Chapter 10. Integument

Rationale

Assessment of the integument, or skin, should be an integral part of every health assessment, regardless of setting or situation. Many common pathophysiologic disorders have associated integumentary disorders. For example, many contagious childhood diseases have associated characteristic rashes. Rashes of all sorts are common in childhood. The integument yields much information about the physical care that a child receives and about the nutritional, circulatory, and hydration status of the child, which is valuable in planning health teaching interventions.

Anatomy and Physiology

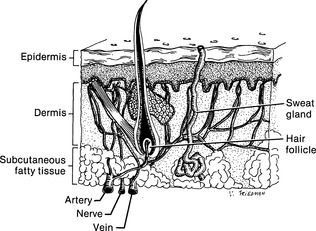

The skin, which begins to develop during the eleventh week of gestation, consists of three layers (Figure 10-1). The epidermis is the outermost layer and is further divided into four layers. The top layer, or horny layer (stratum corneum), is of primary importance in protecting the internal homeostasis of the body. Melanin, produced by the regeneration layer of the epidermis, is the main pigment of the skin. The dermis underlies the epidermis and contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, hair follicles, and nerves. Subcutaneous tissue underlies the dermis and helps cushion, contour, and insulate the body. This final layer contains sweat and sebaceous glands. The sebaceous glands produce sebum, which can have some bactericidal effect.

|

| Figure 10-1Normal skin layers.(From Potter PA, Weilitz PB: Pocket guide to health assessment, ed 5, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

The normal pH of the skin is acidic, which is thought to protect the skin from bacterial invasion. In infants the pH of the skin is higher, the skin is thinner, and the secretion of sweat and sebum is minimal. As a result, infants are more prone to skin infections and conditions than older children and adults. Further, because of loose attachment between the dermis and epidermis, infants and children tend to blister easily.

Preparation

Inquire about a family history of skin disorders, the lifestyle of the family (diet, bathing, use of soaps and perfumes, sun exposure), recent changes in lifestyle, and use of jewelry and medications. Ask when lesions began and whether other symptoms accompanied the lesions. Ask the parent to describe the size, configuration, distribution, type, and color of the lesions. Inquire about home remedies.

Assessment of Skin

Assessment of the skin is usually performed during assessment of each body system.

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Observe the skin for odor. | Clinical Alert |

| The presence of odor can indicate poor hygiene or infection. | |

| Observe the color and pigmentation of the skin. If a color change is suspected, carefully inspect the areas of the body where there is less melanin (nailbeds, earlobes, sclerae, conjunctivae, lips, mouth). Inspect the abdomen (an area less exposed to sunlight) and the trunk. Use natural daylight for assessment if jaundice is suspected. Pressing a finger against a skin area produces blanching, which supplies contrast and enables closer assessment of the presence of jaundice. Note location, distribution, and pattern of color changes. If a child has a different pigmentation from that of the accompanying parent, ask about the absent parent for hereditary trait recognition. |

Overall skin color normally varies between and within races and affects assessment findings.

Clinical Alert

A brown color to the skin can indicate Addison’s disease or some pituitary tumors.

A reddish-blue skin tone suggests polycythemia in light-skinned children.

Red skin color can result from exposure to cold, hyperthermia, blushing, alcohol, or inflammation (if localized). Skin redness is more difficult to detect in dark-skinned children and assessment needs to be augmented by palpation and assessment of skin temperature.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

|

Blue (cyanosis) coloration of nails, soles, and palms can indicate peripheral or central cyanosis. Peripheral cyanosis can arise from anxiety or cold; central cyanosis is indicative of a marked drop in the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and is best identified in the lips, tongue, and oral mucosa. Generalized body cyanosis can be evident in central cyanosis. Dark-skinned children might appear ashen-gray or pale with cyanosis, and lips and tongue might appear ashen-gray or pale. Yellow-green to orange skin color can indicate jaundice (which accompanies liver disease, hepatitis, red cell hemolysis, biliary obstruction, or severe infection in infants) and is best observed in the sclerae, mucous membranes, fingernails, soles, palms, and on the abdomen. In dark-skinned children, jaundice can appear as yellow staining on the palate, palmar surfaces, or sclerae.

Yellowing of the palms, soles, and face (and not of the sclerae or mucous membranes) can indicate carotenemia, produced from ingestion of carrots, squash, and sweet potatoes.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

|

Yellowing of the exposed skin areas (and not of the sclerae and mucous membranes) can indicate chronic renal disease.

Bruising in soft tissue areas (e.g., buttocks) rather than on shins, knees, or elbows can indicate child abuse or cultural practices such as spooning that are used to heal.

A generalized lack of color involving the skin, hair, and eyes indicates albinism.

Symmetric white patches indicate vitiligo.

Café-au-lait or light brown spots and axillary or inguinal freckling that develops in infancy or early childhood can indicate neurofibromatosis.

Pallor (lack of pink tones in fair-skinned children; ash-gray or yellow-brown color in dark-skinned children), suggestive of syncope, fever, shock, edema, or anemia, is best observed in the face, mouth, conjunctivae, and nails.

|

|

|

Observe the moistness of exposed skin areas and mucous membranes.

Lightly stroke body creases. Compare body creases to one another.

|

The skin is normally slightly dry. Exposed areas normally feel dryer than body creases. Mucous membranes should be moist.

Clinical Alert

Dry skin on the lips, hands, or genitalia suggests contact dermatitis.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Generalized dryness, accompanied by moist body creases and moist mucous membranes, indicates overexposure to the sun, overbathing, or poor nutrition. Dry arm creases and mucous membranes suggest dehydration. Clamminess can indicate shock or perspiration. | |

| Palpate the skin with the back of the hand to determine temperature. Compare each side of the body with the other, and the upper with the lower extremities. |

Clinical Alert

Generalized hyperthermia can indicate fever, sunburn, or a brain disorder. Localized hyperthermia can indicate burn or infection.

Generalized hypothermia can indicate shock. Local hyperthermia can indicate exposure to cold. Coolness in hands and feet with pallor and cyanosis might suggest Raynaud’s phenomenon.

|

| Inspect and palpate the texture of the skin. Note the presence of thickening, scars, and excessive scar tissue (keloid). |

An infant’s or child’s skin is normally smooth and even.

Clinical Alert

Rough, dry skin can indicate overbathing, poor nutrition, exposure to weather, or an endocrine disorder and is associated with Down syndrome.

Flaking or scaling between the fingers or toes can be related to eczema, dermatitis, or a fungal infection.

Thin, dry, wrinkled skin can indicate ectodermal hypoplasia.

Oily scales on the scalp indicate seborrheic dermatitis (cradle cap).

|

| Assessment | Findings | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Scaly, hypopigmented patches on the face and upper body, or scattered papules (Table 10-1) over the arms, thighs, and buttocks, and fine, superficial scales can indicate eczema.

Malar butterfly rash of cheeks (excluding the nasolabial folds) and maculopapular rashes occurring on sun-exposed skin, especially in an adolescent, can be indicative of lupus erythematosus.

Thickened and enfolded areas of the skin can suggest neurofibromatosis. Moist, warm, flushed skin occurs with hyperthyroidism.

A crackling sensation on palpation can indicate subcutaneous emphysema.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Palpate for turgor by grasping a fold on the upper arm or abdomen between the fingers and quickly releasing. Note the ease with which the skin moves (mobility) and returns to place (turgor) without residual marks. |

Skin normally returns quickly to place with no residual marks.

Clinical Alert

A skinfold that returns slowly to place or retains marks commonly indicates dehydration or malnutrition. Other possible causes are chronic disease and muscle disorders.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Palpate for edema by pressing a thumb into areas that look swollen. |

Clinical Alert

Thumb indentations that remain after the thumb is removed indicate pitting edema.

Edema in the periorbital areas can indicate crying, allergies, recent sleep, renal disease, or juvenile hypothyroidism.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assessment | Findings | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edema (dependent) of the lower extremities and buttocks can indicate renal or cardiac disorders. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

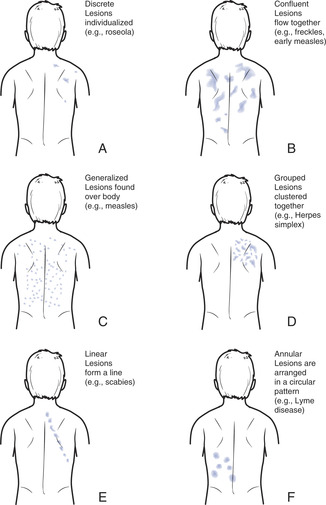

| Inspect and palpate the skin for lesions (see Table 10-1). Note the distribution or arrangement of lesions (Figure 10-2), shape, color, size, and consistency of the lesions and birthmarks (Table 10-3). |

Clinical Alert

Rashes are associated with several childhood disorders (Table 10-2).

Petechiae and ecchymoses can indicate a bleeding tendency.

A painful, nonpruritic, maculopapular rash over the trunk is found in some instances of West Nile virus.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Enquire about pruritus. |

Clinical Alert

Itching can indicate the onset of an asthmatic attack or can occur with hepatitis A or renal disorders or with some skin disorders (itching is particularly associated with eczema or atopic dermatitis, head lice, or scabies).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inspect nails for color, shape, and condition. |

Clinical Alert

Clubbing can indicate chronic respiratory or cardiac disease.

Convex or concave curving nails can be hereditary or related to injury, iron deficiency, or infection.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

|

Yellow or white coloration in a thickened nailbed can indicate a fungal infection of the nail (onychomycosis), which can occur with cosmetic nail applications.

A transverse furrow in the nail can indicate acute infection, anemia, or malnutrition.

Splinter hemorrhages (small, dark linear formations) in nailbeds can indicate subacute bacterial endocarditis or mitral stenosis.

|

|

| Inspect nails for nail biting, skin picking, infection. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Assess hair for distribution, color, texture, amount, and quality. Hair distribution is useful in estimating sexual maturity. | Hair normally covers all but the palms, soles, inner labial surfaces (girls), and prepuce and glans penis (boys). |

| Assess hair for dandruff and nits. If nits are suspected, use a fine-toothed metal or electronic comb on the hair to differentiate between nits, dandruff, and lint. |

Scalp hair is normally shiny, silky, strong.

Clinical Alert

Dry, brittle, or depigmented hair can indicate nutritional deficiency or thyroid disorder.

A hairline that extends to mid-forehead can be normal or can indicate cretinism.

Delayed or absent hair growth can indicate an ectodermal dysplasia.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

|

Unusually fine hair that is unable to hold a wave can indicate hyperthyroidism.

Alopecia (loss of hair) can be related to tinea capitis, compulsive hair pulling, tight hairstyles (e.g., ponytails, corn braids), abuse, or persistent positioning on one side (in infants).

Hair tufts on the spine or buttocks can indicate spina bifida.

White eggs that are firmly attached to hair shafts indicate head lice. Dandruff can be removed.

|

Pain: related to itching, loss of skin surface.

Hyperthermia: secondary to illness.

Knowledge deficit (hygienic needs, prevention of infection, prevention of scarring): related to cognitive limitations, lack of exposure, lack of interest in learning, information misinterpretation.

Sleep deprivation: related to discomfort.

Risk for infection: related to broken skin, exposure to pathogens.

Altered oral mucous membrane: secondary to infection, dehydration, medication side effects, malnutrition or vitamin deficiency.

Altered parenting: related to lack of knowledge about child maintenance.

Chronic low self-esteem: related to presence of acne, birthmarks, scarring.

Impaired tissue integrity: related to injury, infection, nutritional disorders, altered pigmentation, alterations in turgor.

Impaired tissue integrity: related to mechanical injury, infection, nutritional deficit, chemical factors, developmental factors, fluid volume deficit or excess, impaired physical mobility, infection, altered circulation, knowledge deficit, irritants.