Inpatient management of diabetes and hyperglycemia

1. Does evidence support intensive management of blood glucose in the hospital setting?

Although it is well established that hyperglycemia can lead to adverse patient outcomes, there is controversy over what degree of glycemic control is most appropriate. The largest randomized controlled trial (RCT), the Normoglycemia in Intensive Care Evaluation—Survival Using Glucose Algorithm Regulation (NICE-SUGAR) study, demonstrated a higher risk of mortality in patients with tight glycemic control (blood glucose [BG] target 81-108 mg/dL) than in those with standard glycemic control (BG target 144-180 mg/dL). The increase in mortality is thought to be partially due to the increase in hypoglycemia (≤ 40 mg/dL) seen in the intensively treated group. Although this study corroborated previous suggestions that glycemic control is important, it did underscore the risks of hypoglycemia and relaxing of glycemic targets.

2. What are the glycemic targets for the critically ill patient population?

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations are to initiate insulin therapy for treatment of hyperglycemia at a threshold of no greater than 180 mg/dL. Insulin therapy should then be titrated to maintain glycemic levels between 140 and 180 mg/dL. The glycemic goal can be further lowered to 110 to 140 mg/dL in select patients as long as it can be attained without hypoglycemia. It is further recommended that all patients entering the hospital undergo glucose testing to detect previously undiagnosed hyperglycemia that will require treatment.

3. What are the glycemic targets for non–critically ill patients?

There is only one RCT that examines the effect of glycemic control in non–intensive care unit (ICU) settings. The Randomized Study of Basal-Bolus Insulin Therapy in the Inpatient Management of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Undergoing General Surgery (RABBIT 2 Surgery trial) showed that a basal-bolus insulin regimen was associated with fewer hospital complications than sliding-scale insulin therapy in the general surgery population. In addition, a number of observational trials have shown an association between hyperglycemia and adverse events such as prolonged hospital stays, infection, and mortality. The ADA’s current recommendations are to maintain premeal blood glucose targets at less than 140 mg/dL and random BG values at less than 180 mg/dL. In patients with a history of tighter outpatient glycemic control, the target can be lowered with the avoidance of hypoglycemia.

4. What are the inpatient glycemic targets for pregnant patients?

Blood glucose goals for pregnancy are tighter than those for the general population. Hyperglycemia during pregnancy is associated with many adverse outcomes, including macrosomia, congenital abnormalities, fetal hyperinsulinemia, and fetal mortality. For patients with gestational diabetes, the recommendations are a fasting blood glucose level lower than 95 mg/dL, a 1-hour postmeal blood glucose of 140 mg/dL or less, and a 2-hour postmeal blood glucose level of 120 mg/dL or less. For patients with preexisting diabetes, the ADA recommends that premeal, bedtime, and nocturnal glucose levels remain between 60 and 99 mg/dL and that peak postmeal glucose levels remain between 100 and 129 mg/dL.

5. Which patients are at high risk for hyperglycemia during their hospital stay?

Numerous factors can lead to hyperglycemia in patients with and without a preexisting diagnosis of diabetes. These situations include initiation of glucocorticoid therapy, enteral or parenteral nutrition, immunosuppressive agents, and periods of increased metabolic stress. It is recommended that all patients undergo glucose monitoring if they are receiving therapy that may cause hyperglycemia. If hyperglycemia occurs, appropriate treatment should be given using glycemic goals consistent with those for someone with known diabetes. The ADA recommends that a hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) level be measured in all patients with diabetes admitted to the hospital if the results of testing in the previous 2 to 3 months are not available.

6. What is the best treatment for inpatient management of diabetes?

Insulin therapy, given as an intravenous (IV) infusion or subcutaneous injections, is the safest and most effective way to treat hyperglycemia in the hospital setting. Insulin is effective and can be rapidly adjusted to adapt to changes in glucose levels or food intake. It is also recommended that standardized insulin protocols be used whenever available.

7. What is an intravenous insulin infusion and why is it used in critically ill patients?

An intravenous insulin infusion is composed of 1 unit of regular human insulin per 1 mL of 0.9% NaCl (normal saline). When given intravenously, regular insulin has a rapid onset and short half-life, allowing for quick adjustment of insulin doses to achieve appropriate glycemic control.

8. At what rate should an insulin infusion be started?

An insulin infusion is usually initiated at 0.1 unit per kg body weight. Alternately, the starting dose can be based on the current blood glucose level, with rates varying from 1 to 7 units per hour depending on the severity of hyperglycemia. An initial bolus of regular insulin is also generally given if blood glucose levels are higher than 150 mg/dL at the start of the insulin infusion.

9. How should the IV insulin infusion rate be adjusted?

Insulin infusions should be adjusted on an hourly basis. Dosage adjustments should be made on the basis of the current glucose level and the rate of change from the previous glucose level. If the blood glucose levels do not change by 30 to 50 mg/dL within an hour, the insulin drip rate should be increased. Conversely, if glucose levels drop more than 30 to 50 mg/dL in an hour, the insulin drip rate should be reduced. Many insulin infusion protocols have been published and are available for use.

10. How do you transition a patient off an insulin infusion?

Because of the short duration of action of IV regular insulin, it is imperative to give subcutaneous basal insulin, long-acting or intermediate-acting, at least 2 hours or rapid-acting insulin 1 to 2 hours before discontinuation of the insulin infusion. To calculate the total daily dose (TDD) of subcutaneous insulin needed, add the amount of insulin given during the past 6 hours of the IV insulin infusion; multiply by 4 for an estimate of the 24-hour requirement; and then reduce that amount by 20% for a new TDD. This TDD should then be split as 50% to 80% basal insulin (higher amount if patient is fasting) and 20% to 50% bolus insulin.

11. How should you select a basal insulin dose?

Basal coverage can be achieved through the use of intermediate-acting insulin (NPH [neutral protamine Hagedorn] insulin) dosed twice daily or, preferably, long-acting insulin (glargine, detemir) dosed once or twice a day. Long-acting insulins generally provide more consistent coverage with minimal insulin peaks, whereas NPH insulin is more likely to cause hypoglycemia because of variable insulin action and peaks. Regardless of the type of insulin used, the basal insulin dose usually accounts for approximately 50% of the TDD of insulin.

12. How should you select a prandial dose for patients on insulin?

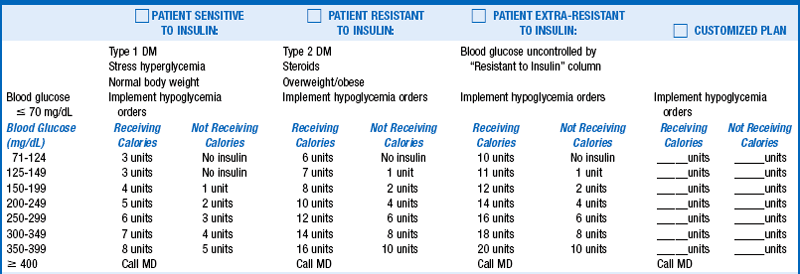

Prandial insulin should include both nutritional (meal coverage) and correctional (treatment of hyperglycemia) components. Rapid-acting insulin analogs (lispro, aspart, glulisine) should be given 0 to 15 minutes prior to meals, whereas short-acting insulin (regular) should be given 30 minutes prior to meals. Rapid-acting analogs provide greater flexibility in dosing and have a shorter duration of action, making them the preferred method of treatment. In general, the total bolus insulin doses each day should be about 50% of the TDD of insulin delivery. However, in the hospital setting a reduced prandial dose may be needed because of decreased appetite or variance in oral intake. Correction insulin dosing can be calculated on the basis of the patient’s insulin sensitivity. This insulin is either added to the nutritional dose or given alone if the patient is not receiving calories. For patients who have type 1 diabetes or who are insulin sensitive, a good starting point for correction dosing is 1 unit of insulin for every 50-mg/dL increase in BG above a goal of 100 mg/dL. For patients with type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance, 1 unit of insulin should be given for every 25-mg/dL increase above 100 to 150 mg/dL. (See Table 4-1 for example). To prevent hypoglycemia due to “stacking” of insulin, correction insulin doses should, in general, not be given more often than every 4 hours.

13. How should you adjust insulin dosages?

Glucose levels should be assessed on a daily basis. Basal insulin dosages are assessed mainly by review of fasting glucose levels. Blood glucose levels should remain relatively steady through the night. A significant rise or drop in glucose during the night would necessitate a change in basal insulin dosing. Prandial insulin is assessed by pre-lunch, pre-dinner, and bedtime values. For more precise prandial dosing, a 2-hour postprandial glucose check can be performed. It is expected that this postprandial value will be about 30 to 50 mg/dL higher than the preprandial reading.

14. Is “sliding-scale” insulin therapy still used?

Sliding-scale insulin therapy is not an effective treatment for hyperglycemia and therefore should not be used. The sliding scale in this approach was a set amount of bolus insulin, usually regular insulin, that was given to treat high blood glucose levels, generally more than 200 mg/dL. The insulin was given without thought as to meal times, previous dosages, carbohydrate content of meals, or the patient’s insulin sensitivity. This approach often resulted in a wide fluctuation of glucose levels because hyperglycemia was not treated preemptively but instead was treated after the fact.

15. What is hypoglycemia and how should it be treated?

Hypoglycemia is defined as a blood glucose level lower than 70 mg/dL, which is considered the initial threshold for counterregulatory hormone release. Patients at high risk for hypoglycemia include those with renal or liver failure, altered nutrition, and a history of severe hypoglycemia. Treatment of hypoglycemia is based on the patient situation. For a patient who is able to take oral treatment, 15 to 20 g of a quick-acting carbohydrate such as juice, regular soda, or glucose tablets is the preferred treatment. If unconscious or unable to take oral treatment, the patient can be given 25 g (½ ampule) of dextrose 50% intravenously or 1 mg of glucagon intramuscularly. The glucose level should be rechecked within 15 minutes of treatment to assess its efficacy. If the blood glucose level is still lower than 70 mg/dL, treatment should be repeated.

16. Are oral agents or noninsulin injectables appropriate to use in hospitalized patients?

There are limited data on the safety and efficacy of using oral agents or noninsulin injectables (glucagon-like peptide-1 [GLP-1] analogs, pramlintide) in hospital settings. In most cases of hyperglycemia, noninsulin treatment options can be effective in lowering blood glucose to goal levels, especially in acute illness. In general their use should be limited to patients who are eating regularly. Additionally, oral agents may be initiated or resumed in clinically stable patients in anticipation of discharge.

17. What is the best treatment for steroid-induced hyperglycemia?

Steroids impair insulin action, resulting in insulin resistance and diminished insulin secretion, which manifests largely as elevated postprandial blood glucose excursions. The extent of blood glucose elevation depends on the amount and duration of steroid therapy. Individuals who are on low doses of steroids and who are insulin naive may be treated with bolus insulin at mealtimes. If the patient is receiving higher doses of steroids or has a history of insulin-treated diabetes, a good treatment option is an intermediate-acting basal insulin, NPH insulin, dosed at the same time as administration of the steroid. Insulin needs should be assessed and adjusted with tapering or discontinuation of steroid therapy.

18. What is the best treatment for hyperglycemia with enteral or parenteral nutrition?

There are several approaches to insulin treatment for hyperglycemia with nutritional support. For total parenteral nutrition (TPN), the addition of regular insulin to the TPN bag is the safest approach to glycemic control. The initial dosing recommendation is 1 unit for every 10 to 12 g of dextrose in the TPN solution. The amount of insulin can be adjusted daily or an additional rapid-acting correction scale can also be used for immediate correction of hyperglycemia. Another approach to treatment is the use of a basal/bolus regimen. The latter poses an increased risk of hypoglycemia if TPN is unexpectedly discontinued or the TPN dextrose concentration is changed without adjustment of insulin dosing.

There are many approaches to treatment for enteral nutrition (EN). Basal insulin can be administered once or twice daily in combination with a rapid-acting insulin according to a correction scale every 4 to 6 hours. Alternatively, intermediate-acting 70/30 human insulin given every 8 hours with rapid-acting insulin according to the correctional scale every 4 hours is an approach that the authors use. Hypoglycemia is of immense concern in these patients, as feeding can be interrupted unexpectedly with dislodging of the feeding tube or discontinuation of the EN due to nausea or diagnostic testing. It is important to remember that these patients are in a consistent postprandial state and to adjust glucose goals accordingly.

19. Can a continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion be used in the inpatient setting?

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), also known as an insulin pump, can be safely used in the inpatient setting. It is imperative that the patient is mentally and physically able to operate his or her own insulin pump. It is also recommended that personnel with CSII experience help manage the patient. Current pump settings, including basal rates, bolus settings, and bolus dosages, should be documented on a daily basis.

20. How do you adjust diabetes medications prior to surgery?

Hypoglycemia is a considerable risk for patients undergoing surgery because of their NPO (nothing by mouth) status. Oral agents should be held the morning of the procedure. It is recommended that patients on long-acting insulin (glargine/detemir) therapy take about 80% of their normal dose the night before surgery. Patients on intermediate-acting insulin (NPH), therapy should take 50% of their typical dose the morning of the procedure. Correctional doses of rapid-acting analogs can be given in the perioperative periods every 4 hours to maintain glycemic levels below 180 mg/dL. If the procedure is prolonged or if prolonged NPO status is expected, the use of an insulin infusion is recommended.

21. How do you decide what home regimen to order at discharge?

If the patient has had good glycemic control as an outpatient, it is recommended that the patient be sent home on the regimen he/she was on previously. For the patient with a new diagnosis of diabetes or requiring a change in previous therapy due to poor glycemic control, recommendations should be based on the patient’s preference/ability as well as the cost of and contraindications to medications. It is also recommended that medication administration instructions, especially for insulin, be given in both oral and written formats and that details of discharge medications and instructions be communicated promptly and clearly also to the patient’s primary care provider.

, American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes 2012. Diabetes Care 2012;35:S36–S40.

Fowler, MJ. Inpatient diabetes management. Clinical Diabetes. 2009;27:119–122.

Magaji, V, Johnston, JM. Inpatient management of hyperglycemia and diabetes. Clinical Diabetes. 2011;29:3–9.

Moghissi, ES, Korytkowski, MT, DiNardo, M, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;33:1119–1131.

Van den Berghe, G, Wilmer, A, Hermans, G, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:446–449.

Umpierrez, GE, Hellman, R, Korytkowski, MT, et al, Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care setting. an Endocrine Society clinic practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:16–38.

Umpierrez, GE, Smiley, D, Jacobs, S, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing surgery. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:256–261.