87 Injuries to the Shoulder Girdle and Humerus

• Scapular fractures require high force and are therefore associated with a high percentage of injuries to the ipsilateral chest wall and lung.

• Posterior dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint may damage vital structures within the superior mediastinum and thorax.

• Proximal and middle third clavicle fractures and type I and type III distal third clavicle fractures should be treated by placement of an arm sling.

• Open clavicle fractures require urgent open reduction and internal fixation.

• The degree of acromioclavicular separation can be diagnosed from an acromioclavicular view radiograph taken with the patient in the sitting or standing position.

• Axillary nerve function, both sensory and motor, should be tested in all patients with glenohumeral dislocation.

• Most proximal humerus fractures, especially in older individuals, can be treated conservatively.

• Injuries to the radial nerve should always be considered in patients with midshaft humerus fractures.

• Supracondylar fractures in children, especially those with significant displacement, may be associated with injuries to the brachial artery and the median and radial nerves.

Pathophysiology

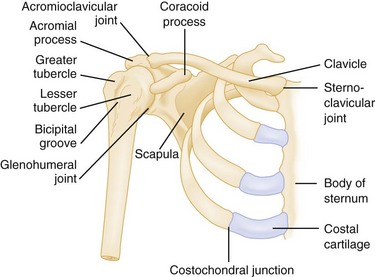

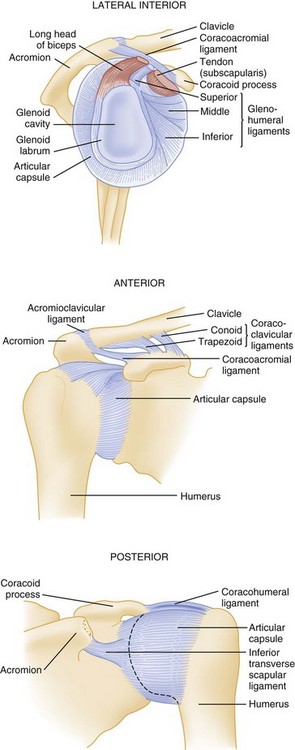

The scapula and clavicle are attached to the axial skeleton by ligaments at the sternoclavicular joint and by muscles from the blade or body of the scapula to the thorax. The clavicle is attached to scapula by the coracoclavicular and acromioclavicular ligaments. The coracoacromial ligament serves as the roof of the coracoacromial arch, beneath which the neurovascular bundle traverses (Figs. 87.1 and 87.2).

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Sternoclavicular Joint Sprains and Dislocations

These injuries are graded as type I, a simple sprain of the joint; type II, subluxation of the joint, either anterior or posterior; and type III, complete dislocation of the joint. Dislocation usually results from a lateral force applied to the shoulder and an indirect force applied to either a rolled-back shoulder (anterior dislocation) or a rolled-in shoulder (posterior dislocation). Posterior dislocations are potentially life-threatening because the dislocated medial head of the clavicle may cause pneumothorax or injuries to the great vessels, esophagus, or trachea (all structures in the superior mediastinum).1

The patient complains of severe pain in the affected sternoclavicular joint. In anterior dislocations, the protruding medial end of the clavicle is visible, easily palpable, and tender. In posterior dislocations, there is often a cavity where the medial end of the clavicle would normally lie, which is especially noticeable when compared with the uninjured side. Patients with posterior dislocations may also have signs and symptoms of pneumothorax, vascular occlusion, and esophageal or tracheal injury.2 Routine radiographs may not be diagnostic, and computed tomography (CT) is usually required to make the diagnosis. This should always be performed with intravenous (IV) contrast media when a posterior sternoclavicular dislocation is suspected to rule out injuries to the superior mediastinal vascular structures3 (Fig. 87.3).

Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocation or Separation

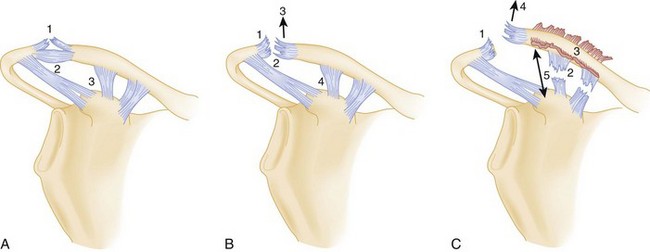

Acromioclavicular separations are generally caused by a fall onto the point of the shoulder or acromioclavicular joint with the arm adducted (thus the lay term shoulder pointer to describe this injury). It is caused less frequently by a fall onto the outstretched arm in extreme abduction, which drives the acromion below the clavicle. Acromioclavicular separations are classified as six types, although only the first three (I to III) are commonly seen. Types IV to VI are very uncommon and usually require surgical repair.1 In type I acromioclavicular separations, the acromioclavicular ligaments are partially torn and the coracoclavicular ligaments are intact, which results in less than 50% superior dislocation or separation of the clavicle from the acromion (Fig. 87.4, A to C). In type II injuries, the acromioclavicular ligaments are completely torn and the coracoclavicular ligaments are stretched or partially torn, which results in at least 50% superior dislocation or separation of the clavicle from the acromion. In type III injuries, both the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments are completely torn, with complete superior dislocation or separation of the clavicle from the acromion.

The patient complains of severe pain in the acromioclavicular joint. Type I dislocations are characterized by tenderness and some swelling over the acromioclavicular joint, with little or no tenderness over the distal end of the clavicle and coracoid process. With type II dislocations, patients have tenderness and more swelling over the acromioclavicular joint and some tenderness over the coracoid process. In type III dislocations, the clavicle is obviously dislocated superiorly when the patient is sitting or standing, with less deformity noted when the patient is supine. Shoulder radiographs may miss an acromioclavicular separation if the radiograph is taken with the patient supine. Acromioclavicular views (a single radiograph that includes both acromioclavicular joints) should be taken with patients in the sitting or standing position and the arms unsupported. In type I injuries there is less than 50% cephalad dislocation of the clavicle on the acromion of the affected shoulder. Type II injuries are marked by greater than 50% cephalad displacement of the clavicle on the acromion on the affected side. In type III dislocations, complete dislocation is seen on sitting or standing films. Use of weight-bearing films (the patient holds weights with the affected arm) is of no benefit.4

Clavicle Fractures

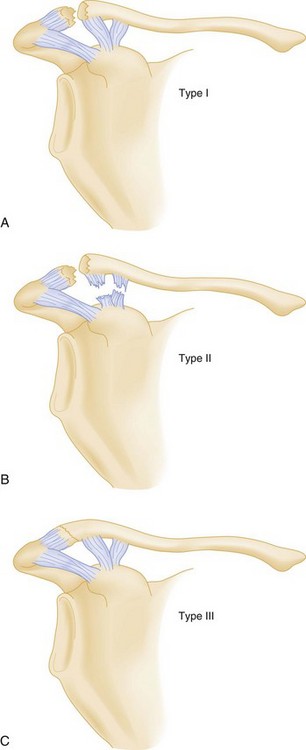

The most common mechanism of injury is a medially directed blow to the shoulder, usually from a ground-level fall. Children frequently have a bowing deforming or a greenstick fracture, whereas in adults the fracture fragments are often significantly displaced. Clavicle fractures are divided into proximal third, middle third, and lateral third. Lateral third fractures are divided into types I, II, and III (Fig. 87.5). Type II lateral third fractures are relatively unstable because the coracoclavicular ligament has been disrupted.

Scapula Fractures

Scapular fractures are typically associated with high-energy force and are thus often associated with significant life-threatening injuries, especially injuries to the ipsilateral ribs, pleura, and lungs. Most scapular fractures are caused by a direct blow, although fractures of the glenoid and scapular neck may occur as a result of a fall on an outstretched arm.5

Glenohumeral Dislocations

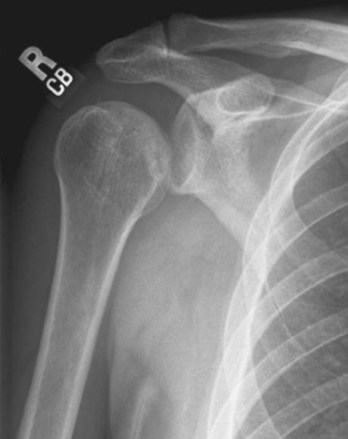

Patients generally have severe pain in the glenohumeral joint and hold the affected arm in adduction and internal rotation. There is lack of the normal contour, with a depression where the humeral head would normally reside. Patients report extreme pain in the joint with any attempted movement of the arm. Anteroposterior (AP) and axillary or transthoracic lateral radiographic views should be obtained in all patients with suspected dislocations, even if the patient has a history of multiple dislocations, because occasionally an associated fracture of the proximal end of the humerus or a posterior dislocation will be present.6,7 If displaced fractures of the glenoid or proximal end of the humerus are suggested on plain radiographs, CT scans of the shoulder should be obtained. Although the AP film usually shows the “light bulb” appearance of the humeral head, it is not always present (Fig. 87.6). Though rare, with luxatio the patient has the classic picture of holding the arm in marked adduction and over the head (Fig. 87.7). The radiograph reveals the humeral head to lie inferior to the glenoid and the humeral shaft adducted superiorly (Fig. 87.8).

Fig. 87.6 Anteroposterior shoulder radiograph of a patient with a posterior glenohumeral dislocation.

Proximal Humerus Fractures

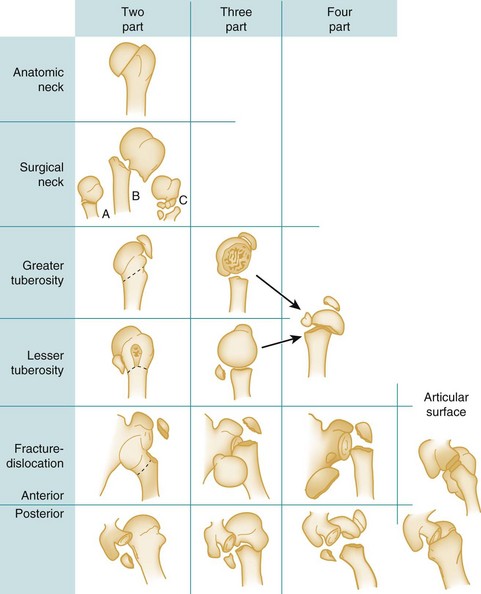

The Neer fracture classification is most commonly used and is based on the position of the articular segment, the greater and lesser tuberosities, and the humeral shaft. According to the Neer classification, a fracture is considered displaced if any major fracture fragment is displaced 1 cm or more or is angulated greater than 45 degrees.8 Fractures are classified as one-, two-, three-, or four-part fractures and are usually differentiated along the classic epiphyseal lines (anatomic neck, surgical neck, greater tuberosity, and lesser tuberosity) (Fig. 87.9).

The patient has severe pain in the proximal end of the humerus. An obvious deformity may be present, as well as swelling and extreme tenderness over the proximal end of the humerus. The trauma radiographic series recommended by Neer,8 as well as an AP internal rotation view and an axillary lateral view, provides the most complete diagnostic information. A CT scan of the shoulder may be necessary to better define the extent of injury.

Distal Humerus (Supracondylar) Fractures

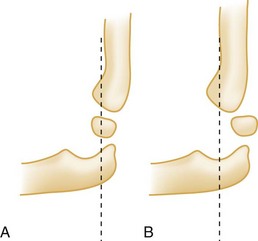

The patient is generally seen holding the injured arm in extension with the unaffected hand. Swelling, as well as tenderness to palpation over the distal end of the humerus, is typical. An S-shaped deformity may be present if significant displacement of the fracture fragments has occurred. The patient resists any attempt to flex or extend the elbow. Elbow radiographs (AP and lateral views) should be obtained. The fracture will often be visible only on the lateral view unless fracture fragments are significantly displaced. Normally, the anterior humeral line should pass through the capitellum (Fig. 87.10, A and B). If the capitellum is anterior to the anterior humeral line, it is diagnostic of a flexion-type supracondylar fracture in a child. If the capitellum is posterior to the anterior humeral line, it is diagnostic of an extension-type supracondylar fracture. Based on radiographic findings, extension fractures are often classified into three types: type I has minimal or no displacement; type II is a displaced fracture with the posterior cortex intact; and type III is a completely displaced fracture, with both the anterior and posterior cortices disrupted.

Rotator Cuff Tendinitis/subacromial Bursitis, Rotator Cuff Tears, and Impingement Syndromes

The patient complains of pain over the proximal end of the humerus, where the rotator cuff tendons attach to the greater tuberosity. Significant pain is felt with both active and passive abduction of the shoulder. In other impingement syndromes (supraspinatus tendinitis and subacromial bursitis), the symptoms are similar, but with less tenderness over the rotator cuff and greater tenderness proximally.9 The drop arm test is positive if a significant rotator cuff tear has occurred. The patient extends the injured arm to 90 degrees and the operator lightly taps the wrist or forearm. In a positive test, the patient suddenly drops the arm. In addition, the patient cannot slowly lower the arm from the abducted position—rather, it drops suddenly to the side. In patients with rotator cuff tendinitis or subacromial bursitis, significant pain occurs with abduction, but the drop arm test is negative.9

Tenosynovitis and Rupture of the Long Head of the Biceps Tendon

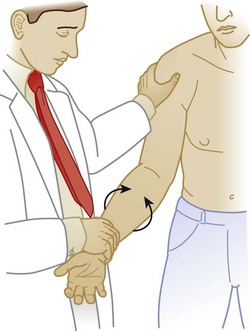

Pain in the anterior aspect of the shoulder may radiate to the elbow. The pain is made worse with abduction and external rotation. There is tenderness over the biceps tendon in the bicipital groove. The Yergason test is a reliable method for confirming the diagnosis of tenosynovitis of the long head of the biceps tendon. The patient’s elbow is flexed to 90 degrees and the patient tries to supinate the forearm against resistance. If this action causes increased pain in the bicipital groove, the test is positive10 (Fig. 87.11).

Adhesive Capsulitis

In most cases the nondominant arm is affected and the patient experiences pain with minimal activity. The pain is generally worse at night. There is tenderness in the subacromial area and marked limitation of glenohumeral motion in all ranges, especially abduction and rotation.9 The diagnosis is made primarily on the basis of the symptoms and signs described previously. Radiographs are typically normal. Arthroscopy or arthrography may be diagnostic, but these modalities are invasive and should be avoided if possible. Adhesive capsulitis is usually due to prolonged immobilization of the shoulder in patients with subacromial bursitis or rotator cuff tendinitis.

Treatment

Sternoclavicular Dislocation

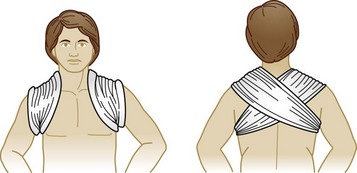

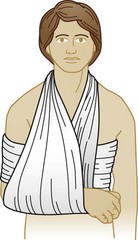

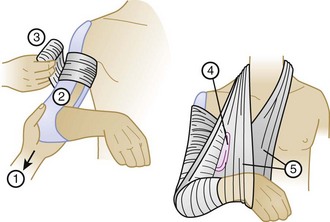

Closed reduction of an anterior dislocation is accomplished with the patient in the supine position and rolled blankets placed between the shoulder blades. Significant downward pressure on the distal and proximal ends of the clavicle with elevation of the proximal end usually reduces the dislocation (Fig. 87.12). If reduction is accomplished, the patient should be placed immediately in a clavicle or figure-of-eight splint to maintain the reduction (Fig. 87.13), as well as an arm sling and swath (Figs. 87.14 and 87.15). Patients with posterior sternoclavicular dislocations require immediate orthopedic consultation; open reduction is usually necessary. Most reductions should be performed in the operating room with thoracic surgery backup in the event of injury to the superior mediastinal structures. Complications include pneumothorax and vascular, esophageal, and tracheal injuries. Although nonoperative attempts at reduction are occasionally successful, most patients with posterior sternoclavicular dislocations require reduction in the operating room, especially to check for damage to the vital superior mediastinal structures.

Acromioclavicular Dislocation or Separation

Types I, II, and III acromioclavicular separation should initially be treated conservatively. In the emergency department (ED), the patient should be given adequate analgesia and have ice applied to the area of injury. Following diagnosis, the patient should wear a shoulder immobilizer, be instructed to apply ice to the injured area for 20 to 30 minutes every hour, and be given adequate oral analgesia. The more superiorly the clavicle is displaced in type II dislocations, the more likely patients are to benefit from surgical repair.11 Type IV, V, and VI injuries are generally severe, and these patients should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon for consultation because most will require open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF).

Clavicle Fractures

Almost all proximal third, middle third, and type I and III distal third fractures heal with conservative treatment (a sling or a sling and swath for the ipsilateral arm). Even markedly displaced fractures generally heal without surgical intervention. Some attempts at closed reduction may be appropriate if these fractures are markedly displaced or if significant skin tenting is noted. Many orthopedic surgeons believe that surgical intervention is indicated only if the fracture is open, if there is marked diastasis between the two fracture fragments that cannot be corrected with closed reduction, or in some cases of a type II distal clavicle fracture.12,13 Recently, one study showed that surgical repair of middle third clavicle fractures may be cost-effective after 9 years when compared with nonsurgical therapy.14 However, even type II distal third clavicle fractures may do well with nonoperative therapy,15 although nonunion occurs frequently and surgical therapy is probably preferred.

For patients with middle and proximal third fractures, a figure-of-eight clavicle splint may decrease the pain and, in occasional patients, help keep the fracture reduced. However, such splints are primarily for the patient’s comfort and should not be used if their application increases pain from the fracture, which it often does, especially with lateral third clavicle fractures. No evidence has shown any difference in healing time, severity, duration of pain, or any other parameter with an arm sling versus a figure-of-eight clavicle splint or both.16

Scapula Fractures

Most scapular fractures are treated nonsurgically with a sling, ice, analgesics, and range-of-motion exercises. Displaced fractures of the glenoid, neck, and coracoid and some acromial fractures may need ORIF; patients with such fractures should be referred for consultation with an orthopedic surgeon.2

Glenohumeral Dislocations

Anterior Dislocations

Multiple techniques for closed reduction of anterior glenohumeral dislocations have been recommended. The three main categories are scapular manipulation, traction, and leverage.17 The hippocratic method (foot in the axilla with traction on the extended arm) and the Kocher maneuver (traction, adduction, internal rotation) should not be used because of the increased incidence of brachial plexus injuries with the hippocratic method and the increased incidence of proximal humerus fractures with the Kocher maneuver. For almost all reduction techniques to be successful, adequate sedation/analgesia or anesthesia must be obtained. Conscious sedation with IV fentanyl (50 to 100 mcg) and IV midazolam (1 to 3 mg) is adequate for most reductions. However, some patients require deep sedation with propofol or etomidate, and occasionally a patient may require general anesthesia to accomplish the reduction. Frequently, injecting 10 to 20 mL of 1% lidocaine or 0.25% bupivacaine into the vacated glenohumeral joint will significantly facilitate reduction of the dislocation.18

Scapular Manipulation

Ideally, the patient is in the prone position with the dislocated arm hanging over the edge of the stretcher. Traction is applied to the arm, and the operator pushes the tip of the scapula medially while stabilizing the upper part of the scapula (Fig. 87.16). If the patient insists on sitting up, this same technique can be combined with a modified hippocratic method in which one operator applies countertraction superiorly with a sheet sling in the axilla, another operator places traction on the arm, and a third operator manipulates the scapula. This is the technique of choice for the author. It requires relatively little sedation or analgesia and is successful in more than 90% of cases.19

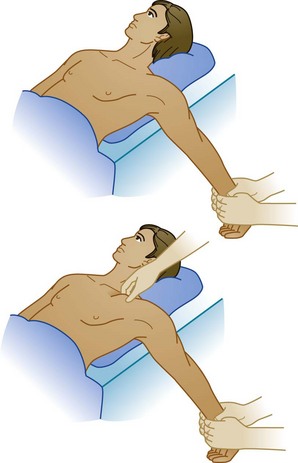

External Rotation

With the patient supine, the affected arm is adducted close to the thorax. The elbow is flexed to 90 degrees and the operator very slowly externally rotates the arm without applying longitudinal traction. This method is safe, easily learned, and relatively atraumatic for the patient20 (Fig. 87.17).

Modified Hippocratic (Traction-Countertraction) Method

With the patient supine, the elbow is slightly abducted and flexed to 90 degrees. The operator ties a sheet around his or her waist and to the proximal end of the patient’s forearm. An assistant slings another sheet around the thorax and under the affected armpit and ties it around his or her own waist. The operator and the assistant pull in opposite directions with their arms and bodies (Fig. 87.18).

Stimson Method

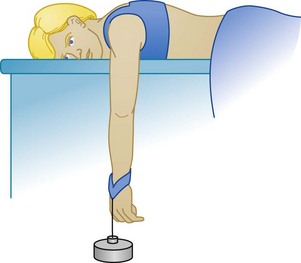

With the patient prone, the affected arm is dangled over the edge of the stretcher and a 10- to 20-lb weight is attached to the wrist to produce constant, gentle traction. This method is one of the oldest and has the advantage of not requiring the physician to be present for the reduction and probably being the least traumatic for the patient. The disadvantage is that it often takes 20 or more minutes to complete the reduction and ties up a nurse for this period if the patient has been consciously sedated (Fig. 87.19). Several other techniques have also been proposed for reduction of anterior glenohumeral dislocations.21–25

Posterior Dislocations

The most common technique for reduction of a posterior dislocation is to apply axial traction in line with the humerus while an assistant applies countertraction with a sheet slung under the axilla of the affected arm. Gentle pressure is applied by the operator, who also applies slow external rotation to the affected humerus (Fig. 87.20).

Luxatio Erecta (Inferior Dislocations)

If possible, orthopedic consultation should be obtained before reduction. The traction-countertraction method is most effective in reducing this dislocation, although deep sedation or general anesthesia may be required. Recently, a technique by which the luxatio erecta is converted to an anterior-inferior dislocation and then relocated in a separate step has been shown to be more successful and requires less analgesia and sedation.26

Proximal Humerus Fractures

With a glenohumeral dislocation, the patient will usually need ORIF to reduce the dislocation and repair the proximal humeral fracture. If the fractures are not displaced (<1 cm of displacement), wearing a sling or a sling and swath may be all the treatment that is required. If significant displacement remains after closed reduction, ORIF will be necessary.8 Orthopedic consultation should be obtained in almost all cases.

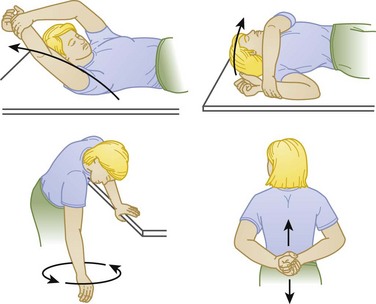

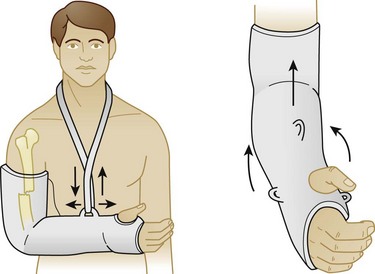

Successful treatment is most dependent on early mobility. Prolonged immobilization without range-of-motion exercises often results in adhesive capsulitis or a marked reduction in mobility of the glenohumeral joint. Patients should be encouraged to perform circumduction range-of-motion exercises after a few days of immobilization, especially elderly patients (Fig. 87.21).

Humeral Shaft Fractures

Most humeral shaft fractures can be treated conservatively. If the fracture fragments are minimally displaced, no reduction is necessary. If the fragments are widely separated, reduction may be carried out before splinting.27 If the fracture fragments are in reasonable apposition (within 1 to 2 inches) following the reduction, the most commonly used splinting technique is the coaptation or sugar-tong splint, whereby a 5-inch plaster or Orthoglass splint is applied over the shoulder, down the lateral side of the upper part of the arm, around the elbow, and up the medial side of the upper part of the arm near the axilla. The arm is then placed in a sling with the sling around the wrist so that the weight of the splint will bring the fracture fragments together (Fig. 87.22). If the fracture fragments are separated more than 2 inches after reduction or if a spiral fracture is present, the hanging cast technique may be used. A lightweight cast is applied 1 to 2 inches proximal to the fracture site up to the palmar crease of the hand. The elbow is flexed to 90 degrees and a loop is placed at the wrist either on the dorsal side to reduce lateral angulation or on the volar side to reduce medial angulation (Fig. 87.23). The hanging cast has the disadvantage of needing gravity for traction; therefore, patients must remain upright at all times, even during sleep. Many patients cannot tolerate this.

The most common and most feared complication of humeral shaft fractures is radial nerve injury. If nerve function is lost before reduction, most authorities treat it expectantly. Most of the time nerve function returns because the nerve has been either contused or stretched. After reduction, function of the radial nerve should again be tested.28 If radial nerve function is compromised but was normal before reduction, most authorities recommend ORIF because the probability is high that the radial nerve is entrapped within the fracture.29

Supracondylar Fractures

Type II fractures require reduction even though they are minimally displaced. Following reduction, a long arm splint is applied with the elbow flexed to 100 to 120 degrees. Flexion greater than 90 degrees places tension on the intact posterior periosteum to maintain the reduction. Because this degree of hyperextension may compromise neurovascular structures volar to the elbow, careful attention should be paid to ensure that this complication does not arise, especially in the first 2 to 3 days after the fracture.30,31 Orthopedic consultation should be obtained in all cases.

Type III injuries are problematic because they may increase the chance for a varus deformity and are more likely to cause injury to the neurovascular structures passing through the elbow. Rarely should an attempt be made to reduce these fractures in the ED. The only exception might be the unavailability of immediate orthopedic consultation for a patient who has an obviously occluded brachial artery. The vast majority of these patients should be taken to the operating room immediately and undergo either closed or open reduction.32 Orthopedic consultation is mandatory in all cases.

The most common complication is loss of the normal carrying angle, which results in a cubitus varus deformity. This complication has decreased in incidence as the practice of percutaneous pinning of the fracture has evolved. More serious complications of supracondylar fractures include brachial artery injury and injuries to the radial, median, and ulnar nerves. Most often these injuries are due to contusion or stretching of the nerves, and full recovery is the rule.30

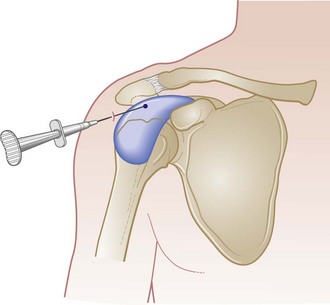

Rotator Cuff Tendinitis/subacromial Bursitis, Rotator Cuff Tears, and Impingement Syndromes

Treatment depends on the degree of disability (incomplete versus complete tear), the patient’s age, and the patient’s activity level. In patients with tendinitis or subacromial bursitis, an injection into the subacromial bursa usually results in relief of pain (Fig. 87.24). In young, active patients with significant rotator cuff tears, arthroscopic repair is indicated. In older patients with a sedentary lifestyle, repair should rarely be attempted because the outcome is often worse than that with conservative therapy. For evaluation, patients should be referred for consultation with an orthopedist who specializes in shoulder injuries.33

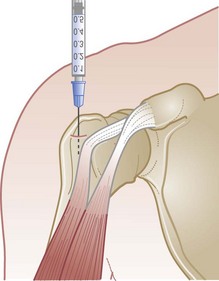

Tenosynovitis and Rupture of the Long Head of the Biceps Tendon

Conservative treatment consists of a sling and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). If after a week of immobilization the patient continues to have pain, the bicipital canal can be injected with a combined local anesthetic and steroid (Fig. 87.25). Range-of-motion exercises should be performed daily to prevent adhesive tenosynovitis.

Adhesive Capsulitis

The most important form of therapy should be directed at prevention of this problem. All patients with shoulder injuries or inflammation should be encouraged to perform circumduction range-of-motion exercises daily to prevent adhesive capsulitis. Conservative treatment consists of a gentle exercise program, NSAIDs, and corticosteroid injections.33 Such treaent results in significant improvement in many patients; however, many others require the adhesions to be broken up by putting the shoulder through full range of motion under general anesthesia.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Glenohumeral Dislocations

Most dislocations can be reduced with some type of conscious sedation in the ED. In some cases the relocation will be unsuccessful and the patient must be taken to the operating room for relocation. Following relocation, the patient may be discharged with a sling or a sling and swath. The sling should be kept on for 3 to 5 weeks, and the patient should perform circumduction range-of-motion exercises until the sling is removed. Complications include fracturing of the humerus during reduction and injury to the axillary nerve, which should be checked before and after reduction. Prereduction radiographs are recommended. However, routinely obtaining postreduction radiographs is controversial, especially if the patient is asymptomatic.34 The sling should be left on for approximately 4 weeks.

Baratz M, Micucci C, Sangimino M. Pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. Hand Clin. 2006;22:69–75.

Dodson CC, Cordasco FA. Anterior glenohumeral joint dislocations. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39:507–518.

Klein SM, Badman BL, Keating CJ, et al. Results of surgical treatment for unstable distal clavicular fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:1049–1055.

Lenza M, Belloti JC, Andriolo RB, et al. Conservative interventions for treating middle third clavicle fractures in adolescents and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2009. CD007121

Macdonald PB, Lapointe P. Acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39:535–545.

Malik S, Chiampas G, Leonard H. Emergent evaluation of injuries to the shoulder, clavicle and humerus. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:739–763.

1 Macdonald PB, Lapointe P. Acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39:535–545.

2 Garretson RB, Williams GR. Clinical evaluation of injuries to the acromial and sternoclavicular joints. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22:239–254.

3 Ernberg LA, Potter HG. Radiographic evaluation of the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22:255–275.

4 Bossart PJ, Joyce SM, Manaster BJ, et al. Lack of efficacy of “weighted radiographs” in diagnosing acute acromioclavicular separation. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:20–24.

5 Ada JR, Miller ME. Scapular fractures: analysis of 113 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;269:174–180.

6 Geusens E, Pans S, Verhulst D, et al. The modified axillary view of the shoulder: a painless alternative. Emerg Radiol. 2006;12:227–230.

7 Cicak N. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:324–332.

8 Neer 2nd, CS. Displaced proximal humerus fractures: part I. Classification and evaluation. 1970. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;442:77–82.

9 Park HB, Yokota A, Gill HS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the different degrees of subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1446–1455.

10 Nho SJ, Strauss EJ, Lenart BA, et al. Long head of the biceps tendinopathy: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:645–656.

11 Tamaoki MJ, Belloyi JC, Lenza M, et al. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating acromioclavicular dislocation of the shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 8, 2010. CD007429

12 Schlegel TF, Burks RT, Marcus RL, et al. A prospective evaluation of untreated acute grade III acromioclavicular separations. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:699–703.

13 Press J, Zuckerman JD, Gallagher M, et al. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations. Operative versus nonoperative management. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1997;56:77–83.

14 Bellotti LM, Gomes Dos Santos JB, Matsumoto MH, et al. Surgical interventions for treating acute fractures or non-union of the middle third of the clavicle. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2009. CD007428

15 Klein SM, Badman BL, Keating CJ, et al. Results of surgical treatment for unstable distal clavicular fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:1049–1055.

16 Pearson AM, Tosteson AN, Koval KJ, et al. Is surgery for displaced, midshaft clavicular fractures in adults cost effective? Results based on a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:426–433.

17 Deafenbaugh MK, Dugdale TW, Staeheli JW, et al. Nonoperative treatment of Neer type II distal clavicle fractures: a prospective study. Contemp Orthop. 1990;20:405–413.

18 Lenza M, Belloti JC, Andriolo RB, et al. Conservative interventions for treating middle third clavicle fractures in adolescents and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2009. CD007121

19 Kuhn JE. Treating the initial anterior shoulder dislocation—an evidence based medicine approach. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2006;13:192–198.

20 Cheok CY, Mohamad JA, Ahmad TS, et al. Pain relief for reduction of acute anterior shoulder dislocations: a prospective randomized study comparing intravenous sedation with intra-articular lidocaine. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25:5–10.

21 Baykal B, Senter S, Turkan H, et al. Scapular manipulation technique for reduction of traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation: experience at an academic emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:336–338.

22 Eachempati KK, Dua A, Malhotra R, et al. The external rotator method for reduction of acute anterior dislocation and fracture-dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2431–2434.

23 Westin CD, Gill EA, Noyes ME, et al. Anterior shoulder dislocation. A simple and rapid method for reduction. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:369–371.

24 Nho SJ, Dodson CC, Bardzik KF, et al. The two-step maneuver for closed reduction of inferior glenohumeral dislocation (luxatio erecta to anterior dislocation to reduction). J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:354–357.

25 Denard Jr, A., Richards JE, Obremskey WT, et al. Outcome of nonoperative vs operative treatment of humeral shaft fractures: a retrospective study of 213 patients. Orthopedics. 33(8), 2010 Aug 11. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100625-16

26 Ponzer ER, Tomkvist H, Adami J, et al. Primary radial nerve palsy in patients with acute humeral shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:408–414.

27 Elton SG. Management of radial nerve injury associated with humeral shaft fractures: an evidence based approach. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2008;24:569–573.

28 Babal JC, Mehlman CT, Klein G. Nerve injuries associated with pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30:253–263.

29 Robb JE. The pink, pulseless hand after supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1410–1412.

30 Ramachandran M, Skaggs DL, Crawford HA, et al. Delaying treatment of supracondylar fractures in children: has the pendulum swung too far? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1228–1233.

31 Codsi MJ. The painful shoulder. When to inject and when to refer. Clev Clin J Med. 2007;74:473–474. 477–8, 480–2 passim

32 Nho SJ, Strauss EJ, Lenart BA, et al. Long head of the biceps tendinopathy: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:645–656.

33 Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM. Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2003. CD004016

34 Hendey GW. Necessity of radiographs in the emergency department management of shoulder dislocations. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:108–113.