Inflammatory and Other Nonneoplastic Disorders of the Pancreas

Vikram Deshpande

Introduction

This chapter discusses a range of inflammatory and other non-neoplastic diseases of the pancreas, focusing on recently recognized variants of chronic pancreatitis including autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) and paraduodenal pancreatitis. In the past, a generic diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis was often sufficient, but with the recent recognition of these unique variants of chronic pancreatitis, the pathologist is required to attempt to further subclassify this disease.

A brief review of the pancreatic duct system is in order before a discussion of pancreatitis. The anatomy of the pancreatic ductal system is unpredictable because of developmental variability. The main pancreatic duct, the duct of Wirsung, carries the bulk of pancreatic secretions and drains into the duodenum at the papilla of Vater. The accessory pancreatic duct, also known as the duct of Santorini, drains into the duodenum through a separate minor papilla that is typically 2 cm cephalad to the papilla of Vater. In most individuals, the accessory pancreatic duct is nonfunctional. The minor papilla may appear as a nodule in the second part of the duodenum and could be mistaken for a polyp.

Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory disease of the pancreas that is characterized clinically by acute abdominal pain and increased levels of serum amylase and lipase.1,2 The incidence of this disease has increased in the past 2 decades, and acute pancreatitis accounts for more than 200,000 hospital admissions every year in the United States. Eighty percent of these episodes are mild and resolve without serious morbidity, but in 20% of cases, the episodes are more severe and are associated with substantially increased morbidity and mortality.1,2 This disease is seldom seen by the surgical pathologist, although it is frequently encountered at autopsy. Very occasionally, pancreatic neoplasms manifest as acute pancreatitis, and foci of resolving acute pancreatitis may be seen adjacent to neoplasms of the pancreas.

Clinical Features

Acute pancreatitis is characterized by acute constant pain that typically radiates to the back. In cases of severe acute pancreatitis, the necrosis tracks into the periumbilical region (Cullen sign) and abdominal flank to cause bluish cutaneous lesions at these sites.1,2 The diagnosis is confirmed by demonstrating elevations in serum amylase and lipase. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is used to confirm the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, demonstrate local complications such as fluid collections and necrosis, and score the severity of the disease.3

There is a wide spectrum of severity, with some episodes of acute pancreatitis being mild and self-limited, requiring only brief hospitalization, and those most severely affected developing persistent hypovolemia and multiorgan dysfunction. A number of scoring systems are used to predict the severity of the disease. The most common is the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, the Ranson criteria, and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score. The Atlanta classification divides the disease into two grades: mild (80% of cases) and severe (20% of cases).4

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The two most common triggers of acute pancreatitis are obstruction of the common bile duct by stones and alcohol abuse.1,2 Together, they account for approximately 80% of cases of acute pancreatitis in Western countries. Bile stone-induced pancreatitis typically affects elderly women and is caused by gallstone migration and subsequent pancreatic duct obstruction. Although gallstones are the most common cause of biliary obstruction, other forms of obstruction, such as periampullary tumors and neoplasms involving the head of the pancreas, may also provoke acute pancreatitis.

Alcohol-related acute pancreatitis is more frequently seen in middle-aged men. Experimental studies have implicated alcohol in transient increases in pancreatic exocrine secretions, contraction of the sphincter of Oddi, and direct toxic injury to acinar cells. However, the relationship between alcohol and pancreatitis is not completely understood. Acute pancreatitis develops in only a small fraction of alcohol abusers (>80 g daily intake).5 Clearly, other genetic and environmental factors play a major role in the development of alcohol-related acute pancreatitis.

Less common causes of acute pancreatitis are listed in Box 39.1. In a substantial minority of cases the cause is unexplained. In such patients, genetic testing for mutations, including the cationic trypsinogen gene (PRSS1), serine protease inhibitor Kazal type I (SPINK1), or cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), may provide an explanation for recurrent acute pancreatitis (see later discussion).

Although the precise pathogenesis is controversial, it is nonetheless believed by most investigators that acute pancreatitis is caused by unregulated activation of pancreatic trypsin: The trypsin leads to both autodigestion and local inflammation. After activation of trypsinogen to active trypsin, other pathways and enzymes in the pancreas such as elastase, complement, and kinin systems are activated. The inflammation is further propagated by the production of mediators such as interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, and IL-8, which are produced by neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes that are attracted to the diseased pancreas.

Pathologic Features

The pancreas typically appears swollen and pale. With mild acute pancreatitis, multiple tiny spots of opaque white fat necrosis are seen on the surface of the pancreas (Fig. 39.1).6 Foci of intrapancreatic fat necrosis may also be seen. The amount of intrapancreatic fat varies considerably among individuals, and the presence of intraparenchymal fat necrosis is appreciable only in those with a moderate amount of intrapancreatic fat. In cases of severe acute pancreatitis, large confluent areas of necrosis are identified as well as hemorrhagic areas.

Histologically, the changes of acute pancreatitis have been characterized in autopsy material. In mild forms of acute pancreatitis, the disease is concentrated in the interlobular septa.6 With time, these foci of fat necrosis are replaced by foamy macrophages, and ultimately by fibrosis (Fig. 39.2). In the more severe examples of acute pancreatitis, there is diffuse necrosis involving the acinar and ductal tissue accompanied by acute inflammatory cells. These foci of necrosis may liquefy to form a pseudocyst; less commonly, they may become infected, a complication associated with high mortality. Damage to the vasculature results in diffuse hemorrhage (hemorrhagic pancreatitis). Well-characterized examples of acute pancreatitis triggered by atheroembolism have also been reported.7

Therapy

The treatment for mild forms of the disease is largely supportive and includes fluid resuscitation.1,2 More severe cases require aggressive fluid resuscitation and antibiotics. Pancreatic necrosis and infection are two important local complications of the disease, with the latter being one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality. When infection is suspected, a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is performed to obtain material for microbiology studies.

Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis is a fibroinflammatory disorder in which the pancreatic acinar compartment is replaced by fibrosis, eventually leading to exocrine insufficiency.8–10

Until recently, acute and chronic pancreatitis were viewed as distinct diseases. However, they have now come to be viewed as a continuum.10 This view is supported by the observation that chronic pancreatitis eventually develops in some patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis, and the two diseases share etiologic factors such as alcohol abuse and certain germline mutations.

A number of classification schemes for chronic pancreatitis have been proposed, including the Marseille classification of 1963, the revised Marseille classification of 1984, the Marseille-Rome classification of 1988, the Cambridge classification of 1984, the Zurich classification of 1997, and the Japan Pancreas Society classification of 1997.9 However, there is no single widely accepted system, and most of these schemes are not helpful in clinical practice. Notably, these classification schemes were published before the recognition of autoimmune pancreatitis. Furthermore, many of them focus on the distinction between acute and chronic pancreatitis and pay little attention to histopathologic changes; hence, they are of little interest to the anatomic pathologist. In many circumstances, the composition of the inflammatory infiltrate and the pattern of fibrosis provide clues to the etiology of the disease.

Confirming a Diagnosis

Histology remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis; however, biopsy is impractical in most situations. Histology is typically available only when a tumefactive lesion is identified. Therefore, the most practical and efficient way of establishing a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is by demonstrating a reduction in bicarbonate in a duodenal aspirate after secretin stimulation and by detecting abnormalities of the pancreatic ductal system on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).8–10 The presence of chunky intrapancreatic calcifications on plain radiographs or CT scans is also diagnostic of chronic pancreatitis, although these features are seen only in a minority of cases.

Alcoholic Pancreatitis

The most common cause of chronic pancreatitis in developed nations is alcohol ingestion, which accounts for approximately 70% to 95% of cases (Box 39.2). However, clinically apparent chronic pancreatitis develops in only 10% of patients with alcohol abuse.8,9 Therefore, it is likely that additive factors play a role in the development of alcohol-related chronic pancreatitis. Cigarette smoking is an independent, dose-dependent risk factor for chronic pancreatitis.11 It has recently been appreciated that the contribution of alcohol abuse to chronic pancreatitis may have been overestimated, and that cigarette smoking may contribute significantly to the development of the disease, because the vast majority of patients who abuse alcohol are also cigarette smokers.11

Germline genetic defects have a role in the development of chronic pancreatitis, either as the primary driver, as in hereditary pancreatitis, or as a disease modifier, as in individuals with mutations in the CFTR (see later discussion). It is likely that alcohol-related pancreatitis is a multifactorial disease and that environmental and genetic factors play major roles in modifying the disease.

Clinical Features

Alcohol-related chronic pancreatitis is predominantly a disease of men and usually manifests in the fourth and fifth decades of life.8–10 Epigastric pain is the overriding early symptom. The pain typically radiates to the back and can be partially relieved by sitting up and leaning forward. The presentations can be categorized into four groups: (1) acute or recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis, (2) constant pain, (3) symptoms related to local complications of the disease such as pseudocyst formation, and (4) symptoms related to exocrine or endocrine insufficiency. Exocrine insufficiency in the form of steatorrhea develops late in the disease, after more than 95% of the acinar tissue has been lost.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis is not well defined, although three hypotheses have been proposed.12

Ductal Obstruction Theory

The ductal obstruction theory states that alcohol increases protein concentration in the pancreatic fluid and these proteins plug the pancreatic ducts.13 In fact, such proteinaceous plugs are frequently observed in individuals with significant alcohol exposure. These plugs may also calcify and further contribute to the development of chronic pancreatitis. Although this theory has been ignored in recent years, interest in it has been revived since the discovery of the association between CFTR mutations and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis; specifically, individuals with cystic fibrosis and CFTR mutations show proteinaceous plugs.

Toxic Metabolic Theory

The toxic metabolic theory is based on experimental evidence to suggest that alcohol exerts a direct toxic effect on acinar cells. Similar to the liver, the pancreas metabolizes ethanol via both oxidative and nonoxidative pathways, generating the metabolite acetaldehyde and fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs), respectively.14 Experimentally, alcohol has been shown to increase the content of the digestive enzymes trypsinogen and lipase, and this increase is accompanied by a fragility of the organelles that contain these enzymes.15 The net effect is an increased likelihood of premature activation of these digestive enzymes and autodigestion of the pancreas. The most compelling evidence that acinar cells play an important role in the development of chronic pancreatitis is the association between mutations in PRSS1 and pancreatitis.

Necrosis-Fibrosis Theory

Traditionally, chronic alcoholic pancreatitis was believed to be “chronic” at initiation. The necrosis-fibrosis theory suggests that chronic pancreatitis is a consequence of repeated episodes of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatic stellate cells are believed to play a critical role in the development of fibrosis.14 The pancreatic stellate cells are activated either by cytokines (autocrine or paracrine) or by direct effects of alcohol and its metabolites. This persistent activation is believed to be responsible for fibrosis, a defining feature of chronic pancreatitis.

Pathologic Features

The hallmark of chronic pancreatitis is fibrosis, although in the early stages it may be unevenly distributed. Most surgical specimens show diffuse fibrosis and significant induration.16–18 The gland may appear enlarged, but in the late phase of the disease the pancreas is shrunken. Cysts of varying sizes are identified both within and outside the pancreas. The extrapancreatic cysts invariably represent pseudocysts; the intrapancreatic cysts are either pseudocysts or retention cysts.16 Another hallmark of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis is calcification, both within the main pancreatic duct and in the parenchyma. The main pancreatic duct may be obstructed and dilated, although strictures may also be identified. Tapering stenosis of the common bile duct is present in a minority of cases.

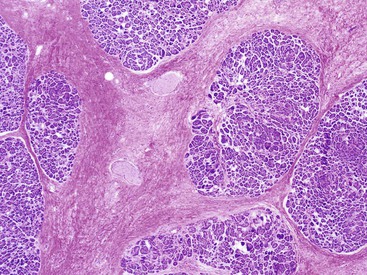

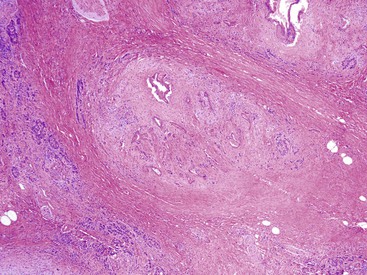

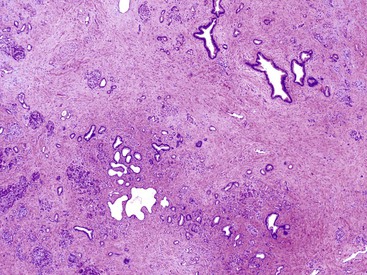

Histologically, alcohol-related pancreatitis exhibits varying degrees of atrophy of the exocrine and endocrine components along with calcification and fibrosis (Fig. 39.3).16–18 In the late phase of the disease, overt interlobular fibrosis is seen, and intralobular fibrosis is also invariably present. The fibrosis is relatively acellular, but fibroblasts and myofibroblasts may be seen. Although much of the acinar component may be depleted, foci of well-preserved acinar tissue are seen interspersed. Some of the pancreatic ducts are dilated; they are filled with proteinaceous material and sometimes calculi (Figs. 39.4 and 39.5).

An inflammatory component is invariably identified, but the degree of inflammation is significantly less than that seen in AIP. Most of the inflammatory cells are small lymphocytes, and lymphoid aggregates are also occasionally present. Plasma cells are usually inconspicuous. In contrast to AIP, periductal lymphocytic accentuation is rarely identified. Intraneural and perineural lymphocytic aggregates are usually prominent. The small lymphocytes are predominantly T cells, although scattered B cells are also present. When neutrophils are identified they are usually seen adjacent to pseudocysts and residual foci of acute pancreatitis; intraductal aggregates of neutrophils are uncommon.

In the early stages of chronic pancreatitis, the islets of Langerhans are usually normal in appearance. In the late phase, the pancreatic islets may appear remarkably prominent. This apparent prominence of the endocrine component is primarily related to the preferential loss of acinar tissue. It may occasionally be difficult to distinguish this “pseudohypertrophy” of the endocrine component from a pancreatic endocrine microadenoma. Immunohistochemical stains for insulin and glucagon can assist in making this distinction: Pseudohypertrophic islets show an intimate admixture of insulin- and glucagon-producing cells, whereas a microadenoma is entirely negative for both markers or may show diffuse reactivity for glucagon. Ductular-insular complexes may be seen, but this is a relatively nonspecific finding. In the very late phase of the disease, there is an appreciable decrease in the endocrine component.

Lesions of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) are frequently identified in resections from patients with chronic pancreatitis. Most of these are low grade (grade 1 and grade 2); PanIN3 lesions are distinctly uncommon. The risk of carcinoma in the setting of chronic pancreatitis is discussed later.

Differential Diagnosis

Chronic Pancreatitis versus Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

Distinguishing a well-differentiated pancreatic adenocarcinoma from chronic pancreatitis can be one of the most difficult decisions a pathologist encounters.19 Making this distinction on the basis of a frozen section or needle biopsy specimen exponentially increases the level of difficulty. Nonetheless, attention to the following four features is key to making this distinction (Table 39.1).

Table 39.1

Features to Distinguish Chronic Pancreatitis from Well-Differentiated Adenocarcinoma

| Chronic Pancreatitis | Invasive Ductal Adenocarcinoma | |

| Lobular architecture maintained | Yes | No |

| Nonlobular distribution of glands | No | Yes |

| Nuclear variation >4 : 1 within a gland | No | Yes |

| Nuclear membrane irregularities | No | Yes |

| Cytoplasm | Dense, eosinophilic | Pale, vacuolated |

| Perineural invasion | No | Yes |

| Association of ducts with arteries | No | Yes |

Location of Ducts and Glands.

As a general rule, ducts organized in well-circumscribed lobules are benign, whereas atypical ducts scattered in the interlobular septa or suspended within peripancreatic fat suggest a malignant process (Fig. 39.6). Glands located within lobules, regardless of the degree of atypia, should suggest a “benign” interpretation (Fig. 39.7). Other than an occasional large duct, few other ducts are seen in the interlobular septa in chronic pancreatitis. Furthermore, unlike ducts in the liver, those in the pancreas do not accompany arteries, so the presence of a duct adjacent to an artery is highly suspicious for a pancreatic adenocarcinoma.20 The presence of perineural invasion is diagnostic for carcinoma, although it is important to ensure that the gland is actually infiltrating the perineural space. Vascular invasion is also diagnostic for carcinoma.

Desmoplastic Stroma.

The desmoplastic reaction, a peculiar mesenchymal proliferation composed of fibroblasts suspended within a basophilic stroma, is an important feature of ductal adenocarcinoma. However, distinguishing desmoplastic stroma from the stroma of chronic pancreatitis can be quite subjective.

Cytoplasmic Features.

The identification of cytoplasmic features is underemphasized in the diagnosis of malignancy. Benign ducts show a dense eosinophilic cytoplasm, whereas many (but not all) adenocarcinomas, especially the well-differentiated carcinomas, show abundant pale cytoplasm, giving the cells a low nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N : C) ratio. A low N : C ratio is a common finding in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Nuclear Features.

The two most reliable nuclear features of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma are markedly irregular nuclear outlines and anisonucleosis (>4 : 1 variation in nuclear size). The variation in nuclear size is appreciable on paraffin and frozen sections, but the nuclear irregularities are less obvious on these preparations. Both features, however, are reliably identified on cytology preparations.

A number of immunohistochemical and molecular markers can help with this distinction, and these are covered in great detail in Chapter 40.

Chronic Alcoholic Pancreatitis versus Autoimmune Pancreatitis

The type 2 variant of AIP is most likely to be confused with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. The two hallmarks of type 2 AIP—a dense periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and granulocytic epithelial lesions—are seldom seen in alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. It is important to emphasize that type 2 AIP is not a immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related disease and is not associated with elevated serum or tissue levels of IgG4, although mild elevations may be seen.

In contrast, distinguishing the type 1 variant of AIP from alcoholic pancreatitis is relatively straightforward. Histologically, virtually all cases of type 1 AIP demonstrate a triumvirate of histologic features : (1) a dense and diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, unlike the patchy lymphocytic infiltrate of alcoholic pancreatitis; (2) storiform-type fibrosis, unlike the acellular fibrosis of chronic alcoholic pancreatitis; and (3) obliterative phlebitis. Furthermore, almost all cases of type 1 AIP show greater than 50 IgG4-positive plasma cells per high-power field (HPF). However, difficulties arise when interpreting needle biopsy specimens. AIP does not uniformly involve the pancreas, and some biopsies may not demonstrate the full spectrum of histologic findings. In such cases, correlation with clinical and radiologic features as well as serum IgG4 levels is required.

Chronic Pancreatitis and the Risk of Pancreatic Cancer

Chronic pancreatitis has consistently been shown to be a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. In a study of 2015 patients with chronic pancreatitis, a cumulative risk for pancreatic cancer of 4% at 20 years was found.21 Subsequent studies confirmed this increased risk for pancreatic cancer in patients with chronic pancreatitis.22,23 One of the concerns with these studies is the potential for misdiagnosis of pancreatic cancer as chronic pancreatitis, which inflates the risk of malignancy. However, because the association between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer persists for several years after the initial diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, this is not believed to represent a confounding factor. In comparison to chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, hereditary pancreatitis carries a far higher risk of pancreatic cancer (approximately 35% during a lifetime).

Therapy

The goals of treatment are to relieve pain, prevent recurrent attacks of acute pancreatitis, and manage the metabolic consequences such as maldigestion and diabetes. Surgery or endoscopic intervention is required to relieve intractable pain or to address specific complications such as pseudocysts. The objective of surgery (pancreatojejunostomy) is to decompress the pancreatic duct (which relieves pain) and to preserve as much of the pancreas as possible (to preserve pancreatic islets).

Genetics of Pancreatitis

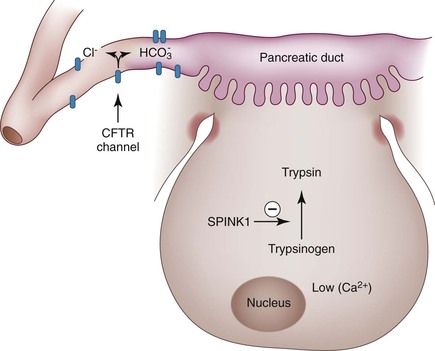

There is growing evidence that a significant proportion of patients with apparently idiopathic acute or chronic pancreatitis have underlying genetic abnormalities. Among the genes that predispose an individual to chronic pancreatitis, three are associated with defects in the activation of trypsinogen: PRSS1, SPINK1, and chymotrypsin C (CTRC).24–28 This is not surprising, because one of the fundamental events in the development of pancreatitis is the activation of trypsinogen to trypsin (Fig. 39.8). Trypsin is associated with some unique enzymatic features, because it can both self-activate and deactivate itself. The mutations in PRSS1 that are associated with the development of chronic pancreatitis either cause premature activation of this enzyme or abrogate the inactivation.28 The most common mutation in PRSS1, R122H, abrogates the ability of trypsin to inactivate itself and also enhances trypsinogen autoactivation. The SPINK1 gene encodes for a trypsin inhibitor, and loss of function mutations of this gene abrogate the ability of the protein to inhibit activation of trypsin.26 Other genes implicated in chronic pancreatitis are calcium-sensing receptor, CTRC,27 and CFTR.29

With rapid advances in technology, it is relatively easy to identify mutations in genes that contribute to the development of pancreatitis. Although mutations in each of these genes have unequivocally been linked to pancreatitis, many of the mutations are disease neutral, and some could even be protective. Furthermore, the penetrance is extremely low, in some cases less than 1%. Therefore, the interpretation of these genetic tests is increasingly complex. With some exceptions (discussed later), testing for mutations in unselected patients with suspected pancreatitis is not recommended.25

Trypsinogen Mutations

Since the discovery of the PRSS1 gene, more than 20 mutations have been identified. The clinical relevance of the R122H mutation is supported by data from a transgenic model.30 Gain-of-function mutations, especially R122H and N29I, show a high penetrance (80%). This, coupled with the increased risk of pancreatic cancer (35-fold), supports the use of diagnostic testing for these mutations in young patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis.25

SPINK1 Mutations

The most common SPINK1 mutation, N34S, has a high frequency (approximately 2%) in the general population and is associated with a very low penetrance.26 Another mutation, c.27delC, is associated with a severe phenotype but also shows a relatively low penetrance of 29%.26 Consequently, SPINK1 mutations are thought to be disease predisposing or disease modifying rather than directly causing disease.

CFTR Mutations

Although chronic pancreatitis develops in a substantial majority of patients with cystic fibrosis, a small but distinct group of mutations is associated with isolated involvement of the pancreas (i.e., without pulmonary and other typical manifestations). The mutations seen in this setting are distinct from those associated with cystic fibrosis, and the patients typically do not show other clinical features of cystic fibrosis. Furthermore, their sweat chloride levels are normal.10,24,29 Unlike patients with cystic fibrosis, these patients are diagnosed in adulthood.

The association between CFTR mutations and chronic pancreatitis was first identified more than a decade ago.29 In one study, 43% of patients with idiopathic recurrent acute pancreatitis and 11% of patients with chronic pancreatitis carried CFTR mutations in one or both genes.24 Nonetheless, of the more than 1600 CFTR mutations that have been identified, only a minority are associated with disease. Therefore, genetic testing for CFTR mutations in individuals with acute or chronic pancreatitis is not recommended; the test of choice, even in this era of genomics, is a sweat chloride test.25 Genetic testing is recommended only if full-blown cystic fibrosis (as opposed to isolated involvement of the pancreas) is suspected.

Hereditary Pancreatitis

Clinical Features

Hereditary pancreatitis is an autosomal dominant disease that typically manifests with recurrent attacks of acute pancreatitis in childhood (the first and second decades of life).28 This is an uncommon cause of chronic pancreatitis, accounting for fewer than 2% of all cases. The disease affects men and women equally. A diagnosis of hereditary pancreatitis should be suspected in any individual in whom chronic pancreatitis develops at an early age (<25 years). In 80% of cases, hereditary pancreatitis is caused by a gain-of-function mutation in the PRSS1 gene (see earlier discussion). Although 20 mutations have been identified, the 2 most common mutations are R122H and N29I. The penetrance of these mutations is high, and approximately one half of these patients progress to chronic pancreatitis. In a study of 200 patients with hereditary pancreatitis, the cumulative risk of pancreatic carcinoma at 50 years of age was 11% for men and 8% for women; at 75 years, it was 49% for men and 55% for women.31 The type of genetic mutation did not correlate with the risk of cancer.31

Pathologic Features

Limited information is available on the pathologic changes of hereditary pancreatitis. It appears that the disease is histologically similar to alcoholic chronic pancreatitis with periductal and interlobular fibrosis.16 The dilated ducts show both protein plugs and calculi, although some cases are associated with a periductal collar of inflammation (Fig. 39.9).16

Pancreatic Divisum

Pancreatic divisum occurs when the ventral and dorsal pancreatic ducts fail to fuse during development.32,33 An “incomplete” pancreatic divisum implies that there is a narrow communication between the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts. Pancreatic divisum is by far the most common congenital variation of the pancreatic ductal system, occurring in approximately 10% of individuals.32,33

Most individuals with pancreatic divisum are asymptomatic, and pancreatitis develops in only a minority. The disease manifests primarily in adults, and both sexes are affected. Pancreatic disease in the form of acute or chronic pancreatitis is in part caused by inadequate pancreatic drainage through a narrow dorsal pancreatic duct. ERCP reveals a short ventral duct and a main pancreatic duct that communicates with the dorsal duct and drains into the duodenum near the minor papilla.

One of the most controversial aspects of this disease is the difficulty in demonstrating a causal relationship between pancreatitis and this anatomic variation of the ductal system. There is increasing evidence to suggest that pancreas divisum alone is insufficient to precipitate pancreatitis. A recent study showed no difference in the prevalence of pancreatic divisum between patients with idiopathic pancreatitis and a control population, 5% and 7%, respectively.34 However, the authors found that the prevalence of pancreatic divisum in patients with pancreatitis and mutations in CFTR, SPINK1, or PRSS1 was 47%, 16%, and 16%, respectively.34 Therefore, only a small proportion of patients with pancreatic divisum would benefit from decompression of the dorsal pancreatic duct, a procedure that can be performed endoscopically.

Autoimmune Pancreatitis

Definition and Historical Aspects

AIP is a mass-forming inflammatory lesion of the pancreas that may mimic pancreatic carcinoma.34–36 It is only in the last 2 decades that this disease has received the attention it deserves. Previously, these cases were diagnosed nonspecifically as chronic pancreatitis. In retrospect, approximately 25% of pancreatic resections that lack evidence of malignancy may represent AIP.37

AIP was first described by Sarles and colleagues in the 1960s.38 They described four cases of chronic pancreatitis in patients with steatorrhea and obstructive jaundice.38 Histologically, the pancreas showed a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. Although the histologic descriptions were limited, it is likely that these cases represented AIP. Little progress was made in the subsequent 3 decades, although there were similar sporadic case reports in the literature. Kawaguchi and co-workers are credited with the first modern histopathologic description of this entity.39 They described two men with obstructive jaundice and histologic features that are now considered typical for AIP.39 The term autoimmune pancreatitis was coined by Yoshida and colleagues in a case report in 1995 and this term is now the preferred designation.40,41

A major milestone in understanding of this disease came with the apparently serendipitous discovery of its association with elevated levels of serum IgG4.42 Shortly afterward, it was established that the inflamed pancreas shows a substantial increase in IgG4+ plasma cells.43–46 It was subsequently realized that a sizeable number of patients with AIP also exhibit either synchronous or metachronous fibroinflammatory mass lesions in other organs, including the liver and biliary tract.45,47 This multifocal systemic fibroinflammatory disease is now termed IgG4-related disease.36 In fact, AIP is only one manifestation of IgG4-related disease, and in an attempt to highlight this relationship, some authorities advocate use of the term IgG4-related pancreatitis.40

Subtypes

AIP is not a homogenous entity, because the disease can be clearly segregated into two distinct clinicopathologic subtypes: AIP type 1 and AIP type 2.36,48–53 AIP type 1 is an IgG4-related disease, whereas the type 2 variant is not. There is significant overlap in the clinical and radiologic features of these two variants (see later discussion).36,48–52,54

Clinical Features

AIP is an uncommon disorder. A recent nationwide survey in Japan identified an overall prevalence rate of 45.1 cases per 100,000 patients, with a threefold increase in the number of cases during a decade.55 Although no data are available from North America, this disease is significantly less common than pancreatic carcinoma.

Both the gender ratio and the mean age at presentation vary according to the histologic subtype. Patients with type 1 AIP tend to be older (in their seventies) than patients with the type 2 variant (in their fifties).35,43,48,49,52,54–56 Most patients with type 1 AIP are male, whereas the gender ratio for type 2 AIP is approximately 1 : 1. There is considerable overlap between the demographic and clinical features of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis and those of the type 2 variant of AIP, although the former entity tends to be more common in men.

There appear to be geographic variations in the incidence of the two subtypes: the type 2 variant is extremely uncommon in Asia but constitutes almost half of all cases of AIP in series from Europe and North America.54

Obstructive jaundice and weight loss develop in patients with type 1 AIP.48–50,52,54, 56–58 These symptoms, along with a mass on imaging, make the distinction of this disease from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma extremely problematic. Other non-neoplastic lesions that mimic pancreatic cancer are listed in Box 39.3. Other presenting symptoms of patients with type 1 AIP include fatigue and recent onset of diabetes mellitus. Abdominal pain is uncommon, although some patients may complain of vague abdominal pain. Patients with type 1 AIP may have other manifestations of IgG4-related disease, either synchronously or metachronously.48–50,52,54,56–58 One of the more common extrapancreatic manifestations of type 1 AIP is a painless unilateral or bilateral swelling of the submandibular salivary gland. In fact, in an individual with painless obstructive jaundice, bilateral enlargement of the submandibular salivary glands is strongly suggestive of IgG4-related disease (AIP).59

Patients with type 2 AIP have abdominal pain, although the pain is rarely severe enough to suggest acute pancreatitis.48–50,53,55,56–58 In comparison to type 1 disease, a smaller proportion of patients with type 2 AIP have obstructive jaundice at presentation.

Although AIP is an uncommon cause for either acute or chronic pancreatitis, more than 33% of patients with this disease have symptoms that mimic other forms of acute or chronic pancreatitis.57

Serum Markers

Elevated serum IgG4 is the most robust biomarker for this disease.42,60 This test is fairly sensitive for type 1 AIP, and is elevated in 80% of cases, but its specificity, particularly in an unselected population, is low.50,60 A recent survey during a 1-year period identified 59 patients with elevated levels of serum IgG4. Among these, only 10% had unequivocal evidence of IgG4-related disease.61 An even more worrisome observation is that approximately 10% of patients with pancreatic cancer show elevated levels of serum IgG4. The specificity of this test is somewhat improved when the threshold is set at 280 mg/dL (two times normal). Patients with type 2 AIP only occasionally show elevated levels of serum IgG4, and there is currently no reliable biomarker for recognition of this variant.51

A number of other immunologic abnormalities are identified in patients with AIP. These include positive antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and elevated gammaglobulin levels. A variety of other antibodies have been identified, including anti-lactoferrin and anti–carbonic anhydrase antibodies, although these are not specific and are not used in clinical practice.35,62

A novel autoantibody against a plasminogen-binding protein peptide, although it has yet to be validated, has shown a high sensitivity (94%) and the assay is positive in only 5% of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.62,63

Radiology

During the last decade, radiologists have greatly improved their ability to identify AIP and distinguish it from pancreatic carcinoma. Nonetheless, we continue to see pancreatic resections for AIP.

On imaging, three patterns of AIP are recognized: diffuse, focal, and multifocal.64–66 The diffuse form of the disease (Fig. 39.10) is the most common type; the pancreas appears enlarged and “sausage shaped.” Among these patterns, the focal form of disease is most likely to be confused with pancreatic carcinoma.

The affected regions of the pancreas are hypoechoic on ultrasonography and hypointense on CT. On contrast-enhanced CT, there is decreased enhancement of the mass in the arterial phase and delayed enhancement in the late phase.64,66 A small, hypodense rim is often identified around the lesion—the so-called “halo sign.” On MRI, the pancreas is diffusely hypointense on T1- and slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The main pancreatic duct is usually narrow, and upstream dilatation of the pancreatic duct should raise concern for a pancreatic carcinoma. Both the bile duct and the pancreatic duct may be narrowed (double duct sign), a feature that is otherwise suggestive of pancreatic carcinoma.

An irregularly narrowed main pancreatic duct is very characteristic of AIP (Fig. 39.11). On ERCP, the following four features help distinguish AIP from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: (1) a long stricture involving more than one third of the main pancreatic duct, (2) lack of upstream dilatation, (3) side branches arising from a strictured segment, and (4) the presence of multiple strictures involving the main pancreatic duct.67 The presence of all four features is highly specific but only moderately sensitive for AIP.67 Although the Japanese and Korean criteria for diagnosis of AIP are highly dependent on pancreatography, those published from the United States do not require imaging of the pancreatic duct.68–70

Within 1 to 2 weeks of initiation of steroid therapy, there is a dramatic shrinkage of the mass with partial to complete normalization of the main pancreatic duct. In the late phase of this disease, the pancreas appears shrunken and atrophic.

Pathogenesis

Although one of the defining features of AIP is an elevated level of serum and tissue IgG4, it is unlikely that this antibody is the primary driver behind the tissue destruction seen in this disease.36 In fact, there is evidence to suggest that IgG4 may play an antiinflammatory role. Nonetheless, the IgG4 antibody has some unusual structural and functional properties. It is the least common of the four IgG subclasses, accounting for less than 5% of the total IgG in healthy persons. The molecule binds only weakly to C1q and Fcγ receptors, and therefore is believed not to activate the classic complement pathway.71 An even more unique aspect of the IgG4 molecule is the half-antibody exchange reaction. The bond between the disulfide chains is weak, resulting in a dissociation of the heavy chains, and this allows for the chains to randomly combine, resulting in asymmetric antibodies with two different antigen combining sites, accounting for the inability to form immune complexes.36,71

Etiology: Potential Initiating Mechanisms

It is likely that multiple factors can trigger the development of AIP.

Genetic Factors.

The genetic susceptibility factors that have been identified in the Japanese population include the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) serotypes DRB1*0405 and DQB1*0401.72

Bacterial Infection.

Homology has been demonstrated between the plasminogen-binding protein of Helicobacter pylori and the ubiquitin-protein ligase E3 component n-recognin, a protein expressed in pancreatic acinar cells,63 raising the possibility that a protein mimicry may incite the production of autoantibodies. The same study identified a unique antibody in the serum of patients with AIP: anti–plasminogen binding protein.63

Pathogenesis: Immunologic Alterations in Autoimmune Pancreatitis

Regardless of the trigger, the immunologic response, at least in the type 1 variant, appears to be fairly uniform, dominated by a type 2 helper T-lymphocyte (Th2) immune response. Evidence for this comes from studies that have shown substantially higher messenger RNA levels for IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13. The peripheral T lymphocytes are also shifted to a Th2 response.73,74 Another characteristic of this disease is the increased numbers of regulatory T cells.74 Transforming growth factor-β also appears to be overexpressed and may in part explain the fibrosis.

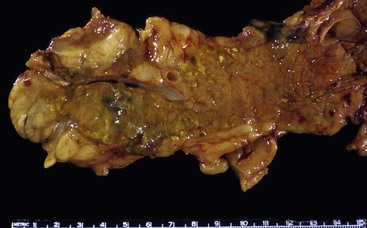

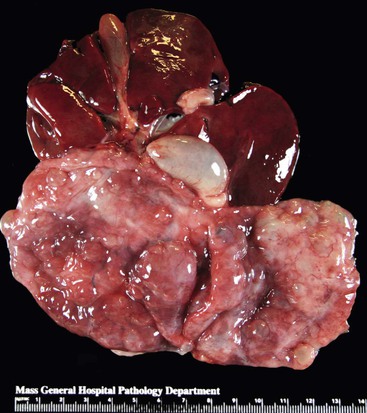

Pathologic Features

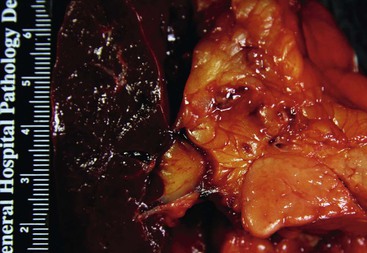

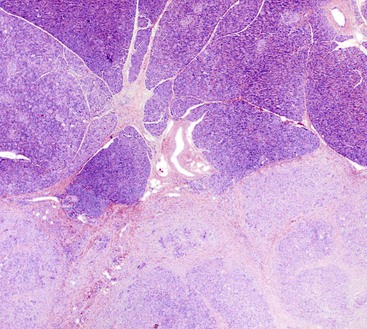

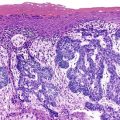

The disease can involve any part of the pancreas. In the active phase, the pancreas is enlarged, but in the late phases of the disease, the pancreas may appear shrunken and fibrotic. On gross evaluation, the pancreas is generally bulky and feels firm to hard, although serial sections usually fail to identify a distinct tumor (Fig. 39.12). Occasionally, a distinct mass is identified, in which case the gross appearance is indistinguishable from a pancreatic neoplasm (Fig. 39.13). The main pancreatic duct is typically narrow, and dilatation of the main pancreatic duct is uncommon. Stigmata of alcoholic pancreatitis, such as pseudocysts and calcification, are uncommon as well, although their presence does not exclude the diagnosis of AIP.

Although the principal changes in both variants of the disease are fibrosis and inflammation, the pattern of fibrosis and the type and degree of inflammation are so markedly different that they are discussed separately here.

Type 1 Autoimmune Pancreatitis

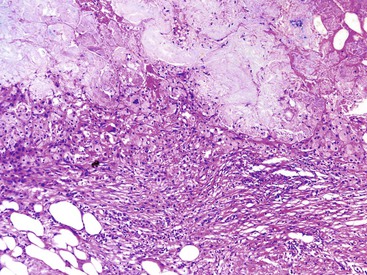

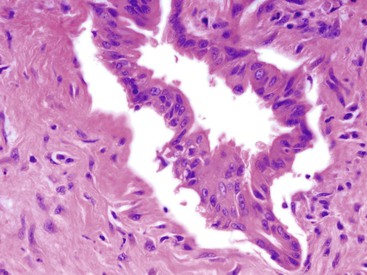

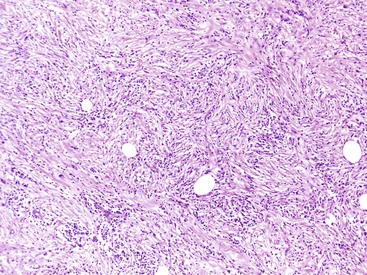

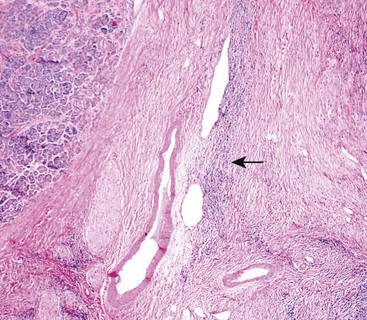

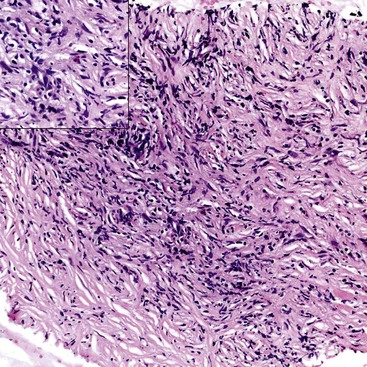

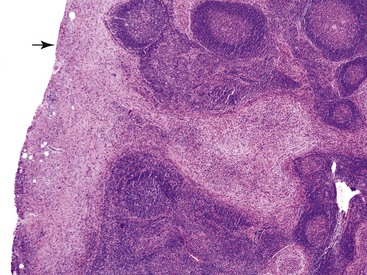

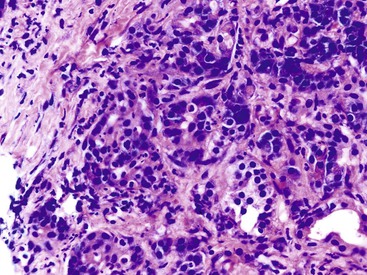

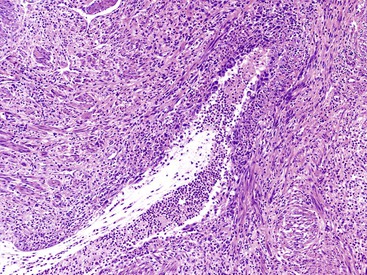

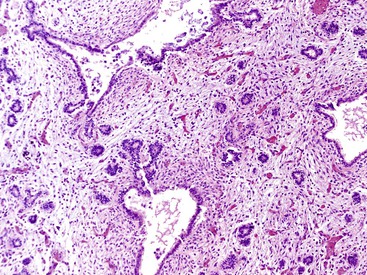

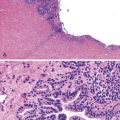

Histologically, the type 1 variant of AIP is a prototypical IgG4-related disease that is characterized by a triumvirate of histologic features: dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, storiform-type fibrosis (Fig. 39.14), and obliterative phlebitis (Fig. 39.15).17,39,43,44,46,48,53,75–78

Although in some areas the fibrosis is organized in a patternless pattern, a careful evaluation invariably reveals storiform-type fibrosis (Fig. 39.16). The fibroinflammatory infiltrate also extends into the peripancreatic adipose tissue and the intrapancreatic portion of the bile duct (Fig. 39.17), and careful evaluation of these lesions reveals a substantial population of spindle-shaped cells. These cells, representing either fibroblasts or myofibroblasts, are an important component of this disease and contribute in no small measure to the storiform pattern that is characteristic of this lesion.

The disease is characterized by a dense and diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and an absence of IgG4+ plasma cells is incompatible with a diagnosis of AIP. Eosinophils are identified in virtually every case, with occasional cases showing a marked infiltrate, sufficient to raise the possibility of “eosinophilic pancreatitis.”

Obliterative phlebitis is readily identified, but the vein may be camouflaged by the dense and diffuse inflammatory infiltrate. It is often difficult to identify totally obliterated veins, and an elastic stain may help to uncover these venous channels. However, an elastic stain is not mandatory: medium-sized venous channels are usually accompanied by arteries, which are less likely to be affected by the inflammatory process and can therefore serve as guideposts for identification of the veins. A less widely acknowledged feature of type 1 AIP is obliterative arteritis. As in obliterative phlebitis, the lumen and the wall of the vascular channel are infiltrated by lymphocytes and plasma cells. The presence of necrotizing inflammation involving either the vein or the arteries excludes the diagnosis of AIP.

The ductal epithelium is typically preserved, although occasionally intraepithelial lymphocytes are found. Notably, the ducts are not associated with neutrophils, and erosion and ulceration of the duct-lining epithelium are distinctly uncommon. Although the inflammatory cells tend to aggregate around ducts, this periductal infiltrate is seldom as prominent as in the type 2 variant of the disease.

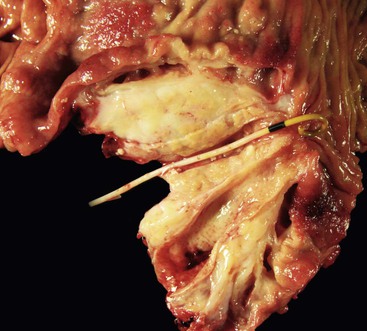

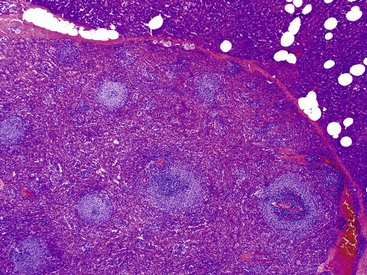

The regional lymph nodes show a marked increase in IgG4+ plasma cells and may occasionally demonstrate fibrosis of the capsule (Fig. 39.18). Long-standing examples of AIP exhibit extensive atrophy of the exocrine component, although the endocrine component is usually preserved, at least in the initial phases of the disease.

After steroid therapy, there is a rapid depletion of the inflammatory component, leaving behind only a sparse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and IgG4-bearing plasma cells typically are not identified. Such cases do not fulfil the minimum diagnostic criteria for AIP. Nonetheless, a storiform pattern of fibrosis may be recognizable and may provide the only clue to the existence of AIP in the specimen.

Type 2 Autoimmune Pancreatitis

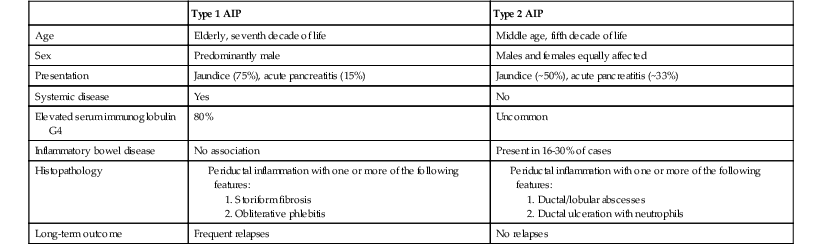

Histologically, type 2 AIP has little in common with the type 1 variant; instead, the morphologic features overlap with other forms of chronic pancreatitis (Table 39.2).

Table 39.2

Differences between Type 1 and Type 2 Autoimmune Pancreatitis (AIP)

| Type 1 AIP | Type 2 AIP | |

| Age | Elderly, seventh decade of life | Middle age, fifth decade of life |

| Sex | Predominantly male | Males and females equally affected |

| Presentation | Jaundice (75%), acute pancreatitis (15%) | Jaundice (~50%), acute pancreatitis (~33%) |

| Systemic disease | Yes | No |

| Elevated serum immunoglobulin G4 | 80% | Uncommon |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | No association | Present in 16-30% of cases |

| Histopathology |

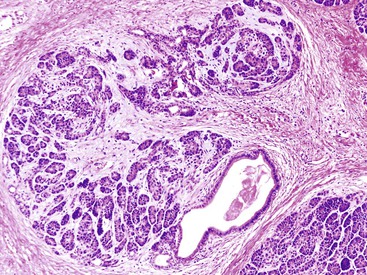

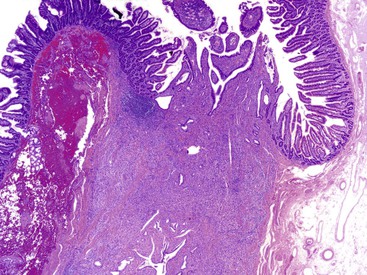

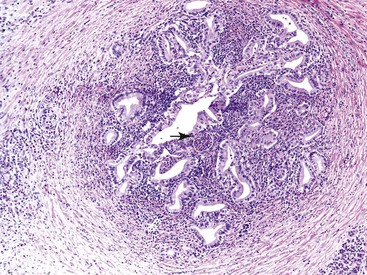

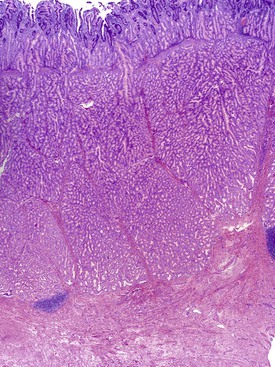

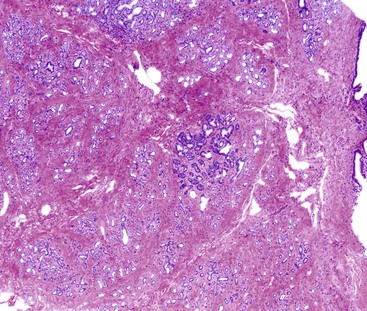

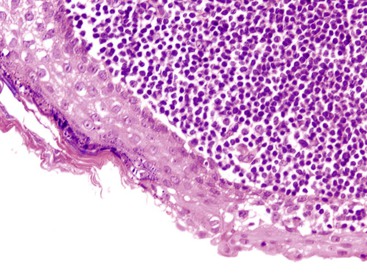

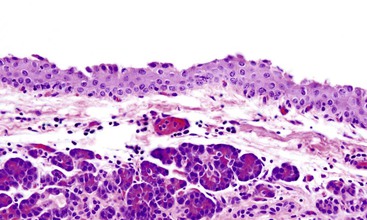

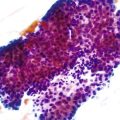

The most distinctive feature of this variant is a dense periductal collar of lymphocytes and plasma cells, accompanied by neutrophilic microabscesses within the lumen of the duct: the so-called granulocytic epithelial lesion (Fig. 39.19).17,39,43,44,46,48,53,78 Erosion and ulceration of the duct lining are frequently seen, occasionally accompanied by complete destruction of the duct. Another characteristic feature of this variant is the presence of neutrophils within acinar units (Fig. 39.20). Storiform-type fibrosis is typically not prominent. Although some veins may be focally involved by the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (i.e., phlebitis), overt obliterative phlebitis is uncommon.

Unclassified Autoimmune Pancreatitis

Not all cases of AIP fit into the aforementioned subtypes. Some cases demonstrate the histologic triumvirate of type 1 disease (i.e., dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, storiform-type fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis) but in addition show more than an occasional intraductal aggregate of neutrophils. Others show typical type 2 disease but with diffuse infiltrates of IgG4+ plasma cells, more than 50/HPF. For now, it is prudent not to subcategorize such cases but instead to label them as unclassified variants of AIP, because the therapy (corticosteroids) is similar for both forms of the disease.

Immunohistochemistry

Both variants of AIP show an admixture of B and T cells, although the T cells tend to dominate. The B cells are typically organized as lymphoid aggregates. By definition, both the lymphocyte and the plasma cell populations are polyclonal.

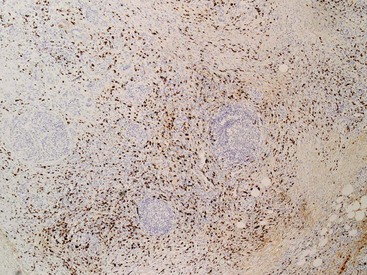

Virtually every case of type 1 AIP shows a markedly elevated number of IgG4+ plasma cells (Fig. 39.21)43,46,48,79 with a minimum requirement of 50 IgG4+ plasma cells per high-power field on a resection specimen and 10/HPF on a biopsy sample.51,80 Typically, the IgG4+ plasma cells are diffusely distributed, although focal accentuations around venous channels and ducts may be appreciable.

In contrast, an elevated number of IgG4+ plasma cells is not required for a diagnosis of type 2 AIP.43,46,48 Nonetheless, occasional pockets of IgG4-bearing plasma cells may be identified in this form of the disease (Fig. 39.22), and they also may be seen in other forms of pancreatitis.

A recent consensus document on IgG4-related disease emphasized the importance of the ratio of IgG4 to total IgG, with a ratio of greater than 40% strongly supporting the diagnosis of AIP.80

Differential Diagnosis

Autoimmune Pancreatitis versus Pancreatic Carcinoma

In its most common manifestation, AIP mimics pancreatic cancer; therefore, a correct diagnosis of AIP can prevent the patient undergoing major surgery. Two factors make this an extremely challenging diagnosis: (1) The incidence of AIP is far lower than that of pancreatic cancer, and (2) there is no single diagnostic clinical feature or test that can identify the full spectrum of AIP. The most feared scenario is misdiagnosis of AIP in a patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, because any delay in diagnosis may close the already narrow therapeutic window for surgery in such patients.

Usually, the diagnosis of AIP (particularly type 1) is established on clinical and radiologic grounds alone, and a biopsy is performed only in a minority of cases. For the surgical pathologist, the distinction is fairly easy. Although the ducts involved by AIP may show mild reactive atypia, they are unlikely to be mistaken for an adenocarcinoma. On FNA biopsy, however, these “atypical” ducts may be mistaken for adenocarcinoma.81 A substantial minority of biopsy specimens from patients with AIP are nondiagnostic because they lack the key histologic features, probably because the involvement of the pancreas is patchy (Fig. 39.23). A minority of pancreatic adenocarcinomas show a dense intratumoral and peritumoral lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate that is also rich in IgG4-bearing plasma cells43; because the number of IgG4+ plasma cells may be elevated, these lesions may be mistaken for AIP. To avoid this diagnostic trap, an elevated number of IgG4+ plasma cells should not be used as the sole criterion to diagnose AIP, the diagnosis requires careful correlation with clinical, radiologic, and serologic features.

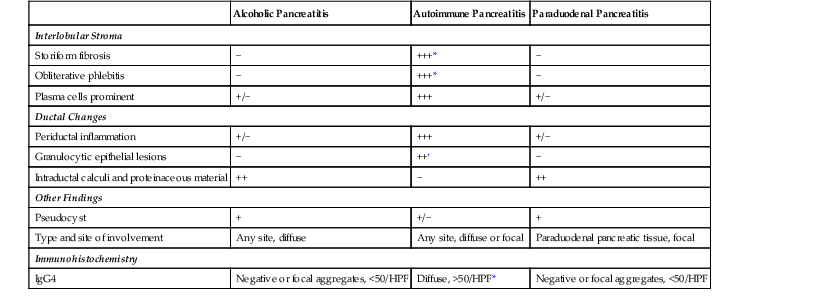

Autoimmune Pancreatitis versus Other Forms of Chronic Pancreatitis

Histologically, type 1 AIP is unlikely to be mistaken for any other form of pancreatitis. However, the histologic features of type 2 AIP may overlap with those of chronic alcoholic pancreatitis (Table 39.3). Alcohol-related pancreatitis is typified by the presence of dense acellular fibrosis, calcification, and dilated ducts filled with inspissated proteinaceous material; these features are uncommon in the type 2 variant. Furthermore, alcoholic chronic pancreatitis shows only a mild inflammatory infiltrate, composed predominantly of lymphocytes. Nonetheless, in our experience, some pancreata from patients with alcohol abuse show a periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate associated with intraepithelial neutrophils.

Table 39.3

Histologic Differences among the Three Common Forms of Pancreatitis

| Alcoholic Pancreatitis | Autoimmune Pancreatitis | Paraduodenal Pancreatitis | |

| Interlobular Stroma | |||

| Storiform fibrosis | − | +++* | − |

| Obliterative phlebitis | − | +++* | − |

| Plasma cells prominent | +/− | +++ | +/− |

| Ductal Changes | |||

| Periductal inflammation | +/− | +++ | +/− |

| Granulocytic epithelial lesions | − | ++† | − |

| Intraductal calculi and proteinaceous material | ++ | − | ++ |

| Other Findings | |||

| Pseudocyst | + | +/− | + |

| Type and site of involvement | Any site, diffuse | Any site, diffuse or focal | Paraduodenal pancreatic tissue, focal |

| Immunohistochemistry | |||

| IgG4 | Negative or focal aggregates, <50/HPF | Diffuse, >50/HPF* | Negative or focal aggregates, <50/HPF |

* Seen only in type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis.

† Seen only in type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis.

HPF, High-power field; IgG4, immunoglobulin G4; +++, virtually always present; ++, frequently present; +, present in a minority of cases.

Other Diseases That May Mimic Autoimmune Pancreatitis

Additional diseases that should be ruled out include lymphoma, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, infectious diseases, and other inflammatory diseases such as granulomatosis and polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis).80 The morphologic features of AIP do not overlap with these diseases. However, several of these diseases may be associated with elevated numbers of IgG4-bearing plasma cells.82–84

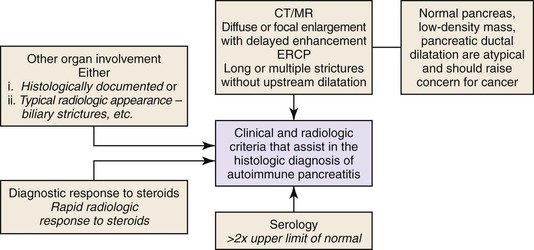

Diagnostic Criteria

Histology is the gold standard for the diagnosis of AIP, but this statement applies primarily to a resection specimen. On biopsy material, a diagnosis of AIP should not be rendered in a clinical vacuum: Close collaboration among clinician, radiologist, and pathologist is vital. A recently published international consensus document on the diagnostic criteria of AIP has codified this collaborative effort.77 A modified version of this algorithm is shown in Figure 39.24.

Diagnostic Value of an Ampullary or Bile Duct Biopsy

A random biopsy specimen from either the ampulla of Vater or the bile duct may provide diagnostically valuable information. In one study, a cutoff value of 10 IgG4+ plasma cells per HPF was used; the sensitivity and specificity were 52% and 89%, respectively, for ampullary biopsy and 52% and 96% for bile duct biopsy.85 The results of other studies have been similar, although they have reported higher specificity and sensitivity values.86,87

Although the presence of more than 10 IgG4-bearing plasma cells per HPF provides another tool for distinguishing AIP from pancreatic carcinoma, several caveats should be considered when interpreting these results:

Therapy

Although there is little in terms of specific therapy to offer patients with most forms of chronic pancreatitis, AIP responds dramatically to immunosuppressive therapy. Moreover, some patients with AIP show spontaneous improvement. A dramatic response to steroids provides additional reassurance of a benign disease.

In the United States, most physicians withdraw steroids at the end of 3 months. Investigators from Japan, however, maintain patients on low-dose steroid therapy to prevent relapses. Emerging data support the use of rituximab in treating relapses.40

Risk of Malignancy

The development of synchronous and metachronous pancreatic adenocarcinomas in patients with AIP has been described.88–90 We identified two cases of metachronous pancreatic carcinoma in our cohort of patients with AIP.91 Almost all of these malignancies have arisen on a background of type 1 AIP. Recent data have shown that pancreata from patients with AIP, compared with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, have at least an equivalent number of PanIN lesions, as well as a comparable number of high-grade PanIN lesions (grade 2 and 3).91 These findings, although far from conclusive, do raise the possibility that patients with AIP may have an elevated risk of malignancy, and the level of this risk may equal that in patients with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis.

Paraduodenal Pancreatitis (“Groove” Pancreatitis)

Definitions and Terminology

Paraduodenal pancreatitis is a distinct form of chronic pancreatitis that involves paraduodenal pancreatic tissue—the duodenum itself—and is invariably centered on the minor papilla.92 A multitude of other terms have been used to describe this entity, including cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas,93 pancreatic hamartoma of duodenal wall,94 periampullary or periduodenal wall cyst,95 adenomyoma/myoadenomatosis, and96 “groove” pancreatitis.97 Each of these terms describes only one facet of this multifaceted disease. The designation groove pancreatitis is based on the fact that the pancreatitis is located in the groove between the common bile duct and duodenum. Paraduodenal pancreatitis has been proposed as a unifying term for this entity.92

Clinical Features

This disease manifests most commonly in the fourth decade of life and predominantly affects males.17,92,98,99 Most patients have a history of alcohol abuse and often a history of smoking. The most common clinical symptoms are abdominal pain, vomiting, and weight loss.99 Similar to AIP, paraduodenal pancreatitis often forms a tumefactive lesion in the head of the pancreas and thus mimics pancreatic carcinoma. A subset of patients have symptoms related to upper gastrointestinal obstruction, a consequence of duodenal stenosis. The disease can also narrow the common bile duct, resulting in obstructive jaundice.

Radiologic Features

Radiologically, the disease may be limited to the duodenal wall or may extend to both the duodenum and the adjacent pancreas. On CT, a poorly enhancing, hypodense lesion is often identified in the groove between the common bile duct and the duodenum.98 The duodenal wall is invariably thickened, and cysts are commonly found within and adjacent to the duodenal wall.99,100 Luminal narrowing of the distal common bile duct and the main pancreatic duct may be seen. However, an abrupt pancreatic and bile duct cutoff, as seen in pancreatic carcinoma, is not a feature of paraduodenal pancreatitis. Radiologically, this disease may be mistaken for a host of neoplastic entities, including solid pancreatic neoplasms such as pancreatic and duodenal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor, and cystic pancreatic neoplasms including intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.101

Pathogenesis

The etiology of this disease is uncertain, although data obtained from the histologic evaluation of resected specimens permits us to speculate about the etiopathogenesis of paraduodenal pancreatitis.17,92 Any hypothesis must take into account two factors: (1) The disease is centered on the accessory pancreatic duct, and (2) there is a strong association with alcohol abuse. There is also evidence to suggest that some types of mass-forming pancreatitis are associated with pancreatic divisum. Therefore, one could speculate that a partially obstructed accessory pancreatic duct precipitates paraduodenal pancreatitis in an individual who is susceptible to alcoholic pancreatitis.

Pathologic Findings

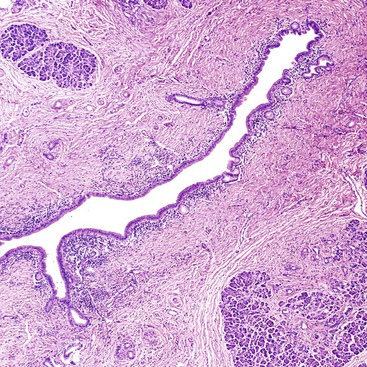

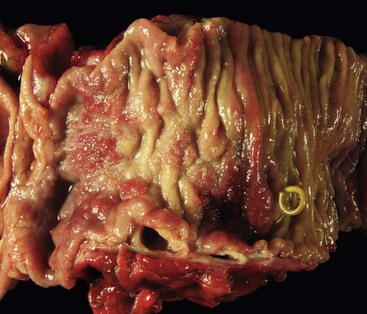

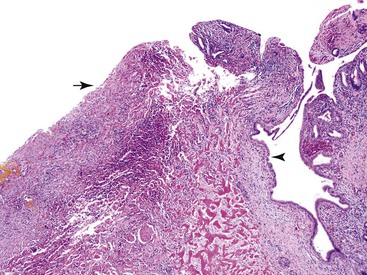

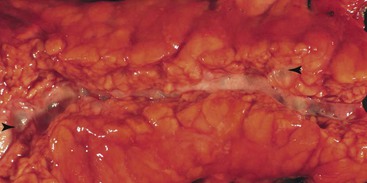

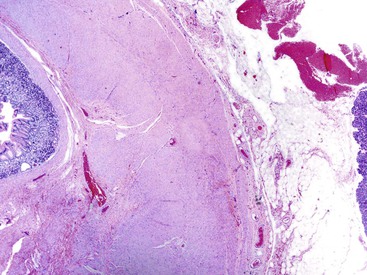

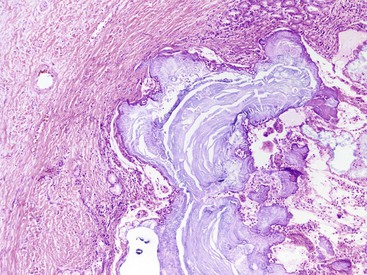

The gross evaluation of the pancreaticoduodenectomy specimen plays a critical role in establishing a diagnosis of paraduodenal pancreatitis.17,92 The disease is centered either in the duodenal wall or at the interface between the duodenum and the pancreas. It is also vital to document the involvement of the minor papilla. The minor papilla is identified approximately 2 cm proximal to the major papilla. The duodenal wall is thickened, and the mucosal surface appears granular (Fig. 39.25).93 The lobular architecture of the paraduodenal pancreas is replaced by a gray-white fibrotic lesion (Fig. 39.26). The diseased tissue is invariably associated with cysts that contain clear fluid.93 Cysts as large as 10 cm in diameter have been described. Although the lesion is often centered on the accessory pancreatic duct, it is frequently difficult to identify the duct grossly. The scarring process can narrow both the duodenum and the distal common bile duct.

Histologically, no single feature is diagnostic of this disease. However, a constellation of features, when viewed collectively, support a diagnosis of paraduodenal pancreatitis.17,92,93,98

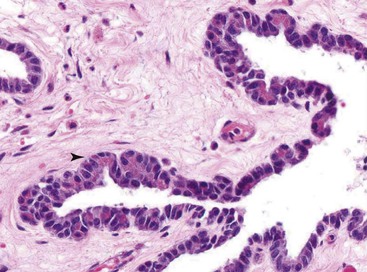

2. Multiple cysts are identified within the zones of fibrosis (Figs. 39.27 and 39.28). Some of these cysts are lined by ductal epithelium, although much of the epithelium is eroded. The larger cysts are lined by granulation tissue and may contain proteinaceous material.

4. Most cases demonstrate a rather dramatic Brunner gland hyperplasia (Fig. 39.29).

Differential Diagnosis

Although the radiologic features of paraduodenal pancreatitis may mimic carcinoma, histologic evaluation readily excludes ampullary or duodenal adenocarcinoma. However, a relatively small periampullary carcinoma may be associated with a paraduodenal pancreatitis–like lesion. Therefore, a thorough evaluation to exclude the possibility of a carcinoma is necessary.

Therapy

Conservative therapeutic options include alcohol abstinence and smoking cessation. However, it has been argued that surgery is the treatment of choice in symptomatic patients.102

Eosinophilic Pancreatitis

Eosinophilic pancreatitis, in which the inflammatory infiltrate is predominantly or exclusively composed of eosinophils, is an extraordinarily rare condition.37 A more common cause of pancreatic tissue eosinophilia is AIP.41,42,48,80 Most cases of eosinophilic pancreatitis were reported before the recognition of AIP, and in retrospect, it is likely that some of these cases in the literature represent examples of AIP with prominent eosinophilia.

Clinical Features

The presenting symptoms vary from abdominal pain to obstructive jaundice.37,103,104 Some patients show peripheral eosinophilia. A prior history of allergic symptoms is not uncommon. Imaging reveals a pancreatic mass in most cases and may demonstrate stricture of the bile duct.105 Pseudocyst formation is occasionally seen.2 Hypereosinophilic syndrome develops in some of these patients.37,106

Pathologic Findings

Grossly, the pancreas may be enlarged and fibrotic. Histologically, a diffuse eosinophilic infiltrate is seen around ducts, acini, and interlobular septa.107 In addition, eosinophilic phlebitis and arteritis may be seen.37 Although lymphocytes and plasma cells are also present, they do not dominate the picture. In addition to this diffuse form of involvement, focal involvement of the pancreas, particularly adjacent to a pseudocyst, has been reported.37 The eosinophilia can also involve the gastrointestinal tract, particularly the duodenum. Involvement of the biliary tract in the form of multiple biliary strictures has also been reported.37

Differential Diagnosis

A diverse group of diseases is associated with increased numbers of eosinophils in the pancreas, including AIP, malignancy, parasitic infections, hypersensitivity reaction to drugs, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, and systemic mastocytosis.37 As mentioned previously, the most common concern in the differential diagnosis of eosinophilic pancreatitis is AIP. Findings of elevated levels of serum IgG4, multiorgan tumefactive lesions, the presence of storiform fibrosis, and elevated numbers of IgG4+ plasma cells favor of a diagnosis of AIP. The mainline therapy for both diseases is steroids.

Tropical Pancreatitis

Tropical pancreatitis is a variant of chronic pancreatitis that is seen in tropical regions such as the Indian subcontinent and certain parts of Africa.108,109 It is also been referred to as “Afro-Asian pancreatitis,” “juvenile pancreatitis syndrome,” “chronic calcific pancreatitis of the tropics,” “nonalcoholic tropical pancreatitis, ” and “nutritional pancreatitis.” In southern India, where the disease is endemic, the prevalence is 126 cases per 100,000 persons.109

Tropical pancreatitis occurs predominantly in children and young adults and is characterized by pain, pancreatic calcification, and diabetes. Older patients with tropical pancreatitis have also been reported. The disease affects both men and women.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Historically, suspected causative factors for tropical pancreatitis have included malnutrition and cyanogenic glycosides from consumption of cassava.109 Mutations and polymorphisms in SPINK1, CFTR, and cathepsin B (CTSB) appear to increase the susceptibility to this disease.26,110,111 It is likely that the disease involves an interplay between genetic and environmental factors, and the genes implicated are likely to be disease modifiers rather than the direct cause of tropical pancreatitis.26,110,111

Similar to other forms of pancreatitis, tropical pancreatitis is associated with an increased risk of malignancy—a fivefold increase.112

Pathologic Features

The pathologic features depend on the duration and severity of disease. At an advanced stage, the pancreas appears shrunken. The most characteristic feature of tropical pancreatitis is the presence of large intraductal calculi in the main duct. Histologically, there appears to be little difference between tropical pancreatitis and alcoholic pancreatitis. The disease shows both intralobular and interlobular fibrosis and a sparse inflammatory infiltrate. It is distinguishable from alcoholic chronic pancreatitis by a younger patient age at presentation and by the presence of large intraductal calculi.

Obstructive Pancreatitis

A variety of neoplastic and non-neoplastic diseases are associated with obstruction of large-caliber pancreatic ducts. There is extensive loss of acinar tissue distal to the obstruction, although the islets are preserved. Eventually, extensive interlobular and intralobular fibrosis are observed (Fig. 39.30).

Infectious Causes of Pancreatitis

Tuberculous Pancreatitis

Clinical Features

Similar to other infectious diseases of the pancreas, tuberculosis of the pancreas is uncommon. The disease primarily involves peripancreatic lymph nodes but may extend into the pancreatic parenchyma.113

The disease commonly manifests as a mass in the head of the pancreas, mimicking carcinoma.113 Other forms of presentation include obstructive jaundice, pancreatic abscess, and acute and chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatic tuberculosis should be considered in patients who have lived in or travelled to areas that are endemic for tuberculosis. In most cases, the disease is present in other organs; primary pancreatic tuberculosis is exceptionally rare.

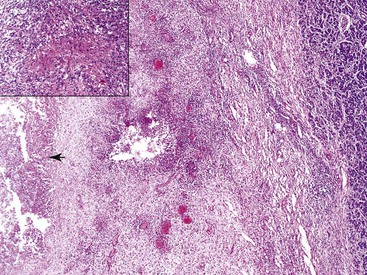

Pathologic Findings

Intrapancreatic tuberculosis manifests as a tumefactive mass that may be focally cystic (Fig. 39.31). A surgical biopsy or FNA of peripancreatic lymph nodes or the pancreas itself reveals necrotizing granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 39.32). Documentation of the presence of acid-fast bacilli, positive culture, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of mycobacterial infection. Other causes of granulomatous inflammation in the pancreas include sarcoidosis (a disease that may also present as a tumefactive lesion),114 Crohn’s disease, and type 2 AIP.43

Other Infections

Infection as a cause of pancreatic disease is extremely uncommon in immunocompetent hosts but may be seen in immunocompromised individuals.

A wide variety of infectious pathogens can affect the pancreas, including viruses, parasites, bacteria, and fungi. Among the more common forms of infectious pancreatitis are caused by Ascaris lumbricoides,115 cytomegalovirus,116 and Strongyloides stercoralis.117 A. lumbricoides may enter the pancreas via the pancreatic duct system and cause necrosis, abscess formation, granulomatous inflammation, and fibrosis.

Solid Non-neoplastic Lesions That Mimic Pancreatic Neoplasms

Intrapancreatic Accessory Spleen

An accessory spleen is identified in approximately 10% of the population. The majority of these are located at the splenic hilum. The pancreas happens to be the second most frequent location, with 20% located in the tail of the pancreas.118 This developmental abnormality is asymptomatic but has received attention because of the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging. An intrapancreatic accessory spleen may be associated with an intrasplenic epidermoid cyst.

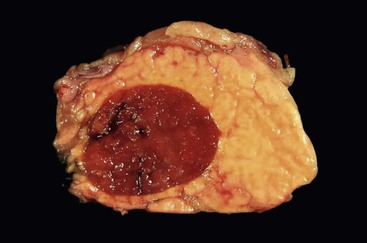

Pathologic Features

Grossly, these are well circumscribed, solid lesions with color and texture identical to spleen—a firm, beefy-red nodule (Fig. 39.33). A unilocular cystic lesion may be identified within the splenic tissue.119,120

The contrast enhancement pattern on CT and the signal intensities on MRI are similar to those of the normal spleen.119,120 Preoperative diagnosis of an intrapancreatic spleen is often possible based on imaging and FNA biopsy.121

Histologically, these lesions are identical to the native spleen, composed of white pulp and red pulp (Fig. 39.34). An epidermoid cyst lined by squamous epithelium may be identified.

Lipomatous Pseudohypertrophy

Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy is associated with a marked increase in intrapancreatic mature adipose tissue.122–124 By definition, this diagnosis excludes other pathologies associated with a significant increase in intrapancreatic fat, such as morbid obesity, diabetes mellitus, and chronic pancreatitis. This entity is extremely uncommon, yet noteworthy because it may mimic a malignant process.

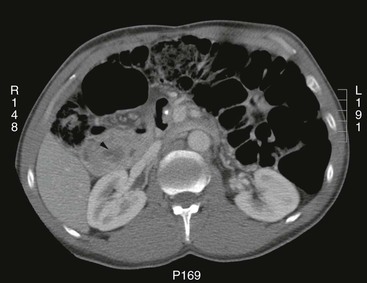

Clinical Features

The mean patient age at presentation is 41 years, and the disease affects both women and men without a distinct difference in sex distribution.122 The presenting symptoms are variable, and a significant percentage of patients are identified on cross-sectional imaging performed for symptoms unrelated to the pancreas (Fig. 39.35). However, patients may also have symptoms related to a mass lesion, such as abdominal pain and biliary obstruction. Cross-sectional imaging reveals an intrapancreatic fatty neoplasm. Approximately two thirds of the cases show diffuse involvement of the pancreas, and the remaining one third demonstrate a focal intrapancreatic fatty mass. These tumefactive lesions are typically large, and lesions as large as 24 cm have been recorded.122 Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy has been associated with Shwartzman-Diamond syndrome, Bannayan syndrome, Johnson-Blizzard syndrome, and juvenile variant of Parkinson disease.

Pathogenesis

Little is known about the pathogenesis of this lesion. One plausible hypothesis is that it represents an extremely infiltrative lipoma, although some authors have argued persuasively against this possibility.122 Before a diagnosis of lipomatous pseudohypertrophy is considered, a well-differentiated liposarcoma should be excluded. Well-differentiated liposarcomas are located mainly in the retroperitoneal region and typically do not manifest as a primary pancreatic mass. Microscopically, large, atypical stromal cells are seen within fibrous septa. Nonetheless, on a FNA or core biopsy specimen, it may not be possible to unequivocally distinguish lipomatous pseudohypertrophy from a lipoma-like well-differentiated liposarcoma. Immunohistochemistry for MDM2 is extremely helpful in such cases; in well-differentiated liposarcomas the atypical stromal cells show nuclear reactivity for MDM2.

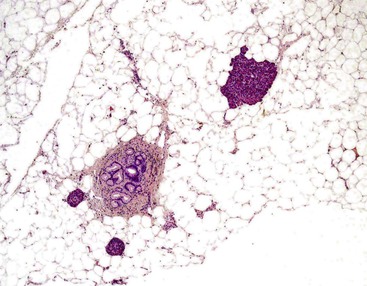

Pathologic Features

In cases with diffuse involvement, a massive increase in adipose tissue is identified throughout the pancreas. In individuals with focal involvement, a sharp demarcation between the fatty deposition and adjacent pancreas is present. The lesion may compress the common bile duct.

The tumefactive lesion is composed almost entirely of mature adipose tissue, within which scattered pancreatic elements are identified (Fig. 39.36). Apart from the “dilution” of the pancreatic parenchyma by adipose tissue, the pancreas itself is histologically unremarkable and significantly does not show evidence of either acute or chronic pancreatitis.

Therapy

Asymptomatic cases may be managed conservatively, without resection, provided a secure diagnosis can be established. Resection is required in symptomatic patients.

Pancreatic Hamartoma

A variety of terms have been used to designate this entity, including multicystic pancreatic hamartoma, solid pancreatic hamartoma, and pancreatic solid and cystic hamartoma.94,125–128 Pancreatic hamartoma is histologically characterized by a disorganized proliferation of acinar, endocrine, and ductal cells.125,128,129 These lesions have been identified in both neonates and adults and have ranged in size from 1 cm to 11.5 cm.

Pathologic Features

Grossly, these lesions vary from homogenous white, solid nodules to solid and cystic lesions (Fig. 39.37).125,128,129,129a The lesion is composed of mature pancreatic tissue (predominantly mature ducts and acini), albeit disorganized, thus fulfilling the definition of a hamartoma. The ductal structures may show significant dilatation and cystification (Fig. 39.38). Neither acinar nor ductal elements show atypia. While scattered endocrine cells are detected, well-formed islets are absent. A paucity of nerve twigs has also been observed.

Before arriving at a diagnosis of pancreatic hamartoma, other forms of pancreatitis, including AIP, should be excluded. Similar to chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic hamartomas are associated with increased amount of pancreatic stroma. The mesenchymal cells within this stroma are positive for CD34 and CD117, the latter reactivity is generally weak.127,129a

Adenomyomatous Hyperplasia of the Vaterian System

Adenomyomatous hyperplasia of the Vaterian system is a benign, non-neoplastic proliferation of glands and mesenchymal elements involving the distal portion of the bile duct and the ampullary region.130,131 A variety of synonyms have been used to describe this entity, including “adenomyoma,” “adenomyomatosis,” “myoepithelial hamartoma,” and “adenomyomatous hyperplasia.” The term adenomyomatous hyperplasia is preferable, because “adenomyoma” has a neoplastic connotation. This lesion is benign without malignant potential, and its importance lies in its ability to mimic an ampullary malignancy.

Clinical Features

This is a disease of adults. The mean patient age in one series was 63 years, with males and females affected equally.130 Patients typically have symptoms related to obstruction of the pancreaticobiliary tract, such as jaundice and abdominal pain. On endoscopy, an enlarged ampulla is identified; endosonographically, an ampullary lesion is typically present.

Pathologic Features

On macroscopic evaluation, a firm, nodular lesion is identified in the terminal portion of the bile duct and ampulla. The mucosa overlying the lesion is normal and lacks ulceration. Histologically, this lesion is characterized by lobules of small glands that often surround a larger duct (Fig. 39.39).130 The lobular pattern of organization helps distinguish this lesion from an invasive pancreaticobiliary carcinoma. The lobules are, in turn, surrounded by a robust mesenchymal proliferation composed of fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and scattered smooth muscle cells. Heterotopic pancreatic tissue may be identified adjacent to the lesion.

Non-neoplastic Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas

A variety of non-neoplastic pancreatic cysts mimic neoplastic cysts of the pancreas. Although the goal is to avoid resecting these cysts, in many instances such lesions cannot be distinguished from their neoplastic counterparts. Therefore, surgical pathologists occasionally encounter such cysts (Box 39.4).

Pseudocyst

A pseudocyst lacks a lining epithelium and contains amylase-rich fluid. Historically, pseudocysts were the most common cysts of the pancreas. More recently, with the increased detection of asymptomatic non-neoplastic and neoplastic pancreatic cysts, the relative percentage of pseudocysts has markedly declined. Nonetheless, they continue to constitute a great majority of cysts seen in clinical practice. Because they are seldom resected, the surgical pathologist is more likely to encounter a neoplastic pancreatic cyst than a pseudocyst. A pseudocyst can arise both within the pancreas and in peripancreatic tissue.

Clinical Features

Pseudocysts are a consequence of pancreatitis or trauma.16,18,132 The most common underlying trigger for pseudocysts is alcoholic pancreatitis, and pseudocysts are more common in young to middle-aged men than in women. Nonetheless, almost any form of acute or chronic pancreatitis can trigger the development of a pseudocyst.

Diagnosis of Pseudocyst

Endoscopic ultrasonography plays a major role in both diagnosis and treatment of pseudocysts. Imaging demonstrates a unilocular cyst filled with debris but without a mural nodule. Analysis of the cyst fluid demonstrates an elevated amylase level (by definition >250 IU/mL) and a low level of carcinoembryonic antigen (typically <200 IU/mL). The cytology specimen is typically hypocellular and usually shows a few inflammatory cells only.133 In addition, a large amount of acellular debris associated with blood pigment and hemosiderin is frequently seen.

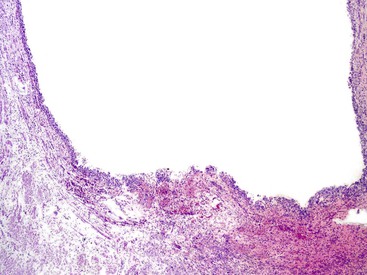

Pathologic Features

Pseudocysts are for the most part unilocular and contain turbid, sometimes blood-tinged fluid. These cysts can measure greater than 20 cm in size. The wall of the pseudocyst is typically thick and fibrotic (Fig. 39.40). By definition, the cyst lacks a lining epithelium.16–18,132 However, intrapancreatic pseudocysts frequently show large-caliber pancreatic ducts at the interface between the cyst and adjacent pancreas (Fig. 39.41). The epithelium lining the duct should not be misconstrued for cells lining the cyst. Instead, pseudocysts are lined by granulation tissue and fibrosis. If adjacent pancreatic tissue is present, stigmata of resolving acute pancreatitis or evidence of chronic pancreatitis may be seen.

Differential Diagnosis

When considering the diagnosis of a pseudocyst, it is prudent to histologically examine the entire cyst wall to rule out a cystic neoplasm. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms in which significant denudation of the lining epithelium may be seen include serous cystadenoma, mucinous cystic neoplasm, and, very occasionally, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Mucinous cystadenomas with total denudation of the lining epithelium will nonetheless show ovarian-type stroma, a feature not seen in a pseudocyst. Serous cystadenomas, particularly the unilocular variant, may exhibit complete loss of lining epithelium. However, this cystic neoplasm shows a unique subepithelial network of delicate capillary channels. Virtually all cases of pseudocysts are associated with a prior episode of acute pancreatitis, and in the absence of such a history, a diagnosis of a pseudocyst should be made with extreme caution.

Therapy

A significant percentage of pseudocysts resolve spontaneously; others progressively increase in size. The available treatment options include medical management, surgical treatment, and percutaneous or endoscopic drainage. The vast majority of pseudocysts are now treated endoscopically.

Lymphoepithelial Cyst of the Pancreas

Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas is a benign pancreatic cyst that is lined by squamous epithelium and surrounded by reactive lymphoid tissue.134,135