Chapter 319 Ingestions

319.1 Foreign Bodies in the Esophagus

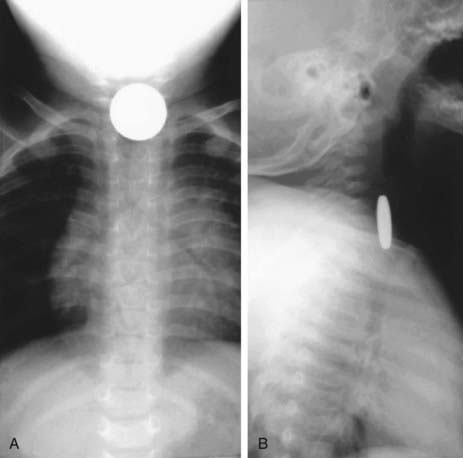

Evaluation of the child with a history of foreign body ingestion starts with plain anteroposterior (AP) radiographs of the neck, chest, and abdomen, along with lateral views of the neck and chest. The flat surface of a coin in the esophagus is seen on the AP view and the edge on the lateral view (Fig. 319-1). The reverse is true for coins lodged in the trachea; here, the edge is seen anteroposteriorly and the flat side is seen laterally. Disk batteries can look like coins (Fig. 319-2) and have a much higher risk of burns and necrosis (Fig. 319-3). Materials such as plastic, wood, glass, aluminum, and bones may be radiolucent; failure to visualize the object with plain films in a symptomatic patient warrants urgent endoscopy. Although barium contrast studies may be helpful in the occasional asymptomatic patient with negative plain films, their use is to be discouraged because of the potential of aspiration as well as making subsequent visualization and object removal more difficult.

Figure 319-2 Disk battery impacted in esophagus. Note the double rim.

(From Wyllie R, Hyams JS, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.)

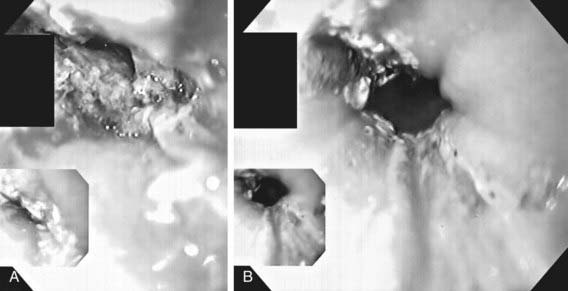

Treatment of esophageal foreign bodies usually merits endoscopic visualization of the object and underlying mucosa and removal of the object; therapeutic endoscopy is most conservatively done with an endotracheal tube protecting the airway. Sharp objects in the esophagus, disk button batteries, or foreign bodies associated with respiratory symptoms mandate urgent removal. Button batteries, in particular, must be expediently removed because they can induce mucosal injury in as little as 1 hr of contact time and involve all esophageal layers within 4 hr (see Fig. 319-3). Asymptomatic blunt objects and coins lodged in the esophagus can be observed for up to 24 hr in anticipation of passage into the stomach. If there are no problems in handling secretions, meat impactions can be observed for up to 12 hr. In patients without prior esophageal surgeries, glucagon (0.05 mg/kg IV) can sometimes be useful in facilitating passage of distal esophageal food boluses by decreasing the LES pressure. The use of meat tenderizers or gas-forming agents can lead to perforation and are not recommended. An alternative technique for removing esophageal coins impacted for <24 hr, performed most safely by experienced radiology personnel, consists of passage of a Foley catheter beyond the coin at fluoroscopy, inflating the balloon, and then pulling the catheter and coin back simultaneously with the patient in a prone oblique position. Concerns about the lack of direct mucosal visualization and, when tracheal intubation is not used, the lack of airway protection prompt caution in the use of this technique. Bougienage of esophageal coins toward the stomach in selected uncomplicated pediatric cases has been suggested to be an effective, safe, and economical modality where endoscopy might not be routinely available.

319.2 Caustic Ingestions

Ingestion of caustic substances can result in esophagitis, necrosis, perforation, and stricture formation (Chapter 58). Most cases (70%) are accidental ingestions of liquid alkali substances that produce severe, deep liquefaction necrosis; drain decloggers are most common, and because they are tasteless, more is ingested (Table 319-1). Acidic agents (20% of cases) are bitter, so less may be consumed; they produce coagulation necrosis and a somewhat protective thick eschar. They can produce severe gastritis, and volatile acids can result in respiratory symptoms. Children <5 yr of age account for half of the cases of caustic ingestions, and boys are far more commonly involved than girls.

| CATEGORY | MOST DAMAGING AGENTS | OTHER AGENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaline drain cleaners, milking machine pipe cleaners | Sodium or potassium hydroxide |

Source: National Library of Medicine: Health and safety information on household products (website). http://householdproducts.nlm.nih.gov/. Accessed April 28, 2010. From Wyllie R, Hyams JS, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.

Dilution by water or milk is recommended as acute treatment, but neutralization, induced emesis, and gastric lavage are contraindicated. Treatment depends on the severity and extent of damage (Table 319-2). Stricture risk is increased by circumferential ulcerations, white plaques, and sloughing of the mucosa. Strictures can require treatment with dilation, and in some severe cases, surgical resection and colon or small bowel interposition are needed. Silicone stents (self-expanding) placed endoscopically after a dilatation procedure can be an alternative and conservative approach to the management of strictures. Rare late cases of superimposed esophageal carcinoma are reported. The role of corticosteroids is controversial; they are not recommended in 1st-degree burns, but they can reduce the risk of strictures in more-advanced caustic esophagitis. Some centers also use antibiotics in the initial treatment of caustic esophagitis on the premise that reducing superinfection in the necrotic tissue bed will in turn lower the risk of stricture formation. However, multiple studies examining the role of antibiotics in caustic esophagitis have not reported a clinically significant benefit even in those with grade 2 or greater severity of esophagitis.

Table 319-2 SEVERITY OF ESOPHAGEAL INJURY FOLLOWING CAUSTIC INGESTION AS GRADED BY ENDOSCOPIC APPEARANCE OF THE ESOPHAGUS

| SEVERITY | ENDOSCOPIC APPEARANCE OF ESOPHAGEAL MUCOSA |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | Normal mucosa |

| Grade 1 | Erythema |

| Grade 2 | Erythema, sloughing, ulceration, and exudates (not circumferential) |

| Grade 3 | Deep mucosal sloughing and ulceration (circumferential) |

| Grade 4 | Eschar, full thickness injury and perforation |

Betalli P, Falchetti D, Giuliani S, et al. Caustic ingestion in children: is endoscopy always indicated? The results of an Italian multicenter observational study. Gastroinest Endosc. 2008;68:434-439.

Contini S, Garatti M, Swarray-Deen A, et al. Corrosive esophageal strictures in children: outcomes after timely or delayed dilatation. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:263-268.

Riffat F, Cheng A. Pediatric caustic ingestions: 50 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:89-94.