Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the broad term that encompasses Crohn disease (CD), chronic ulcerative colitis (UC), and indeterminate colitis. Regardless of which specific disease entity is present, the pediatric surgeon and physicians caring for the patient are faced with difficult medical and surgical challenges. Clinical, radiographic, and pathologic features typically distinguish CD from UC. However, in up to 25% of patients with IBD, the diagnosis cannot be specified, leading to a diagnosis of indeterminant colitis.1 While medical therapies for all variants of IBD share similar strategies, the surgical care is driven by very different philosophical foundations. The surgical approach to UC is one of curative extirpation, rendering the patient free of disease through the removal of the affected intestine, generally with a proctocolectomy. The philosophy directing the operative approach to CD is much more humble, and is centered on treating the complications, but without cure. The fact that intervention is not curative must be communicated very clearly to families and patients prior to operation for CD, as the child will likely remain on medical therapy after the procedure and may require further surgical treatment at some point in the future.

Ulcerative Colitis

UC is a mucosal-based inflammatory disease limited to the colon, and has a risk of malignancy.2 The understanding that UC could be cured by removal of all colonic mucosa led to the development of operative treatment using total colectomy and proctectomy. The surgical approach has progressed from proctocolectomy with permanent ileostomy to restorative proctocolectomy, and is now routinely performed with minimally invasive techniques with or without a protective temporary ileostomy.3

Epidemiology

UC was described first in 1875 by Wilks and Moxon in the classic ‘Lectures on Pathologic Anatomy’.4 UC is predominantly diagnosed after the second decade of life. However, UC is being seen in increasing frequency in younger patients, with as many as 20% of patients becoming symptomatic before the age of 18 years.5 The incidence of UC has reportedly increased over the past three decades, and is currently reported to occur in 3.1 children per 100,000.6 Males and females are diagnosed with equal frequency. Western and Jewish societies are diagnosed with UC four times more frequently than Eastern cultures and developing countries, although this finding seems to be changing recently.7,8

Etiology

While there is much research surrounding UC and strides have been made in its underlying mechanisms, the exact etiology remains unclear.9,10 Myriad theories have been proposed including infectious etiologies, genetic relationships, immunologic disturbances, and psychologic factors. To date, none of these, either independently or in combination, has adequately explained the disease. However, each of these factors may account for certain characteristics of the disease. The genetic relationship helps to explain the racial and ethnic distribution of the disease. For instance, the relative risk for siblings with disease is 16%,11 and patients with extraintestinal manifestations have a high incidence of expression of the major antigen HLA-W27.12 Also, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies have been associated with UC. Unfortunately, evidence that these are present in unaffected family members of UC patients raises doubt about the relationship.13,14 Finally, there are genetic predictors of disease severity. Recently, NOD-2insC polymorphism has been linked to worse outcome in patients following ileoanal pull-through.15 Additionally, a single nucleotide polymorphism in chromosome 4q27,16 and mucin abnormalities have been implicated in poor outcomes in UC patients.17

An infectious etiology for the basis of UC has become a rich area for investigation as evidence increases that the balance of microbial flora plays a key role in the regulation of the normal healthy intestine.18,19 While the balance of bacterial flora may have a critical role in UC, there does not appear to be a specific infectious agent that is responsible for causing the disease.

Since UC is primarily a disease of autoimmune dysregulation, it is logical that investigation would center on the immune function of those affected. The mucosal T-cell and its regulation is the primary target of immunologic research. In addition, cytokine expression is another area of active interest. Interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6 and IL-1 receptor agonists all show imbalances in the UC population.20

Pathology

UC is a mucosal-based chronic inflammatory process that involves the rectum and extends proximally to include varying amounts of colon, often in a contiguous fashion.21 The rectum is essentially always involved, and in cases of pancolitis, the rectum is usually the most severely affected. The characteristic microscopic findings include acute inflammation with crypt abscesses, mucosal bridging, and pseudopolyp formation. As the disease becomes more chronic in nature, the thin, distended colon becomes thickened, stiff, and foreshortened.

Clinical Presentation

As noted previously, UC is most commonly diagnosed in young adults, but 4% have onset of symptoms before age 10 years and 17% present between ages 10 and 20 years.22 The initial presentation is one of persistent diarrhea, progressing to hematochezia with mucus and purulence in the stool. Tenesmus, anorexia, weight loss, and growth retardation are also common (Box 41-1). As the disease becomes more chronic, children may exhibit signs of depression and withdrawal from social and physical activities. Emotional stress has been identified as a precipitating factor in patients with relapsing disease.23 Most patients experience chronic colitis with periods of quiescence and episodic recurring exacerbations. Only a small fraction (10%) of patients have a single exacerbation followed by longstanding remission. Unfortunately, as many as 80% of children become refractory to medical therapy, and ultimately require colectomy. Fifty per cent of children diagnosed with UC in childhood will require a colectomy before age 18 years.24

In about 15% of children, the presentation is fulminant with profuse bloody diarrhea, severe cramping, and abdominal pain, fever and sepsis. Aggressive medical management will control these symptoms initially in most cases; however, 5% of patients will require urgent colectomy in the face of toxic megacolon.25

Colorectal carcinoma has been reported to occur in 3% of patients in the first ten years after the initial diagnosis, and the incidence increases to 20% per decade after the first decade. Quiescent disease does not protect from the development of cancer. In fact, young age at initial UC diagnosis may be a risk factor for colorectal carcinoma.26–28

The extraintestinal manifestations of UC are outlined in Box 41-1 and occur in 60% of children.29 Growth retardation and delayed bone growth is associated with the chronicity of inflammation in UC, while delayed sexual maturation has been shown to be related to low gonadotropin levels.30,31 Since chronic inflammation has direct effects on growth and development, adequate control of disease can relieve the growth complications that would otherwise develop.32 Arthralgias occur in about a quarter of UC patients and the knees, ankles and wrists are the most commonly affected joints. The joint symptoms often complicate the diagnostic evaluation, and may cause the child to be erroneously diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis before the gastrointestinal symptoms become obvious.

Erythema nodosum occurs primarily on the trunk and manifests as tender, red, subcutaneous nodules. Pyoderma gangrenosum is usually seen on the lower legs and presents as chronic deep ulcerations of the skin. Although much more common in adults, both may occur in children and usually resolve with treatment of the primary disease.33

Liver function testing is associated with abnormalities in up to 10% of children with UC. When abnormal liver function is identified, the patient requires close observation for the possible manifestations of primary sclerosing cholangitis.34 Anemia is common and is usually due to blood loss in the stool, but may also be related to anemia of chronic disease. Osteoporosis and malacia may be related to decreased calcium absorption associated with poor absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and/or to increased urinary loss from chronic glucocorticoid therapy. Nephrolithiasis can develop and is likely due to chronic oliguria related to inadequate intake and increased water loss in the stool.

The emotional and psychological ramifications of UC should not be dismissed. Those caring for these children will spend a great deal of time counseling, supporting, and encouraging them, and the care team should include a mental health care worker.35

Diagnosis

Although work continues on many potential candidates, serum markers for IBD have not proven to be reliable as yet. Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) has been shown to be specific for UC and absent in controls. However, it is not predictive of disease severity or course.36 Pancreatic autoantibodies, such as NOD2/CARD15 and PAB, have also been shown to correlate with disease.37

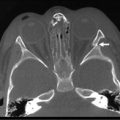

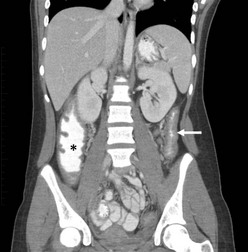

The improved visualization and characterization of disease found on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have enhanced their accuracy, and these two imaging modalities have replaced the contrast enema as a diagnostic standard.38–41 Characteristic findings have been described as a ‘lead pipe’ appearance to the colon, loss of haustral markings, and a narrow lumen (Fig. 41-1). Pseudopolyps can develop in chronic UC and may be seen on both imaging studies. Upper gastrointestinal series are only helpful to assist in differentiating UC from CD with small bowel disease.

FIGURE 41-1 This 13-year-old child has chronic ulcerative colitis and will undergo proctocolectomy and ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. This coronal CT image shows a ‘lead pipe’ appearance to the descending colon with diffuse thickening of the colon wall and a very narrowed lumen (arrow). There is also significant thickening of the wall of the cecum and ascending colon (asterisk).

Medical Management

Maintenance therapy for UC is based on immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory strategies. Treatment algorithms are based on severity of disease. Mild disease can often be controlled with 5-ASA (aminosalicylic acid) preparations such as sulfasalazine or mesalamine. Although it has not been proven to be beneficial, metronidazole is frequently added to this regimen.42 Moderate disease requires a more aggressive medical regimen to attain remission. In general, 5-ASA medications are used in conjunction with glucocorticoids, with or without 6-mercaptopurine or azathioprine. The prolonged use of steroids has severe implications, especially for children. Therefore, alternate forms of therapy are appropriate to avoid steroid dependence.43

Severe exacerbations are treated with bowel rest, intravenous fluid resuscitation or nutrition, and antibiotics. Although less frequently seen than mild or moderate disease, a small number of patients will present with acute, fulminant colitis that in some cases is associated with pancolitis and sepsis. Toxic megacolon refers to this acute, fulminant, septic colitis with massive distention of the entire colon. It is usually manifested by a distended air-filled transverse colon on plain films. High dose parenteral steroids are generally started, and cyclosporine and antitumor necrosis factor (TNF) antibodies should be considered. The approach to these patients is one of ‘rescue therapy,’ with the ultimate rescue therapy being achieved by colectomy.44,45 Perforation is an absolute indication for emergent operation, but failure to improve must be reviewed critically and objectively by the entire team to avoid allowing these children to become too sick prior to surgical intervention.

A multidisciplinary approach to the care of these children, including medical and surgical specialists, a psychologist, social worker, and nutrition specialist, is valuable in monitoring the course of therapy. Nonoperative therapy can have morbidity as well as malnutrition, growth failure, delayed sexual maturation, poor control of inflammation with persistence of symptoms, and psychological complications related to frequent stooling, fatigue, and the side effects of medications. Additionally, the immunomodulating medications that are currently most effective for controlling IBD carry their own risk of malignancy, primarily lymphoma.27 A multidisciplinary team is less likely to become invested in a specific form of therapy, and more willing to consider alternatives than a single provider working in isolation.

Surgical Management

The understanding that UC is limited to the colon, and is cured by removing the colon, has led those caring for children with this disease to consider earlier operation. In the past, the morbidity associated with proctocolectomy and permanent ileostomy was responsible for delay in seeking surgical options until after the child was severely ill and undernourished, and carried significant operative risk. As operations have become less morbid and more refined, and are associated with a better lifestyle afterwards, the threshold for colectomy has become more relaxed. Currently, operative alternatives are considered safe and effective when compared to medical therapies. With this in mind, they should be seriously considered in all children with UC, but especially those that are not responding adequately to the medical therapies. Although already mentioned, it is important to emphasize that the chronic inflammatory state of the intestinal mucosa is a risk factor for development of cancer, and youth does not protect against this risk.26–28

Preoperative Considerations

Once a decision is made for operative intervention, the preoperative preparation is important. Nutritional deficiencies must be addressed and may require a delay in the operative procedure, assuming an emergency operation is not needed. A reduction in immunosuppressive medications may be possible, although recent evidence suggests that immunosuppression is not necessarily associated with worse surgical outcomes.46 The use of a preoperative mechanical bowel preparation was once considered standard, but has recently been questioned.47–49 Currently, the need for mechanical bowel prep for colorectal surgery is not supported by the literature, although some authors continue to use it as part of their preoperative preparation. If a mechanical bowel prep is used, careful attention must be paid to the fluid and electrolyte status during the prep, as children are prone to dehydration.

Operative management of UC has undergone tremendous progress over the past 100 years. The earliest treatment was diversion with sigmoid colostomy. Later, ileostomy alone was advocated. These diversions accomplished little for the inflamed colon, and it was not until the 1940s that total colectomy was attempted. Unfortunately, there were countless ileostomy stomal complications until Brooke described the everted stoma that today bears his name.50 This technical modification allowed patients to enjoy a functional stoma, although the fluid and electrolyte derangements associated with an ileostomy continued to pose problems.

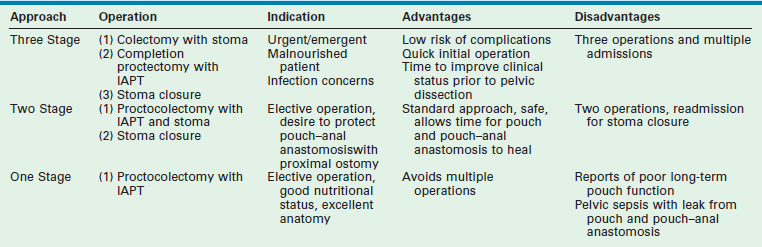

In 1947, Ravitch and Sabiston reported a restorative procedure that utilized the mucosectomy technique.51 Although this report documented the possibility of a restorative procedure, their results were sufficiently complicated to cause others to search for alternative approaches. Hence, various catheterizable pouches and stomas became the standard form of treatment after total colectomy, with or without proctectomy, and remained so until Martin described an adaptation of Soave’s endorectal pull-through used for Hirschsprung disease.52 The results following Martin’s adaptation for UC were significantly improved, but were still associated with significant issues related to stooling frequency and incontinence.53 Subsequent investigators have described differing pouch structures in attempt to create a reservoir to reduce stool frequency and continence.54–58 The current operative techniques for restorative proctocolectomy have resulted in significantly improved outcomes, and the current debate is centered on the issues outlined in Table 41-1.

TABLE 41-1

Current Issues Surrounding Operative Intervention in Ulcerative Colitis

| Issue | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Laparoscopy (compared with open) | Reduced time of recovery, less adhesions, improved scarring, less pain | Advanced laparoscopic skills needed |

| Mucosectomy (compared with stapled ileorectal anastomosis) | Complete resection of mucosa, no future surveillance | Higher incidence of incontinence and soiling rate, need for hand-sewn anastomosis |

| Pouch (compared with straight pull-through) | Improved reservoir, decreased stooling frequency and soiling, especially after operation | Pouchitis, requires surveillance |

| Temporary stoma (compared with single stage operation) | Fewer early postoperative complications | Second operation for closure |

Elective Operation

The goal of all operative interventions for UC is to render the patient free of disease with the best possible functional outcome. The quality of the outcome is determined by the patient and family, as well as the clinical situation. However, the goal in most instances is restoration of nearly normal anatomy and function.

While the philosophical goals for the surgical management of UC have not changed in the past 50 years, the operative approaches have continued to be refined. Table 41-2 outlines the advantages and disadvantages of a single operation versus a staged approach. The experience and familiarity of the treating surgeon with these various approaches directs much of the decision-making process. The first procedure described to have good functional results was the straight ileal pull-through.59 However, the straight pull-through procedure is known to be associated with persistent high–pressure peristaltic contractions associated with urgency and soiling.60 Due to this problem, most surgeons have avoided the ileal pull-through and have opted for creation of an ileal reservoir, of which the J-pouch is the most common.

Open Proctocolectomy with Ileoanal Pull-through Procedure

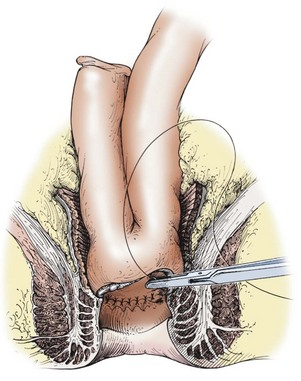

Attention is now turned to creation of the ileal J-pouch. The distal 15 cm of ileum is identified and turned back on itself. The adjacent limbs are secured to one another and the distal tip (the J limb) is opened. A linear stapling device is used to divide and secure the common wall between the two loops, thus creating the J-pouch. The pouch is oriented carefully to avoid a twist in its mesentery. In most children, the mesentery will reach easily to the pelvis if the ileal mesentery is mobilized up to the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. If necessary, the peritoneal leaflets lining the mesentery can be opened, with care taken to avoid injury to the underlying mesenteric vasculature, to allow more length on the mesentery to facilitate the pouch reaching the pelvis. Stay sutures are placed on the ileal enterotomy through which the stapler was fired. These stay sutures are delivered through the pelvis to the anus. The pouch is positioned within the rectal muscular cuff, and an end-to-end hand-sewn, single layer, interrupted pouch–anal anastomosis is completed using absorbable sutures (Fig. 41-2). A convenient loop of ileum is chosen to avoid tension on the distal anastomosis to create the loop ileostomy. Some authors prefer a completely divided end ileostomy, although reports indicate that a loop ileostomy is associated with lower complication rates at the time of later stomal closure.61 Although recent studies have shown that the procedure can be performed in a single stage without a stoma, it is our preference that this should be reserved for only the most select cases. Thus, we prefer to protect the pouch, and the pouch–anal anastomosis, with a stoma for six to eight weeks.62,63

FIGURE 41-2 In small patients, the double-stapled ileoanal anastomosis using the endoscopic circular stapler may not be possible. Also, some surgeons prefer the hand-sewn ileoanal anastomosis. The rectal mucosectomy begins approximately 5 mm above the dentate line and continues proximally to the completed pelvic dissection. The J-pouch is then pulled through the muscle cuff and anastomosed to the anal mucosa, just above the dentate line with interrupted sutures. (Copyrighted and used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, all rights reserved.)

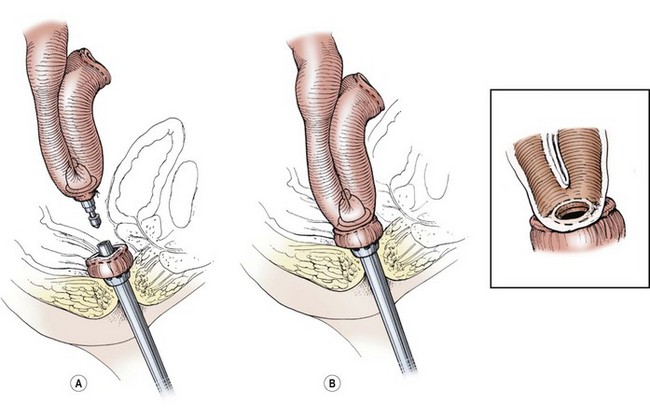

Proctocolectomy with Ileoanal Pull-through with Stapled Anastomosis

Recently, surgeons have modified the mucosectomy and hand-sewn pouch–anal anastomosis technique to take advantage of newer stapling technologies, including the circular end-to-end devices.64,65 This technique is applicable for both the open and laparoscopic approaches.66 The open operation is conducted in a similar fashion as just described. The abdominal colectomy is completed to the level of the peritoneal reflection, and the rectum is transected with a stapler. The extraperitoneal dissection is then continued to the pelvic floor, leaving a short rectal cuff of approximately 3–5 cm. The remaining rectum is then everted through the anus and out to the perineum, where it is again transected with a stapling device as close to the anus as possible, with great care taken not to injure the sphincter complex. This technique avoids the need to place the stapler into the pelvis, which universally results in a longer rectal cuff. This technique also typically leaves less than 3 cm of rectum above the dentate line. The J-pouch is created as previously described and the end-to-end circular stapler is prepared. The anvil is secured into the distal tip of the J-pouch and the pouch is positioned into the pelvis, taking care to preserve proper orientation. The hand piece of the stapler is inserted into the anus and joined to the anvil from the J-pouch (Fig. 41-3). The stapler is deployed, and the anastomosis and mucosal rings are inspected to ensure a complete anastomosis. The pelvis is filled with water, and the pouch is inflated with air to evaluate for an anastomotic leak. As there is a small amount of rectal mucosa remaining, lifelong surveillance is needed.

FIGURE 41-3 The double-stapled technique for the pouch/anal anastomosis has shown similar results as the hand-sewn technique. (A) The anvil has been placed into the pouch and is being brought close to the circular stapler, which has been introduced through the anus. (B) The anus and pouch have been approximated and the circled, stapled anastomosis performed (inset). There is usually about a 5 mm to 1 cm cuff of native rectal mucosa remaining that requires lifetime surveillance. (Copyrighted and used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, all rights reserved.)

Laparoscopic Technique

Although performed laparoscopically, the steps of the laparoscopic proctocolectomy are conducted in a similar fashion to the above description from the open operation.66 The ports can be placed in a variety of locations, and is largely determined by surgeon preference (Fig. 41-4). Although not utilized by many surgeons, recent reports have described a single site approach for this procedure.67 A typical laparoscopic approach is performed with a 10–12 mm cannula inserted in the umbilicus for a 10 mm camera. A 12 mm port is placed in the right lower quadrant at the future site of the diverting ileostomy. Usually two additional 5 mm ports, in the suprapubic and left lower quadrant, are also inserted. In very small patients in whom a stapler will not fit into the pelvis, the rectal mobilization is completed laparoscopically, and the proximal rectum is divided above the pelvis. At this point, the rectum can be everted through the anus and divided with the stapler on the outside, with great care taken to avoid injury to the sphincter complex.

FIGURE 41-4 This 8-year-old child is undergoing a laparoscopic proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis and temporary ileostomy. This view from the patient’s left side depicts placement of the ports for the operation. Note a 12 mm port is in the umbilicus through which a 10 mm, 45° angled telescope is inserted. In the right lower quadrant is another 12 mm cannula (arrow) which will become the site of the temporary ileostomy. Two 5 mm ports are in the left suprapubic area and the left mid-abdomen, and are working ports for the surgeon and the assistant.

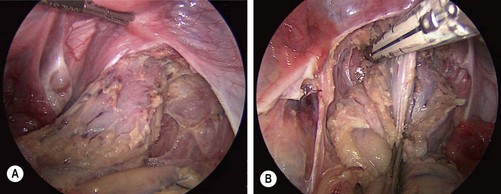

A few technical pearls are important. The colorectal dissection should be started distally, and the proximal rectum should be divided early to allow stool to be mobilized proximally (Fig. 41-5). This helps preserve a pristine pelvic dissection. The mesocolon can usually be transected using an energy source, either the ultrasonic scalpel or Ligasure. When a stapler can be introduced into the pelvis, the distal rectum is similarly transected with a stapling device, leaving just enough rectum to place the head of an end-to-end circular stapler.

FIGURE 41-5 The dissection usually starts distally on the rectum and proceeds proximally. (A) The mesorectum has been divided and the rectal wall has been skeletonized for several centimeters below the peritoneal reflection. (B) An articulating endoscopic stapler is placed across the rectum to ligate and divide it. Following ligation and division of the distal rectum, the rectum is mobilized proximally and is then exteriorized out the site of the ileostomy.

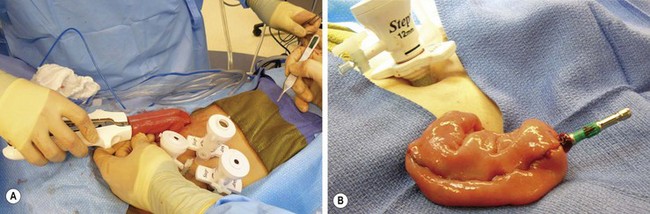

After mobilizing the colon, the specimen can then be exteriorized through the 12 mm right lower quadrant port site (Fig. 41-6). The J-pouch can be created through the intended stoma site or the umbilicus (Fig. 41-7), and is then positioned into the pelvis for an end-to-end circular stapled anastomosis (see Fig. 41-3). If an anorectal mucosectomy and hand-sewn pouch–anal anastomosis are planned with the laparoscopic approach, the laparoscopic dissection can be efficiently and safely carried to the pelvic floor, which makes for a quick and simple mucosectomy from below. This is always the back-up plan if the stapler tears the pouch or the stapled anastomosis is not secure. If desired, an ileostomy can be created according to the surgeon’s preference.

FIGURE 41-6 After ligation and division of the distal rectum, the colon has been mobilized using the ultrasonic scalpel and has been exteriorized through the right lower quadrant 12 mm port site (arrow). After the colon is separated from the ileum, the J-pouch will be reconstructed extracorporeally (see Fig. 41-7).

FIGURE 41-7 The creation of a J-pouch. (A) The J-pouch is created extracorporeally using the conventional stapler. (B) The J-pouch has been created and the anvil has been secured into the distal tip of the J-pouch in preparation for a stapled pouch–anal anastomosis.

Recently, this procedure has been described using robotic technology with excellent results, and may become more popular as experience grows.68,69 This approach may be especially applicable for the completion proctectomy following emergency subtotal colectomy.

Outcomes

Children undergoing operation for UC can be expected to have excellent outcomes.70–72 The preoperative medical therapies are tapered or discontinued appropriately. These children will predictably have five to eight stools per day until their pouch becomes functional. This stool frequency is managed with scheduled loperamide and diphenoxylate/atropine. Patients are advised to avoid caffeine, high sugar foods, and spicy foods to reduce the diarrhea. Metamucil®, or an equivalent soluble fiber, is helpful to thicken the stool to make it more controllable, and to decrease perineal irritation. Additionally, patients may be started on probiotics after continuity is reestablished to decrease the risk of pouchitis. These children should be advised to use the toilet frequently to avoid soiling. The stooling frequency is expected to improve rapidly over the first six months, but will continue to decrease over the first year. Patients are encouraged to work on holding the stool at first sensation to improve the interval between stools, and to strengthen their sphincter control, which can help decrease nocturnal leakage. Most children will eventually experience approximately four bowel movements per day, but some will continue to have nighttime bowel activity. Night-time soiling is predictable until stool frequency decreases, but unfortunately persists in a small number of patients. Long-term continence rates are over 95%, and the ability to delay a bowel movement reaches 90 minutes in many cases.

The restorative proctocolectomy is not without complications. Perioperative complications ranging from wound infection to bowel obstruction occur in as many 40% of patients. Most of these will not require operative intervention, but in one study, 7% required operation for intestinal obstruction, 14% required dilation for an ileoanal stricture, and 16% developed pouchitis requiring treatment.72

These patients require close observation and should be followed annually with pouchoscopy, unless symptomatic in the interim. Surveillance of the remnant rectal mucosa for dysplasia, and the pouch for evidence of pouchitis, should occur yearly, and biopsies should be taken at each occasion. Pouchitis is a common problem after ileoanal pull-through procedures, and is reported to some degree in nearly half of patients.70,73 Pouchitis manifests as lower abdominal pain with increased frequency of watery, foul-smelling stools and fever. It is typically a clinical diagnosis, but in some cases, pouchoscopy will be diagnostic. Contrast studies are usually not helpful. Treatment consists of metronidazole or ciprofloxacin, and in some cases, topical steroid applications. Early recurrence after stopping antibiotics is an indication for suppressive therapy with daily metronidazole or ciprofloxacin. Various scoring strategies are available to help with evaluation and management of patients with pouchitis. The most prominent system is the Heidelberg Pouchitis Activity Score.74 When pouchitis is severe or recurrent, anatomic causes should be considered, including technical problems, that can be evaluated by endoscopy, CT, MRI, or contrast study. Biopsies may also reveal evidence of CD that has only become evident after the ileoanal reconstruction. Indeed, of pouches that have to be abandoned due to poor function, at least half are diagnosed as CD.72 Although 15% of patients with a diagnosis of UC who undergo total proctocolectomy and reconstruction may end up with the subsequent diagnosis of CD, most of these patients can be managed without permanent ileostomy.75

Crohn Disease

In 1932, Crohn and colleagues described the regional ileitis that now bears his name.76 It was originally believed to be isolated to the terminal ileum, but has now been described as occurring ‘anywhere from mouth to anus’.77 CD generally presents before 35 years of age, and is most common in western countries. There has been a steady increase in its incidence since the 1950s, most prominently in developing countries and in children.78,79 The disease occurs equally in males and females, is five times more common in Caucasians than African Americans, and has a significantly higher incidence in the Jewish population.80 This relationship between ethnic and racial groups is strong evidence for a genetic predisposition for CD. However, other studies show a more random distribution of disease with little ethnic, racial, or socioeconomic relationships, raising the possibility for an environmental factor.81 CD is more common in children than UC. Moreover, the surgeon must be cognizant of the fact that this disease is lifelong, not cured by resection, and will, in most cases, require subsequent operations.

Etiology

While UC and CD have been a source of tremendous investigation, the cause of CD also remains elusive and is most likely multifactorial. The chronic, relapsing nature of the disease suggests there may be an inciting or predisposing event, as well as a factor that causes persistence of the inflammatory stimulus. The presence of an environmental factor in the susceptible host is a popular concept.82 Consideration of the intestinal microbiome as playing a causative role has gained popularity recently, and may prove to explain the increasing disease incidence in light of the increasing use of antibiotics and antimicrobial agents.83 The relationship between genetic mutations, in particular NOD2/CARD15, seems to be related to particular manifestations such as early disease onset.84 The multiplicity of theories and investigative threads lends strong support to the concept that CD is a multifaceted disease.

Clinical Presentation

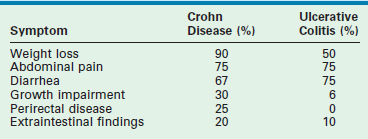

CD is typically diagnosed in young adulthood. However, its incidence in children is increasing, with approximately 20% of new cases diagnosed in children less than 15 years of age.79 In contrast to UC where diarrhea is the most common presenting symptom, the predominant presenting symptom in CD is weight loss (90%). Although acute pain may not be the symptom that prompts investigation due to its indolent onset, its presence can be elicited in up to 75% patients. The pain is typically nonspecific and is persistent. A palpable mass in the right lower quadrant may be associated with ileocolic disease, and is due to phlegmon or fibrosis. Diarrhea is present in 70% of patients, and may or may not be bloody. Hematochezia associated with CD is generally indicative of colonic disease. Growth impairment is found in a third of patients and may be multifactorial. Perirectal disease is present in 25% of patients and may be manifest as deep, nonhealing fissures, abscesses, fistulas, or large skin tags. Fistulas are often encountered and are most commonly enterocutaneous fistulas, but they can involve any site including the bladder, vagina, psoas muscle, or an adjacent loop of small or large intestine.85–87 The typical findings associated with CD and UC are outlined in Table 41-3. The extraintestinal manifestations encountered in UC may also be seen in CD, including weight loss, growth retardation, delayed puberty, skin lesions, liver disease, uveitis, arthritis, anemia and stomatitis.

Diagnosis

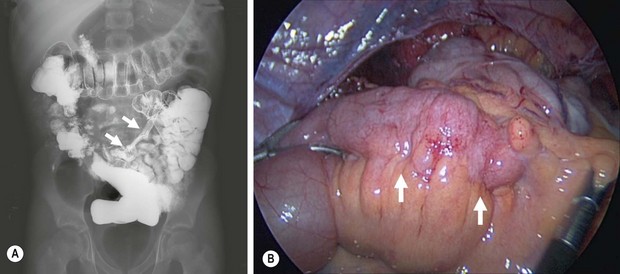

Radiographic evaluation can be very helpful in directing therapy. For example, contrast upper gastrointestinal series with small bowel follow-through can identify strictures, some with proximal dilation (Fig. 41-8). CT with water density contrast (CT enterography) has proven to be effective at evaluating CD. Recently, MR enterography has become more popular as it avoids radiation and can detect aperstilatic segments of the midgut inaccessible by endoscopy.88,89

FIGURE 41-8 (A) This upper gastrointestinal and small bowel follow-through contrast study shows a significant stricture (arrows) in the terminal ileum in a patient with persistent and symptomatic Crohn disease despite medical therapy. (B) The laparoscopic view shows active inflammation with creeping fat (arrows) along the terminal ileum in this patient.

Medical Management

The management of CD is neither entirely medical or surgical. While the mainstay of therapy for CD is medical, many children will eventually require an operation and the families should be counseled at an early stage of disease for this possibility. Surgical intervention does not represent a failure of medical therapy, but rather another method of achieving a state of remission. These children will require a lifetime of medications, and psychological support should begin at the outset. The goal of medical therapy is to achieve a quiescent state of disease and the Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index is a reliable method for following the response to therapy.90

The modern approach to medical treatment of CD is changing rapidly. The initial therapy still includes glucocorticoids in an effort to forestall the inflammatory mechanism of the disease. This initial treatment is not used for maintenance therapy, and every attempt should be made to wean steroids by 30 days. Of those unable to wean in the first 30 days, many require operation to achieve disease quiescence.91

Aminosalicylates are used in both UC and CD, and are most effective in colonic disease to decrease mucosal inflammation. Unfortunately, due to the fact these medications are most helpful in colonic disease, they are less useful in CD than in UC. Azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and methotrexate are commonly used as initial therapy when steroids do not induce remission. These drugs are known to induce remission and reduce dependence on steroids.92–94

Metronidazole is commonly used in patients with CD, especially patients with rectal or fistulous disease. Also, it is conceptualized that metronidazole is helpful for maintaining remission after resection of involved intestine. Interestingly, in one study, 75% of adults experienced relapse after discontinuing this antibiotic.95 Thus, many clinicians prefer to continue metronidazole after resection.

Monoclonal antibodies are the newest form of therapy against CD. The most popular monoclonals are directed at TNF-α. Infliximab (a mouse-human chimeric antibody), adalimumab (a human monoclonal antibody), and certolizumab are available, and are known to control steroid resistant disease. These medications can also be helpful in treating some patients with fistulous disease. More recently, agents that are more specific against CD have been developed and natalizumab (recognizing alpha-4 integrin) has shown improved efficacy.96 A top-down approach, beginning with infliximab and progressing through adalimumab, certolizumab, and natalizumab, has been suggested and is gaining favor with many gastroenterologists.97

Surgical Management

The operative approach to CD may be either open or laparoscopic, although laparoscopy has become the most popular approach since the outcomes are similar with improved cosmesis and perhaps less anxiety for the patient and family.98–100 At operation, the stepwise goal is to confirm the areas of active disease that were identified by preoperative imaging studies (see Fig. 41-8). If the disease is localized, the operative plan can be tailored to the site of disease. Options include resection of the diseased bowel with a primary anastomosis, resection with diversion, or strictureplasty. It is important to note that the primary focus of operation in CD is complete resection while preserving intestinal length, since CD is a common cause of short bowel syndrome in the adult population. The surgeon should approach any operation in a patient with CD with the goal of removing only grossly involved bowel as there is no benefit from attaining a histologic negative margin.

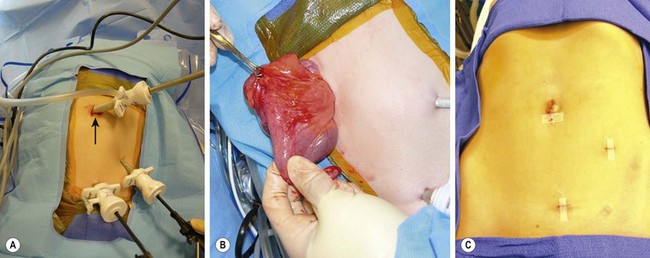

The most common operation performed for CD is ileocecectomy due to the distribution of the disease. This is typically performed as a laparoscopic-assisted approach using a 12 mm port in the umbilicus and two 5 mm ports in the left lower quadrant (Fig. 41-9A). The ileocecal junction is identified and the bowel is inspected proximally to the ligament of Treitz to confirm the affected areas. The cecum is freed from the lateral abdominal wall and, if necessary, the hepatic flexure is also mobilized. The umbilical incision can then be enlarged to a sufficient extent to exteriorize the ileocecum (Fig. 41-9B). The resection and anastomosis is then performed extracorporally and the mesenteric defect is closed. The bowel is returned to the abdomen and the incisions are closed (Fig. 41-9C). Many authors prefer a stapled anastomosis, while others feel that end-to-end anastomosis is best.101 Additionally, ileocolectomy has been performed via the single incision approach with excellent results.102

FIGURE 41-9 (A) The port placement for a patient undergoing a laparoscopic ileocecectomy is seen. A 12 mm port is placed in the umbilicus (arrow), and two 5 mm ports are introduced in the left lower abdomen and suprapubic area. (B) The diseased small bowel has been exteriorized through the umbilicus for an extracorporeal resection and anastomosis. Note the inflamed bowel and creeping fat in the exteriorized portion of the small bowel. (C) The appearance of the incisions after the laparoscopic ileocecectomy. The intestinal resection and anastomosis was performed extracorporeally through the umbilical incision.

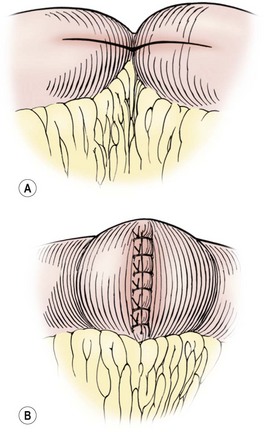

Short segment small bowel disease may not require resection, but can be managed with a bowel-preserving strictureplasty (Fig. 41-10). The operation is conducted in a similar fashion to the ileocecectomy previously described, but the area of the small bowel stricture is identified and exteriorized through the umbilicus. The strictureplasty is performed with a longitudinal incision through the stricture and then closing the enterotomy transversely, creating a wide repair of the stricture. The bowel is then replaced into the abdomen.

FIGURE 41-10 This schematic depicts a Heineke–Mikulicz strictureplasty for a very short segment of active disease or for fibrotic strictures in a patient with multicentric Crohn disease. The incision that transverses the stricture (A) is then closed in a vertical direction (B) to enlarge the intestinal lumen.

Extensive colonic disease has traditionally been treated with colectomy and permanent ileostomy. Recently, surgeons have reported segmental colectomy and anastomosis followed by more aggressive medical therapy.103,104 Pancolitis, or rectal disease, presents fewer options, since pelvic reconstruction in this setting has been associated with a high risk of complications.103 In those patients with extensive colitis or with rectal involvement, subtotal colectomy with Brooke ileostomy may be the least morbid approach, and may result in the fastest recovery and return to a healthy state. In patients with extensive colitis and rectal sparing, colectomy and an ileorectal anastomosis may be reasonable.105,106 Also, if the rectum and colon need to be removed, consideration for anal reconstruction using an ileal J-pouch is not unreasonable.

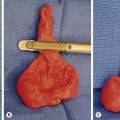

Fistulous disease can be managed directly or by diversion in the most severe cases. These lesions may be quite extensive, and CT or MRI are helpful in delineating the extent of disease. Perirectal abscesses should be drained, and fistulas are controlled with fistulotomy for the most simple cases, or a noncutting seton for the more complex (Fig. 41-11). The seton will usually control the recurring abscesses and provide symptom relief, and may be left for quite some time if it is not causing any discomfort. In patients with severe perianal manifestations, proctectomy, rectosigmoid resection, or proctocolectomy with ileostomy may be required. Simple diversion is not usually effective for healing of the affected bowel.

FIGURE 41-11 This teenager with refractory Crohn disease developed a perianal abscess that was quite painful. Examination under anesthesia confirmed the fistula and underlying abscess that was drained. A soft, noncutting silicon vessel loop (seton) was then placed. This technique allows excellent control of the perianal disease and leads to healing in most circumstances.

Outcomes

The postoperative recovery is usually good although recurrence rates increase with time and can reach 33% in long-term follow–up.107 Perioperative complications are not uncommon, and include wound infection and bowel obstruction in as many as 25%.108 Despite the inability to cure CD, the surgeon should approach the problem with optimism and embrace the opportunity to provide the patient with a period free from the symptoms.

Indeterminate Colitis

Indeterminate colitis (IC) is a distinct clinical and pathologic entity which is diagnosed in approximately 10% of IBD patients. Over time, these patients will generally be found to have either UC or CD, with differentiation to CD more likely than to UC.7,109 Not surprisingly, there is greater morbidity after colectomy and pouch–anal anastomosis in patients with the diagnosis of IC, which is due to the increased likelihood that they will eventually differentiate to CD. Additionally, adults with indeterminate colitis undergoing colectomy and pouch-anal anastomosis have a two to three times increased risk of serious postoperative complications compared to patients with UC, but still less than patients with CD.110,111 The long-term success of colectomy and pouch–anal reconstruction for indeterminate colitis is 73–85% compared with 89% for UC.112 Although these results support the consideration of performing colectomy and pouch–anal anastomosis in the setting of uncontrolled indeterminate colitis, the IC patient with features favoring CD may benefit from delayed pouch–anal reconstruction, six to 12 months after colectomy. Ultimately, operative decisions are based on the age of the patient, severity of disease, and the urgency of the operation. Children younger than age 8 years with IC should undergo colectomy and the surgeon should proceed cautiously before reconstruction is performed.

References

1. Malaty, HM, Fan, X, Opekun, AR, et al. Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among children: A 12-year study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010; 50:27–31.

2. Pohl, C, Hombach, A, Kruis, W. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease and cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000; 47:57–70.

3. Mattioli, G, Buffa, P, Martinelli, M, et al. Laparoscopic approach for children with inflammatory bowel diseases. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011; 27:839–846.

4. Wilks, S, Moxon, W. Lectures on Pathologic Anatomy. Longdon: Longmans, Green and Co; 1875.

5. Mamula, P, Telega, GW, Markowitz, JE, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in children 5 years of age and younger. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002; 97:2005–2010.

6. Jakobsen, C, Paerregaard, A, Munkholm, P, et al. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: increasing incidence, decreasing surgery rate, and compromised nutritional status: A prospective population-based cohort study 2007–2009. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011; 17:2541–2550.

7. Abraham, BP, Mehta, S, El-Serag, HB. Natural history of pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012; 46:581–589.

8. Prideaux, L, Kamm, MA, De Cruz, PP, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 27:1266–1280.

9. Ament, ME, Berquist, W, Vargas, J. Advances in ulcerative colitis. Pediatrician. 1988; 15:45–57.

10. Haller, C, Markowitz, J. A perspective on inflammatory bowel disease in the child and adolescent at the turn of the millennium. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2001; 3:263–271.

11. Selby, WS, Griffin, S, Abraham, N, et al. Appendectomy protects against the development of ulcerative colitis but does not affect its course. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002; 97:2834–2838.

12. Bouma, G, Crusius, JB, García-González, MA, et al. Genetic markers in clinically well defined patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). Clin Exp Immunol. 1999; 115:294–300.

13. Shanahan, F, Duerr, RH, Rotter, I, et al. Neutrophil autoantibodies in ulcerative colitis: Familial aggregation and genetic heterogeneity. Gastroenterology. 1992; 103:456–461.

14. Locht, H, Skogh, T, Wiik, A. Characterisation of autoantibodies to neutrophil granule constituents among patients with reactive arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and ulcerative colitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000; 59:898–903.

15. Tyler, AD, Milgrom, R, Stempak, JM, et al. The NOD2insC polymorphism is associated with worse outcome following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2012.

16. Glas, J, Stallhofer, J, Ripke, S, et al. Novel genetic risk markers for ulcerative colitis in the IL2/IL21 region are in epistasis with IL23R and suggest a common genetic background for ulcerative colitis and celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:1737–1744.

17. Tysk, C, Riedesel, H, Lindberg, E, et al. Colonic glycoproteins in monozygotic twins with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1991; 100:419–423.

18. Zella, GC, Hait, EJ, Glavan, T, et al. Distinct microbiome in pouchitis compared to healthy pouches in ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011; 17:1092–1100.

19. Michail, S, Durbin, M, Turner, D, et al. Alterations in the gut microbiome of children with severe ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012; 18:1799–1808.

20. Casini-Raggi, V, Kam, L, Chong, YJ, et al. Mucosal imbalance of IL-1 and IL-1 receptor antagonist in inflammatory bowel disease. A novel mechanism of chronic intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 1995; 154:2434–2440.

21. Finkelstein, SD, Sasatomi, E, Regueiro, M. Pathologic features of early inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002; 31:133–145.

22. Coulson, WF. Pathological features of inflammatory bowel disease in childhood. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1994; 3:8–14.

23. Mackner, LM, Greenley, RN, Szigethy, E, et al. Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Clinical Report of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013.

24. Falcone, RA, Jr., Lewis, LG, Warner, BW. Predicting the need for colectomy in pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000; 4:201–206.

25. Benchimol, EI, Turner, D, Mann, EH, et al. Toxic megacolon in children with inflammatory bowel disease: Clinical and radiographic characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008; 103:1524–1531.

26. Jess, T, Rungoe, C, Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: A meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 10:639–645.

27. Cucchiara, S, Escher, JC, Hildebrand, H, et al. Pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases and the risk of lymphoma: Should we revise our treatment strategies? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009; 48:257–267.

28. Markowitz, JM, McKinley, E, Kahn, L, et al. Endoscopic screening for dysplasia and mucosal aneuploidy in adolescents and young adults with childhood onset colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997; 92:2001–2006.

29. Lagercrantz, R, Winberg, J, Zetterstrom, R. Extra-colonic manifestations in chronic ulcerative colitis. Acta Paediatr. 1958; 47:675–687.

30. Brain, CE, Savage, MO. Growth and puberty in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1994; 8:83–100.

31. Ballinger, AB, Savage, MO, Sanderson, IR. Delayed puberty associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatr Res. 2003; 53:205–210.

32. Ezri, J, Marques-Vidal, P, Nydegger, A. Impact of disease and treatments on growth and puberty of pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 2012; 85:308–319.

33. Tavarela Veloso, F. Review article: Skin complications associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004; 20(Suppl 4):50–53.

34. Knight, C, Murray, KF. Hepatobiliary associations with inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 3:681–691.

35. Szigethy, E, McLafferty, L, Goyal, A. Inflammatory bowel disease. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010; 19:301–318.

36. Ruemmele, FM, Lachaux, A, Cezard, JP, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serological assays in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1998; 115:822–829.

37. Kovacs, M, Lakatos, PL, Papp, M, et al. Pancreatic autoantibodies and autoantibodies against goblet cells in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012; 55:429–435.

38. Gore, RM, Balthazar, EJ, Ghahremani, GG, et al. CT features of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996; 167:3–15.

39. da Luz Moreira, A, Vogel, JD, Baker, M, et al. Does CT influence the decision to perform colectomy in patients with severe ulcerative colitis? J Gastrointest Surg. 2009; 13:504–507.

40. Das, CJ, Makharia, GK, Kumar, R, et al. PET/CT colonography: A novel non-invasive technique for assessment of extent and activity of ulcerative colitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010; 37:714–721.

41. Kilickesmez, O, Soylu, A, Yasar, N, et al. Is quantitative diffusion-weighted MRI a reliable method in the assessment of the inflammatory activity in ulcerative colitis? Diagn Interv Radiol. 2010; 16:293–298.

42. Parlak, E, Dagli, U, Ulker, A, et al. Comparison of 5-amino salicylic acid plus glucocorticosteroid with metronidazole and ciprofloxacin in patients with active ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001; 33:85–86.

43. Timmer, A, McDonald, JW, Tsoulis, DJ, et al. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (9):2012.

44. Chang, JC, Cohen, RD. Medical management of severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2004; 33:235–250.

45. Hart, AL, Ng, SC. Review article: The optimal medical management of acute severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010; 32:615–627.

46. Schaufler, C, Lerer, T, Campbell, B, et al. Preoperative immunosuppression is not associated with increased postoperative complications following colectomy in children with colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012; 55:421–424.

47. Eskicioglu, C, Forbes, SS, Fenech, DS, et al. Preoperative bowel preparation for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery: A clinical practice guideline endorsed by the Canadian Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Can J Surg. 2010; 53:385–395.

48. Zmora, O, Mahajna, A, Bar-Zakai, B, et al. Colon and rectal surgery without mechanical bowel preparation: A randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2003; 237:363–367.

49. Ram, E, Sherman, Y, Weil, R, et al. Is mechanical bowel preparation mandatory for elective colon surgery? A prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. 2005; 140:285–288.

50. Brooke, BN. The management of an ileostomy, including its complications. Lancet. 1952; 2:102–104.

51. Ravitch, MM, Sabiston, DC, Jr. Anal ileostomy with preservation of the sphincter: A proposed operation in patients requiring total colectomy for benign lesions. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1947; 84:1095–1099.

52. Martin, LW, LeCoultre, C, Schubert, WK. Total colectomy and mucosal proctectomy with preservation of continence in ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 1977; 186:477–480.

53. Martin, LW, LeCoultre, C. Technical considerations in performing total colectomy and Soave endorectal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Surg. 1978; 13:762–764.

54. Parks, AG, Nicholls, RJ, Belliveau, P. Proctocolectomy with ileal reservoir and anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1980; 67:533–538.

55. Utsunomiya, J, Yamamura, T, Kusunoki, M, et al. J-pouch: Change of a method over years. Z Gastroenterol Verh. 1989; 24:249–251.

56. Wong, WD, Rothenberger, DA, Goldberg, SM. Ileoanal pouch procedures. Curr Probl Surg. 1985; 22:1–78.

57. Gemlo, BT, Wong, WD, Rothenberger, DA, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Patterns of failure. Arch Surg. 1992; 127:784–787.

58. Nicholls, RJ, Pezim, ME. Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal reservoir for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis: A comparison of three reservoir designs. Br J Surg. 1985; 72:470–474.

59. Morgan, RA, Manning, PB, Coran, AG. Experience with the straight endorectal pullthrough for the management of ulcerative colitis and familial polyposis in children and adults. Ann Surg. 1987; 206:595–599.

60. Fonkalsrud, EW, Loar, N. Long-term results after colectomy and endorectal ileal pullthrough procedure in children. Ann Surg. 1992; 215:57–62.

61. Lane, JS, Kwan, D, Chandler, CF, et al. Diverting loop versus end ileostomy during ileoanal pullthrough procedure for ulcerative colitis. Am Surg. 1998; 64:979–982.

62. Mennigen, R, Senninger, N, Bruwer, M, et al. Impact of defunctioning loop ileostomy on outcome after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011; 26:627–633.

63. Ryan, DP, Doody, DP. Restorative proctocolectomy with and without protective ileostomy in a pediatric population. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:200–203.

64. Mattioli, G, Buffa, P, Martinelli, M, et al. All mechanical low rectal anastomosis in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33:503–506.

65. Griffen, FD, Knight, CD, Sr., Knight, CD, Jr. Results of the double stapling procedure in pelvic surgery. World J Surg. 1992; 16:866–871.

66. Duff, SE, Sagar, PM, Rao, M, et al. Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: Safety and critical level of the ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Colorectal Dis. 2012; 14:883–886.

67. Fichera, A, Zoccali, M, Gullo, R. Single incision (‘scarless’) laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy with end ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011; 15:1247–1251.

68. Pedraza, R, Patel, CB, Ramos-Valadeza, DI, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery for restorative proctocolectomy with ileal J pouch-anal anastomosis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2011; 20:234–239.

69. McLemore, EC, Cullen, J, Horgan, S, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic stage II restorative proctectomy for toxic ulcerative colitis. Int J Med Robot. 2012; 8:178–183.

70. Seetharamaiah, R, West, BT, Ignash, SJ, et al. Outcomes in pediatric patients undergoing straight vs J pouch ileoanal anastomosis: A multicenter analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2009; 44:1410–1417.

71. Durno, C, Sherman, P, Harris, K, et al. Outcome after ileoanal anastomosis in pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998; 27:501–507.

72. Fonkalsrud, EW, Thakur, A, Beanes, S. Ileoanal pouch procedures in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2001; 36:1689–1692.

73. Fonkalsrud, EW. Long-term results after colectomy and ileoanal pull-through procedure in children. Arch Surg. 1996; 131:881–886.

74. Heuschen, UA, Allemeyer, EH, Hinz, U, et al. Diagnosing pouchitis: Comparative validation of two scoring systems in routine follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002; 45:776–788.

75. Mortellaro, VE, Green, J, Islam, S, et al. Occurrence of Crohn’s disease in children after total colectomy for ulcerative colitis. J Surg Res. 2011; 170:38–40.

76. Crohn, BB, Ginzburg, L, Oppenheimer, GD. Landmark article Oct 15, 1932. Regional ileitis. A pathological and clinical entity. By Burril B. Crohn, Leon Ginzburg, and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984; 251:73–79.

77. Brooke, BN. Granulomatous diseases of the intestine. Lancet. 1959; 2:745–749.

78. Perminow, G, Brackmann, S, Lyckander, LG, et al. A characterization in childhood inflammatory bowel disease, a new population-based inception cohort from South-Eastern Norway, 2005–07, showing increased incidence in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009; 44:446–456.

79. Benchimol, EI, Turner, D, Mann, EH, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of international trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011; 17:423–439.

80. Rogers, BH, Clark, LM, Kirsner, JB. The epidemiologic and demographic characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease: An analysis of a computerized file of 1400 patients. J Chronic Dis. 1971; 24:743–773.

81. Kugathasan, S, Judd, RH, Hoffmann, RG, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in Wisconsin: A statewide population-based study. J Pediatr. 2003; 143:525–531.

82. Fiocchi, C. Inflammatory bowel disease: Etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998; 115:182–205.

83. Bernstein, CN. Why and where to look in the environment with regard to the etiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2012; 30(Suppl 3):28–32.

84. Rosenstiel, P, Sina, C, Franke, A, et al. Towards a molecular risk map–recent advances on the etiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Semin Immunol. 2009; 21:334–345.

85. Heikenen, JB, Werlin, SL, Brown, CW, et al. Presenting symptoms and diagnostic lag in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999; 5:158–160.

86. El Mouzan, MI, Al Mofarreh, MA, Assiri, AM, et al. Presenting features of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease in the central region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2012; 33:423–428.

87. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; Colitis Foundation of AmericaBousvaros, A, Antonioli, DA, Colletti, RB, et al. Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: Report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007; 44:653–674.

88. Stuart, S, Conner, T, Ahmed, A, et al. The smaller bowel: Imaging the small bowel in paediatric Crohn’s disease. Postgrad Med J. 2011; 87:288–297.

89. Bruining, DH, Siddiki, HA, Fletcher, JG, et al. Benefit of computed tomography enterography in Crohn’s disease: Effects on patient management and physician level of confidence. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012; 18:219–225.

90. Otley, A, Loonen, H, Parekh, N, et al. Assessing activity of pediatric Crohn’s disease: Which index to use? Gastroenterology. 1999; 116:527–531.

91. Faubion, WA, Jr., Bousvaros, A. Medical therapy for refractory pediatric Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 4:1199–1213.

92. Mahadevan, U, Sandborn, WJ. Evolving medical therapies for Crohn’s disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2001; 3:471–476.

93. Mack, DR, Young, R, Kaufman, SS, et al. Methotrexate in patients with Crohn’s disease after 6-mercaptopurine. J Pediatr. 1998; 132:830–835.

94. Ruemmele, FM, Lachaux, A, Cezard, JP, et al. Efficacy of infliximab in pediatric Crohn’s disease: A randomized multicenter open-label trial comparing scheduled to on demand maintenance therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009; 15:388–394.

95. Rutgeerts, P, Hiele, M, Geboes, K, et al. Controlled trial of metronidazole treatment for prevention of Crohn’s recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology. 1995; 108:1617–1621.

96. Bousvaros, A. Use of immunomodulators and biologic therapies in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010; 6:659–666.

97. Yang, LS, Alex, G, Catto-Smith, AG. The use of biologic agents in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012; 24:609–614.

98. Diamond, IR, Gerstle, JT, Kim, PC, et al. Outcomes after laparoscopic surgery in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Surg Endosc. 2010; 24:2796–2802.

99. von Allmen, D, Markowitz, JE, York, A, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted bowel resection offers advantages over open surgery for treatment of segmental Crohn’s disease in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 38:963–965.

100. Gardenbroek, TJ, Tanis, PJ, Buskens, CJ, et al. Surgery for Crohn’s disease: New developments. Dig Surg. 2012; 29:275–280.

101. Resegotti, A, Astegiano, M, Farina, EC, et al. Side-to-side stapled anastomosis strongly reduces anastomotic leak rates in Crohn’s disease surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005; 48:464–468.

102. Laituri, CA, Fraser, JD, Garey, CL, et al. Laparoscopic ileocecectomy in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011; 21:193–195.

103. Makowiec, F, Paczulla, D, Schmidtke, C, et al. Long-term follow-up after resectional surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease involving the colon. Z Gastroenterol. 1998; 36:619–624.

104. Tekkis, PP, Purkayastha, S, Lanitis, S, et al. A comparison of segmental vs subtotal/total colectomy for colonic Crohn’s disease: A meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2006; 8:82–90.

105. Cattan, P, Bonhomme, N, Panis, Y, et al. Fate of the rectum in patients undergoing total colectomy for Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 2002; 89:454–459.

106. Davies, G, Evans, CM, Shand, WS, et al. Surgery for Crohn’s disease in childhood: Influence of site of disease and operative procedure on outcome. Br J Surg. 1990; 77:891–894.

107. Papi, C, Spurio, FF, Margagnoni, G, et al. Randomized controlled trials in prevention of postsurgical recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2012; 7:307–313.

108. Patel, HI, Leichtner, AM, Colodny, AH, et al. Surgery for Crohn’s disease in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 1997; 32:1063–1068.

109. Guindi, M, Riddell, RH. Indeterminate colitis. J Clin Pathol. 2004; 57:1233–1244.

110. Prudhomme, M, Dehni, N, Dozois, RR. Causes and outcomes of pouch excision after restorative proctocolectomy. Brit J Surg. 2006; 93:82–86.

111. Yu, CS, Pemberton, JH, Larson, D. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis in patients with indeterminate colitis: Long-term results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000; 43:1487–1496.

112. Wolff, BG. Is ileoanal the proper operation for indeterminate colitis: The case for. Inflam Bowel Dis. 2002; 8:362–369.