110 Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Clinical Presentation

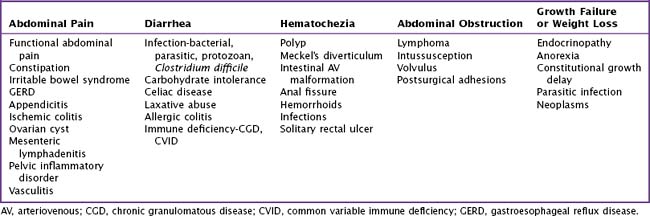

The differential diagnosis for IBD is extensive and largely depends on the presenting symptoms (Table 110-1).

Crohn’s Disease

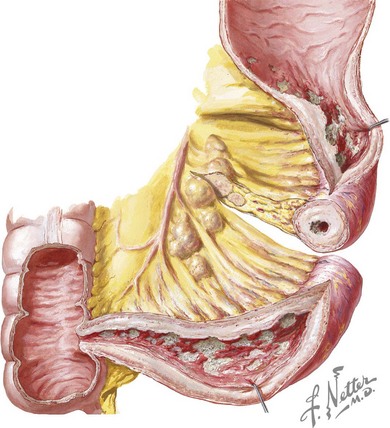

Crohn’s disease is characterized by transmural inflammation that may involve any segment of the intestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. Disease presentation is primarily determined by the location and extent of involvement. In children, the most common presenting distribution is ileocolonic disease (Figure 110-1) followed by small bowel disease alone and then colonic disease alone. Gastroduodenal disease is found in 30% of children with Crohn’s disease. Patients with ileocecal disease often present with right lower quadrant abdominal pain and diarrhea. In such patients, loops of bowel or fullness may be palpable in the right lower quadrant. Bloody stool is more common in colonic disease. Epigastric pain may occur with gastroduodenal disease. Dysphagia can be seen with esophageal involvement. Many children with Crohn’s disease have diarrhea, nocturnal defecation, low-grade intermittent fever, oral ulcers, weight loss, and decelerated growth velocity.

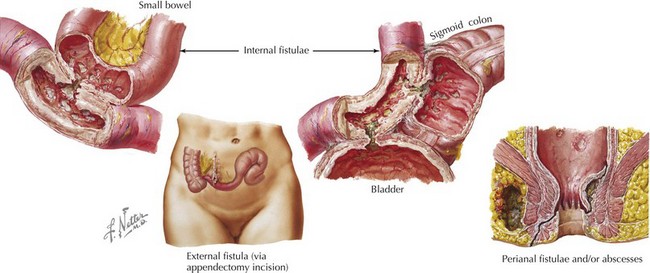

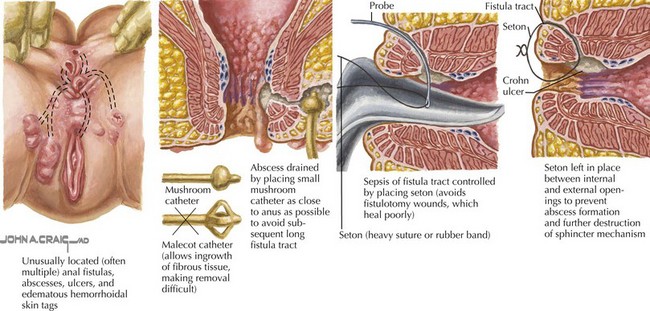

Crohn’s disease is categorized into three subtypes: inflammatory, stricturing, and fistulizing. Inflammatory disease is that described above. Stricturing disease involves luminal narrowing, which may be accompanied by prestenotic dilatation or signs of intestinal obstruction. This most commonly occurs in the small bowel but may involve the colon. Perianal or perirectal fistulae and abscesses or intraabdominal fistulae, phlegmon, or abscesses characterize fistulizing disease (Figure 110-2).

Extraintestinal Manifestations

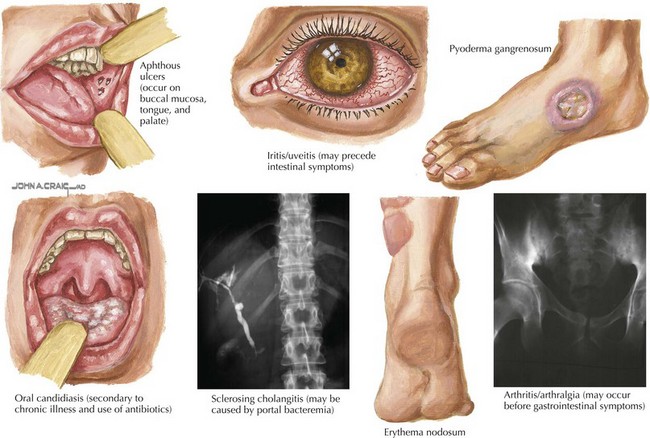

About a third of patients with IBD also have extraintestinal manifestations involving rheumatologic, cutaneous, ocular, vascular, hepatobiliary, renal, and skeletal systems (Figure 110-3). Arthralgia and arthritis are the most common extraintestinal symptoms and may involve both axial and peripheral joints. Joint manifestations may precede GI tract disease, so IBD should be in the differential diagnosis of isolated arthralgia or arthritis. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis are associated with IBD.

Evaluation And Management

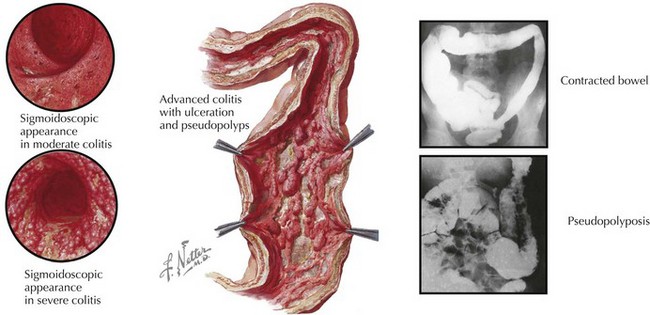

The most important diagnostic tests for IBD are upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. Findings of erythema, aphthous ulcers, cobblestone appearance, pseudopolyps, and mucosal friability are all consistent with IBD (Figure 110-4). In UC, there will be signs of inflammation starting in the rectum, extending proximally in a continuous fashion. In Crohn’s disease, rectal sparing and skip lesions are often noted. Microscopically, inflammatory infiltrates with crypt distortion and crypt abscesses consistent with chronic active inflammation are diagnostic for IBD. Occasionally, granulomas, which are consistent with Crohn’s disease and not with UC, may be noted.

In addition to upper endoscopy and colonoscopy, an upper GI series with small bowel follow-through is routinely used to evaluate for small bowel disease. In Crohn’s disease, there may be nodularity and thickened bowel loops in the terminal ileum. Occasionally, fistulous tracts and luminal narrowing can be seen. Computed tomography is often used in the emergency department to evaluate patients presenting with severe abdominal pain for a surgical abdomen, such as acute appendicitis (see Chapter 5). This may reveal thickened bowel loops, fistulous tracts, and intraabdominal abscesses in patients with IBD. Abdominal ultrasound may reveal thickening or vascular congestion within the bowel wall or intraabdominal abscess, raising suspicion for IBD. Magnetic resonance imaging is especially valuable in the context of perirectal disease and may help delineate the extent of perirectal fistulae and abscesses.

Treatment

Surgical therapy in IBD may be indicated when medical therapy fails. Surgical therapies are targeted toward the symptoms and may include small bowel resection, colectomy, abscess drainage, and seton placement in the case of perianal abscess (Figure 110-5). Indications for surgery include bowel stricture or obstruction, uncontrollable GI bleeding, intraabdominal abscess, perianal abscess, and fistula(e). Although surgical colectomy for UC is curative and eliminates the risk for future malignancy, surgery for Crohn’s disease often results in temporary relief of symptoms, and disease frequently recurs. Therefore, bowel resections should be considered carefully in Crohn’s disease patients. In addition, patients with indeterminate colitis or young patients with presumed UC require thorough repeat evaluations, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and small bowel imaging before colectomy.

Bousvaros A, Sylvester F, Kugathasan S, et alChallenges in Pediatric IBD Study Groups. Challenges in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(9):885-913.

Escher JC, Taminiau JA, Nieuwenhuis EE, et al. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in childhood: best available evidence. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:34-58.

Kleinman RE, Baldassano RN, Caplan A, et al. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition: Nutrition support for pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a clinical report of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39(1):15-27.