Inflammatory and infectious disorders of the brain

JUDITH A. DEWANE, PT, DSc, NCS

After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to:

1. Identify and comprehend the terminology for classifying different types of inflammatory and infectious disorders within the brain.

2. Discuss the range of neurological sequelae that occur.

3. Discuss the components of the comprehensive evaluation process and their interrelationships.

4. Structure the examination process to gather the information required to generate an appropriate plan of care.

Overview of inflammatory disorders in the brain

Categorization of inflammatory disorders

The inflammatory process may be a localized, circumscribed collection of pus; may involve primarily the leptomeninges; may involve the brain substance; or may involve both the meninges and the brain substance. The infecting agents may be bacteria, viruses, prions, fungi, protozoa, or parasites. The most common agents producing meningitis are bacterial; the most common agents producing encephalitis are viral. However, bacterial encephalitis and viral meningitis also are disease entities. The following overview of the inflammatory processes within the brain is organized based on the anatomical location of the infection. More comprehensive discussions based on specific infecting organisms can be found in the references at the end of the chapter.1 The site of the infection will determine the signs and symptoms of the CNS infections, whereas the infecting organism determines the prognosis, including the time course and severity of the problems.2

Brain abscess

The site and size of the abscess influence the initial symptoms. Evidence of increased intracranial pressure, a focal neurological deficit, and fever are described as the classic presenting triad.3 However, the classic triad occurs in less than 50% of patients.4 Most individuals experience an alteration of consciousness. In 47% of the cases, the frontal, parietal, or temporal lobe is involved.4,5 Medical management of the abscess typically consists of antibiotic therapy (depending on the infecting agent and size and site of the abscess) and, often, surgical aspiration or excision. Bharucha and colleagues3 describe neurological sequelae in 25% to 50% of the survivors, with 30% to 50% having persistent seizures, 15% to 30% having hemiparesis, and 10% to 20% having disorders of speech or language.

Meningitis

Bacterial meningitis

Clinical problems.

The diagnostic categorization of meningitis depends on the infecting agent (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae meningitis, Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, and viral meningitis) and on the acute or chronic nature of the meningitis (acute, subacute, or chronic meningitis). The term acute bacterial meningitis denotes infections caused by aerobic bacteria (both gram-positive and gram-negative).5,6 The most common infecting organism producing acute bacterial meningitis varies according to the age of the population. During the neonatal period and in the older adult, infections by gram-negative enterobacilli, especially Escherichia coli, and group B streptococci occur most frequently. Typical causative agents in children include H. influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, and S. pneumoniae.7 S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, and H. influenzae are the most common causes of community-acquired meningitis.5,7,8 Individuals with a condition such as sickle cell anemia, alcoholism, or diabetes mellitus and individuals who are immunosuppressed are at increased risk.1,9 Meningococci have been implicated in meningitis that strikes young children most often but can also infect adolescents and young adults. Freshman who live in dormitories are almost four times more likely to get meningitis than other college students.

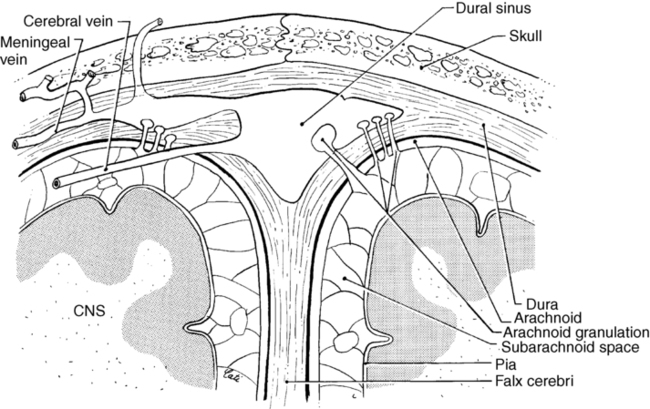

The circulation of CSF spreads the infecting organism through the ventricular system and the subarachnoid spaces (Figure 26-1). The pia and arachnoid maters become acutely inflamed, and as part of the inflammatory response, a purulent exudate forms in the subarachnoid space. The exudate may undergo organization, resulting in an obstruction of the foramen of Monro, the aqueduct of Sylvius, or the exit foramen of the fourth ventricle. The supracortical subarachnoid spaces proximal to the arachnoid villi may be obliterated, resulting in a noncommunicating or obstructive hydrocephalus caused by the accumulation of CSF. As the CSF accumulates, the intracranial pressure rises. The increased intracranial pressure produces venous obstruction, precipitating a further increase in the intracranial pressure. The rise in the CSF pressure compromises the cerebral blood flow, which activates reflex mechanisms to counteract the decreased cerebral blood flow by raising the systemic blood pressure. An increased systemic blood pressure accompanies increased CSF pressure.

Clinical features of acute bacterial meningitis include fever, severe headache, altered consciousness, convulsions (particularly in children), and nuchal rigidity. Nuchal rigidity is indicative of an irritative lesion of the subarachnoid space. Signs of meningeal irritation are painful cervical flexion, the Kernig sign, the Brudzinski sign, and the jolt sign.10 Cervical flexion is painful because it stretches the inflamed meninges, nerve roots, and spinal cord. The pain triggers a reflex spasm of the neck extensors to splint the area against further cervical flexion; however, cervical rotation and extension movements remain relatively free.

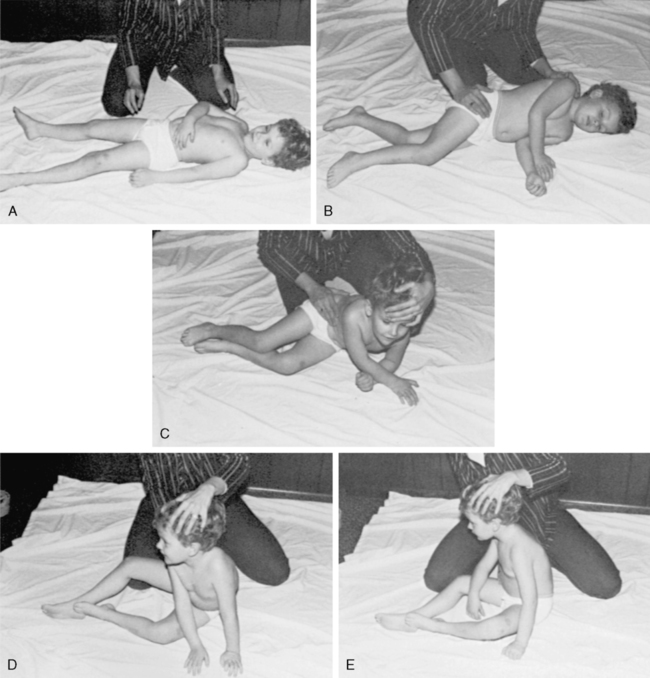

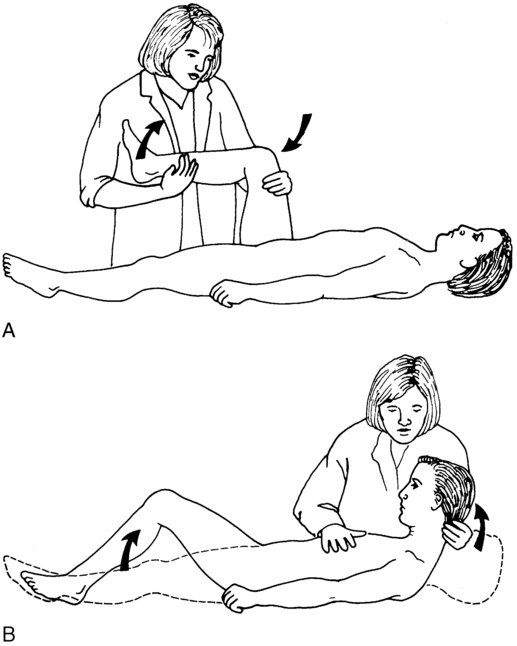

The Kernig sign refers to a test performed with the client supine in which the thigh is flexed on the abdomen and the knee extended (Figure 26-2, A). Complaints of lumbar or posterior thigh pain indicate a positive test result.10 This movement pulls on the sciatic nerve, which pulls on the covering of the spinal cord, causing pain in the presence of meningeal irritation. The same results are achieved with passive hip flexion with the knee remaining in extension. This is the same procedure described by Hoppenfeld11 as the straight leg raising test for determining pathology of the sciatic nerve or tightness of the hamstrings. Passive hip flexion with knee extension can be painful because of meningeal irritation, spinal root impingement, sciatic nerve irritation, or hamstring tightness. The Brudzinski sign refers to the flexion of the hips and knees elicited when cervical flexion is performed10 (see Figure 26-2, B). These signs will not be present in the deeply comatose client who has decreased muscle tone and absence of muscle reflexes. The signs may also be absent in the infant or elderly patient. Finally, the jolt test, which has the patient turn his or her head from side to side quickly (two to three rotations per second), has a positive result if the maneuver worsens the patient’s headache.10

A, Kernig sign. B, Brudzinski sign.

A, Kernig sign. B, Brudzinski sign.Potential neurological sequelae.

Even with optimal antimicrobial therapy, bacterial meningitis continues to have a finite mortality rate, which varies with the infecting organism, age of the individual, and time lapse to initiation of treatment, and has the potential for marked neurological morbidity. Neurological sequelae occur in 20% to 50% of the cases.1,9 Bacterial meningitis is considered a medical emergency; delays in initiation of antibacterial therapy increase the risk of complications and permanent neurological dysfunction.1,9

Reports of the long-term outcome of individuals with bacterial meningitis indicate that up to 20% have long-term neurological sequelae.1,5 The sequelae may be the result of the acute infectious pathological condition or subacute or chronic pathological changes. The acute infectious pathological condition could result in sequelae such as inflammatory or vascular involvement of the cranial nerves or thrombosis of the meningeal veins. Cranial nerve palsies, especially sensorineural hearing loss, are common complications. The risk of an acute ischemic stroke is greatest during the first 5 days.9 Weeks to months after treatment, subacute or chronic pathological changes may develop, such as communicating hydrocephalus, which manifests as difficulties with gait, mental status changes, and incontinence.10,12 Approximately 5% of the survivors will have weakness and spasticity.6 Focal cerebral signs that may occur either early or late in the course of bacterial meningitis include hemiparesis, ataxia, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, and gaze preference.1,13 Cognitive slowness has been found in 27% of clients after pneumococcal meningitis, even with good recovery as documented by a Glasgow Outcome Scale score of 5.14

Aseptic meningitis.

Aseptic meningitis refers to a nonpurulent inflammatory process confined to the meninges and choroid plexus, usually caused by contamination of the CSF with a viral agent, although other agents can trigger the reactions. The symptoms are similar to those of acute bacterial meningitis but typically are less severe. The individual may be irritable and lethargic and complain of a headache, but cerebral function remains normal unless unusual complications occur.5,15 Aseptic meningitis of a viral origin usually causes a benign and relatively short course of illness.16,17

A variety of neurotropic viruses can produce aseptic (viral) meningitis. The enteroviruses (echoviruses and the Coxsackie viruses), herpesviruses, and HIV are the most common causes.5,7,18 The primary nonviral causes of aseptic meningitis are Lyme Borrelia and Leptospira.19 The diagnosis of this type of aseptic meningitis may be established by isolation of the infecting agent within the CSF or by other techniques. The glucose level of the CSF in bacterial meningitis is usually depressed; however, the glucose level in viral meningitis is normal.2

Encephalitis

Clinical problems.

The pathological condition includes destruction or damage to neurons and glial cells resulting from invasion of the cells by the virus, the presence of intranuclear inclusion bodies, edema, and inflammation of the brain and spinal cord. Perivascular cuffing by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lymphocytes may occur, as well as angiitis of small blood vessels. Widespread destruction of the white matter by the inflammatory process and by thrombosis of the perforating vessels can occur. Increased intracranial pressure, which can result from the cerebral edema and vascular damage, presents the potential for a transtentorial herniation. The likelihood of residual impairment of neurological functions depends on the infecting viral agent. Patients with mumps meningoencephalitis have an excellent prognosis, whereas 55% of the individuals with herpes simplex encephalitis treated with acyclovir have some neurological sequelae.6 Because of the slow recovery of injured brain tissue, even in patients who recover completely, return to normal function may take months.20

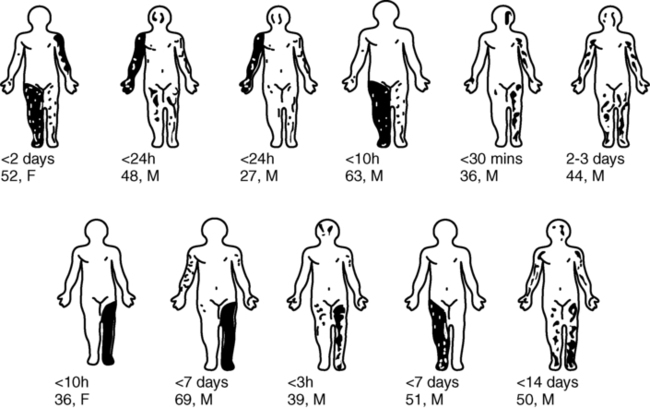

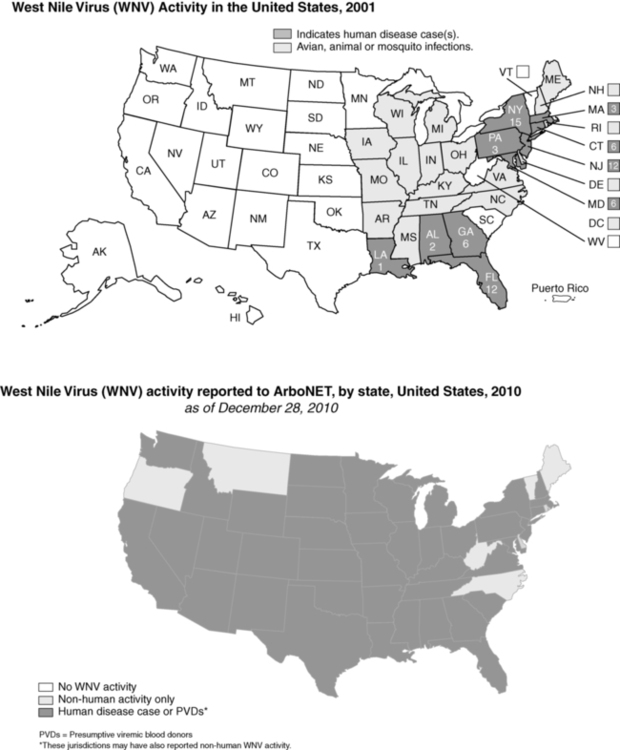

Plum and Posner21 discuss viral encephalitis in terms of five pathological syndromes. Acute viral encephalitis is a primary or exclusively CNS infection. An example would be herpes simplex encephalitis, in which the virus shows a partiality for the gray matter of the temporal lobe, insula, cingulate gyrus, and inferior frontal lobe. Other examples are the mosquito-borne viruses, such as the St. Louis encephalitis, California virus encephalitis, and most recently the West Nile virus (WNV). From 1999 to 2005 in the United States, the incidence of infection from the WNV has increased from 62 cases to 3000 cases.22 Currently all states have some level of WNV activity, and only four states are without human cases (Figure 26-3). The majority (80%) of people infected by the WNV will be asymptomatic; of the remaining people infected, less than 1% will develop severe illness.23 Risk of neuroinvasive disease from WNV is 40%; neuroinvasive disease involves meningitis, encephalitis, or poliomyelitis, with wide variety in clinical presentation (Figure 26-4).24 Parainfectious encephalomyelitis is associated with viral infections such as measles, mumps, or varicella. Acute toxic encephalopathy denotes encephalitis that occurs during the course of a systemic infection with a common virus. The clinical symptoms are produced by the cerebral edema in acute toxic encephalopathy, which results in increased intracranial pressure and the risk of transtentorial herniation. Reye syndrome is an example. Global neurological signs, such as hemiplegia and aphasia, are usually present, rather than focal signs. The clinical symptoms of the previous three syndromes may be similar. Specific diagnosis may be established only by biopsy or autopsy.

West Nile virus (WNV) activity in the United States. (From www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/Mapsactivity/surv&control10MapsAnybyState.htm.)

West Nile virus (WNV) activity in the United States. (From www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/Mapsactivity/surv&control10MapsAnybyState.htm.)Progressive viral infections occur from common viruses invading susceptible individuals, such as those who are immunosuppressed or during the perinatal to early childhood period. Slow, progressive destruction of the CNS occurs, as in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. The final category of encephalitis syndromes consists of “slow virus” infections by unconventional agents (the prion diseases) that produce progressive dementing diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and kuru.25

Medical management.

The medical management of virally induced encephalitis has been, and with many infecting agents remains, primarily symptomatic. In some cases, intensive, aggressive care is necessary to sustain life. Pharmacological interventions are available to treat some viral infections, such as herpes encephalitis. The probability of neurological sequelae differs according to the infecting agent. Aggressive management of increased intracranial pressure is required because persistently elevated intracranial pressure is associated with poor outcome.1,26 Further information concerning the clinical features, medical management, and potential for neurological sequelae of a specific type of encephalitis should be sought in the literature based on the infecting agent.

Clinical picture of the individual with inflammatory disorders of the brain

An individual within the acute phase of meningitis or encephalitis or with residual neurologic dysfunction from these disorders may demonstrate signs and symptoms similar to those of generalized brain trauma, tumor disorder, or other identified abnormal neurological state. The variability in the clinical picture is reflected in the inclusion of the category “infectious diseases that affect the central nervous system” in the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice.27 Practice patterns for physical therapists that apply to this population include the following:

5C: Impaired Motor Function and Sensory Integrity Associated with Nonprogressive Disorders of the Central Nervous System—Congenital Origin or Acquired in Infancy or Childhood

5D: Impaired Motor Function and Sensory Integrity Associated with Nonprogressive Disorders of the Central Nervous System—Acquired in Adolescence or Adulthood

5I: Impaired Arousal, Range of Motion, and Motor Control Associated with Coma, Near Coma, or Vegetative State

5A: Primary Prevention/Risk Reduction for Loss of Balance and Falling

Examination and evaluation process

Observation of current functional status

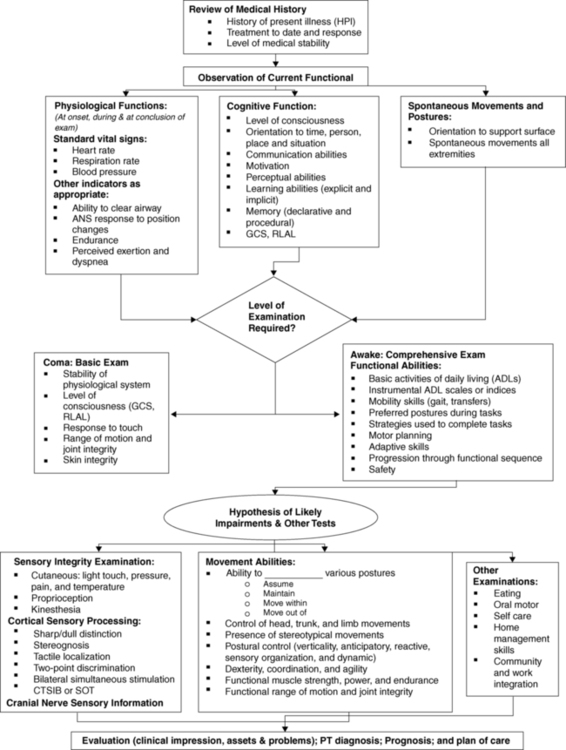

The following discussion of the specific considerations within the examination process does not necessarily represent the temporal sequence to be used during the data collection process. As different items are discussed, suggestions for potential combinations of items will be made. The sequence of the process is best determined by the interaction of therapist and client. Figure 26-5 outlines the components that should be considered during the evaluation process and provides a synopsis of the following discussion.

Flow chart of the evaluation process.

Flow chart of the evaluation process.Evaluation of cognitive status

Acute bacterial meningitis and various forms of viral encephalitis may result in changes in the client’s level of consciousness. Consciousness is a state of awareness of one’s self and one’s environment.21 Coma can be defined as a state in which one does not open the eyes, obey commands, or utter recognizable words.28 The individual does not respond to external stimuli or to internal needs. The term vegetative state is sometimes used to indicate the status of individuals who open their eyes and display a sleep-wake cycle but who do not obey commands or utter recognizable words. DeMeyer29 presents a succinct description of the neuroanatomy of consciousness and the neurological examination of the unconscious patient. Plum and Posner21 also provide extensive information in this area.

Several scales have been developed to provide objective guidelines to assess alterations in the state of consciousness. The Glasgow Coma Scale28 assesses three independent items: eye opening, motor performance, and verbal performance. The scale yields a figure from 3 (lowest) to 15 (highest) that can be used to indicate changes in the individual’s state of consciousness. The evaluation format is simple, and the scale demonstrates both interrater and intrarater reliability. Refer to Box 24-4 for the specific scale. The Rancho Los Amigos scale assesses level of consciousness and behavior.28 The therapist can use assessment tools such as the Glasgow Coma Scale and the companion Glasgow Outcome Scale to determine if the intervention program has resulted in any recordable changes in the client’s level of consciousness. Ideally, the client with decreased levels of consciousness will be monitored at consistent intervals to determine changes in status. Any carryover or delayed effects of the intervention could then be noted. The record of the client’s level of consciousness might also display a pattern of peak awareness at a particular point in the day. Scheduling an intervention session during the client’s peak awareness time may maximize the benefit of the therapy.

Deficits in cognition may be evident as problems in the area of explicit (declarative) or implicit (procedural) learning. Explicit learning is used in the acquisition of knowledge that is consciously recalled. This is information that can be verbalized in declarative sentences, such as the sequential listing of the steps in a movement sequence. Implicit or procedural learning is used in the process of acquiring movement sequences that are performed automatically without conscious attention to the performance. Procedural learning occurs through repetitions of the movement task (refer to Chapter 4). Because explicit and implicit learning use different neuroanatomical circuits, implicit learning can occur in individuals with deficits in the components underlying explicit learning (awareness, attention, higher-order cognitive processes) (refer to Chapter 5 for additional information regarding implicit and explicit learning).

Examination of functional abilities

Another aspect of the evaluation process that can be integrated in the observations of movement abilities is identification of perceptual deficits. Aspects of the client’s motor performance can provide indications for detailed perceptual testing to classify the deficits. This testing should be conducted by the health care team member qualified in the area of perceptual testing. During the general evaluation procedures, the therapist can screen the client for signs of perceptual deficits. Clients’ abilities to cross their midlines with their upper extremities can be demonstrated in movement sequences, such as moving from the supine to the side-sitting to the sitting position (Figure 26-6). The quality of the integration of information from the two sides of the body can be indicated by the symmetry or asymmetry of posture in positions that should be symmetrical. The therapist may suspect that the client has a deficit in body awareness or body image by the poor quality of movement patterns that are within the motor capability of the individual. Spontaneous comments by the client as to how he or she feels when moving (“my leg feels so heavy”) also add to the therapist’s assessment of the client’s body image. Problems with verticality can be seen with the client who lists to one side when in an upright posture. When the therapist corrects the list to a vertical posture, clients may express that they now feel that they are leaning to one side. Individuals who cannot appropriately relate their positions to the position of objects in their environments may have a figure-ground deficit or a problem with the concept of their position in space. When approaching stairs, these clients may fail to step up or may attempt to step up too soon. These examples should provide an indication of the observations that can indicate the need for detailed perceptual testing.

Evaluation of sensory channel integrity and processing

Central processing and integration of sensory information as it affects postural control can be examined using the Clinical Test of Sensory Integration and Balance (CTSIB)30 or with computerized dynamic posturography using the Sensory Organization Test (SOT). With both tests, the effectiveness of using vision or somatosensory or vestibular sensation at the appropriate time (sensory weighting) and changing from one sensory system to the other is examined.

The complex functions of the vestibular system can be assessed through a variety of avenues such as the Ayres Post-Rotatory Nystagmus Test,31,32 the SOT, and tests of the vestibular ocular reflex (head-thrust test, head-shaking test, and test of dynamic visual acuity [DVA]), and are discussed in detail elsewhere in this text. It is important to examine the vestibular influence in both postural control and gaze stability. The integrity of the connections underlying a vestibularly induced nystagmus response is assessed by physicians through the caloric test (warm and cold water or air introduced into the ear channel to induce nystagmus). The effect of rapid linear accelerations and decelerations can be evaluated as potential activating mechanisms increasing the level of consciousness or level of muscle activity. An example is the Dynamic Gait Index, a functional test that incorporates changes in speed and head movements during walking.33 Slow, rhythmical reversals of linear movements may have a calming effect on the client’s behavior or level of muscle activation. Linear movements in all planes and diagonals should be explored.

Prognosing and goal setting

The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice views outcomes in relationship to “minimization of functional limitations, optimization of health status, prevention of disability, and optimization of patient/client satisfaction,” whereas goals “relate to the remediation (to the extent possible) of impairments.”27 The breadth of acceptance of these definitions with the neurorehabilitation professions remains to be determined. These definitions at least give professionals a place to start communicating with consistency. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model of the World Health Organization provides similar definitions, with the focus being client centered.

Measurable, interim objectives should be established in relation to the outcome statements. To determine if the objective has been achieved, the objective should be measurable—either in terms of producing a numerical indicator of performance, such as time span, number of repetitions, distance covered, or accuracy of performance, or in terms of a precise description of the target motor behavior. The appropriate objective indicator must be carefully selected. Performing a movement more quickly may indicate that the individual is performing it with more normal control and therefore greater ease of movement, or it may indicate that the individual has become more skilled in using an abnormal pattern based on inappropriate muscle activation. If it is not appropriate to formulate the objective in terms of a numerical indicator, the objective can be formulated in terms of an observable behavior. The therapist can precisely describe body segment movements based on the component method of movement analysis presented by VanSant.34 For example, the task of coming to standing from supine can be described in terms of the upper-extremity component, axial component, and lower-extremity component.35 Formulation of an appropriate short-term objective could specify use of the upper extremities in a push-and-reach pattern during the task of coming to standing from supine. The interim objectives should be constructed so that observing the client’s behavior will allow the therapist to state whether the criteria of the short-term objective were achieved. Table 26-1 gives an example of some components of short-term objectives leading to mastery of functional activities in sitting.

TABLE 26-1

EXAMPLES OF SHORT-TERM OBJECTIVES RELATING TO MASTERY OF FUNCTIONAL ACTIVITIES IN SITTING*

| CONDITION VARIABLES† | ACTIVITY | CRITERIA | |

*Outcome: The client will master functional activities in sitting. Short-term objective: Select one phrase from each column.

†Therapist needs to consider all aspects of each variable (i.e., 1—a, b, c, d, e; 2—a, b, c, d, e; 3—a, b, c, d, e).

General goals for the intervention process

Goal 1: Postural control is optimized as demonstrated by the ability to maintain a position against gravity and the ability to automatically adjust before and continuously during movement.

Goal 2: Selective, voluntary movement patterns within functional activities are optimized.

Goal 3: Performance of functional activities is enhanced.

Goal 4: Integration of sensory information is fostered.

Goal 5: Cognitive status and psychosocial responses are optimized.

General therapeutic intervention procedures in relation to intervention goals

Postural control is optimized as demonstrated by the ability to maintain a position against gravity and the ability to adjust automatically before and continuously during movement.

Postural control is optimized as demonstrated by the ability to maintain a position against gravity and the ability to adjust automatically before and continuously during movement.

Optimal postural control is defined by two elements. The client should have the ability to maintain a vertical orientation with regard to gravity and should be able to maintain balance in the presence of both internal and external perturbations. Automatic adjustments in the postural set should occur in anticipation of and continuously during movements (internal perturbations). Both elements should be performed with minimal physical or cognitive effort on the part of the client. Horak describes five components of normal postural control, including vertical orientation; anticipatory, reactive, sensory organization; and dynamic postural control for gait.36 By looking at the subsets of postural control, interventions can be designed to specifically match the impairment (Table 26-2).

TABLE 26-2

INTERVENTIONS FOR POSTURAL CONTROL PROBLEMS

| POSTURAL CONTROL PROBLEM | POSSIBLE INTERVENTIONS |

| Malalignment and verticality problems | Augment sensory feedback: |

Hold on and slow down (lessen the need for anticipatory control—substitution)

Mental rehearsal (weight shift, then move)

Practice limb movements where balance must be controlled (start slow and get faster)

Interactions with the environment with a static base of support, such as reaching up in a cupboard, opening a door, opening a drawer, lifting a suitcase, lifting a bag of groceries, wearing a backpack

Interactions with the environment with a static base of support, such as reaching up in a cupboard, opening a door, opening a drawer, lifting a suitcase, lifting a bag of groceries, wearing a backpack

Interactions with the environment with a dynamic base of support (stepping up a step, kicking a ball, stepping over an object, stepping around an object, changing the pitch of the surface—inclines)

Interactions with the environment with a dynamic base of support (stepping up a step, kicking a ball, stepping over an object, stepping around an object, changing the pitch of the surface—inclines)

Practice rapid limb movements where balance must be controlled (opening a door, opening a drawer, lifting a briefcase, lifting a bag of groceries, lifting a suitcase, wearing a backpack). Practice order:

Practice the anticipatory postural adjustment

Practice the anticipatory postural adjustment

Practice the focal action while supported

Practice the focal action while supported

Combine the anticipatory postural adjustment with the focal action unsupported (slow to fast)

Combine the anticipatory postural adjustment with the focal action unsupported (slow to fast)

Practice varying similar tasks (predictable to unpredictable)

Practice varying similar tasks (predictable to unpredictable)

Example: After the patient is doing better on a lifting task involving one object, he or she can work to be successful with several objects of different weights; first cognitively solve what must change for achievement of success in lifting one object versus another; then much repetition of alternating one object versus another; and eventually, work with a variety of objects in a varied pattern.

Work to regain balance strategies (ankle, hip, and stepping)

Remediate any biomechanical issues that affect use of balance strategies

Begin with self-perturbation and progress to reacting to external perturbations

Need to learn to match the magnitude and direction of perturbation

Physioballs, T-stools, tilt boards, reaching, weight shifting

Alter the sensory contexts (e.g., resisted walking)

Walking and reading signs right and left

Carrying objects and looking at items carried

Walking with quick stops (predictable distances and reactive)

Practice falling without injury and getting up; practice slips and trips

Anticipatory postural control involves the postural preset, which positions the trunk to allow skilled use of the extremities without loss of balance. It requires the client to recognize the situation and the likely destabilizing force that will result, and posturally preset so destabilizing will not occur. The process requires memory and the ability to recognize the critical environmental and task cues. Interventions focus on practicing both the postural adjustment and the focal action before the two components are combined. Table 26-2 also has suggested interventions for reactive, sensory integrative, and dynamic balance in gait problems. Postural control is affected as well by biomechanical constraints, such as tonal abnormalities.

The therapist must address the hypertonicity influencing postural control as a generalized problem before demanding selective voluntary activation of specific muscle groups. Vestibular input that is slow and rhythmical may promote a generalized relaxation of skeletal muscle activity. In some clients, the trunk remains “stiff” in movement sequences in which a segmental response between the upper and lower trunk should occur. Repetitions of rhythmical movements in side lying in which the therapist gently and progressively stretches the client’s pelvis in one direction around the body axis while moving the shoulder girdle in the opposite direction and then reverses the movement may effectively alter the biomechanical and neurological contributions to the stiffness (Figure 26-7).

If the client is sufficiently alert that attending to and understanding directions is a possibility, the therapist should direct the person to focus on the effects of the movement responses rather than focusing attention on the movement of the body.37 As the person begins to appreciate the consequences of what is transpiring, he or she should be asked to assist in maintaining the changes that promote the more skillful movement response. Unless otherwise indicated by the client’s status, interventions must actively involve the individual in the process of planning, initiating, completing, and evaluating the movement. Although the therapist may manipulate the environment (internal and external) in which the response is made, the client must be an active participant for learning to occur.

Clients who exhibit stereotypical posturing of the upper extremity with a restricted repertoire of available movement patterns require intervention to change the initial position of the extremity before movements are attempted. The influence of the spasticity that interferes with the repositioning of the extremity can be reduced by applying approximation through the long axis of the extremity. Preferably, the therapist’s manual contacts for the application of the approximation force are on the weight-bearing surfaces of the hand. If the flexed position of the wrist prohibits application of the force to the heel of the palm, the approximation can be applied gradually through the fisted hand. As the resistance to passive movement diminishes, the wrist can be moved toward the neutral position so that the therapist can apply the approximation through the heel of the palm (Figure 26-8). The therapist is moving the extremity toward an alternative resting position so that a new movement sequence can be attempted. It is important to use an intervention technique, such as approximation, to reduce the level of spasticity before passive movement is attempted so that a more appropriate position can be assumed without inappropriately stretching the spastic muscles.

The client is asked to assist the therapist with the movement, with the person being cued to do so with a minimum of effort. Too often, clients attempt to make a selective movement through a massive effort and overactivation of the muscle groups, which compounds the underlying spasticity. Clients should be encouraged to make easy, effortless movements—those they are instructed to perform with reduced effort so that they can relearn selective activation of motor units rather than mass firing patterns. Working “harder” often creates additional impairments versus increasing normal functional movement responses. It is critical that the movements requested relate to a functional activity or skill. Research suggests that skilled movements require attention and therefore motivation. Shaping the activity to both interest the client and afford some level of success is important.33

The flow of a movement pattern may be disrupted by problems categorized as incoordination. The origin of the coordination problems could be dysfunction of the visual-perceptual system (see Chapter 28) or vestibular system (see Chapter 22), dyspraxia (see Chapter 14), or dysfunction caused by cerebellar damage (see Chapter 21). If possible, the factors involved in producing a lack of coordination should be identified.

Examples of handling techniques that can be adapted to enhance the individual’s progression through the sequence of functional activities can be found in the works of Bobath,38 Carr and Shepherd,39,40 Duncan and Badke,41 Levitt,42 Ryerson and Levit,43 Sullivan and Markos,44 and Voss and colleagues,45 as well as throughout this book. These authors can provide the therapist with ideas for ways to enhance the client’s performance within a specific activity.

The potential for an exaggerated and inappropriate response to sensory input was discussed as part of the clinical picture. Before the therapist expects the client to exhibit adaptive behavior to the potential bombardment of input from combinations of cutaneous, proprioceptive, auditory, and visual input, the therapist must assess the client’s ability to respond to multisensory inputs. The ability to respond adaptively progresses from a response to a single sensory system input, to a response to the input in the presence of multiple system input, and then to an adaptive response based on inputs from two or more sources. The therapist must be sure that adding more sensory inputs augments an adaptive response rather than detracting from it. The client may respond to handling techniques that provide proprioceptive and cutaneous cues but may demonstrate a deterioration of performance when auditory input is added. When verbal cues are added, the therapist should follow the philosophy that verbal commands should be concise, sparse, and appropriately timed.45

All sensory inputs should evoke the correct response on the part of the client, rather than cause her or him to sift through the jumble of inputs to recognize the appropriate inputs to which a response should be made. At the highest level the client will demonstrate cross-modal learning in which input from one sensory system will evoke a response based on input previously obtained through a different system. Recognition of a comb by touch is based on the precept of “combness” usually obtained initially by visual input. If the therapist recognizes the hierarchy in the process of integrating sensory input, intervention situations that require too high a level of performance from the client can be avoided. The client who can respond adaptively to input from only one source would not be expected to perform in a crowded treatment area that presents extraneous visual and auditory input. The therapist will also recognize the need to include in the intervention plan situations that involve the controlled introduction of sensory inputs so that the client progresses toward the ability to deal with multiple inputs. Carr and Shepherd40 discuss some general principles that can be used during the training of motor tasks in the presence of somatosensory and perceptual-cognitive impairments.

Dysfunctions in perceptual integration are addressed as the client moves through functional sequence activities. Although these movement activities would not provide the total program for an individual with a specific perceptual integration dysfunction, goals in this area can be addressed if the therapist is aware of indications of dysfunctions. The therapist must critically observe the performance of a movement sequence to identify substitute actions to compensate for problems such as inability to cross the midline. The therapist must then attempt to redesign the demands of the situation to elicit the desired behavior. The client who moves from the supine to the side sitting to the long sitting positions without the upper extremities crossing the midline could be required to side sit to the left and transfer objects with the right hand from the left side of the body to the right side (Figure 26-9). The therapist must determine whether the client is truly crossing the midline or rotating the midline of the body to continue to avoid crossing it.

Clients who are performing at higher levels can be challenged to maintain balance when one element of the sensory triad is missing (e.g., vision occluded) or altered (e.g., sitting, standing, or walking on a soft, compliant surface). Successful maintenance of balance outside the protective environment of the therapy clinic requires the ability to switch the primary information source to any one of the three systems. Walking in the dark requires the person to rely on vestibular and somatosensory input. Standing on a moving bus looking out a window requires resolution of the conflict between visual input (the external world is moving), vestibular input (you are moving), and somatosensory input (you are stationary). Movement experiences within the therapy program should foster practice of this sensory integration process (see Table 26-2).