Chapter 627 Injuries to the Eye

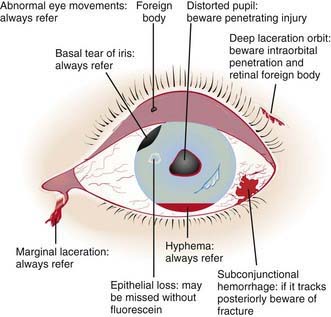

About 30% of all blindness in children results from trauma. Children and adolescents account for a disproportionate number of episodes of ocular trauma. Boys ages 11-15 yr are the most vulnerable; their injuries outnumber those in girls by a ratio of about 4 : 1. The majority of injuries are related to sports, toy darts, other projectiles, sticks, stones, fireworks, paint balls, and air-powered BB guns. The last causes particularly devastating ocular and orbital injuries. Much of the trauma is avoidable (Chapter 5.1). Any part of the orbit or globe may be affected (Fig. 627-1).

Figure 627-1 The injured eye.

(From Khaw PT, Shah P, Elkington AR: Injury to the eye, BMJ 328:36–38, 2004.)

Foreign Body involving the Ocular Surface

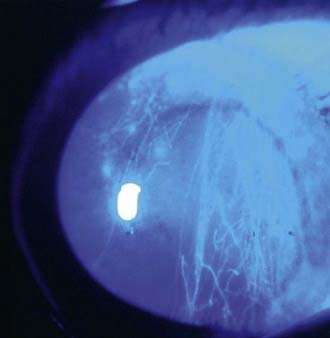

A foreign body usually produces acute discomfort, lacrimation, and inflammation. Most foreign bodies can be detected by examination in good light with the aid of magnification or a direct ophthalmoscope set on a high plus lens (+10 or +12). In many cases, slit-lamp examination is necessary, especially if the particle is deep or metallic. Some conjunctival foreign bodies tend to lodge under the upper eyelid, causing the sensation of corneal foreign body as they come into contact with the globe on eyelid movement; they can also produce vertically oriented linear corneal abrasions (Fig. 627-2). Finding these abrasions should lead to a suspicion of such a foreign body, and eversion of the lid may be necessary (Chapter 611). If a foreign body is suspected but not found, further examination is indicated. If the history suggests injury with a high-velocity particle, radiologic examination of the eye may be needed to explore the possibility of an intraocular foreign body.

Child Abuse

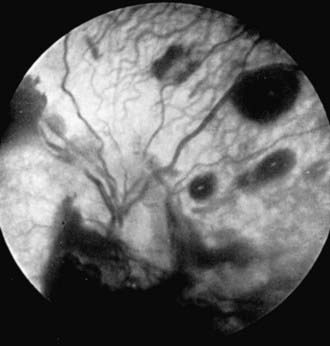

Child abuse (Chapter 37) is a major cause of injuries to the eye and orbital region. The possibility of nonaccidental trauma must be considered in any child with ecchymosis or laceration of the lids, hemorrhage in or about the eye, cataract or dislocated lens, retinal detachment, or fracture of the orbit. Inflicted childhood neurotrauma (shaken baby syndrome) occurs secondary to violent, nonaccidental, repetitive, unrestrained acceleration-deceleration head and neck movements, with or without blunt head trauma, in children typically <3 yr of age. Inflicted childhood neurotrauma accounts for approximately 10% of all cases of child abuse and carries a mortality rate of up to 25%. Detection of abuse is not only important in order to treat the pathology that is discovered but also to prevent further abuse or even death. The ocular manifestations are numerous and can have a prominent role in recognition of this syndrome. Retinal hemorrhage is the most common ophthalmic finding and occurs at all levels of the retina. The pattern of hemorrhage helps to distinguish this disorder from other causes of retinal hemorrhage or from accidental injuries (Fig. 627-3). Retinal hemorrhages can occur without associated intracranial pathology.

Sports-Related Ocular Injuries and Their Prevention

Although sports injuries occur in all age groups, far more children and adolescents participate in high-risk sports than do adults. The greater number of participating children, their athletic immaturity, and the increased likelihood of their using inadequate or improper eye protection account for their disproportionate share of sports-related eye injuries (Chapters 680 and 684).

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness, American Academy of Ophthalmology Committee on Eye Safety and Sports Ophthalmology. Protective eyewear for young athletes. Pediatrics. 1996;98:311-313.

Buys YM, Levin AV, Enzenauer RW, et al. Retinal findings after head trauma in infants and young children. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1718-1723.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Serious eye injuries associated with fireworks—United States, 1990–1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:449-452.

Crouch ERJr, Crouch ER. Management of traumatic hyphema: therapeutic options. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1999;36:238-250.

Egbert JE, May K, Kersten RC, et al. Pediatric orbital floor fracture: direct extraocular muscle involvement. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1875-1879.

Forbes BJ, Christian CW, Judkins AR, et al. Inflicted childhood neurotrauma (shaken baby syndrome): ophthalmic findings. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2004;41:80-88.

Goldenberg DT, Wu D, Capone AJr, et al. Nonaccidental trauma and peripheral retinal nonperfusion. Ophthalmology.. 2010;117:561-566.

Khaw PT, Shah P, Elkington AR. Injury to the eye. BMJ. 2004;328:36-38.

Kivlin JD, Simons KB, Lazoritz S, et al. Shaken baby syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1246-1254.

Lane K, Penne RB, Bilyk JR. Evaluation and management of pediatric orbital fractures in primary care setting. Orbit. 2007;26:183-191.

Michael JG, Hug D, Dowd MD. Management of corneal abrasion in children: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40:67-72.

Morad Y, Avni I, Benton SA, et al. Normal computerized tomography of brain in children with shaken baby syndrome. J AAPOS. 2004;8:445-450.

Prevent Blindness America. Most eye injuries in school-age children are sports-related. Prevent Blindness America urges public to make eye safety while playing sports a priority. Insight. 2009;34:26.

Smith GA, Knapp JF, Barnett TM, et al. The rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air: fireworks-related injuries to children. Pediatrics. 1996;98:1-9.