27 Insomnia

Definitions and epidemiology

Insomnia refers to difficulty in either falling asleep, remaining asleep or feeling refreshed from sleep. Complaints of poor sleep increase with increasing age and are twice as common in women as in men (Sateia and Nowell, 2004). Thus, by the age of 50, a quarter of the population are dissatisfied with their sleep, the proportion rising to 30–40% (two-thirds of them women) among individuals over 65 years.

Pathophysiology

Sleep systems

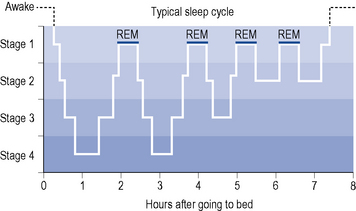

Orthodox sleep normally takes up about 75% of sleeping time. It is somewhat arbitrarily divided into four stages (1–4) which merge into each other, forming a continuum of decreasing cortical and behavioural arousal (see Fig. 27.1). Stages 3 and 4 represent the deepest phase of sleep and are also termed slow-wave sleep (SWS).

Aetiology and clinical manifestations

Insomnia may be caused by any factor which increases activity in arousal systems or decreases activity in sleep systems. Many causes act on both systems (Morin, 2003). Increased sensory stimulation activates arousal systems, resulting in difficulty in falling asleep. Common causes include chronic pain, gastric reflux, uncontrolled asthma and external stimuli such as noise, bright lights and extremes of temperature. Anxiety may also delay sleep onset as a result of increased emotional arousal.

Frequent arousals from sleep are associated with myoclonus, ‘restless legs syndrome’, muscle cramps, bruxism (tooth grinding), head banging and sleep apnoea syndromes. Reversal of the sleep pattern, with a tendency for poor nocturnal sleep but a need for daytime naps, is common in the elderly, in whom it may be associated with cerebrovascular disease or dementia. In general, decreased duration of sleep has been shown to increase the risk of obesity (Kripke et al., 2002) and hypertension (Gangwisch et al., 2006). Sleep disturbances in the elderly are also associated with increased falls, cognitive decline and a higher rate of mortality (Cochen et al., 2009). There is growing concern that daytime sleepiness resulting from insomnia increases the risk of industrial, traffic and other accidents.

Treatment

Non-drug therapies

Explanation of sleep requirements, attention to sleep hygiene (see Box 27.1), reduction in caffeine or alcohol intake and the use of analgesics where indicated may obviate the need for hypnotics (Anon, 2004). Medications that cause insomnia should also be avoided if possible. Psychological techniques such as relaxation therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) are also helpful (Kierlin, 2008). However, studies comparing psychological approaches to hypnotics are scarce (Riemann and Perlis, 2009).

Hypnotic drugs

Benzodiazepines

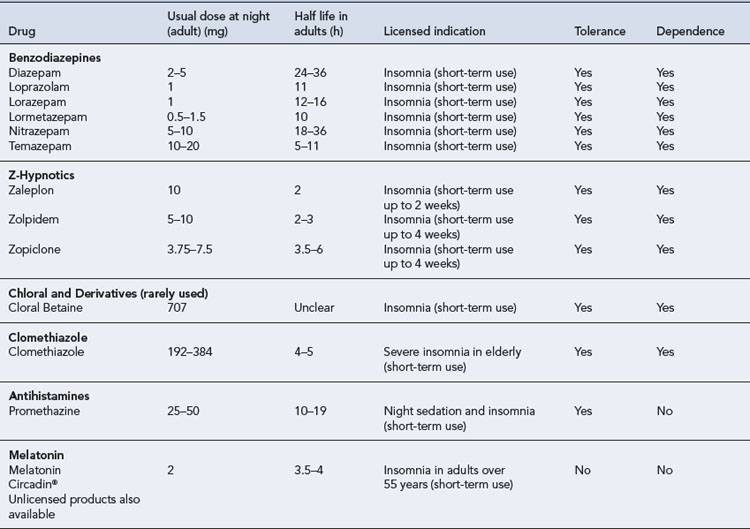

By far the most commonly prescribed hypnotics are the benzodiazepines. A number of different benzodiazepines are available (see Table 27.1). These drugs differ considerably in potency (equivalent dosage) and in rate of elimination but only slightly in clinical effects. All benzodiazepines have sedative/hypnotic, anxiolytic, amnesic, muscular relaxant and anticonvulsant actions with minor differences in the relative potency of these effects.

Pharmacokinetics

Most benzodiazepines marketed as hypnotics are well absorbed and rapidly penetrate the brain, producing hypnotic effects within half an hour after oral administration. Rates of elimination vary, however, with elimination half-lives from 6 to 100 h (see Table 27.1). These drugs undergo hepatic metabolism via oxidation or conjugation and some form pharmacologically active metabolites with even longer elimination half-lives. Oxidation of benzodiazepines is decreased in the elderly, in patients with hepatic impairment and in the presence of some drugs, including alcohol.

Mechanism of action

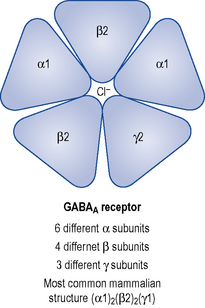

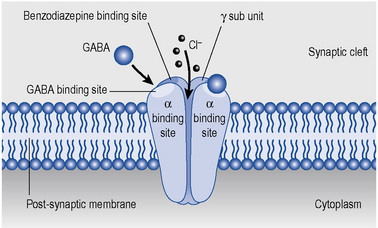

GABAA receptors are multi-molecular complexes (see Figs. 27.2 and 27.3) that control a chloride ion channel and contain specific binding sites for GABA, benzodiazepines and several other drugs, including many non- benzodiazepine hypnotics and some anticonvulsant drugs (Haefely, 1990). The various effects of benzodiazepines (hypnotic, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, amnesic, muscle relaxant) result from GABA potentiation in specific brain sites and at different types of GABAA receptor. There are multiple subtypes of GABAA receptor which may contain different combinations of at least 18 sub-units (including α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3 and others) and the subtypes are differentially distributed in the brain.

Benzodiazepines bind to three or more subtypes and it appears that their combination with α2-containing subtypes mediates their anxiolytic effects, α1-containing subtypes their sedative and amnesic effects, and α1 as well as α2 and α5 their anticonvulsant effects (Rudolph et al., 2001).

Zopiclone

In 1988, zopiclone, a cyclopyrrolone, was the first non-benzodiazepine to be approved for the treatment of insomnia in the European market. Although classed as a non-benzodiazepine, it still binds to benzodiazepine receptors but is said to be more selective for the α1 subtype. It has hypnotic effects similar to benzodiazepines and carries a similar potential for adverse effects including tolerance, dependence and abstinence effects on withdrawal. Psychiatric reactions, including hallucinations, behavioural disturbances and nightmares, have been reported to occur shortly after the first dose. Other common adverse reactions include a bitter taste, a dry mouth and difficulty arising in the morning (Zammit, 2009). This drug appears to have no particular advantages over benzodiazepines, although it may cause less alteration of sleep stages and does not have the controlled drug requirements of the benzodiazepines. Eszopiclone the S- (+) isomer of zopiclone is available in the USA but there are no current plans to launch in the UK. What advantage, if any, the isomer incurs over zopiclone is unclear.

Zolpidem

Zolpidem is an imidazopyridine that binds preferentially to the α1 benzodiazepine receptor sub-unit thought to mediate hypnotic effects. It is an effective hypnotic with only weak anticonvulsant and muscle relaxant properties. As it has a short elimination half-life (2 h) hangover effects are rare but rebound effects may occur in the later part of the night, causing early morning waking and daytime anxiety. High doses have been reported to cause brief psychotic episodes, tolerance and withdrawal effects. Anecdotal case reports (mainly from the USA) have associated zolpidem with complex sleep related behaviours. These have included ‘sleep-driving’, making phone calls, preparing food and eating while asleep. The majority of these cases also involved ingestion of alcohol and should be interpreted with caution because they are not replicated in the wider medical literature (Zammit, 2009). A controlled release version of zolpidem (zolpidem-CR) is available in some countries.

Zaleplon

Zaleplon is a pyrazolopyrimidine which, like zolpidem, binds selectively to the α1 benzodiazepine receptor. It is an effective hypnotic, has a very short elimination half-life (1 h) and appears to cause minimal residual effects on psychomotor or cognitive function after 5 h. There is little evidence of tolerance or withdrawal effects in short-term use and the drug appears suitable for use in the elderly (Doble et al., 2004).

All the ‘Z-hypnotics’ are recommended for short-term use only (2–4 weeks) and are more expensive than benzodiazepines. There is no compelling evidence to distinguish them from the shorter acting benzodiazepine hypnotics (National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004). Patients who do not respond to either a benzodiazepine or z-hypnotic should not be prescribed the other.

Melatonin

Melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone, produced by the pineal gland, which regulates the circadian rhythm of sleep. It begins to be released once it becomes dark, and continues to be released until the first light of day. Melatonin release decreases with age which may in-part explain why older adults require less sleep. Melatonin supplementation promotes sleep initiation and helps to reset the circadian clock allowing uninterrupted sleep. It has also been shown to improve next day functioning. Contrary to most other hypnotics melatonin shows no abuse or tolerance potential and appears to have no next day sedation problems. Prolonged release melatonin (Circadin®) was launched in June 2008 and is available at a dose of 2 mg at night for up to 3 weeks. It is licensed as monotherapy in primary insomnia for adults over 55 years old. Whilst the adverse effect profile looks advantageous there are currently no trials comparing melatonin against psychological or other hypnotic treatments. Circadin® is also much more expensive than other currently prescribed hypnotics (Anon, 2009).

Other hypnotic drugs

The risk of adverse effects, including dependence and dangerous respiratory depression in overdose, generally outweighs the potential benefits of the older hypnotics, chloral derivatives, clomethiazole and barbiturate. Therefore, these drugs are best avoided. Antidepressants with sedative properties, such as amitriptyline, mirtazapine, trazodone and agomelatine may be helpful if sleep disturbance is secondary to depression. Sedative antihistamines, such as promethazine, diphenhydramine and chlorphenamine, which can be purchased over-the-counter, have mild-to-moderate hypnotic efficacy but commonly produce hangover effects and rebound insomnia can occur after prolonged use (Anon, 2004).

Potential adverse effects of hypnotic use

Rebound insomnia

Rebound insomnia, in which sleep is poorer than before drug treatment, is common on withdrawal of benzodiazepines. Sleep latency (time to onset of sleep) is prolonged, intra-sleep wakenings become more frequent and REM sleep duration and intensity are increased, with vivid dreams or nightmares which may add to frequent awakenings. These symptoms are most marked when the drugs have been taken in high doses or for long periods, but can occur after only a week of low dose administration. They are prominent with moderately, rapidly eliminated benzodiazepines (temazepam, lorazepam) and may last for many weeks. With slowly eliminated benzodiazepines (diazepam), SWS and REM sleep may remain depressed for some weeks and then slowly return to the baseline, sometimes without a rebound effect. Tolerance and rebound effects are reflections of a complex homeostatic response to regular drug use, involving desensitisation, uncoupling and internalisation of certain GABA/benzodiazepine receptors and sensitisation of receptors for excitatory neurotransmitters (Allison and Pratt, 2003). These changes encourage continued hypnotic usage and contribute to the development of drug dependence.

Rational drug treatment of insomnia

A hypnotic drug may be indicated for insomnia when it is severe, disabling, unresponsive to other measures or likely to be temporary. In choosing an appropriate agent, individual variables relating to the patient and to the drug need to be considered (see Table 27.1).

Patient care

Type of insomnia

The elderly

A considerable number of elderly patients give a history of regular hypnotic use going back for 20 or 30 years. In many of these patients, gradual reduction of hypnotic dosage or even withdrawal may be indicated and can be carried out successfully, resulting in improved cognition and general health with no impairment of sleep or escalation of other symptoms (Curran et al., 2003).

Choice of drug

Duration and timing of administration

Answer

Mr PH’s downfall could have been averted at several stages.

Answers

Allison C., Pratt J.A. Neuroadaptive processes in GABAergic and glutamatergic systems in benzodiazepine dependence. Pharmacol. Ther.. 2003;98:171-195.

Anon. What’s wrong with prescribing hypnotics? Drug Ther. Bull.. 2004;42:89-93. Available at: http://dtb.bmj.com/content/42/12/89.full.pdf Accessed March 2010

Anon. Melatonin for primary insomnia. Drug Ther. Bull.. 2009;47:74-77. Available at: http://dtb.bmj.com/content/47/7/74.full.pdf Accessed March 2010

Cochen V., Arbus C., Soto M.E., et al. Sleep disorders and their impact on healthy, dependent and frail older adults. J. Nutr. Health. Aging. 2009;13:322-330.

Curran H.V., Collins R., Fletcher S. Older adults and withdrawal from benzodiazepine hypnotics in general practice: effects on cognitive function, sleep, mood and quality of life. Psychosom. Med.. 2003;33:1223-1237.

Doble A., Martin I.L., Nutt D. Calming the brain: benzodiazepines and related drugs from laboratory to clinic. London: Martin Dunitz; 2004.

Gangwisch J., Heymsfield S., Boden-Albala B., et al. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension. Hypertension. 2006;47:833-839.

Haefely W. Benzodiazepine receptor and ligands: structural and functional differences. In: Hindmarch I., Beaumont G., Brandon S., et al, editors. Benzodiazepines: Current Concepts. Chichester: John Wiley; 1990:1-18.

Kierlin L. Sleeping without a pill: non-pharmacologic treatments for insomnia. J. Psychiatr. Pract.. 2008;14:403-407.

Kripke D., Garfinkel L., Wingard D., et al. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:131-136.

Morin C.M. Treating insomnia with behavioural approaches: evidence for efficacy, effectiveness and practicality. In: Szuba M.P., Kloss J.D., Dinges D.F., editors. Insomnia: Principles and Management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003:83-95.

National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of Zaleplon, Zolpidem and Zopiclone for the short-term management of insomnia, Technology Appraisal 77.. London: NICE. 2004. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA77/Guidance/pdf/English Accessed March 2010

Riemann D., Perlis M.L. The treatments of chronic insomnia: a review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapies. Sleep Med. Rev.. 2009;13:205-214.

Rudolph U., Crestani F., Mohler H. GABAA receptor subtypes: dissecting their pharmacological functions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.. 2001;22:188-194.

Sateia M.J., Nowell P.D. Insomnia. Lancet. 2004;364:1959-1973.

Zammit G. Comparative tolerability of newer agents for insomnia. Drug Saf.. 2009;32:735-738.

Bloom H.G., Ahmed I., Alessi C.A., et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the assessment and management of sleep disorders in older persons: supplement. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.. 2009;57:761-789.

Parish J. Sleep-related problems in common medical conditions. Chest. 2009;135:563-572.

Sullivan S.S., Guilleminault C. Emerging drugs for insomnia: new frontiers for old and novel targets. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs. 2009;14:411-422.