Inflammatory and Neoplastic Disorders of the Anal Canal

Thomas P. Plesec

Scott R. Owens

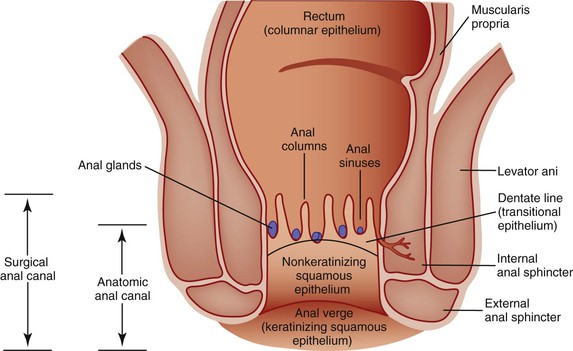

Embryology and Anatomy of the Anal Canal

The anal canal forms during the fourth to seventh weeks of gestation after partitioning of the cloacal membrane into ventral (urogenital membrane) and dorsal (anal membrane) portions.1 The epithelium of the superior two thirds of the primitive anal canal is derived from the endodermal hindgut; the inferior one third develops from the ectodermal proctodeum. The dentate line (i.e., pectinate line) is located at the inferior limit of the anal valves and delineates the fusion of these two epithelial derivatives. The dentate line also indicates the approximate former site of the anal membrane that ruptures in the eighth week of gestation. The outer layers of the wall of the anal canal are derived from the surrounding splanchnic mesenchyme.

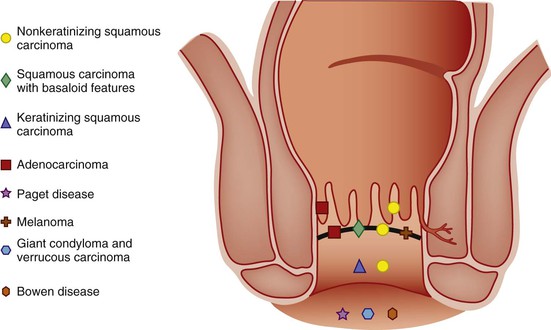

The anal canal, which is 3 to 4 cm long, is defined surgically by the borders of the internal anal sphincter (Fig. 32.1).2,3 The surgical anal canal begins at the apex of the anal sphincter complex. This palpable landmark (i.e., anal rectal ring) is located approximately 1 to 2 cm proximal to the dentate line. It ends where the nonkeratinizing squamous mucosa terminates at the perianal skin.4 The internal sphincter is the most distal portion of the internal circular layer of the muscularis propria and is continuous with the muscularis propria of the colorectum. The surface of the anal canal is lined by vertical mucosal folds called anal columns (i.e., columns of Morgagni), and it is separated by anal sinuses (i.e., sinuses of Morgagni). The columns connect at the most distal end by a horizontal row of mucosal folds known as the anal valves. Anal valves are typically most evident in children, but they may become more prominent with advancing age.

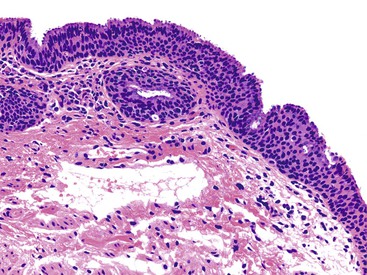

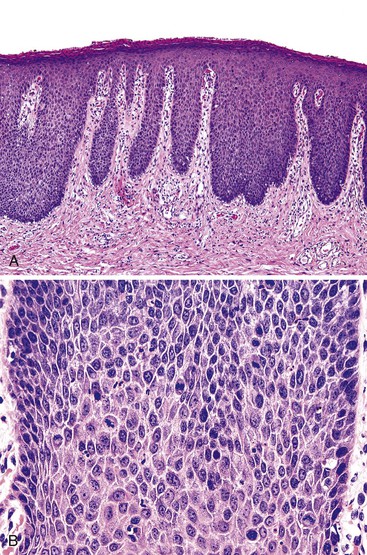

The location of the anal valves corresponds to the dentate line, which is located approximately at the midpoint of the surgically defined anal canal. The dentate line corresponds to the squamocolumnar junction. This is not an abrupt transition, but a transition zone that extends for several millimeters to slightly more than 1 cm. Microscopically, the epithelium lining the anal transition zone varies from a type that resembles the lower genitourinary tract to stratified squamous, columnar, or cuboidal tissue, often with islands of colorectal-type epithelium (Fig. 32.2).1 Despite its resemblance to bladder epithelium, the anal transition zone expresses cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK19 but not CK20.5,6 Immunohistochemical studies with human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45), an anti-melanoma monoclonal antibody, and S100 protein have demonstrated melanocytes in the anal transitional epithelium, although they are usually more prominent in the anal squamous zone.7

Microscopically, the mucosal lining superior to the transition zone is columnar, whereas the mucosa inferior to the transition zone is stratified squamous. The squamous mucous membrane is devoid of hair and other cutaneous appendages and does not keratinize. The anal canal ends at the anal verge, where the anal squamous mucosa merges with the true anal skin. At this point, hair follicles, sweat glands, and apocrine glands are detected.

The anal ducts are long, tubular structures that closely approach or penetrate the internal sphincter muscle and may undermine the rectal mucosa. These ducts are lined by transitional epithelium and mucus-producing cells, which are most common at the terminal portion of the ducts before their opening into the anal crypts. Nodules of lymphoid tissue are often seen surrounding these ducts. The epithelium lining the ducts shows a similar immunohistochemical profile to that of the overlying transitional mucosa (i.e., CK7 positive and CK20 negative).5,8

The dual embryologic origin of the anal canal results in a dual blood supply, venous and lymphatic drainage, and nerve supply.9–11 The superior two thirds of the anal canal is supplied by the superior rectal artery, a continuation of the inferior mesenteric artery. The venous drainage of the superior anal canal flows into the superior rectal veins, which are tributaries of the inferior mesenteric vein. The lymphatic drainage of the superior two thirds of the anal canal flows to the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes. The inferior one third of the anal canal is supplied primarily by the inferior rectal arteries, which are branches of the internal pudendal arteries. The venous drainage of this portion of the anal canal flows to the inferior rectal veins, which are tributaries of the internal pudendal veins, and ultimately to the internal iliac veins. Lymph drains into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. The nerve supply of the superior two thirds of the anal canal is part of the autonomic nervous system; the inferior third is supplied by the inferior rectal nerve through the sacral plexus.

These differences in embryology, blood supply, drainage, and innervation are clinically relevant, particularly when evaluating congenital malformations of the anal canal and predicting patterns of spread of neoplasms. In surgical pathology practice, it may be difficult to determine whether a tumor has arisen within the distal rectum, the anal canal, or the anal margin or perianal skin, because these anatomic zones overlap. Bulky tumors often obliterate the normal anatomy. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) suggests that a tumor is rectal in origin if its epicenter is located at least 2 cm proximal to the dentate line, whereas a tumor is considered to be an anal canal tumor if it is less than 2 cm from the dentate line.4 Identification of skin appendages helps to differentiate perianal skin carcinomas from true anal canal cancers. A perianal cancer is also defined by a tumor that is located within a 5 cm radius of the anus and that is completely visualized after gentle traction is placed on the buttocks. An anal canal tumor should not be completely visualized after gentle traction.

Embryologic Abnormalities of the Anus and Anal Canal

Clinical Features

Anorectal malformations occur in approximately 1 of 1500 to 5000 live births12,13 and affect both sexes equally. They range from minor anal anomalies to complex cloacal malformations. The most common congenital anomaly of the anus is anal atresia, which accounts for as many as 75% of all anorectal malformations.14 Anorectal agenesis accounts for approximately 10% of all anal atresias. As much as two thirds of congenital anal anomalies are associated with anomalies in other organ systems, most often the genitourinary system but also the central nervous system, skeleton, cardiovascular system, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract.14–16 Soon after birth, patients fail to pass meconium or have meconium that extrudes from a fistulous opening.17

Pathogenesis

Anorectal malformations have many causes, and genetic factors are considered an important component of their pathogenesis. Approximately 5% to 10% of malformations arise in children with a chromosomal abnormality, most commonly trisomy 21, and several monogenetic syndromes include anorectal malformations among their features.16 Anorectal malformations are more common in siblings of similarly affected patients.18 Ninety-five percent of patients with trisomy 21 and anorectal malformations have imperforate anus without a fistula, compared with only 5% of all patients with anorectal malformations. Congenital abnormalities, including anorectal malformations, have been associated with conception by using assisted reproduction methods.19

Pathology

Anorectal malformations are recognized by their gross anatomic features. The Wingspread classification of anorectal malformations is subdivided into high, intermediate, and low atresia based on the level of termination of the anorectum in relation to the levator ani muscle.20,21 This classification has proved quite useful because it shows good correlation with the type of surgical approach needed for repair.22 Fistula formation is a common finding in anorectal malformations, particularly in high and intermediate forms of anal atresia, and it may be rectovesical, rectoprostatic, rectourethral, or anocutaneous in boys and rectovaginal or anoperineal in girls.

An updated classification of anorectal malformations, the Krickenbeck scheme (Table 32.1), emphasizes the type of fistula associated with the malformation. The type of fistula helps to determine the location of the blind pouch and to guide the surgeon’s expectations regarding the length of the atretic segment to be resected at the surgical pull-through procedure.22 In patients with a cloacal disorder, a single perineal orifice is found where the urinary tract, vagina, and rectum converge into a common channel.

Table 32.1

Krickenbeck Classification of Anorectal Malformations

| Major Clinical Groups | Rare Variants |

| Perineal (cutaneous) fistula | Pouch colon |

| Rectourethral fistula | Rectal atresia or stenosis |

| Prostatic | Rectovaginal fistula |

| Bulbar | H-fistula |

| Rectovesical fistula | Other |

| Vestibular fistula | |

| Cloaca | |

| No fistula | |

| Anal stenosis |

Adapted from Holschneider A, Hutson J, Pena A, et al. Preliminary report on the international conference for the development of standards for the treatment of anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1521-1526.

Prognosis and Treatment

A posterior sagittal approach is considered the best method for defining and repairing anorectal anomalies.18 This approach has greatly improved outcomes in anorectal malformation repair over the past several decades.22,23

The level of anal atresia (i.e., high, intermediate, or low) in relation to the levator ani muscle is directly related to functional prognosis and rates of fecal continence or constipation after a surgical pull-through procedure.20 Patients with anorectal agenesis have a poor prognosis for fecal continence because they lack a functional puborectalis sling mechanism and internal and external anal sphincters. The prognosis for anal atresia located inferior to the levator ani muscle depends on the presence of functional sphincters and intact sensation. Atresias isolated to the anus, such as imperforate anal membrane, carry the best surgical prognosis.

For patients with cloacal disorders, prognostic factors include the quality of the sacrum, the quality of the muscles, and the length of the common channel. Surgical repair of a common channel less than 3 cm long is feasible for most pediatric surgeons, but for a common channel longer than 3 cm, the repair should be performed at a specialized center by an experienced surgeon.18

In the first 24 to 48 hours after birth of an infant with an anorectal malformation, the major issues are identification of life-threatening anomalies and deciding whether to repair the defect immediately or to perform a protective colostomy with repair at a later date. These decisions are based on the infant’s physical examination, the extent of the malformation, and any significant changes that occur in the first 24 hours of life. After this critical period passes and the malformation features are delineated, the surgeon can repair the defect.

Benign Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of the Anus and Anal Canal

Hemorrhoids

Clinical Features

Epidemiologic studies indicate that 4.4% of the population have hemorrhoids, although this figure is likely a gross underestimate because many patients avoid seeking medical attention. Men and women are equally affected, and the peak age at diagnosis is between 45 and 65 years of age. In the United States, whites are affected more often than blacks.24

Painless bleeding is the most common sign of hemorrhoids. Pain may occur if the hemorrhoids become thrombosed or strangulated. Hemorrhoids rarely lead to anemia, and if a patient has anemia, other potential causes should be investigated. With age, the hemorrhoidal tissue may gradually engorge and extend farther up into the anal canal, where it becomes susceptible to the effects of straining at defecation. Internal hemorrhoids usually become symptomatic only when they prolapse, become ulcerated, bleed, or thrombose. External hemorrhoids may be asymptomatic or associated with discomfort, acute pain, or bleeding from thrombosis or ulceration.

Pathogenesis

In the anal submucosa, hemorrhoids are cushions of fibrovascular and connective tissue that consist of direct arteriovenous communications, mainly between the terminal branches of the superior rectal and superior hemorrhoidal arteries. These cushions serve a protective role during defecation.11,25 Hemorrhoidal tissues may arise from abnormal dilation of the internal hemorrhoid venous plexus, distention of the arteriovenous anastomoses, prolapse of these cushions, or elevations of anal sphincter pressure with resultant vascular congestion. Any cause of elevated intraabdominal pressure, such as straining at defection, inadequate fiber intake, prolonged lavatory sitting, constipation, diarrhea, and conditions such as pregnancy, ascites, and pelvic space-occupying lesions, congest the vascular cushions.24 Portal hypertension alone is not associated with hemorrhoid formation, but hemorrhoidal bleeding in the setting of portal hypertension may be related to a coagulopathic disorder rather than venous engorgement.

Pathology

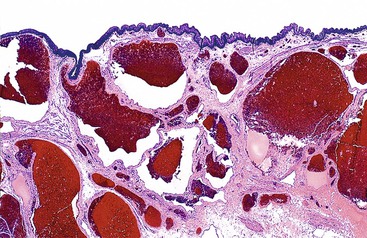

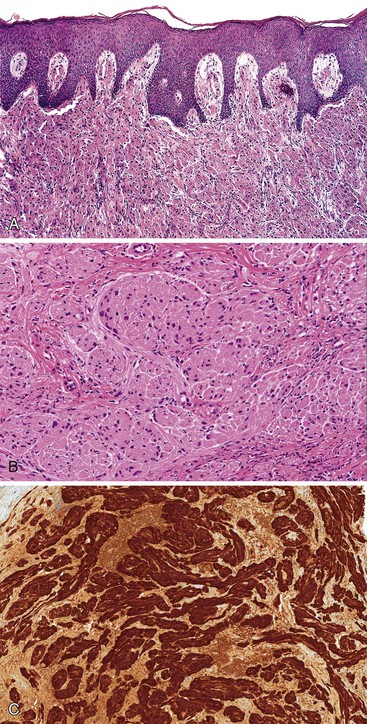

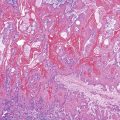

Hemorrhoidal tissue is located on the left lateral, right anterior, and right posterior aspects of the anal canal. Hemorrhoids are classified according to their site of origin; the dentate line serves as an anatomic and histologic border. External hemorrhoids originate distal to the dentate line, arising from the inferior hemorrhoidal plexus, and are lined by modified squamous epithelium. Internal hemorrhoids originate proximal to the dentate line, arising from the superior hemorrhoidal plexus, and are covered with rectal or transitional mucosa. Microscopically, excised specimens show evidence of dilated, thick-walled, submucosal vessels and sinusoidal spaces, often with thrombosis and hemorrhage into the surrounding connective tissues (Fig. 32.3).

All tissues excised as clinical hemorrhoids should be examined histologically because the differential diagnosis of an anal mass and anal bleeding includes colorectal or anal carcinoma, anal melanoma, inflammatory bowel disease, and infection.26 Anal fibroepithelial polyps (discussed later) are often confused clinically with hemorrhoids because of their similar gross appearance.

Prognosis and Treatment

Nonoperative measures, such as sitz baths, analgesics, topical anesthetics, increased dietary fiber, and stool softeners, can be offered to patients with mild symptoms or minimally symptomatic hemorrhoids. If these methods fail, sclerotherapy, rubber band ligation, cryotherapy, or surgical therapy should be considered. Surgical treatment should be tailored to each patient according to the extent of symptoms, coexisting anorectal diseases, and the degree of external anorectal component.

Complications of hemorrhoidal disease are mostly related to treatment. Mild complications include pain, urinary retention, and constipation. Severe complications include fistula formation, rectal prolapse, and incontinence.

Hypertrophied Anal Papillae or Fibroepithelial Polyps

Clinical Features and Pathogenesis

Hypertrophied anal papillae, also known as anal fibroepithelial polyps, are benign polypoid projections of anal squamous epithelium and subepithelial connective tissue. They result from enlargement of anal papillae, which are barely perceptible triangular protrusions located at the base of the anal columns (i.e., columns of Morgagni). They are found in 45% of patients who undergo proctoscopic examination and are thought to be acquired structures.27 They are twice as common in men as in women. They range in size from 0.3 to 1.9 cm, with a mean diameter of approximately 1 cm.

They may be asymptomatic, in which case they are usually found in isolation as a solitary, firm, palpable mass on digital examination or develop in association with an irritation, infection, or chronic fistula or fissure in the anal canal.27–29 They may coexist with hemorrhoids and, not surprisingly, are confused with hemorrhoids clinically.30

Pathology

Hypertrophied anal papillae or fibroepithelial polyps may have the clinical appearance of hemorrhoids and are often submitted to the pathologist with this designation.29 Unlike hemorrhoids, fibroepithelial polyps usually do not contain microscopic evidence of dilated or thick-walled vessels, recent or remote hemorrhage, or organizing thrombi. The mucosa covering the polyp is typically squamous, and the submucosal tissue is composed of the loose fibrovascular connective tissue characteristic of this region (Fig. 32.4). Some polyps may contain large, multinucleated, or stellate CD34-positive stromal cells or hyalinization of stromal vessels, likely caused by a reactive process of the stroma.31,32

Some pathologists prefer to reserve the diagnosis of hypertrophied anal papillae for cases in which the stroma is composed of loose fibrovascular tissue, and they use the term anal fibroepithelial polyp when the stroma shows predominantly fibrous changes.28 In essence, hypertrophied anal papillae and anal fibroepithelial polyps are identical to fibroepithelial polyps (i.e., acrochordons) of the cutaneous skin.

The differential diagnosis of a polypoid mass in the anal canal includes hemorrhoids, infection, abscess, and more serious disorders such as anal carcinoma or anal melanoma. Routine histologic examination is usually adequate to determine the underlying pathologic process. Occasionally, the squamous epithelium of a fibroepithelial polyp contains unsuspected intraepithelial neoplasia.

Prognosis and Therapy

Hypertrophic anal papillae tend to enlarge with time and may convert from an asymptomatic to a symptomatic mass associated with pruritus, anal discharge, and discomfort. Surgical resection in symptomatic cases often results in relief of symptoms. When anal papillae accompany an underlying chronic process, treatment often attempts to correct the primary cause and remove the hypertrophied papillae.28

Inflammatory Cloacogenic Polyps and Mucosal Prolapse

Clinical Features

Inflammatory cloacogenic polyps (ICPs) occur predominantly in middle-aged patients, although ICPs in children have been described.33 Men and women are equally affected. The most common presentation is rectal bleeding or mucous discharge. Patients who report straining at defecation are at increased risk for ICPs.

ICPs represent one aspect of mucosal prolapse disorders of the GI tract, which include inflammatory cap polyps, inflammatory myoglandular polyps, polypoid prolapsing folds of diverticular disease, colitis cystic profunda, and polyps associated with the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Any type of mucosal polyp may undergo secondary prolapse changes, with resultant misplacement of mucosal elements into the submucosa or deeper layers.

The pathogenesis of ICP is thought to be similar to that of other mucosal prolapse disorders.34 It is likely related to chronic mucosal prolapse that occurs in long-term disorders with constipation and defecation and with associated ischemic, inflammatory, and reactive changes of the overlying mucosa.35–37

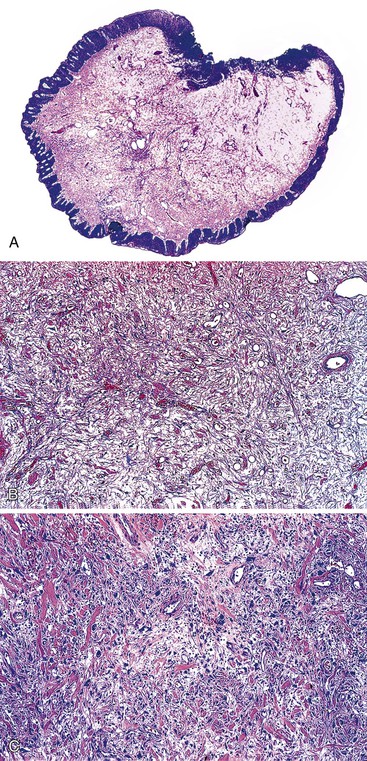

Pathology

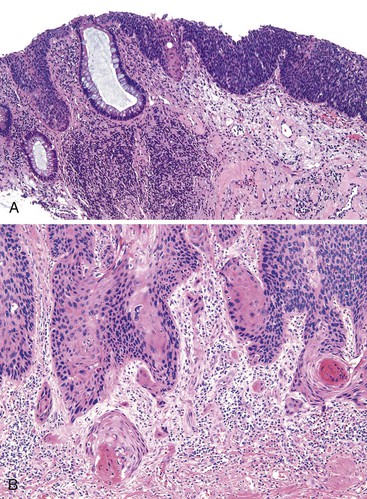

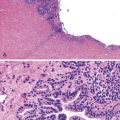

ICPs are located in the anterior anal canal, may be single or multiple, and are typically sessile (see Chapter 22). The gross size varies, but most are between 1 and 2 cm in the greatest dimension. The histologic features include fibrosis of the lamina propria, thickening of the muscularis mucosae, hyperplasia of mucosal glands (often with a villous-like configuration) leading to a serrated contour of the epithelium, and telangiectasia of surface vasculature with or without fibrin thrombi (Fig. 32.5). The muscularis mucosae is typically thickened and irregular, with frequent extension of fibromuscular strands into the lamina propria that results in the formation of diamond-shaped crypts and deposition of mucosal elastin. The finding of elastin is distinctive because it is otherwise not seen in the normal rectum. The surface epithelium is characteristically composed of a mixture of colorectal, transitional, and squamous mucosa. Ischemic-type erosion of the surface epithelium is a common finding, and it may contribute to regenerative or hyperplastic (serrated) epithelial changes.

Differential Diagnosis

A variety of entities enter into the differential diagnosis of an ICP.38 Because of their location in the anal canal and low-power appearance, ICPs may resemble tubulovillous adenomas or traditional serrated adenomas of the distal rectum. Recognition of the regenerative (non-neoplastic) epithelial cytology and eroded surface in ICPs and of the absence of cytologic dysplasia helps to distinguish an ICP from an adenoma. ICPs typically contain transitional and squamous epithelium. The fact that adenomas are somewhat uncommon in the age group in which ICPs are often diagnosed is also useful.

In some ICPs, prominent misplacement of the reactive epithelium into the underlying fibrous stroma combined with hyperplastic musculature, also known as proctitis cystica profunda, may simulate an invasive mucinous carcinoma (see Chapter 22). Although prolapse changes may also be found in invasive carcinomas, they are more prominent in ICPs, and the misplaced epithelium is usually accompanied by lamina propria tissue. Non-neoplastic epithelium surrounding mucin pools may be found in cases of benign proctitis cystica profunda, whereas neoplastic epithelium is often found floating within mucin pools in cases of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma. In some cases, features of prolapse may be the only finding in the mucosa overlying a malignancy, and an underlying malignancy should always be considered when biopsy findings of a mass lesion reveal prolapse changes but no neoplasm.39

The finding of inflammation and a granulation tissue cap may cause diagnostic confusion with a juvenile or hamartomatous polyp or an inflammatory polyp (i.e., inflammatory bowel disease-related or sporadic).38 This distinction may be particularly difficult because any type of colorectal polyp can undergo secondary prolapse. A low-power view of the polyp often helps the pathologist to differentiate prolapse from an injury resulting from a preexisting (often neoplastic) lesion. ICPs show muscularization in the base of the polyp, whereas juvenile or inflammatory polyps never have this feature. Inflammatory polyps in inflammatory bowel disease usually occur in the context of chronic colitis in adjacent mucosa.

Simple excision of ICPs is usually curative.36 Recurrences are uncommon.

Inflammatory Disorders of the Anal Canal

Anal Tears, Fissures, and Ulcers

Clinical Features

Acute anal fissures are common, although the exact incidence is unknown because most patients do not undergo clinical evaluation.40 Chronic anal fissures affect men and women equally, and they account for as many as 10% of patients who are seen in colorectal clinics. Although there are no uniform criteria, chronicity of an anal fissure usually is defined as persistence for at least 6 weeks with transverse internal anal sphincter fibers visible on anoscopy. Other features of chronicity include an indurated edge and a hypertrophic anal papilla. When fissures become large, deep, and chronic, they are often referred to as an anal ulcer.

Pathogenesis

The term anal tear refers to an acute linear tear in the mucosa of the anal canal. Although most anal tears heal spontaneously, the development of an anal fissure is associated with spasm of the internal anal sphincter and a reduction in mucosal blood flow that leads to delayed or failed healing of the initial mucosal injury.41 Chronic anal fissures are further propagated by increased resting internal anal sphincter tone. In patients with a normal sphincter tone, other factors have been linked to the development of an anal fissure, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, anal-receptive intercourse, sexual abuse, Crohn’s disease, and previous obstetric operations or anorectal malformation repair.40

Pathology

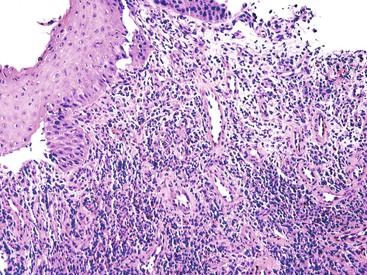

Anal fissures typically extend from the dentate line to the anal verge in the posterior midline of the anal canal overlying the lower portion of the internal sphincter. Histologically, anal fissures or ulcers are characterized by nonspecific acute and chronic inflammation, granulation tissue, and reactive changes of the squamous epithelium at the edges of the fissure (Fig. 32.6). Chronic fissures are frequently associated with hypertrophy of the anal papillae at the proximal end of the lesion.41 Histologically, hypertrophic anal papillae are similar to other types of benign fibroepithelial polyps. When a fissure is located in an unusual location or fails to heal after treatment, inflammatory bowel disease (usually Crohn’s disease), neoplasm, or infectious processes should be considered.42–44

Prognosis and Treatment

Most acute fissures are superficial and heal quickly. Healing may be facilitated by increased dietary fiber and warm sitz baths. For chronic anal fissures, medical management is recommended for first-line treatment with the aim of reducing internal anal sphincter resting pressure.40,45,46 Medical treatments include the use of nitric oxide donors such as topical glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) to increase anodermal blood flow and botulinum toxin to reduce resting internal anal sphincter tone.

If these methods fail or the fissures recur, surgical management may be indicated by using approaches such as anal dilation, internal sphincterotomy, or fissurectomy.41 Surgical management permits healing of chronic fissures in as many as 100% of patients, and rates of recurrence are low.40 Patients with recurrent anal fissure after surgical management should be evaluated for alternative causes, such as Crohn’s disease, sexually transmitted disease, sexual abuse, and HIV infection.

Anal Abscesses and Fistulas

Most anal fistulas or abscesses are idiopathic, although they may occur in patients with Crohn’s disease or carcinoma in this region.47 Anorectal abscesses may also be found in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.48–50 In hidradenitis patients, wound healing is often complicated by coexistent obesity and diabetes.

Anal abscesses and fistulas represent different stages of anorectal suppurative disease. Most suppurative processes in this location arise after infection of an anal duct, which provides a pathway from the anal canal to perineal soft tissues.51,52 In the acute phase, an abscess may form, whereas a fistula represents the chronic phase of infection, occurring in 30% to 50% of patients with an anal abscess.53,54 There are no reliable ways to predict which patients will have disease progression to a fistula.

Histologic specimens obtained from fistulas show nonspecific acute and chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and granulation tissue. A giant cell foreign body reaction to fecal matter may be seen in specimens from fistula tracts of the anus and should not be confused with the well-formed, sarcoid-like granulomatous reaction typical of Crohn’s disease. In patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, the histologic findings in the anal canal are identical to those in other affected locations.

Any cause of infection or fistula formation should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an anal abscess or fistula. A thorough histologic examination, including multiple sections, should be conducted to rule out an underlying neoplasm, and special stains for acid-fast bacilli, fungi, or other infectious organisms should be performed, particularly if granulomatous inflammation is found. The patient’s clinical history, including inflammatory bowel disease, should be carefully reviewed.

Antibiotics are often ineffective because of poor penetration into inflamed areas. Incision and drainage remain the primary treatment modality for anal abscesses, but recurrences are relatively common54 Wide surgical excision is curative in most cases of idiopathic anal abscess or fistula.

Common Infections of the Anal Canal

Clinical Features and Pathogenesis

Individuals who engage in unprotected anal intercourse are at greatest risk for acquiring anorectal infections. Anorectal infections are most common among men who have sex with men (MSM). The symptoms of an anorectal infection depend on the specific infection or pathologic process but are often indistinguishable from those of inflammatory bowel disease. The most common symptom is a frequent or continuous urge to have a bowel movement. Other symptoms include anorectal pain or discomfort, anal discharge (i.e., purulent, mucoid, or blood stained), tenesmus, urgency of defecation, rectal bleeding, and constipation. Systemic symptoms such as fever may also occur, but many patients are asymptomatic.55

Infections of the anal canal are most often caused by sexually transmitted pathogens. The most common agent identified is Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhea), found in 30% of patients, followed by Chlamydia trachomatis (19%), herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2 (16%), and Treponema pallidum (syphilis; 2%). HSV type 1 accounts for 13% of anorectal herpes infections and likely represents anal-oral transmission.55 The incidence of anorectal disease caused by C. trachomatis, the causative agent of lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), is increasing.56,57 More than one infection may exist in a single individual.

Pathology

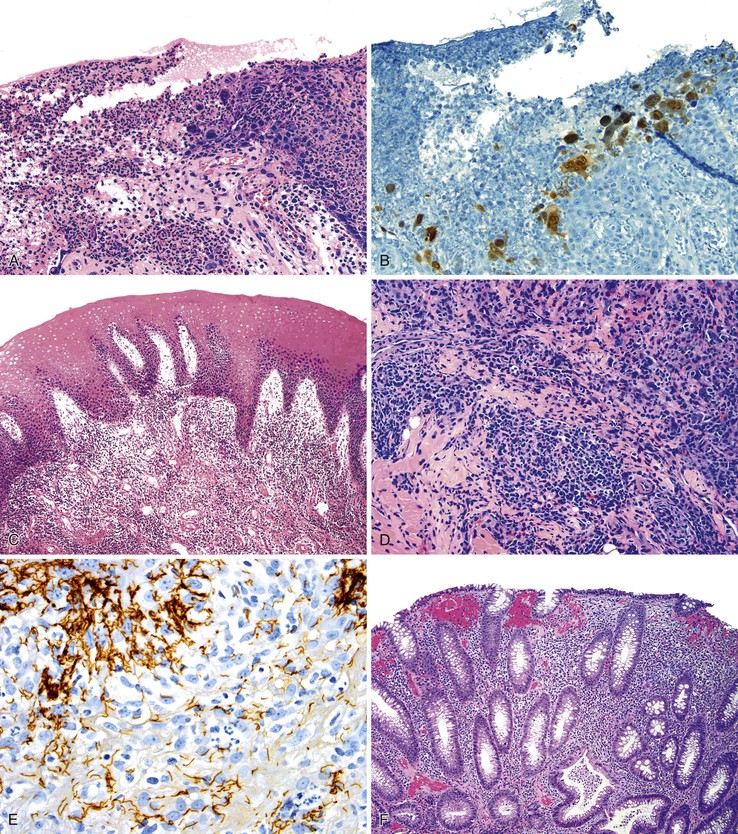

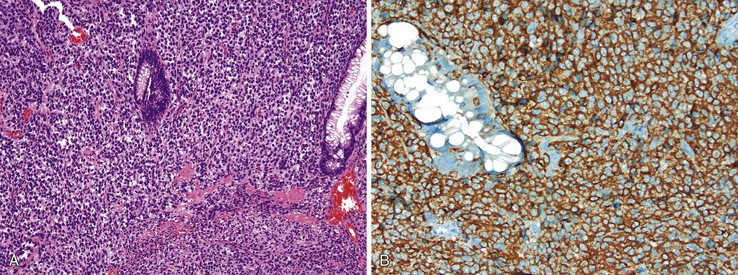

Different pathogens infect different types of mucosa. HSV and T. pallidum infect the stratified squamous epithelium of the perianal area and anal verge. As in other sites, HSV infections are associated with small vesicles that ulcerate and are seen histologically as mucosal ulcerations with associated acute and chronic inflammation and granulation tissue. Virally infected multinucleated cells with smudged chromatin may be seen in routine sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, although immunohistochemical stains are of great value in confirming the presence of virally infected cells (Fig. 32.7, A and B). In contrast, syphilis is commonly associated with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate rich in plasma cells and may show associated granulomatous inflammation (see Fig. 32.7, C to E).

Dark-field microscopy of exudates from anorectal ulcers may be inaccurate because of contamination from commensal spirochetes found in the normal flora of the colorectum; however, T. pallidum immunohistochemical stains have become a useful tool for surgical pathologists.58 Demonstration of antibodies in the serum confirms the syphilis diagnosis. Serologic tests for syphilis include the use of nonspecific cardiolipin antigens (i.e., Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] slide test and rapid plasma reagin [RPR] test). These tests can be used to diagnose primary and secondary syphilis and to monitor treatment response. The specific treponemal antigen tests (i.e., enzyme immunoassay, T. pallidum hemagglutination assay, T. pallidum particle agglutination assay, and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test) remain positive even after successful treatment and can detect latent syphilis in untreated adults.

Infections occurring between the anal verge and the dentate line tend to be extremely painful because of the abundance of sensory nerve endings in this area. Chlamydial infections and gonorrhea target the columnar epithelium of the rectum. The pathologist may see evidence of cryptitis, crypt abscesses, and reactive epithelial changes in affected individuals (see Fig. 32.7, F). Granulomas may occur. Polymerase chain reaction amplification for C. trachomatis DNA is the standard diagnostic test for anorectal chlamydial infection. Because the rectum has few sensory nerve endings, infections that spare the anus may be painless.55

Differential Diagnosis

A solitary anal ulcer (e.g., in HSV infection) may be misdiagnosed clinically as a chronic anal fissure. Granulomatous inflammation can lead to the formation of a rectal mass in primary and secondary syphilis, and it must be differentiated from other causes of a rectal mass, such as a neoplasm. Condylomata lata occurring in the perianal region in syphilis patients appear as moist, wartlike lesions, and they may be confused with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The pain, tenesmus, bloody discharge, and constipation of untreated LGV may mimic Crohn’s disease. In the tertiary stage, anorectal fistulas and strictures may occur in LGV.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

The histopathologic features of inflammatory bowel disease are detailed in Chapters 16 and 17. However, involvement of the anal canal is sufficiently common to warrant additional comments, particularly because neoplastic disorders may manifest with similar findings in this region.

Clinical Features and Pathogenesis

In ulcerative colitis, involvement of the anus is typically nonspecific and indistinguishable from the appearance in patients without colitis. In contrast to ulcerative colitis, at least 50% of patients with Crohn’s disease have perianal or anal disease.59 The anal canal is involved in approximately 25% of patients with small intestinal Crohn’s disease, more than 40% of patients with large bowel disease and rectal sparing, and more than 90% of patients with large bowel disease that includes the rectum.60 In some patients, anal involvement is the first or only clinical manifestation of Crohn’s disease.61

The clinical features of Crohn’s disease involving the anus have been well characterized.61,62 Symptoms include recurrent sepsis, local pain, discharge, ulceration, fecal incontinence, sleep disruption, psychological disturbance, and sexual dysfunction.63 Signs most characteristic of Crohn’s disease affecting the anus are chronic inflammatory changes, induration of the anal skin, multiplicity of lesions, and skin discoloration. Anal canal lesions include fissures, ulcers, strictures, perianal fistulas that open into or near the anal canal, abscesses, rectovaginal fistulas in women, and cancer.59 Anal skin lesions are usually perianal skin tags or hemorrhoids. Anal skin tags are the most common finding and tend to be larger than those from patients without Crohn’s disease. Fissures and fistulas are the next most common finding.59 Fissures in Crohn’s disease tend to be large, deep, and located more atypically compared with traumatic anal fissures. Most fistulas in anal Crohn’s disease are classified as simple (see Prognosis and Treatment), although in some patients, they may contain multiple openings, sometimes occurring at a considerable distance from the anal canal (i.e., watering-can perineum).61 The cause of Crohn’s perianal fistulas is uncertain, but in some patients, it is thought to be a fistula-in-ano arising from inflamed or infected anal glands or penetration of fissures or ulcers in the rectum or anal canal.61

Pathology

In ulcerative colitis, chronic active inflammation tends to involve rectal mucosa in the proximal anal canal.64 If histologic findings are encountered more distally in the anal canal, they are limited to nonspecific chronic inflammation of the submucosal tissues with associated mild reactive changes of the squamous or transitional epithelium. Anal fissures, abscesses, or fistulas are occasionally found, and these more severe changes should prompt clinical consideration of Crohn’s disease.

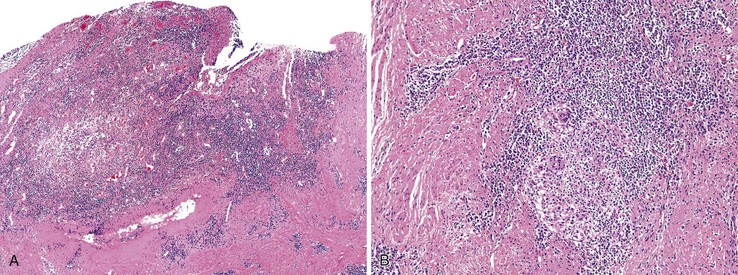

The anal findings in Crohn’s disease vary. They include anal fissures, fistulas, ulcers, abscesses, and tags.61 Unfortunately, the histologic features seen in Crohn’s-related fissures or fistulas are not different from those in patients without Crohn’s disease. A feature supporting the diagnosis of anal Crohn’s disease is sarcoid-like (noncaseating) granulomatous inflammation close to the anal mucosa, particularly in a young person with no other obvious reason for an inflammatory disorder of the anal canal (Fig. 32.8). As in other GI sites, a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease requires correlation of the histologic changes with all available clinical, endoscopic, and radiologic information.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of granulomatous inflammation in the anal canal includes foreign body reaction to nonspecific fistulas, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, granuloma inguinale caused by Calymmatobacterium granulomatis, and LGV caused by sexual transmission of C. trachomatis.55,65–67 Tuberculous granulomas are typically caseating. Stains for acid-fast bacilli and other microbiologic studies are helpful. Patients with tuberculosis of the anal canal invariably have pulmonary disease. The finding of Donovan bodies with a Warthin-Starry stain supports a diagnosis of granuloma inguinale, whereas the finding of follicular lymphohistiocytic and plasma cell infiltrates in association with neural hyperplasia may suggest chlamydial infection.68 Hidradenitis suppurativa may be confused with complex fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease. A correct diagnosis can often be made by examination under anesthesia and by probing the cutaneous tracts and demonstrating that they traverse only to the subdermal space and do not communicate with the rectum or other parts of the digestive tract.69

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with anal Crohn’s disease is related to the extent of involvement, and for most patients, it is excellent.70 Various classification schemes for perianal Crohn’s disease have been proposed, although most are not widely used because they have not shown a reproducible relation to meaningful clinical outcomes, such as fistula formation.61 Most clinicians classify perianal disease as simple or complex.

Proper classification involves thorough evaluation of the perianal area for involvement by skin tags, fistulas, fissures, abscesses, and stricturing disease and an endoscopic examination of the rectum to assess for inflammation. Fistulas may be classified as simple, indicating that the fistula tract arises below the external sphincter, has a single external opening, has no pain or fluctuation to suggest perianal abscess, is not a rectovaginal fistula, and has no evidence of anorectal stricture. Complex fistulas arise above the external anal sphincter and may contain one or more of the features described. Rectal Crohn’s disease may make a simple fistula more complicated to manage, but overall, patients with Crohn’s disease and simple fistulas have higher rates of healing than non-Crohn’s patients with complex fistulas.71

Treatment

Management of perianal Crohn’s disease includes medical and surgical treatment. It most often begins with conservative medical treatment that includes antibiotics, steroids, antimetabolites such as azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine, anti–tumor necrosis factor-α agents, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine. These agents are used to reduce the number of draining fistulas and are most effective in simple perianal disease.61,71

Combined with small bowel disease, perianal Crohn’s disease is an absolute contraindication to restorative proctocolectomy (i.e., ileal pouch anal anastomosis) in the otherwise well-motivated subset of Crohn’s patients seeking a continence-preserving procedure.72 Surgical management is reserved for patients with complex fistulizing disease. As many as 50% of patients require surgical management of their perianal disease, ranging from local procedures such as sepsis drainage and seton placement to segmental resections such as proctectomy with ostomy creation.61,71

Benign Tumors of the Anal Canal

Adnexal Tumors

Clinical Features

Many adnexal tumors have been described in the perianal skin. The most common lesion is hidradenoma papilliferum.73,74 Hidradenoma papilliferum occurs almost exclusively in women and within a wide age range. In most patients, it manifests as a solitary, painless mass of the perianal skin or perineum, although ulceration of the overlying skin has been reported in some cases.74 Rarely, trichoepitheliomas or apocrine gland adenomas may arise in the perianal skin.75,76 Trichoepitheliomas occur in both sexes and may reach several centimeters in diameter when they occur in the perianal skin, unlike trichoepitheliomas of other skin regions.75

Most adnexal tumors of the perianal skin have an apocrine or sweat gland origin, although trichoepitheliomas are derived from hair follicles. Immunolabeling for estrogen and progesterone receptors provides a reliable marker for anogenital sweat glands in women but not conventional sweat glands, in keeping with the fact that benign apocrine gland tumors occur almost exclusively in the female anogenital region.74

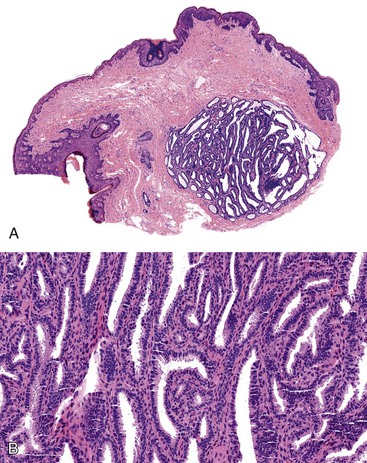

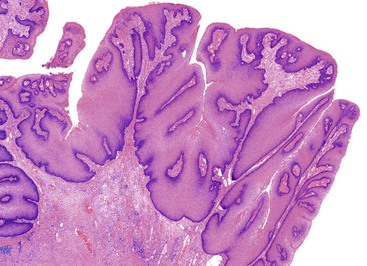

Pathology

Grossly, perianal adnexal tumors appear as solitary subcutaneous nodules with a smooth red to tan surface, although cases of ulceration mimicking a more aggressive lesion have been reported.77 In the case of hidradenoma papilliferum, pathologic examination reveals a complex papillary glandular pattern characterized by a prominent myoepithelial layer. Some stratification of the epithelial cells and mild pleomorphism may be seen (Fig. 32.9). Trichoepitheliomas often appear as a solid mass without ulceration of the overlying skin. Histologic examination reveals uniform eosinophilic cells with centrally located, minimally atypical nuclei. The epithelial cells form tracts throughout the supportive stroma that are two or more cells thick, and they form pseudopapillae in regions of loose matrix, reminiscent of abortive pilar differentiation.78 Local excision is usually curative.

Differential Diagnosis

In the case of hidradenoma papilliferum, the finding of a solitary perianal mass with ulceration may indicate a more aggressive lesion, such as an infiltrating squamous carcinoma. The main differential diagnosis of a trichoepithelioma is basal cell carcinoma, because both lesions consist of a proliferation of basaloid cells. The formation of pseudopapillae is characteristic of trichoepitheliomas, whereas peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact are important features of basal cell carcinomas.78,79

Granular Cell Tumor

Clinical Features and Pathogenesis

Granular cell tumors are common benign tumors that originate from Schwann cells. They occur in many locations, including the GI tract. When the GI tract is involved, the perianal region is a common site (21% in a large series).80,81 They are most commonly diagnosed in adults in the fifth decade of life and are more common in women. The most common presentation is an incidental, asymptomatic, solitary mass.80

Pathology

Grossly, granular cell tumors appear as firm, solitary subcutaneous nodules that are white or yellow on cut section. Histologically, these lesions are composed of sheets of cells with small, uniform, hyperchromatic nuclei and with characteristic eosinophilic granular cytoplasm that is diastase resistant on periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining. The granularity of the cytoplasm corresponds to vacuoles that contain cellular debris, which is evident by electron microscopy (Fig. 32.10).

The distinctive histologic features of a granular cell tumor can distinguish it from other subcutaneous perianal masses. A positive immunostain for S100 protein may be used to support the diagnosis of a granular cell tumor. These tumors are also strongly positive for CD68 (KP1). Of particular significance is the occurrence of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epithelium overlying granular cell tumors in as many as 50% of cases, which may be mistaken for an infiltrating squamous carcinoma.80 S100 protein–positive granular cells located immediately beneath the atypical epithelium should help to indicate its benign nature. Local excision is usually curative.

Squamous Neoplasms of the Anal Canal

Risk Factors and Pathogenesis

Risk factors for squamous tumors and neoplasms of the anal canal include anal-receptive intercourse, heavy smoking, a history of sexually transmitted diseases, HIV-positive status, and immunosuppression.82–86 In one study, 92% of HIV-positive MSM demonstrated evidence of anal HPV infection, compared with 66% of MSM who were HIV negative. In women, lower genital tract squamous neoplasia is a risk factor, and numerous similarities to the incidence and epidemiology of cervical and vulvar neoplasia have been observed.87 Women with multifocal genital intraepithelial neoplasia have a 16-fold increase in the rate of anal canal intraepithelial neoplasia.86 Solid organ transplant recipients have a 10- to 100-fold increased risk of anogenital neoplasia.

There are more than 100 types of HPV. Of the approximately 30 types that infect the anogenital tract, the most common are 6, 11, 16, and 18.88 The finding of HPV in an anal carcinoma is related to the sensitivity of the technique used,89 but some evidence suggests geographic or population differences in HPV genotypes associated with anal cancers. The prevalence of HPV-16–associated anal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was found to be significantly lower in India and South Africa compared with more developed countries.90

Although HPV infection is identified in more than 80% of anal SCC,91 it is not sufficient to cause malignancy by itself. Evidence for this claim is largely related to two phenomena. First, HPV infection is highly prevalent among sexually active individuals, but cancer does not develop in most patients infected with high-risk genotypes (discussed later).92,93 In most patients, cell-mediated immunity is responsible for clearance of the infection, and neutralizing antibodies prevent subsequent infections.94 Second, in experimental studies, infection with high-risk (oncogenic) HPV genotypes is insufficient to induce transformation and tumor progression95,96 This may reflect the inability of HPV to integrate into the host genome. For example, in benign lesions, the viral genome replicates as an extrachromosomal episome, whereas in malignant tumors, the viral genome becomes integrated into the host cell chromosomes.97–100 Viral integration does not appear to occur randomly. In a systematic review of known HPV integration sites, integration at 8q24, the location of the MYC oncogene, and 3p14, the location of the FHIT tumor suppressor gene, were the most common sites reported.101

High-risk HPVs, most commonly genotypes 16 and 18, but also 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 50, 51, 53, 56, 58, 59, 68, and others, encode for at least three oncoproteins, known as E5, E6, and E7, which are growth stimulating and have transforming properties. With integration of HPV DNA into the host genome, E6 and E7 expression is increased.102 The E6 protein binds to the TP53 tumor suppressor protein, which is encoded by the TP53 gene and is a critical regulator of cell growth and response to stress103,104 E6 binding to TP53 leads to its rapid degradation.104 Similarly, E7 protein binds to and inactivates the retinoblastoma-associated protein (RB1) tumor suppressor protein, which normally restricts cell proliferation to the basal layer.105–107 In most human cancers with TP53 or RB1 mutations, the proteins are inactivated. However, wild-type TP53 and RB1 genes are common in anogenital cancers.108–111 By inactivating TP53 and RB1 and deregulating cellular growth, the action of E6 and E7 on these tumor suppressor proteins appears functionally equivalent to genetic mutations and increases the risk of anogenital cancer. Consistent with this notion, HPV-negative cervical and anal cancers have been found to harbor inactivating mutations in TP53 and RB1.111,112

HPV integration promotes general changes of the host genome, such as chromosomal instability. The degree of chromosomal instability is highly correlated with levels of E7 overexpression, although whether the instability precedes or follows viral integration is unclear.113–115 Recurrent chromosomal alterations associated with chromosomal instability have been described in anal squamous carcinoma that include deletion of chromosome arms 11q, 3p, 4p, 13q, and 18q and nonrandom copy number increases of chromosomes 17 and 19.116,117 In contrast, chromosomal instability is relatively uncommon in anal carcinomas of HIV-positive patients, suggesting that immunosuppression may promote carcinogenesis through an alternate pathway.118,119

There is no known association between any HPV subtype and specific tumor morphology. However, HPV-6 and HPV-11 are most likely to be associated with condyloma acuminatum, and HPV-16 and HPV-18 are found in a significant minority of conventional condylomata and in lesions with high-grade dysplasia89,120–122 Verrucous carcinoma is most commonly associated with infection by HPV subtypes 6 and 11, although occasionally HPV-16 and HPV-18 have been found in these lesions.123–125 Similar to the documented progression of HPV-associated premalignant conditions of the uterine cervix, epidemiologic studies indicate that the development of anal canal intraepithelial neoplasia is associated with infection by HPV-16 and HPV-18 and less commonly by HPV-6 and HPV-11.126,127

Evidence in support of the precursor potential of anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (ASIN) lies in its close similarity to dysplasia of the uterine cervix, including histologic similarities between the preinvasive and invasive lesions, its occurrence at a younger average patient age compared with its invasive counterpart, and its common occurrence adjacent to invasive cancers, particularly those associated with HPV infection in MSM.84,86 Perianal intraepithelial neoplasia, including bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease, also have an association with HPV infection; in particular, HPV-16 has been demonstrated in bowenoid papulosis and Bowen’s disease.128,129

HPV vaccines have been developed to protect recipients against HPV types 16 and 18 (HPV2/Cervarix, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium) and HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 (HPV4/Gardasil, Merck, West Point, PA). These vaccines were first approved and recommended for administration to girls in 2009 and 2006, respectively; in late 2011, HPV4/Gardasil was recommended for administration to boys.130 One analysis found that vaccinating boys and girls, rather than girls alone, could reduce the HPV-related cancer burden in boys by 65% compared with girls-only vaccination. The investigators further estimated that inclusion of boys in a HPV vaccination program would lead to an 86% reduction in the incidence of anal cancer compared with a 63% reduction with girls-only vaccination.131

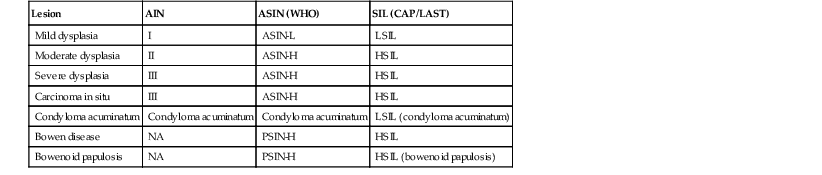

Nomenclature of Preinvasive Anal Squamous Neoplasia

During the past several decades, various terms have been used to describe the same anal squamous pathology. Consensus groups such as the AJCC, the Bethesda System, and the World Health Organization (WHO) have used different nomenclature. This chapter uses the WHO nomenclature, but a brief discussion of the latest attempt at unifying squamous neoplasia nomenclature is warranted because it may become standard in the future (Table 32.2).

Table 32.2

Nomenclature for Preinvasive Anal Squamous Lesions

| Lesion | AIN | ASIN (WHO) | SIL (CAP/LAST) |

| Mild dysplasia | I | ASIN-L | LSIL |

| Moderate dysplasia | II | ASIN-H | HSIL |

| Severe dysplasia | III | ASIN-H | HSIL |

| Carcinoma in situ | III | ASIN-H | HSIL |

| Condyloma acuminatum | Condyloma acuminatum | Condyloma acuminatum | LSIL (condyloma acuminatum) |

| Bowen disease | NA | PSIN-H | HSIL |

| Bowenoid papulosis | NA | PSIN-H | HSIL (bowenoid papulosis) |

AIN, Anal intraepithelial neoplasia; ASIN-H, high-grade anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia; ASIN-L, low-grade anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia; CAP/LAST, College of American Pathologists/Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Project; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; NA, not applicable; PSIN, perianal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia; SIL, squamous intraepithelial lesion; WHO, World Health Organization.

In 2012, the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology released the product of a joint Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) Project, in which the groups reported their recommendations for a unified terminology for all HPV-related squamous lesions in the lower anogenital tract.132 They contended that the clinical, epidemiologic, and biologic similarities between the various anogenital sites justified the use of a single nomenclature for HPV-associated lesions. When presented with a lesion, a pathologist cannot reliably predict from which site it was derived (e.g., cervix, vagina, anus) or whether it came from a male or female patient. There are no differences in the molecular or biomarker phenotypes in the various HPV-related lower anogenital sites.

The CAP/LAST investigators contend that HPV interacts with all the anogenital squamous epithelium by two basic mechanisms. Squamous cells transiently support the virus, which manifests as a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL). Alternatively, precancerous lesions resulting from viral oncogene expression cause a clonal proliferation of relatively undifferentiated cells in a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). With time, persistent HPV infection results in a substantial risk of malignancy. In the LAST nomenclature, additional pathologic descriptors such as ASIN, condyloma acuminatum, or bowenoid papulosis may be added in parentheses as needed.

Some investigators and clinicians are skeptical of applying the cervical HPV screening and treatment paradigm to anal pathology. They cite reasons such as unclear natural history data for anal HPV infection. Many of the studies of anal squamous neoplasia focus on MSM, which may be a significantly different population from women with cervical neoplasia. For example, HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia tend to persist in MSM as the population ages, whereas cervical HPV infection and intraepithelial neoplasia dramatically decrease with patient age.91 Some researchers report high-grade anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (ASIN-H) with a relatively high risk of progression to invasive carcinoma; Scholefield and colleagues estimate 10% at 5 years.133 However, one meta-analysis estimates the risk to be much lower: 0.15% per year for HIV-positive MSM and 0.02% per year for HIV-negative MSM.91 No randomized trials have investigated the benefits and risks of managing ASIN.

Condyloma Acuminatum

Clinical Features

Condyloma acuminatum (i.e., common anogenital wart) is the most common tumor of the anal and perianal region.120 These lesions typically grow on warm, moist mucosal regions, characteristic of the anogenital skin. As many as 1% of sexually active people have anal condylomata, and the lesions often occur in association with other sexually transmitted diseases.89 Anal condylomata may be associated with penile warts in men or vulvar warts in women, but they may also occur as the sole area of infection, particularly in the MSM population. Nonsexual transmission may occur, particularly in children.134

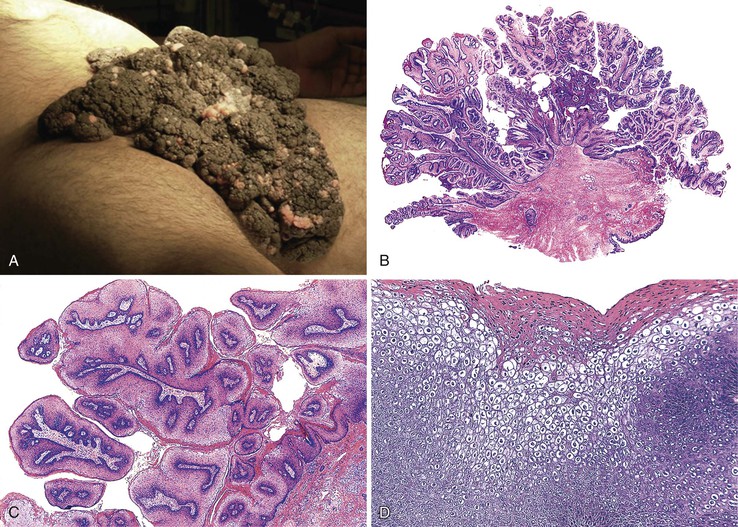

Pathology

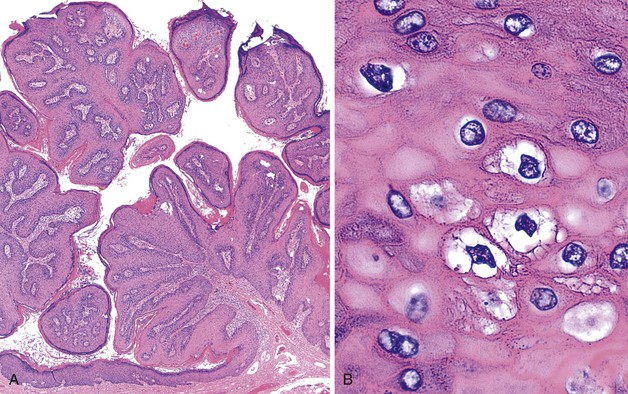

The perianal skin is the most commonly affected area, although condylomata located solely within the anal canal may occur. Grossly, condylomata are soft, fleshy, and tan, gray, or pink papillomatous growths that often occur in groups or clusters.

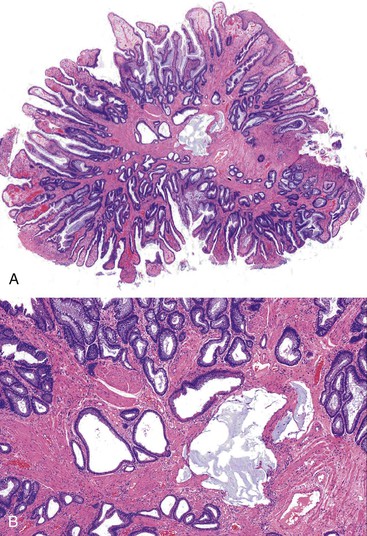

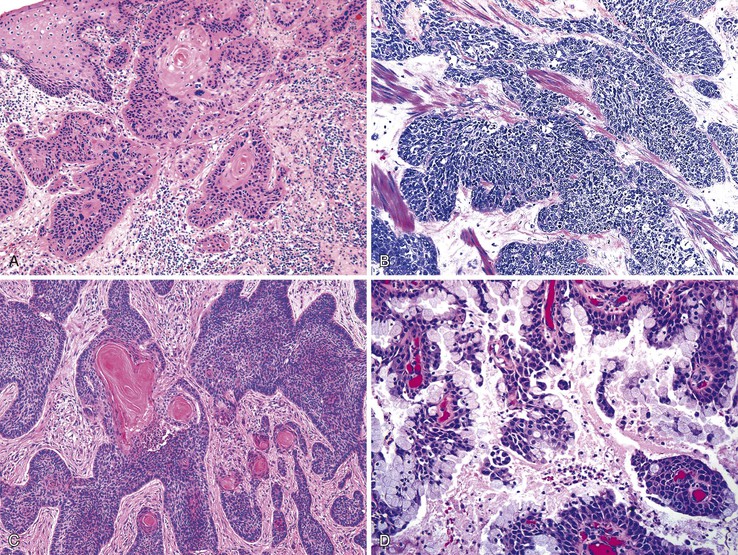

Histologically, the papillomatous appearance is best appreciated at low magnification. The squamous epithelium shows marked acanthosis and a variable expansion of the stratum corneum layer. Surface parakeratosis is common. The rete pegs may appear elongated with broad bases. On higher magnification, the surface epithelium contains squamous cells with an enlarged, irregular, and hyperchromatic nucleus and an accompanying perinuclear halo. These cells, known as koilocytes, are the histologic hallmark of HPV infection (Fig. 32.11). Dyskeratotic cells are usually easily found, as well as multinucleate cells, which are also characteristic of HPV infection. Basal cell hyperplasia is typically associated with orderly and progressive maturation of the epithelium. The squamous epithelium is well delineated from the underlying stroma, which often contains chronic inflammation, edema, and vascular dilation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of condyloma includes verrucous carcinoma on one end of the spectrum and benign anal or perianal lesions, such as seborrheic keratosis, fibroepithelial polyp, and prolapse-type polyp, on the other end. Condyloma acuminatum may be impossible to distinguish from verrucous carcinoma, particularly in biopsy samples or when the clinical impression is not provided. Verrucous carcinomas are usually larger than condylomata acuminata, and verrucous carcinomas display exophytic and endophytic growth patterns, whereas condylomata usually are only exophytic. Separating condyloma from another type of benign lesion rests on identifying an HPV cytopathic effect in the condyloma or the characteristic histologic features in the other benign lesions. Immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization studies for HPV can be helpful in equivocal cases.

Prognosis

There is controversy regarding the malignant potential of condylomata. Although they usually harbor low-risk HPV genotypes, as many as 35% demonstrate high-risk HPV, most commonly genotypes 16 and 18.122 High-grade intraepithelial neoplasia has been described in as many as 20% of HIV-infected patients with condylomata, and cases of invasive squamous carcinoma arising in an anal condyloma have been reported.121

Treatment

The most common treatments for anal condylomata are ablative or cytodestructive.135 Methods of ablative treatment include cryotherapy, local excision, electrocautery, and laser therapy. Cytodestructive therapies include podophyllotoxin and trichloroacetic acid. Both forms of treatment are associated with a high recurrence rate, which is attributed to latent HPV in clinically unremarkable adjacent epithelium. Immunosuppression is also associated with an increased rate of recurrence after surgical removal.136 The immunomodulatory agent imiquimod has potent antiviral and antitumor activity without the common side effects of the other forms of treatment.137

Anal Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Clinical Features

Anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (ASIN), as listed in the WHO nomenclature, may be found in tissues removed for a variety of disorders.138 Similar to its cervical counterpart, ASIN has been identified in anal mucosa adjacent to invasive carcinomas of the anal canal and has been an incidental finding in resection specimens from this region.139

Its prevalence in the general population is estimated at 2 to 3 cases per 1000 individuals, but the prevalence is much higher in at-risk populations, such as MSM, HIV-positive individuals, women with cervical or vaginal squamous carcinoma, and immunocompromised individuals.138,140 ASIN has been documented at much greater frequencies in HIV-positive MSM compared with MSM who are HIV negative. For example, one study found ASIN in 36% of HIV-positive men and 7% of HIV-negative men.141 The difference also seems to hold true for ASIN-H; 49% of HIV-positive MSM had ASIN-H and 17% of HIV-negative MSM had ASIN-H in one study.142

Clinically, ASIN may appear as raised, scaly, white, erythematous, pigmented, fissured, or ulcerated areas in the anal canal, although it is often subclinical and may be an incidental finding.143 ASIN may also be identified as acetowhite epithelium, which contrasts with iodine-positive non-neoplastic mucosa by anal colposcopy.

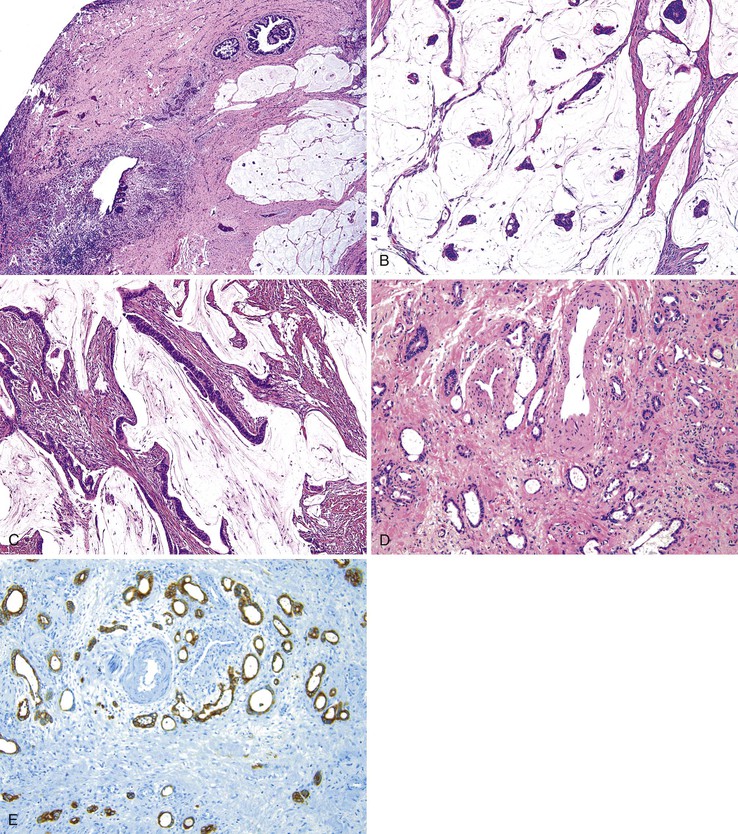

Pathology

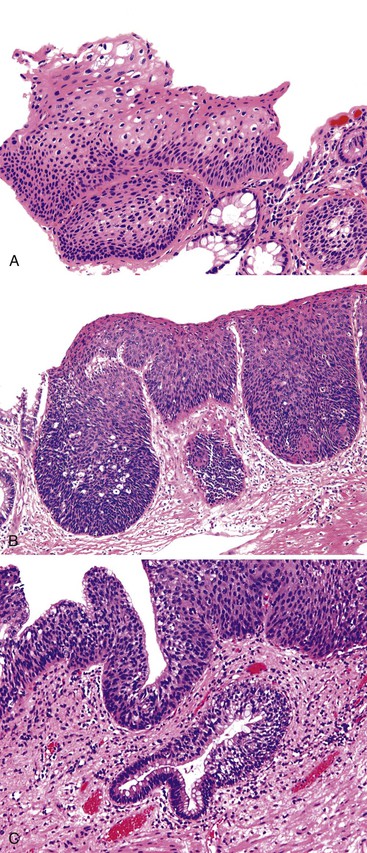

ASIN is characterized by cells with enlarged nuclei, irregular nuclear membranes, and increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratios, with a lack of cytoplasmic maturation toward the luminal surface.132 Mitotic figures may be encountered beyond the normal regenerative basal zone of the squamous epithelium. Individual cell keratinization and dyskeratosis are common and may represent markers of HPV infection. These changes typically occur in the absence of inflammation.

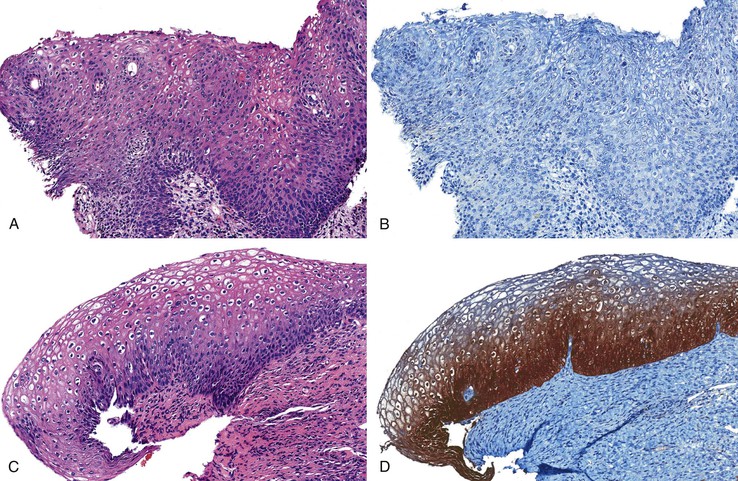

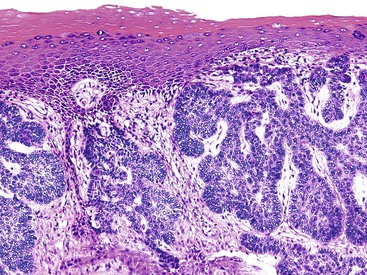

ASIN is divided into two grades, primarily based on the level at which orderly cytoplasmic maturation begins and the level at which mitotic activity stops. In low-grade anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (ASIN-L), mitotic figures and cellular pleomorphism are predominantly located in the basal third of the epithelium, with evidence of surface maturation in the upper two thirds or evidence of an HPV cytopathic effect (i.e., koilocytic atypia) is present. In contrast, ASIN-H is characterized by cellular pleomorphism, mitotic figures, and lack of cytoplasmic maturation extending into the middle and superficial thirds of the epithelium (Fig. 32.12). These preinvasive changes may colonize the underlying anal ducts and glands, which may not be detected or excised during treatment. Intraepithelial neoplasia that extends into the ducts can be graded using the same principles as surface dysplasia; however, the pathologist must be cautious with the use of tangential sectioning (see Fig. 32.12, C).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of ASIN include other neoplasms within the squamous epithelium such as melanoma and primary or secondary Paget disease. Some ASIN-H lesions may demonstrate a pattern of pagetoid spread that can only be differentiated from Paget disease by immunohistochemistry (see Paget Disease of the Anus).144

Differentiating Reactive Changes or Immature Squamous Metaplasia from High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions

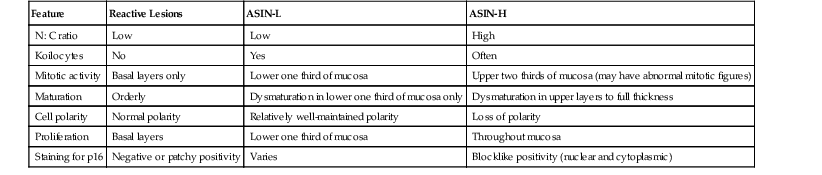

Distinguishing reactive changes from ASIN-L in biopsy material is fraught with high observer variability, and usually rests on deciding whether or not unequivocal HPV cytopathic effect is present (Table 32.3).145 Unfortunately, there are no reliable adjunctive pathologic methods to separate these two processes.

Table 32.3

Differential Diagnosis of Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Separation from Reactive Lesions

| Feature | Reactive Lesions | ASIN-L | ASIN-H |

| N : C ratio | Low | Low | High |

| Koilocytes | No | Yes | Often |

| Mitotic activity | Basal layers only | Lower one third of mucosa | Upper two thirds of mucosa (may have abnormal mitotic figures) |

| Maturation | Orderly | Dysmaturation in lower one third of mucosa only | Dysmaturation in upper layers to full thickness |

| Cell polarity | Normal polarity | Relatively well-maintained polarity | Loss of polarity |

| Proliferation | Basal layers | Lower one third of mucosa | Throughout mucosa |

| Staining for p16 | Negative or patchy positivity | Varies | Blocklike positivity (nuclear and cytoplasmic) |

ASIN-H, High-grade anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia; ASIN-L, low-grade anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia; N : C, nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio; p16, p16 protein.

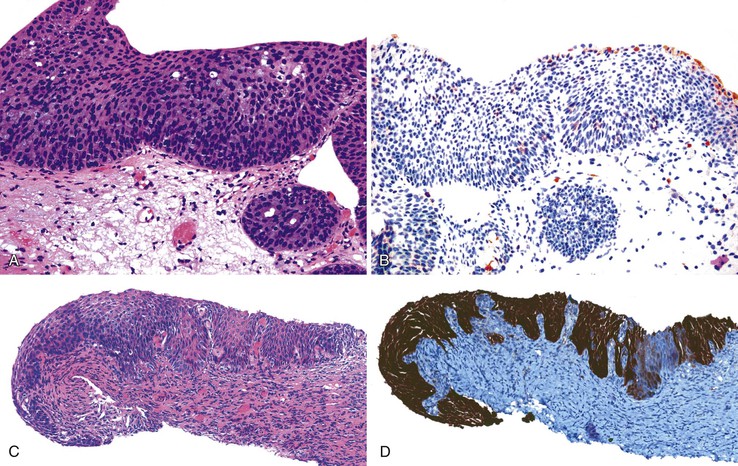

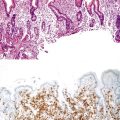

Separating reactive changes from ASIN-H, a precancerous lesion, is clinically important and more feasible (Fig. 32.13). Although reactive changes or immature squamous metaplasia and ASIN-H may show immature cells located beyond the basal layer, ASIN-H demonstrates a more disorganized or jumbled arrangement of the epithelium, and reactive processes tend to retain an orderly configuration of the squamous epithelial cells. Identification of inflammation or regular nuclei with open chromatin and prominent nucleoli favor a reactive process, whereas ASIN-H usually shows nuclear hyperchromasia and irregular nuclear contours.

When this differential is encountered, p16 immunohistochemistry often becomes necessary to separate reactive processes from ASIN-H. Weak and patchy immunoreactivity favors a non-neoplastic process, whereas diffuse, strong, and block positivity argues in favor of ASIN-H (Table 32.4).132 The latest recommendations argue against the use of multiple adjunctive immunohistochemical tests (e.g., p16 and Ki67) in the workup of a possible ASIN-H case.132 Evidence supports p16 as the best marker for ASIN-H, but Ki67146–148 and ProEx C (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ)149–151 may also be useful when difficulties with p16 arise.

Table 32.4

Use of P16 Immunohistochemistry in the Diagnosis of Anal Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia

| Diagnostic Problem | P16 Recommended? | Interpretation or Reasoning |

| Reactive versus ASIN-H | Yes | Block positive staining supports ASIN-H diagnosis |

| Diagnosis of ASIN-L versus ASIN-H (equivocal for ASIN-H) | Yes | Block positive staining supports ASIN-H diagnosis |

| Professional disagreement about histologic diagnosis (provided ASIN-H is in differential diagnosis) | Yes | Block positive staining supports ASIN-H diagnosis |

| Diagnosis of negative or reactive on histology | No | Staining may be confusing |

| Diagnosis of ASIN-L on histology | No | Staining may be confusing |

| Diagnosis of ASIN-H on histology | No | Staining may be confusing |

ASIN-H, High-grade anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia; ASIN-L, low-grade anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia; P16, p16 protein.

From Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1266-1297.

Distinguishing Low-Grade and High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions

In immunocompetent hosts, low-grade squamous lesions usually are transient and not precancerous, although this is often not the case in immunocompromised patients. Aside from the traditional morphologic features that separate ASIN-L from ASIN-H, the CAP and Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Project investigators identify at least two special circumstances for “bumping up” a lesion with the cytoarchitectural features of ASIN-L to ASIN-H: atypical mitotic figures or significant nuclear atypia beyond that expected in typical ASIN-L and thin ASINs, which are immature intraepithelial lesions less than 10 cells thick. As long as there are mitotic figures or cytologic features of ASIN above the basal layer, thin ASIN lesions should be considered ASIN-H. In both circumstances, a diffuse, strong, and blocklike positivity for p16 immunohistochemistry helps to confirm ASIN-H (Fig. 32.14).132

Differentiating High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions from Superficially Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Early invasion by SCC can be difficult to diagnose with certainty, particularly in the setting of a condyloma, because condylomata often have an undulating interface with the underlying stroma (Fig. 32.15). ASIN may colonize the anal ducts and glands, mimicking stromal invasion. It is best to maintain strict criteria for stromal invasion by a squamous carcinoma. Invasive carcinomas tend to arise in mucosa extensively involved by high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Several features support the diagnosis of invasion:

• Blurring of the epithelial-stromal interface with loss of the regular arrangement of the squamous basal cells152

The pathologist must be careful not to misinterpret artifacts or reactive changes such as those accompanying prior biopsy, intense stromal inflammation, or pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as evidence of invasive carcinoma.

Natural History and Treatment

Progression of ASIN largely depends on the immune status of the patient and extent of disease.153 Small series of immunosuppressed patients have found that as many as two thirds of cases progress from ASIN-L to ASIN-H within 2 years.141 After ASIN has developed, the rate of progression to carcinoma is uncertain, but some estimate that as many as 5% to 10% of patients will ultimately develop invasive disease.143 In one long-term surveillance study of 35 patients with ASIN-H, invasive carcinoma developed in 3 of 6 immunosuppressed patients (all with multifocal disease) in the follow-up period, but cancer did not develop in any of the other 3 patients.153 However, compared with some small observational studies, a meta-analysis found much lower progression rates; as few as 0.02% of cases progressed to invasive cancer per year.91

There are no well-established guidelines regarding appropriate screening for ASIN, even in at-risk populations, and groups such as the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons154 and the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland133 have opposite opinions regarding the benefit of screening for ASIN. Management guidelines range from watchful waiting to topical immunomodulatory or ablative therapies to surgical excision. Management of ASIN should probably be individually tailored, taking into account the patient’s symptoms and immune status and the size and focality of disease.133

When treatment is determined, the goal is to eradicate ASIN, prevent the development of anal carcinoma, and maintain anal function. The success of surgical resection is largely related to the extent of involvement and the ability to achieve a disease-free margin, although HIV status also seems to be an important factor.143 Unfortunately, many of these treatment modalities have been associated with high rates of recurrence, particularly in HIV-positive patients and those with extensive or multifocal disease.154

Perianal Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Many of the previously discussed clinical and pathologic principles for ASIN apply to perianal lesions. However, two perianal-specific terms are worthy of additional review: bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease. The use of these terms has been discouraged in anal pathology by some because they have engendered confusion with regard to their cutaneous counterparts. In practice, both conditions are considered to be HPV related in most cases and should be approached as such.

In the WHO classification, perianal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (PSIN) is synonymous with Bowen disease, which consists only of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or carcinoma in situ. Although the WHO has seemingly eliminated low-grade PSIN, low-grade lesions (PSIN-L), especially in the form of condylomata acuminata, do occur, although the “flat” PSIN-L lesions may be exceedingly difficult to reproducibly recognize, akin to the vulvar lesions.155 The clinicopathologically defined bowenoid papulosis (also PSIN-H) may continue to have diagnostic relevance because of its more indolent course.

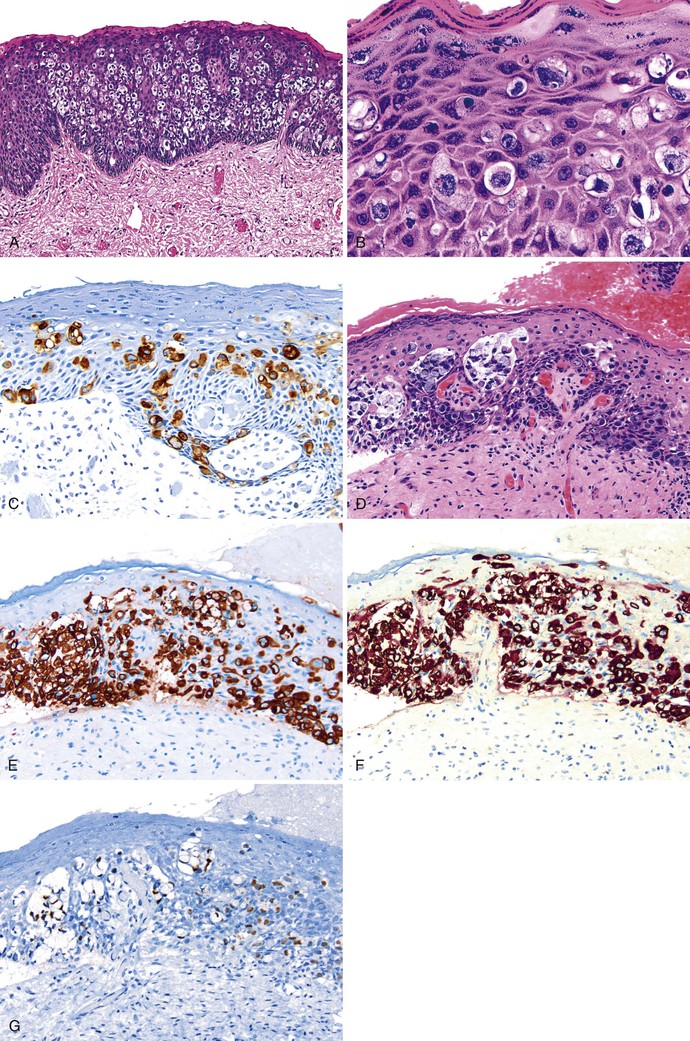

Bowen disease (PSIN-H) is rare in the perineal region.156 Bowen disease tends to involve the anal margin and adjacent perianal skin only as an extension of perineal Bowen disease. PSIN-H appears as erythematous, scaly plaques that may itch and burn; although in 25% of patients, it may be an incidental finding.157 Bowen disease mainly affects middle-aged to elderly individuals and has a known association with other primary internal and extracutaneous malignancies. In the skin, Bowen disease is associated with sun exposure, whereas in the anal region, high-risk HPV subtypes have been detected.

Bowen disease appears as areas of firm, irregular-bordered, reddish-brown plaques with a scaly surface, and some patients may have ulceration. Histologic examination of these plaques reveals a striking full-thickness disorganization of the squamous epithelium, characterized by abundant, large, atypical cells and loss of orderly surface maturation on a background acanthosis, hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis, and particularly dyskeratosis (Fig. 32.16). Mitotic figures occur frequently and can be seen at all levels of the epithelium along with multinucleated cells and koilocytes. Accessory skin structures are often incorporated into the lesion as it spreads laterally throughout the epidermis. The superficial dermis underlying the neoplastic epithelium often contains a chronic inflammatory infiltrate.

Bowen disease and bowenoid papulosis are two forms of PSIN-H and cannot be reliably separated based on histology alone. Bowenoid papulosis consists of small papules, whereas Bowen disease is composed of large and often multifocal plaques. Bowenoid papulosis also shows clearly demarcated borders from the surrounding normal skin and usually does not involve the skin appendages. Bowen disease often requires formal histologic mapping to discern the extent of disease.156,158 Bowen disease is also included in the differential diagnosis of Paget disease and melanoma. Differentiation of Bowen disease from these entities is discussed later.

Bowen disease of the anus is a chronic and slowly progressive condition that tends to spread intradermally. It is prone to local recurrence after wide excision if disease-free (negative) margins are not achieved.156,157 Even when negative margins are attained, up to 25% of patients have recurrent disease within 3 to 4 years. In a few patients with Bowen disease who are not treated adequately by wide local excision, transformation to invasive disease may occur.157

In the past, the standard form of treatment of Bowen disease was histologic mapping followed by wide local excision to achieve negative margins.156,158 However, despite preoperative mapping, as many as 63% of patients had recurrences within 1 year after wide local excision.159 Topical 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod has been effective for patients with extensive disease.160,161

Bowenoid papulosis was initially described as a lesion of the genitalia of young adults, most often diagnosed in the third decade of life. In addition to its common occurrence on the penis and vulva, anal lesions may occur.30 Clinically, bowenoid papulosis is characterized by one or more small, reddish-brown papules in the anogenital region that persist for a few weeks to several years.162 Most patients are asymptomatic, although some complain of pruritus associated with areas of involved perianal skin.

Bowenoid papulosis appears as slightly raised, firm, red to brown papules that may be scaly and are usually located on the perianal skin. Classically, these lesions are sharply circumscribed and more easily treated by excision. The papules rarely exceed a few millimeters in diameter. Despite their rather benign gross appearance, the histology of bowenoid papulosis is similar to conventional PSIN-H or Bowen disease.162 The squamous epithelium is typically acanthotic, and the surface of the epithelium is hyperkeratotic. At higher magnification, the epithelium shows cytologic atypia and disordered maturation, with scattered dyskeratotic and mitotic cells seen throughout the thickness of the epithelium (see Fig. 32.16). Parakeratosis and hypergranulosis may also be identified.

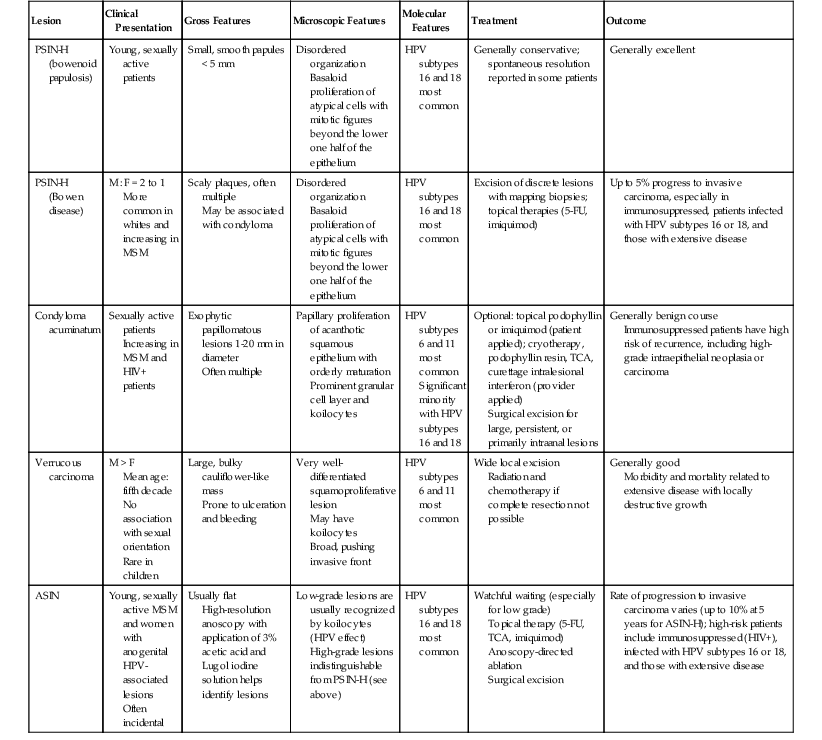

Based purely on histology, small or partial biopsies of bowenoid papulosis cannot be reliably separated from Bowen disease. When a pathologist encounters PSIN-H histology in the setting of a young patient with small anogenital papules, a note documenting the possibility of bowenoid papulosis may be indicated. If the entire lesion is excised and its small size is confirmed, the pathologist can more confidently consider the lesion as a bowenoid papulosis variant of PSIN-H. The distinction is important because clinical follow-up of bowenoid papulosis suggests it is usually a benign condition. Most cases resolve spontaneously without treatment, although in some patients, it is chronic and slowly progressive. Squamous lesions that may cause diagnostic confusion with or progress to invasive SCC are summarized in Table 32.5.

Table 32.5

Clinical and Pathologic Features of Noninvasive Human Papilloma Virus–Associated Anal Squamous Lesions

| Lesion | Clinical Presentation | Gross Features | Microscopic Features | Molecular Features | Treatment | Outcome |

| PSIN-H (bowenoid papulosis) | Young, sexually active patients | Small, smooth papules < 5 mm | Disordered organization Basaloid proliferation of atypical cells with mitotic figures beyond the lower one half of the epithelium |

HPV subtypes 16 and 18 most common | Generally conservative; spontaneous resolution reported in some patients | Generally excellent |

| PSIN-H (Bowen disease) | M : F = 2 to 1 More common in whites and increasing in MSM |

Scaly plaques, often multiple May be associated with condyloma |

Disordered organization Basaloid proliferation of atypical cells with mitotic figures beyond the lower one half of the epithelium |

HPV subtypes 16 and 18 most common | Excision of discrete lesions with mapping biopsies; topical therapies (5-FU, imiquimod) | Up to 5% progress to invasive carcinoma, especially in immunosuppressed, patients infected with HPV subtypes 16 or 18, and those with extensive disease |

| Condyloma acuminatum | Sexually active patients Increasing in MSM and HIV+ patients |

Exophytic papillomatous lesions 1-20 mm in diameter Often multiple |

Papillary proliferation of acanthotic squamous epithelium with orderly maturation Prominent granular cell layer and koilocytes |

HPV subtypes 6 and 11 most common Significant minority with HPV subtypes 16 and 18 |

Optional: topical podophyllin or imiquimod (patient applied); cryotherapy, podophyllin resin, TCA, curettage intralesional interferon (provider applied) Surgical excision for large, persistent, or primarily intraanal lesions |

Generally benign course Immunosuppressed patients have high risk of recurrence, including high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or carcinoma |

| Verrucous carcinoma | M > F Mean age: fifth decade No association with sexual orientation Rare in children |

Large, bulky cauliflower-like mass Prone to ulceration and bleeding |

Very well-differentiated squamoproliferative lesion May have koilocytes Broad, pushing invasive front |

HPV subtypes 6 and 11 most common | Wide local excision Radiation and chemotherapy if complete resection not possible |

Generally good Morbidity and mortality related to extensive disease with locally destructive growth |

| ASIN | Young, sexually active MSM and women with anogenital HPV-associated lesions Often incidental |

Usually flat High-resolution anoscopy with application of 3% acetic acid and Lugol iodine solution helps identify lesions |

Low-grade lesions are usually recognized by koilocytes (HPV effect) High-grade lesions indistinguishable from PSIN-H (see above) |

HPV subtypes 16 and 18 most common | Watchful waiting (especially for low grade) Topical therapy (5-FU, TCA, imiquimod) Anoscopy-directed ablation Surgical excision |

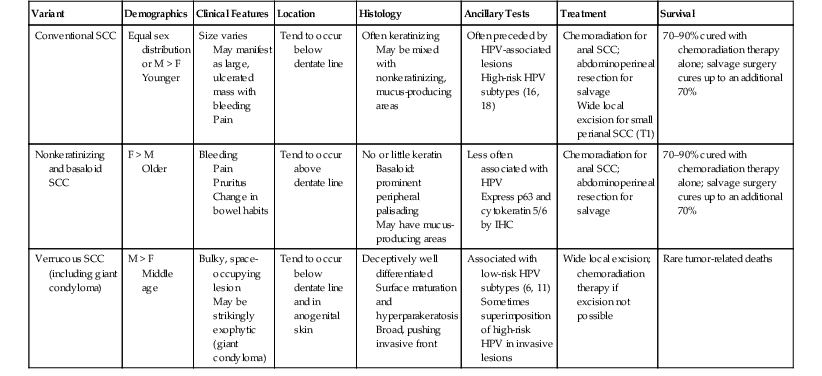

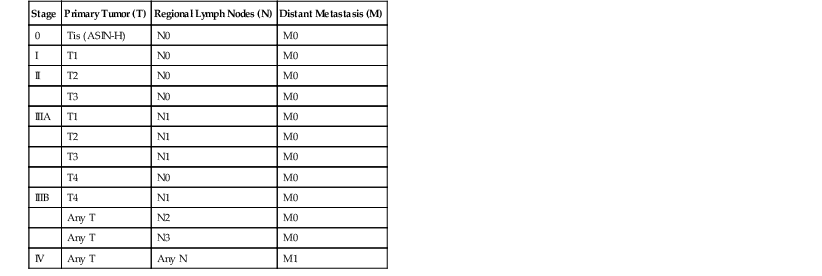

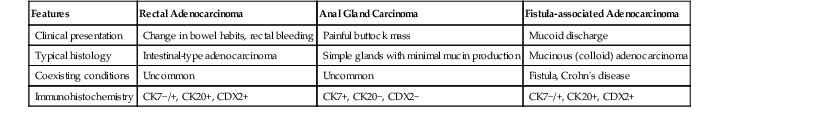

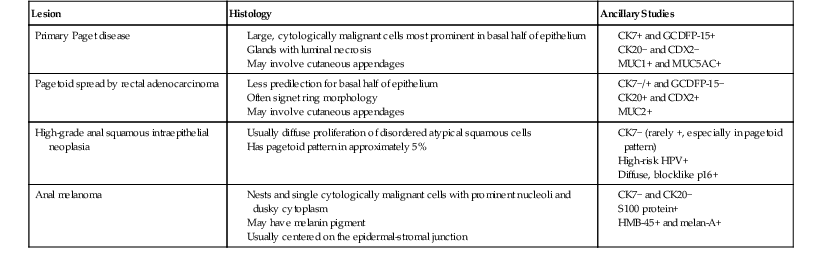

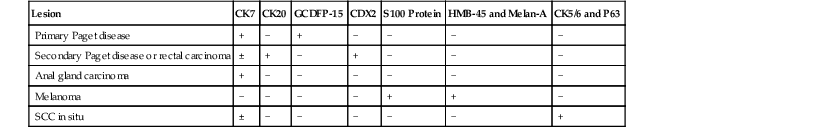

Rate of progression to invasive carcinoma varies (up to 10% at 5 years for ASIN-H); high-risk patients include immunosuppressed (HIV+), infected with HPV subtypes 16 or 18, and those with extensive disease |