Chapter 328 Inflammatory Bowel Disease

It is usually possible to distinguish between ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease by the clinical presentation and radiologic, endoscopic, and histopathologic findings (Table 328-1). It is not possible to make a definitive diagnosis in ∼10% of patients with chronic colitis; this disorder is called indeterminate colitis. Occasionally, a child initially believed to have ulcerative colitis on the basis of clinical findings is subsequently found to have Crohn colitis. This is particularly true for the youngest patients, because Crohn disease in this patient population can more often manifest as exclusively colonic inflammation, mimicking ulcerative colitis. The medical treatments of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis overlap.

Table 328-1 COMPARISON OF CROHN DISEASE AND ULCERATIVE COLITIS

| FEATURE | CROHN DISEASE | ULCERATIVE COLITIS |

|---|---|---|

| Rectal bleeding | Sometimes | Common |

| Diarrhea, mucus, pus | Variable | Common |

| Abdominal pain | Common | Variable |

| Abdominal mass | Common | Not present |

| Growth failure | Common | Variable |

| Perianal disease | Common | Rare |

| Rectal involvement | Occasional | Universal |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Rare | Present |

| Erythema nodosum | Common | Less common |

| Mouth ulceration | Common | Rare |

| Thrombosis | Less common | Present |

| Colonic disease | 50-75% | 100% |

| Ileal disease | Common | None except backwash ileitis |

| Stomach-esophageal disease | More common | Chronic gastritis can be seen |

| Strictures | Common | Rare |

| Fissures | Common | Rare |

| Fistulas | Common | Rare |

| Toxic megacolon | None | Present |

| Sclerosing cholangitis | Less common | Present |

| Risk for cancer | Increased | Greatly increased |

| Discontinuous (skip) lesions | Common | Not present |

| Transmural involvement | Common | Unusual |

| Crypt abscesses | Less common | Common |

| Granulomas | Common | None |

| Linear ulcerations | Uncommon | Common |

Extraintestinal manifestations occur slightly more commonly with Crohn disease than with ulcerative colitis (Table 328-2). Growth retardation is seen in 15-40% of children with Crohn disease at diagnosis. Of the extraintestinal manifestations that occur with IBD, joint, skin, eye, mouth, and hepatobiliary involvement tend to be associated with colitis, whether ulcerative or Crohn. The presence of some manifestations, such as peripheral arthritis, erythema nodosum, and anemia, correlates with activity of the bowel disease. Activity of pyoderma gangrenosum correlates less well with activity of the bowel disease, whereas sclerosing cholangitis, ankylosing spondylitis, and sacroiliitis do not correlate with intestinal disease. Arthritis occurs in 3 patterns: migratory peripheral arthritis involving primarily large joints, ankylosing spondylitis, and sacroiliitis. The peripheral arthritis of IBD tends to be nondestructive. Ankylosing spondylitis begins in the 3rd decade and occurs most commonly in patients with ulcerative colitis who have the human leukocyte antigen B27 phenotype. Symptoms include low back pain and morning stiffness; back, hips, shoulders, and sacroiliac joints are typically affected. Isolated sacroiliitis is usually asymptomatic but is common when a careful search is performed. Among the skin manifestations, erythema nodosum is most common. Patients with erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosum have a high likelihood of having arthritis as well. Glomerulonephritis, uveitis, and a hypercoagulable state are other rare manifestations that occur in childhood. Cerebral thromboembolic disease has been described in children with IBD.

Table 328-2 EXTRAINTESTINAL COMPLICATIONS OF INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

MUSCULOSKELETAL

SKIN AND MUCOUS MEMBRANES

DERMATOLOGIC

OCULAR

BRONCHOPULMONARY

CARDIAC

MALNUTRITION

HEMATOLOGIC

RENAL AND GENITOURINARY

PANCREATITIS

HEPATOBILIARY

ENDOCRINE AND METABOLIC

NEUROLOGIC

G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Modified from Kugathasan S: Diarrhea. In Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS, editors: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Saunders, p 285.

328.1 Chronic Ulcerative Colitis

Differential Diagnosis

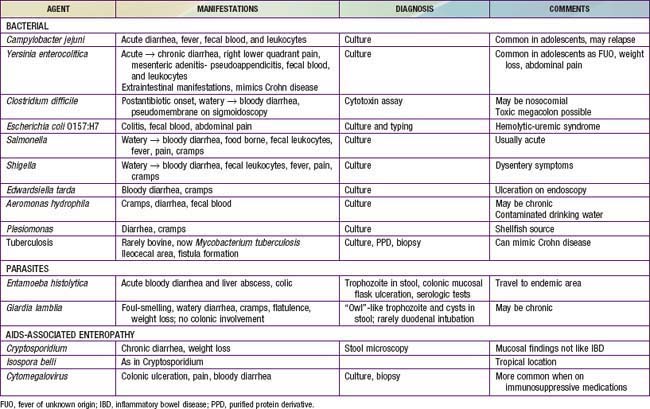

The major conditions to exclude are infectious colitis, allergic colitis, and Crohn colitis. Every child with a new diagnosis of ulcerative colitis should have stool cultured for enteric pathogens, stool evaluation for ova and parasites, and perhaps serologic studies for amebae (Table 328-3). In the setting of antibiotic use, pseudomembranous colitis secondary to Clostridium difficile should be considered. Cytomegalovirus infection can mimic ulcerative colitis or be associated with an exacerbation of existing disease. The most difficult distinction is from Crohn disease because the colitis of Crohn disease can initially appear identical to that of ulcerative colitis, particularly in younger children. The gross appearance of the colitis or development of small bowel disease eventually leads to the correct diagnosis; this can occur years after the initial presentation.

At the onset, the colitis of hemolytic-uremic syndrome may be identical to that of early ulcerative colitis. Ultimately, signs of microangiopathic hemolysis (the presence of schistocytes on blood smear), thrombocytopenia, and subsequent renal failure should confirm the diagnosis of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Although Henoch-Schönlein purpura can manifest as abdominal pain and bloody stools, it is not usually associated with colitis. Behçet disease can be distinguished by its typical features (Chapter 155). Other considerations are radiation proctitis, viral colitis in immunocompromised patients, and ischemic colitis (Table 328-4). In infancy, dietary protein intolerance can be confused with ulcerative colitis, although the former is a transient problem that resolves on removal of the offending protein, and ulcerative colitis is extremely rare in this age group. Hirschsprung disease can produce an enterocolitis before or within months after surgical correction; this is unlikely to be confused with ulcerative colitis.

Table 328-4 CHRONIC INFLAMMATORY-LIKE INTESTINAL DISORDERS

INFECTION (SEE TABLE 328-3)

AIDS-ASSOCIATED

IMMUNE-INFLAMMATORY

VASCULAR-ISCHEMIC DISORDERS

OTHER

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis or ulcerative proctitis requires a typical presentation in the absence of an identifiable specific cause (see Tables 328-3 and 328-4) and typical endoscopic and histologic findings (see Table 328-1). One should be hesitant to make a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis in a child who has experienced symptoms for <2-3 wk until infection has been excluded. When the diagnosis is suspected in a child with subacute symptoms, the physician should make a firm diagnosis only when there is evidence of chronicity on colonic biopsy. Laboratory studies can demonstrate evidence of anemia (either iron deficiency or the anemia of chronic disease) or hypoalbuminemia. Although the sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are often elevated, they may be normal even with fulminant colitis. An elevated white blood cell count is usually seen only with more-severe colitis. Fecal calprotectin levels are usually elevated. Barium enema is suggestive but not diagnostic of acute (Fig. 328-1) or chronic burned-out disease (Fig. 328-2).

AGA Institute Medical Position Panel. AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:738-745.

Anderson CA, Boucher G, Lees CW, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 29 additional ulcerative colitis risk loci, increasing the number of confirmed associations to 47. Nat Genet. 2011;43:246-252.

Baumgart DC, Carding SR. Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet. 2007;369:1627-1640.

Beattie RM, Croft NM, Fell JM, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:426-432.

Brest P, Lapaquette P, Souidi M, et al. A synonymous variant in IRGM alters a binding site for miR-196 and causes deregulation of IRGM-dependent xerophagy in Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43(3):242-245.

Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(15):1383-1394.

Dolgin SE, Shlasko E, Gorfine S, et al. Restorative proctocolectomy in children with ulcerative colitis utilizing rectal mucosectomy with or without diverting ileostomy. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:837-839.

Dubois PC, van Heel DA. New susceptibility genes for ulcerative colitis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:686-688.

Franke A, Balschun T, Karlsen TH, et al. Sequence variants in IL10, ARPC2 and multiple other loci contribute to ulcerative colitis susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1319-1323.

Gionchetti P, Rizello F, Helwig U, et al. Prophylaxis of pouchitis onset with probiotic therapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1202-1209.

Heyman M, Kirschner BS, Gold BD, et al. Children with early onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): analysis of a pediatric IBD consortium registry. J Pediatr. 2004;146:35-40.

Ho GT, Mowat C, Goddard CJ, et al. Predicting the outcome of severe ulcerative colitis: development of a novel risk score to aid early selection of patients for second-line medical therapy or surgery. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1079-1087.

IBD in EPIC Study Investigators. Linoleic acid, a dietary n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and the aetiology of ulcerative colitis: a nested case control study within a European prospective cohort study. Gut. 2009;58:1606-1611.

Jose FA, Heyman MB. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:124-133.

Kruis W, Fric P, Pokrotnieks J, et al. Maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis with the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is as effective as with standard mesalazine. Gut. 2004;53:1617-1623.

Kugathasan S, Judd RH, Hoffmann RG, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in Wisconsin: a statewide population-based study. J Pediatr. 2003;143:525-531.

Leggieri N, Marques-Vidal P, Cerwenka H, et al. Migrated foreign body liver abscess. Medicine. 2010;89(2):85-95.

Malaty HM, Fan X, Opekun AR, et al. Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among children: a 12-year study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50(1):27-31.

Mamula P, Markowitz JE, Baldassano RN. Inflammatory bowel disease in early childhood and adolescence: special considerations. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:967-995.

Mamula P, Markowitz JE, Cohen LJ, et al. Infliximab in pediatric ulcerative colitis: two-year follow-up. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:298-301.

Medical Letter. Encapsulated mesalamine granules (Apriso) for ulcerative colitis. Med Lett. 2009;51:38-40.

Momozawa Y, Mni M, Nakamura K, et al. Resequencing of positional candidates identifies low frequency IL23R coding variants protecting against inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43(1):43-47.

Quail MA, Russell RK, Van Limbergen JE, et al. Fecal calprotectin complements routine laboratory investigations in diagnosing childhood inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:756-759.

Romano C, Famiani A, Gallizzi R, et al. Indeterminate colitis: a distinctive clinical pattern of inflammatory bowel disease in children. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1278-e1281.

Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462-2476.

Sanderson JD, Parkes GC. Timing of surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ. 2007;335:1006-1007.

Schwiertz A, Jacobi M, Frick JS, et al. Microbiota in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr. 2010;157:240-244.

Timmer A, Behrens R, Buderus S, et al. Childhood onset inflammatory bowel disease: predictors of delayed diagnosis from the CEDATA German-language pediatric inflammatory bowel disease registry. J Pediatr. 2011;158:467-473.

Timmer A, Obermeier F. Reduced risk of ulcerative colitis after appendectomy. BMJ. 2009;338:781-782.

Turner D, Walsh CM, Benchimol EI, et al. Severe paediatric ulcerative colitis: incidence, outcomes, and optimal timing for second-line therapy. Gut. 2008;57:331-338.

Turner D, Walsh CM, Steinhart H, et al. Response to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:103-110.

UK IBD Genetics Consortium and the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1330-1334.

328.2 Crohn Disease (Regional Enteritis, Regional Ileitis, Granulomatous Colitis)

Crohn disease, an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory disorder of the bowel, involves any region of the alimentary tract from the mouth to the anus. Although there are many similarities between ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, there are also major differences in the clinical course and distribution of the disease in the GI tract (see Table 328-1). The inflammatory process tends to be eccentric and segmental, often with skip areas (normal regions of bowel between inflamed areas). Although inflammation in ulcerative colitis is limited to the mucosa (except in toxic megacolon), GI involvement in Crohn disease is often transmural.

Clinical Manifestations

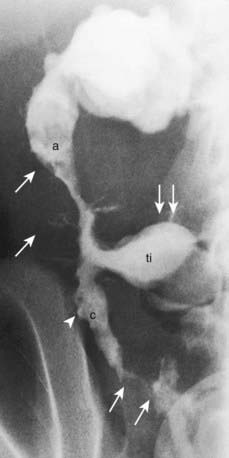

Systemic signs and symptoms are more common in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis. Fever, malaise, and easy fatigability are common. Growth failure with delayed bone maturation and delayed sexual development can precede other symptoms by 1 or 2 yr and is at least twice as likely to occur with Crohn disease as with ulcerative colitis. Children can present with growth failure as the only manifestation of Crohn disease. Causes of growth failure include inadequate caloric intake, suboptimal absorption or excessive loss of nutrients, the effects of chronic inflammation on bone metabolism and appetite, and the use of corticosteroids during treatment. Primary or secondary amenorrhea and pubertal delay are common. In contrast to ulcerative colitis, perianal disease is common (tags, fistula, abscess). Gastric or duodenal involvement may be associated with recurrent vomiting and epigastric pain. Partial small bowel obstruction, usually secondary to narrowing of the bowel lumen from inflammation or stricture, can cause symptoms of cramping abdominal pain (especially with meals), borborygmus, and intermittent abdominal distention (Fig. 328-3). Stricture should be suspected if the child notes relief of symptoms in association with a sudden sensation of gurgling of intestinal contents through a localized region of the abdomen.

Penetrating disease is demonstrated by fistula formation. Enteroenteric or enterocolonic fistulas (between segments of bowel) are often asymptomatic but can contribute to malabsorption if they have high output or result in bacterial overgrowth (Fig. 328-4). Enterovesical fistulas (between bowel and urinary bladder) originate from ileum or sigmoid colon and appear as signs of urinary infection, pneumaturia, or fecaluria. Enterovaginal fistulas originate from the rectum, cause feculent vaginal drainage, and are difficult to manage. Enterocutaneous fistulas (between bowel and abdominal skin) often are caused by prior surgical anastomoses with leakage. Intra-abdominal abscess may be associated with fever and pain but might have relatively few symptoms. Hepatic or splenic abscess can occur with or without a local fistula. Anorectal abscesses often originate immediately above the anus at the crypts of Morgagni. The patterns of perianal fistulas are complex because of the different tissue planes. Perianal abscess is usually painful, but perianal fistulas tend to produce fewer symptoms than anticipated. Purulent drainage is commonly associated with perianal fistulas. Psoas abscess secondary to intestinal fistula can present as hip pain, decreased hip extension (psoas sign), and fever.

Extraintestinal manifestations occur more commonly with Crohn disease than with ulcerative colitis; those that are especially associated with Crohn disease include oral aphthous ulcers, peripheral arthritis, erythema nodosum, digital clubbing, episcleritis, renal stones (uric acid, oxalate), and gallstones. Any of the extraintestinal disorders described in the section on IBD can occur with Crohn disease (see Table 328-2). The peripheral arthritis is nondeforming. The occurrence of extraintestinal manifestations usually correlates with the presence of colitis.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common diagnoses to be distinguished from Crohn disease are the infectious enteropathies (in the case of Crohn disease: acute terminal ileitis, infectious colitis, enteric parasites, and periappendiceal abscess) (see Tables 328-3, 328-4, and 328-5). Yersinia can cause many of the radiologic and endoscopic findings in the distal small bowel that are seen in Crohn disease. The symptoms of bacterial dysentery are more likely to be mistaken for ulcerative colitis than for Crohn disease. Celiac disease and Giardia infection have been noted to produce a Crohn-like presentation including diarrhea, weight loss, and protein-losing enteropathy. GI tuberculosis is rare but can mimic Crohn disease. Foreign-body perforation of the bowel (toothpick) can mimic a localized region with Crohn disease. Small bowel lymphoma can mimic Crohn disease but tends to be associated with nodular filling defects of the bowel without ulceration or narrowing of the lumen. Bowel lymphoma is much less common in children than is Crohn disease. Recurrent functional abdominal pain can mimic the pain of small bowel Crohn disease. Lymphoid nodular hyperplasia of the terminal ileum (a normal finding) may be mistaken for Crohn ileitis. Right lower quadrant pain or mass with fever can be the result of periappendiceal abscess. This entity is occasionally associated with diarrhea as well.

Table 328-5 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF PRESENTING SYMPTOMS OF CROHN DISEASE

| PRIMARY PRESENTING SYMPTOM | DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

| Right lower quadrant abdominal pain, with or without mass | Appendicitis, infection (e.g., Campylobacter, Yersinia spp.), lymphoma, intussusception, mesenteric adenitis, Meckel diverticulum, ovarian cyst |

| Chronic periumbilical or epigastric abdominal pain | Irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, lactose intolerance, peptic disease |

| Rectal bleeding, no diarrhea | Fissure, polyp, Meckel diverticulum, rectal ulcer syndrome |

| Bloody diarrhea | Infection, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, ischemic bowel, radiation colitis |

| Watery diarrhea | Irritable bowel syndrome, lactose intolerance, giardiasis, Cryptosporidium infection, sorbitol, laxatives |

| Perirectal disease | Fissure, hemorrhoid (rare), streptococcal infection, condyloma (rare) |

| Growth delay | Endocrinopathy |

| Anorexia, weight loss | Anorexia nervosa |

| Arthritis | Collagen vascular disease, infection |

| Liver abnormalities | Chronic hepatitis |

From Kugathasan S: Diarrhea. In Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS, editors: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Saunders, p 287.

Diagnosis

Radiologic studies are necessary to assess the entire small bowel and investigate for evidence of structuring or penetrating disease. A variety of findings may be apparent on radiologic studies. Plain films of the abdomen may be normal or might demonstrate findings of partial small bowel obstruction or thumbprinting of the colon wall. An upper GI contrast study with small bowel follow-through might show aphthous ulceration and thickened, nodular folds as well as narrowing or stricturing of the lumen. Linear ulcers can give a cobblestone appearance to the mucosal surface. Bowel loops are often separated as a result of thickening of bowel wall and mesentery. Other manifestations on radiographic studies that suggest more-severe Crohn disease are fistulas between bowel (enteroenteric or enterocolonic), sinus tracts, and strictures (see Figs. 328-3 and 328-4).

Prognosis

The region of bowel involved often increases with time, although rapid progression typically occurs early and is subsequently slow. Complications of the inflammatory process tend to increase with time and include bowel strictures, fistulas, perianal disease, and intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal abscess. A majority of patients with Crohn disease eventually require surgery for one of its many complications; the rate of reoperation is high. The time between the onset of symptoms and the need for surgery appears to be shorter in children than in adults. Surgery is unlikely to be curative and should be avoided except for the specific indications noted previously. Repeated small bowel resection, which may be unavoidable, can lead to malabsorption secondary to short bowel syndrome (Chapter 330.7). Resection of terminal ileum can result in bile acid malabsorption with diarrhea and vitamin B12 malabsorption. The risk of colon cancer in patients with long-standing Crohn colitis approaches that associated with ulcerative colitis, and screening colonoscopy after 10 years of colonic disease is indicated.

Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2066-2076.

Ardizzone S, Maconi G, Sampietro GM, et al. Azathioprine and mesalamine for prevention of relapse after conservative surgery for Crohn disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:730-740.

Akobeng AK. Crohn’s disease: current treatment options. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:787-792.

Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DI, et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:955-962.

Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641-1657.

Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1617-1624.

Borelli O, Cordischi L, Cirulli M, et al. Polymeric diet alone versus corticosteroids in the treatment of active pediatric Crohn’s disease: a randomized controlled open-label trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:744-753.

Canani RB, de Horatio LT, Terrin G, et al. Combined use of noninvasive tests is useful in the initial diagnostic approach to a child with suspected inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastro Nutr. 2006;42:9-15.

Cooney R, Baker J, Brain O, et al. NOD2 stimulation induces autophagy in dendritic cells influencing bacterial handling and antigen presentation. Nat Med. 2010;16:90-97.

Coulombe F, Behr MA. Crohn’s disease as an immune deficiency? Lancet. 2009;374:769-770.

D’Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomized trial. Lancet. 2008;371:660-667.

Escher JC. Budesonide vs. prednisolone for the treatment of of active Crohn’s disease in children: a randomized, double-blind, controlled, multicentre trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:47-54.

Farhi D, Cosnes J, Zizi N, et al. Significance of erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel diseases. Medicine. 2008;87:281-293.

Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Boztug K, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2033-2044.

Grainge MJ, West J, Card TR. Venous thromboembolism during active disease and remission in inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:657-662.

Gupta N, Bostrom AG, Kirschner BS, et al. Gender differences in presentation and course of disease in pediatric patients with Crohn disease. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1418-e1425.

Hanauer SB, Korelitz BI, Rutgeerts P, et al. Postoperative maintenance of Crohn’s disease remission with 6-mercaptopurine, mesalamine, or placebo: a 2 year trial. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:723-729.

Heyman MB, Garnett EA, Wojcicki J, et al. Growth hormone treatment for growth failure in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr. 2008;153:651-658.

Hyams J, Crandall W, Kugathasan S, et al. Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:863-873.

Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence of geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1424-1429.

Kugathasan S, Judd RH, Hoffmann RG, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in Wisconsin: a statewide population-based study. J Pediatrics. 2003;143:525-531.

McCarroll SA, Huett A, Kuballa P, et al. Deletion polymorphism upstream of IRGM associated with altered IRGM expression and Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1107-1112.

The Medical Letter. Certolizumab (Cimzia) for Crohn’s disease. Med Lett. 2008;50:81-82.

The Medical Letter. Natalizumab (Tysabri) for Crohn’s disease. Med Lett. 2008;50:34-36.

Otley A, Steinhart AH: Budesonide for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4)CD000296, 2005.

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Desreumaux P, Sandborn WJ, et al. Crohn’s disease: beyond antagonists of tumour necrosis factor. Lancet. 2008;372:67-81.

Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Muñoz S, et al. Autoimmune diseases induced by TNF-targeted therapies. Medicine. 2007;86:242-251.

Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Stoinov S, et al. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:228-238.

Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, et al. Adalimumab induction therapy for Crohn disease previously treated with infliximab. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:829-838.

Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885.

Schreiber S, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Lawrence IC, et al. Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:239-250.

Sentongo TA, Semeao EJ, Piccoli DA, et al. Growth, body composition, and nutritional status in children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;31:33-40.

Sinha R, Nwokolo C, Murphy PD. Magnetic resonance imaging in Crohn’s disease. BMJ. 2008;336:273-276.

Turner D, Grossman AB, Rosh J, et al. Methotrexate following unsuccessful thiopurine therapy in pediatric Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2804-2812.

Van Limbergen JV, Russell RK, Drummond HE, et al. Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1114-1122.

von Roon AC, Karamountzos L, Purkayastha S, et al. Diagnostic precision of fecal calprotectin for inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal malignancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:803-813.