36 Inflammatory Bowel Disease

• Acute exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease are characterized by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

• Life-threatening complications include bowel obstruction, hemorrhagic shock, toxic megacolon, malabsorption, abscess formation, and sepsis.

• Treatment with analgesics, intravenous hydration, antiemetics, and electrolyte replacement should occur in parallel with appropriate diagnostic imaging and laboratory studies.

• Antibiotics, steroids, and immunosuppressant therapies can be used in conjunction with specialty consultation.

• Hypersensitivity reactions may result from long-term immunomodulator and antiinflammatory therapies.

• Patients receiving immunosuppressant therapy have increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections.

Perspective

Approximately 1 million people in the United States suffer from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The two major forms of IBD are Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis (UC). The incidence of both disease processes is similar, although Crohn disease appears to be increasing.1 Each disease may relapse and remit, with exacerbations that often require emergency care and hospitalization.

IBD has a familial predilection, with an absolute risk of 7% among first-degree relatives.2,3 Up to a fifth of patients with IBD have an affected first-degree family member. Ashkenazi Jewish populations continue to have the highest documented incidence per capita of any group in the world. Hispanic and African American populations have a lower incidence of IBD than the Caucasian population does.4

The age at onset of IBD is bimodal. The greatest numbers of new cases are diagnosed in patients 15 to 35 years of age. Classically, a second peak is observed during the sixth decade of life.5 Advances in diagnostic testing have probably contributed to an overall rise in the number of new cases of IBD, as well as to the identification of the disease in younger patients.

Pathophysiology

Crohn Disease

Epidemiology

The cold chain hypothesis suggests that the rise in incidence of Crohn disease has been associated with the development of home refrigeration techniques. Bacteria that thrive in refrigerated foods, such as Yersinia and Listeria, are thought to play a role in stimulation of the immune and inflammatory responses that ultimately lead to Crohn disease.6 Exacerbations of Crohn disease may be worsened during periods of higher physiologic or mental stress.7 Other environmental factors such as cigarette smoking, use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), increased refined sugar intake, increased dietary fat, and decreased fiber intake have been linked to the development of Crohn disease.8–11

Genetic mutations and chromosomal variants have also been linked to the development of Crohn disease. Specific alterations in the NOD2 gene are associated with a 20-fold increase in the likelihood of Crohn disease with ileal predilection.12–15 Patients with Crohn disease may also be HLA-B27 positive.

Clinical Presentation

Crohn disease is associated with an increased risk for demyelinating diseases, as well as a higher incidence of inflammatory processes such as asthma, arthritis, bronchitis, psoriasis, and pericarditis.16,17 Approximately 20% of patients with Crohn disease experience one or more of the following extraintestinal manifestations of disease during their lifetimes: ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis, episcleritis, hepatitis, cholelithiasis, pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, cholangiocarcinoma, nephrolithiasis, and erythema nodosum (Fig. 36.1; Box 36.1).

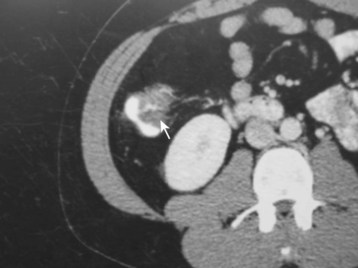

Fig. 36.1 Computed tomography scan showing terminal ileitis (arrow) in a patient with Crohn disease.

Epidemiology

The yearly incidence of UC is relatively constant—in the United States it is 8 per 100,000 people, with a disease prevalence of 246 cases per 100,000 people.18,19 The etiology of this disease is unknown, although certain risk factors have been identified. UC is most commonly found in North American and northern European Caucasian populations. In addition, similar to Crohn disease, development of UC has been linked to the use of NSAIDs, increased refined sugar intake, increased dietary fat, and decreased fiber intake.9–11 However, cigarette smoking appears to lessen the risk for development of UC.20

Clinical Presentation

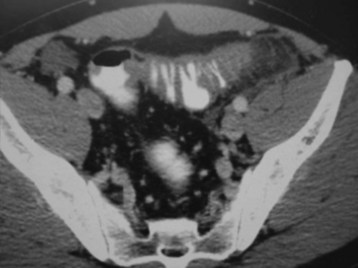

Patients with UC may have extraintestinal complications such as concurrent arthritis, uveitis, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and progressive liver disease (Fig. 36.2; Table 36.1).

| FINDING | CROHN DISEASE | ULCERATIVE COLITIS |

|---|---|---|

| Location | ||

| Colonic | Common | Common |

| Rectal | Common | Common |

| Extracolonic | Common | Never |

| Ileal | Common | Never |

| Signs and Symptoms | ||

| Fever | Common | Common |

| Diarrhea | Common | Common |

| Vomiting | Variable | Occasional |

| Abdominal pain | Common | Variable |

| Hematochezia | Variable | Common |

| Weight loss | Common | Common |

| Perianal disease | Common | Never |

| Pathologic Findings | ||

| Continuity | Discontinuous | Continuous |

| Inflammation | Transmural | Mucosal |

| Oral ulcers | Variable | Never |

| Fissures | Common | Never |

| Fistulas | Variable | Rare |

| Cobblestoning | Common | Never |

| Strictures | Common | Rare |

| Laboratory Findings | ||

| Perinuclease-staining antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA) positivity | Uncommon | Common |

| Anti–Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA) positivity | Common | Uncommon |

Diagnostic Testing

Imaging Modalities

Most cases of IBD diagnosed in the emergency department (ED) are found via computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen in patients with severe, unexplained abdominal pain. A presumptive diagnosis of IBD can be based on typical CT findings coupled with the appropriate signs and symptoms. CT enterography has been shown to have 100% sensitivity and 95% specificity for detection of small bowel lesions associated with Crohn disease.21 CT enterography is superior to standard CT of the abdomen and pelvis in patients with a high pretest probability of Crohn disease (i.e., first-degree family members of patients with IBD). Confirmation of the diagnosis is made by histologic examination of tissue biopsy specimens obtained via inpatient endoscopy or surgery.

Treatment

General Management

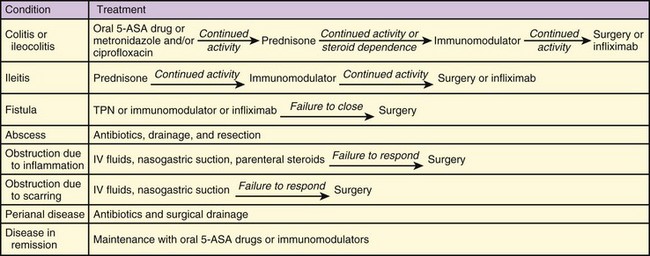

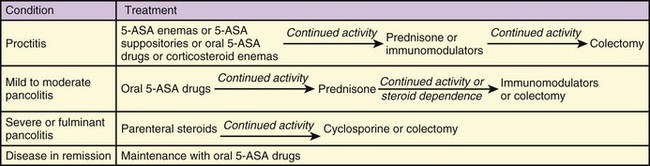

Immunomodulator, antiinflammatory, and antibiotic agents should be given in consultation with the patient’s gastroenterologist. Because these medications often require long-term administration and dose adjustments, complex drug regimens are typical. Treatment algorithms for Crohn disease and UC are summarized in Figures 36.3 and 36.4.

Common Medications

Oral steroids improve mild to moderate IBD symptoms within days to weeks and are used in patients who do not improve with 5-ASA agents. Prednisone, 40 mg/day, is an acceptable starting dose; equivalent parenteral administration should be reserved for severe disease or for patients who cannot tolerate oral medications. Long-term corticosteroid therapy at a low maintenance dose is often required. Patients with small bowel obstruction secondary to terminal ileitis may have a response to early treatment with steroids, thereby reducing the need for surgical intervention (Fig. 36.5).

Antibiotics may be needed to treat patients with Crohn disease. Antibiotics are indicated for active Crohn disease and pouchitis; promising results have been shown for fistulizing Crohn disease.22–25 The antibiotics most commonly used are a combination of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. The utility of these agents for UC has not been proved.

1 Loftus EV, Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 126, 2004. 1504-1501

2 Tysk C, Lindberg E, Jarnerot G, et al. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in an unselected population of monozygotic and dizygotic twins: a study of heritability and the influence of smoking. Gut. 1988;29:990–996.

3 Orholm M, Munkholm P, Langhoz E, et al. Familial occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:84–88.

4 Calkins BM, Lilienfeld AM, Garland CF, et al. Trends in incidence rates of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:913–930.

5 Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, et al. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: a large, population-based study in Sweden. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:350–358.

6 Hugot JP, Alberti C, Berrebi D, et al. Crohn’s disease: the cold chain hypothesis. Lancet. 2003;362:2012–2015.

7 Vidal A, Gómez-Gil E, Sans M, et al. Life events and inflammatory bowel disease relapse: a prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1–7.

8 Silverstein MD, Lashner BA, Hanauer SB, et al. Cigarette smoking in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:31–33.

9 Tanner AR, Raghunath AS. Colonic inflammation and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug administration. An assessment of the frequency of the problem. Digestion. 1988;41:116–120.

10 Sakamoto N, Kono S, Wakai K, et al. Dietary risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter case-control study in Japan. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:154–163.

11 Amre DK, D’Souza S, Morgan K, et al. Imbalances in dietary consumption of fatty acids, vegetables, and fruits are associated with risk for Crohn’s disease in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2016–2025.

12 Satsangi J, Welsh KI, Bunce M, et al. Contribution of genes of the major histocompatibility complex to susceptibility and disease phenotype in inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 1996;347:1212–1217.

13 Satsangi J, Parkes M, Louis E, et al. A genome-wide search identifies potential new susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5:271–278.

14 Hugo JP, Laurent-Pig P, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. Mapping of a susceptibility locus for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5:271–278.

15 Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zomali H, et al. Association of NOD 2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603.

16 Gupta G, Gelfand JM, Lewis JD. Increased risk for demyelinating diseases in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:819–826.

17 Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Blanchard JF. The clustering of other chronic inflammatory diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:827–836.

18 Loftus EV, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, et al. Ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gut. 2000;46:336–343.

19 Loftus EV. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–1517.

20 Boyko EJ, Koepsell TD, Perera DR, et al. Risk of ulcerative colitis among former and current cigarette smokers. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:707–710.

21 Boudiaf M, Jaff A, Soyer P, et al. Small-bowel diseases: prospective evaluation of multi-detector row helical CT enteroclysis in 107 consecutive patients: CT enteroclysis is a fast, well-tolerated, and reliable imaging modality for the depiction of small-bowel diseases. Radiology. 2004;233:338–344.

22 Prantera C, Zannoni F, Scribano ML, et al. An antibiotic regimen for the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: a randomized controlled trial of metronidazole plus ciprofloxacin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:328–332.

23 Rahimi R, Nikifar S, Rezaie E, et al. A meta-analysis of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy in patients with active Crohn’s disease. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1983–1988.

24 Cheifetz A, Itzkowitz S. The diagnosis and treatment of pouchitis in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:S44–S50.

25 Thia KT, Mahadevan U, Feagan BG, et al. Ciprofloxacin or metronidazole for the treatment of perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:17–24.