlined for pay-for-performance. Mod Health Care. 2005; 35:17.

53. Eggleston, K. Multitasking and mixed systems for provider payment. J Health Econ. 2005; 24:211–223.

54. Galvin, R. Pay-for-performance: Too much of a good thing? Health Aff. 2006; 25:w412–w419.

55. Newhouse, JP. Pricing the Priceless: A Health Care Conundrum. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002.

56. Snyder, L, Neubauer, RL, American College of Physician Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee. Pay-for-performance principles that promote patient-centered care: An ethics manifesto. for the. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 147:792–794.

57. Kahn, JM. Linking payment to quality—Opportunities and challenges for critical care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 184:491–502.

58. Shewart, W. Economic Control of Quality of Manufactured Product. Milwaukee, WI: ASOC Quality Press; 1980.

59. Langley, GL, Nolan, KM, Nolan, TW, et al. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996.

60. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Patient Safety Component Protocol, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at http://www.azhha.org/public/uploads/CDC%20PS%20Protocol.pdf. [Last accessed Dec. 25, 2006].

61. Resar, R, Pronovost, PJ, Haraden, C, et al. Using a bundle approach to improve ventilator care processes and reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia. Jt Comm J Qual Safety. 2005; 31:243–248.

62. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report. Data summary from January 1992 through June 2003, issued August 2003. Am J Infect Control. 2003; 31:448–498.

63. Berenholtz, SM, Pronovost, PJ, Lipsett, PA, et al. Eliminating catheter-related bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:2014–2020.

64. Hillman, K, Parr, M, Flabouris, A, et al. Redefining in-hospital resuscitation: The concept of the medical emergency team. Resuscitation. 2001; 48:105–110.

65. Buist, MD, Moore, GE, Bernard, SA, et al. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: Preliminary study. BMJ. 2002; 324:387–390.

66. Bellomo, R, Goldsmith, D, Uchino, S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003; 179:283–287.

67. Priestley, G, Watson, W, Rashidian, A, et al. Introducing critical care outreach: A ward-randomised trial of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2004; 30:1398–1404.

68. Hillman, K, Chen, J, Cretikos, M, et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 365:2091–2097.

69. Dellinger, RP, Carlet, JM, Masur, H, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:858–873.

70. Dellinger, RP, Levy, MM, Carlet, JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36(1):296–327.

71. Levy, MM, Pronovost, PJ, Dellinger, RP, et al. Sepsis change bundles: Converting guidelines into meaningful change in behavior and clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32(Suppl 11):S595–S597.

72. Levy, MM, Dellinger, RP, Townsend, SR, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2010; 38(2):367–374.

73. Pronovost, PJ, Weast, B, Holzmueller, CG, et al. Evaluation of the culture of safety: Survey of clinicians and managers in an academic medical center. Qual Safety Health Care. 2003; 12:405–410.

74. Vazirani, S, Hays, RD, Shapiro, MF, et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary communication and collaboration on physicians and nurses. Am J Crit Care. 2005; 14(1):71–77.

75. Pronovost, P, Berenholtz, S, Dorman, T, et al. Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care. 2003; 1871–1875.

76. Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. Physicians and family caregivers: A model for partnership. JAMA. 1993; 269:1282–1284.

77. Gay, EB, Pronovost, PJ, Bassett, RD, Nelson, JE. The intensive care unit family meeting: Making it happen. J Crit Care. 2009; 24:629.

78. Davidson, JE, Powers, K, Kedayat, KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35:605–622.

79. Curtis, JR, White, DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008; 134:835–843.

80. Lautrette, A, Darmon, M, Megarbane, B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:469–478.

81. Scheunemann, LP, McDevitt, M, Carson, SS, et al. Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care: A systematic review. Chest. 2011; 139:543–554.

82. Pronovost, PJ, Angus, DC, Dorman, T, et al. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: A systematic review. JAMA. 2002; 288:2151–2162.

83. Pronovost, P, Berenholtz, S. A Practical Guide to Measuring Performance in the Intensive Care Unit. Research Series, Vol. 2. Irving, TX: Veterans Health Administration; 2002.

84. Gipe, B. ICU administration. In: Parrillo JE, Dellinger RP, eds. Critical Care Medicine: Principles of Diagnosis and Management in the Adult. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1560.