38 Infective meningitis

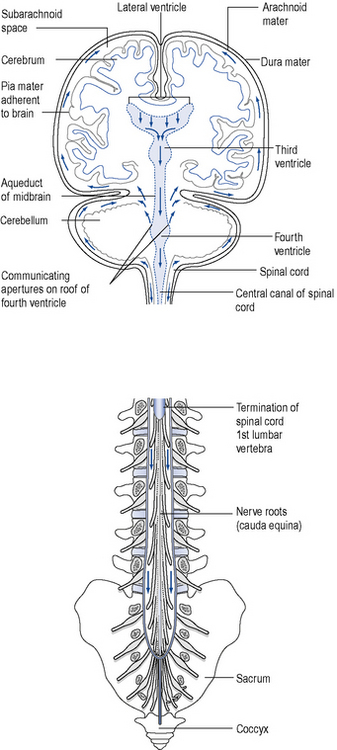

The brain and spinal cord are surrounded by three membranes, which from the outside inwards are the dura mater, the arachnoid mater and the pia mater. Between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater, in the subarachnoid space, is found the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Fig. 38.1). This fluid, of which there is ∼︀150 mL–1 in a normal individual, is secreted by the choroid plexuses and vascular structures which are in the third, fourth and lateral ventricles. CSF passes from the ventricles via communicating apertures to the subarachnoid space, after which it flows over the surface of the brain and the spinal cord (see Fig. 38.1). The amount of CSF is controlled by resorption into the bloodstream by vascular structures in the subarachnoid space, called the arachnoid villi. Infective meningitis is an inflammation of the arachnoid and pia mater associated with the presence of bacteria, viruses, fungi or protozoa in the CSF. Meningitis is one of the most emotive of infectious diseases, and for good reason: even today, infective meningitis is associated with significant mortality and risk of serious sequelae in survivors.

Fig. 38.1 The meninges covering the brain and spinal cord and the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (arrowed)

(modified from Ross and Wilson (1981), by permission of Churchill Livingstone).

Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

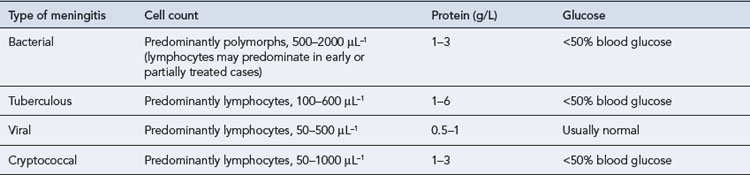

In health, the CSF is a clear colourless fluid which, in the lumbar region of the spinal cord, is at a pressure of 50–150 mmH2O. There may be up to 5 cells/μL, the protein concentration is up to 0.4 g/L and the glucose concentration is at least 60% of the blood glucose (usually 2.2–4.4 mmol/L). Table 38.1 shows how the cell count and biochemical measurements can be helpful in determining the type of organism causing meningitis.

Drug treatment

Antimicrobial therapy

Pharmacokinetic considerations

The antimicrobial therapy of meningitis requires attainment of adequate levels of bactericidal agents within the CSF. The principal route of entry of antibiotics into CSF is by the choroid plexus; an alternative route is via the capillaries of the central nervous system into the extracellular fluid and hence into the ventricles and subarachnoid space (see Fig. 38.1). The passage of antibiotics into CSF is dependent on the degree of meningeal inflammation and integrity of the blood–brain barrier created by capillary endothelial cells, as well as the following properties of the antibiotic:

Antimicrobials fall into three categories according to their ability to penetrate the CSF:

Recommended regimens

Antibiotics for meningitis in neonates and infants aged below 3 months

The most important pathogens in neonates include group B streptococci, E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae, L. monocytogenes. In many centres, a third-generation cephalosporin such as cefotaxime or ceftazidime, along with amoxicillin or ampicillin, is the empiric therapy of choice for neonatal meningitis (Galiza and Heath, 2009). Cephalosporins penetrate into CSF better than aminoglycosides, and their use in Gram-negative bacillary meningitis has contributed to a reduction in mortality to less than 10%. Other centres continue to use an aminoglycoside, such as gentamicin, together with benzylpenicillin, ampicillin or amoxicillin as empiric therapy. This approach remains appropriate, especially in countries such as the UK where group B streptococci are by far the predominant cause of early-onset neonatal meningitis. Whichever empiric regimen is used, therapy can be altered as appropriate once the pathogen has been identified. Suitable dosages are shown in Table 38.2.

Table 38.2 Suitable antibiotic regimens for treatment of acute bacterial meningitis in different age groups

| Age group | First-choice antibiotic therapy | Alternative therapies |

|---|---|---|

| Neonates, aged <8 days | Ampicillin, 50 mg/kg twice daily or amoxicillin 25 mg/kg twice daily and cefotaxime 50 mg/kg twice daily or ceftazidime 50 mg/kg twice daily | Benzylpenicillin 50 mg twice daily and ampicillin 50 mg/kg twice daily or amoxicillin 25 mg/kg twice daily and gentamicin 2.5 mg/kg twice daily |

| Neonates, aged 8–28 days | Ampicillin 50 mg/kg four times daily or amoxicillin 25 mg/kg three times daily and cefotaxime 50 mg/kg three times daily or ceftazidime 50 mg/kg three times daily | Benzylpencillin 50 mg three or four times daily or ampicillin 50 mg/kg three or four times daily or amoxicillin 25 mg/kg three times daily and gentamicin 2.5 mg/kg three times daily |

| Infants, aged 1–3 months | Ampicillin 50 mg/kg four times daily or amoxicillin 25 mg/kg three times daily and cefotaxime 50 mg/kg three times daily or ceftriaxone 75–100 mg/kg once daily | |

| Infants and children aged >3 monthsa | Cefotaxime 50 mg/kg three times daily or ceftriaxoneb 75–100 mg/kg once daily | Ampicillin 50 mg/kg four times daily or amoxicillin 25 mg/kg three times daily or benzylpenicillinc 30 mg/kg 4-hourly and chloramphenicold 12.5–25 mg/kg four times daily |

| Adults | Cefotaximee 2 g three times daily or ceftriaxoneb,e 2–4 g once daily | Benzylpenicillin 2.4 g 4-hourly or ampicillin 2–3 g four times daily or amoxicillin 2 g three or four times daily and chloramphenicold 12.5–25 mg/kg four times daily |

a Calculated doses for children should not exceed maximum recommended doses for adults.

b Ceftriaxone should not be administered to neonates within 48 h of completion of infusions of calcium-containing solutions; caution should be exercised in older age groups.

c Benzylpenicillin is inactive against H. influenzae and should therefore not be used in children aged <5 years.

d Monitoring of serum chloramphenicol levels is recommended, especially in children aged ≤4 years.

e Add ampicillin or amoxicillin to cover L. monocytogenes in elderly patients or where Gram-positive bacilli seen in CSF.

Antibiotics for meningitis in older infants, children and adults

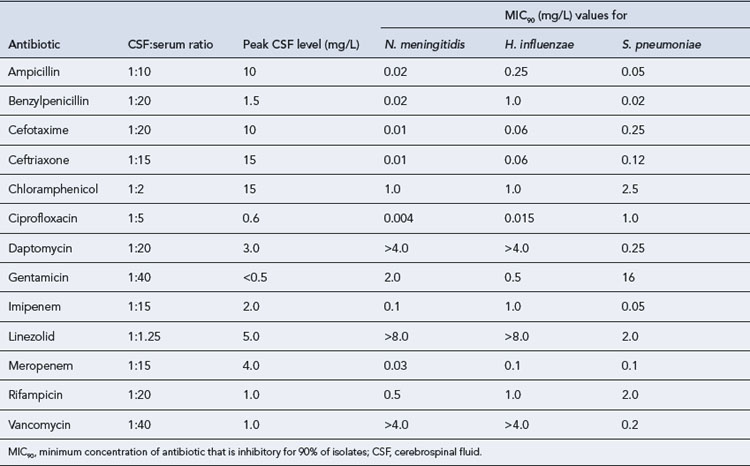

Antimicrobial therapy has to cover S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis and, in children aged below 5 years, H. influenzae (Yogev and Guzman-Cottrill, 2005). Achievable antibiotic CSF concentrations are compared with the susceptibilities of the common agents of meningitis in Table 38.3. Third-generation cephalosporins, such as cefotaxime, are now widely used in place of the traditional agents of choice, chloramphenicol, ampicillin, amoxicillin and penicillin (see Table 38.2). This change has stemmed from concern over the rare but potentially serious adverse effects of chloramphenicol and the emergence of resistance to penicillin, ampicillin and chloramphenicol among S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae in particular. Chloramphenicol resistance and reduced susceptibility to penicillin have also been reported in N. meningitidis. The third-generation cephalosporins have a broad spectrum of activity that encompasses not only the three classic causes of bacterial meningitis but also many other bacteria that are infrequent causes of meningitis. However, cephalosporins are inactive against L. monocytogenes, and amoxicillin or ampicillin should be added where it is possible that the patient may have listeriosis, for example in elderly patients, or where Gram-positive bacilli are seen on Gram stain. Although earlier-generation cephalosporins such as cefuroxime achieve reasonable CSF penetration and are active against the agents of meningitis in vitro, they do not effectively sterilise the CSF and should not be used to treat meningitis.

Table 38.3 Achievable CSF concentrations of antibiotics in meningitis and MIC values for common central nervous system pathogens

S. pneumoniae

Although currently only about 5% of pneumococci in the UK are penicillin resistant, the frequency of resistance is increasing, and resistance rates of more than 50% have been reported in other countries, including Spain, Hungary and South Africa. Penicillin resistance in pneumococci is defined in terms of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of penicillin. Most strains have a MIC value of 0.1–2.0 mg/L and are defined as having moderate resistance; strains with an MIC value of more than 2 mg/L are considered highly resistant. This distinction is relevant for less serious infections with moderately resistant strains, which may still respond to adequate doses of some β-lactam antibiotics, such as cefotaxime, ceftriaxone or a carbapenem. However, the clinical outcome of meningitis with penicillin-resistant pneumococci treated with a β-lactam antibiotic as monotherapy is less good. For this reason, many guidelines, including those produced by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, now recommend therapy with a combination of a third-generation cephalosporin and vancomycin (McIntosh, 2005). This approach has not been adopted universally in the UK but should certainly be considered for patients who might have acquired their infection in a location where the incidence of penicillin resistance is high. Where vancomycin is given intravenously to treat meningitis, it is important to aim for trough serum levels of 15–20 mg/L because of the limited CSF penetration of vancomycin. Another problem is the emergence of pneumococci that are tolerant to vancomycin, that is, they are able to survive, but not proliferate, in the presence of vancomycin. Although such strains are uncommon, the outcome of meningitis treated with vancomycin is poor (Cottagnoud and Tauber, 2004).

Consideration of alternative antibiotics for treatment of penicillin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis is largely based on case reports rather than clinical trials. Success has been reported with meropenem as monotherapy, and in conjunction with rifampicin. Moxifloxacin is a new-generation quinolone antibiotic with enhanced activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including S. pneumoniae, which has shown promise in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Linezolid has excellent CSF penetration but does not have bactericidal activity, and clinical experience in treating meningitis has been variable (Rupprecht and Pfister, 2005).

Chemoprophylaxis against meningococccal and Hib infection

In meningococcal meningitis, spread between family members and other close contacts is well recognised; these individuals should receive chemoprophylaxis as soon as possible, preferably within 24 h. Sometimes, chemoprophylaxis may be indicated for other contacts, but the decision to offer prophylaxis beyond household contacts should only be made after obtaining expert advice (Box 38.1). Of the antibiotics conventionally used to treat meningococcal infections, only ceftriaxone reliably eliminates nasopharyngeal carriage; where another antibiotic has been used for treatment, the index case also requires chemoprophylaxis. A number of antibiotics are suitable as prophylaxis (Box 38.2).

Neisseria meningitidis

Invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b infection

| Meningococcal infection | |

| Ciprofloxacina (oral) | |

| Children aged 1 month – 4 years Children aged 5–12 years Adults |

125 mg as a single dose 250 mg as a single dose 500 mg as a single dose |

| Rifampicin (oral) | |

| Children aged <1 year | 5 mg/kg twice daily on 2 consecutive days |

| Children aged 1–12 years | 10 mg/kg (max 600 mg) twice daily on 2 consecutive days |

| Adults | 600 mg twice daily on 2 consecutive days |

| Azithromycina (oral)Pregnant women | 500 mg as a single dose |

| Ceftriaxonea (intramuscular) | |

| Children aged <12 years Adults |

125 mg as a single dose 250 mg as a single dose |

| Invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b infection | |

| Rifampicin (oral) | |

| Children aged 1–3 months | 10 mg/kg once daily for 4 days |

| Children aged >3 months | 20 mg/kg once daily (max 600 mg) for 4 days |

| Adultsb | 600 mg once daily for 4 days |

Chemoprophylaxis against Hib infection is usually only indicated where there is an unimmunised child in the vulnerable age group in the household (see Box 38.1). Only rifampicin has been proved to be effective in eliminating nasopharyngeal carriage (see Box 38.2). Unimmunised household contacts aged below 4 years should also receive Hib vaccine. The index case should also receive rifampicin in order to eliminate nasopharyngeal carriage, and should be immunised, irrespective of age.

Antibiotics for meningitis in special groups

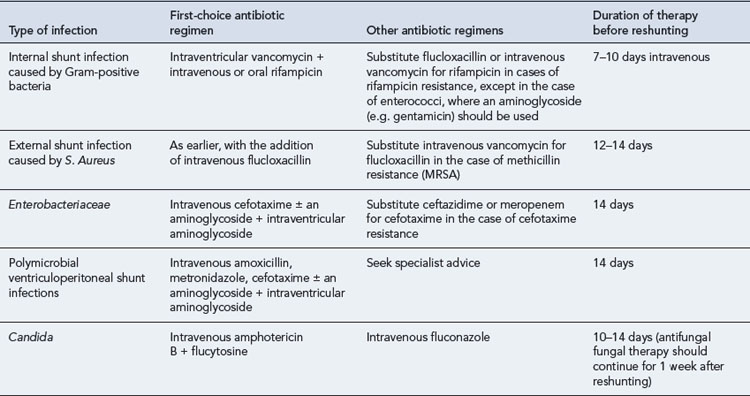

Shunt-associated meningitis

Patients who have a ventricular shunt are at increased risk of meningitis. Shunt-associated infections are classified according to the site of initial infection. Internal infections, where the lumen of the shunt is colonised, constitute the majority of cases. External shunt infections involve the tissues surrounding the shunt. Most internal shunt infections are caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci. S. aureus and Enterobacteriaceae account for most external infections. It is generally held that management of shunt infections should include shunt removal, as well as antibiotic therapy (Infection in Neurosurgery Working Party, 2000), although the need for this has been questioned (Arnell et al., 2007). Appropriate antimicrobial regimens are shown in Table 38.4.

Tuberculous meningitis

The outcome in tuberculous meningitis relates directly to the severity of the patient’s clinical condition on commencement of therapy. A satisfactory response demands a high degree of clinical suspicion such that appropriate chemotherapy is initiated early, even if tubercle bacilli are not demonstrated on initial microscopy. Most currently used antituberculous agents achieve effective concentrations in the CSF in tuberculous meningitis. Detailed discussion of antituberculous therapy is given in Chapter 40. Adjunctive steroid therapy is of value in patients with more severe disease, particularly those who suddenly develop cerebral oedema soon after starting treatment or who appear to be developing a spinal block. However, routine use of steroids is not recommended. They may suppress informative changes in the CSF and interfere with antibiotic penetration by restoring the blood–brain barrier. Early neurosurgical management of hydrocephalus by means of a ventriculoperitoneal or ventriculoatrial shunt is also important in improving the prospects for neurological recovery.

Cryptococcal meningitis

Patients with HIV infection treated for cryptococcal meningitis should then receive fluconazole indefinitely, or at least until immune reconstitution occurs. The dose of fluconazole may be reduced to 200 mg/day, depending on the patient’s clinical condition (Bicanic and Harrison, 2004). Itraconazole offers less good CSF penetration than fluconazole, but is a suitable alternative as maintenance therapy at a dose of 200–400 mg/day for patients unable to tolerate fluconazole. Clinical data with newer triazoles such as voriconazole and posaconazole remain limited, but these agents may be useful, especially in the rare situation of fluconazole-resistant cryptococcal meningitis. The echinocandin class of antifungals does not possess useful activity against Cryptococcus.

Viral meningitis

None of the currently available antiviral agents has useful activity against human enteroviruses, the commonest causes of viral meningitis (Big et al., 2009). Fortunately, however, the condition is usually self-limiting. The viruses that commonly cause this condition, herpes simplex and varicella zoster meningoencephalitis, are treated with high-dose aciclovir, 10 mg/kg three times daily for at least 10 days (adults and children aged 12 years and over). For younger children, the recommended doses are 20 mg/kg three times daily for infants up to age 3 months, and 500 mg/m2 three times daily for those aged 3 months to 12 years.

Steroids as adjunctive therapy in bacterial meningitis

In pharmacological doses, corticosteroids, and in particular dexamethasone, regulate many components of the inflammatory response and also lower CSF hydrostatic pressure. However, by reducing inflammation and restoring the blood–brain barrier, they may reduce CSF penetration of antibiotics. The benefits of steroids in the initial management of meningitis due to M. tuberculosis and Hib are well established, although in other forms of bacterial meningitis the evidence has been less compelling. Methodological flaws have been identified in older studies where no benefit was seen from use of adjunctive steroid therapy. Recent work has found that adjunctive dexamethasone therapy reduces the rate of unfavourable outcomes from 25% to 15% in adults with bacterial meningitis. In this series, adjunctive treatment with dexamethasone was given before or with the first dose of antibiotics, without serious adverse effects. Overall, corticosteroids significantly reduce rates of mortality, severe hearing loss and neurological sequelae. The use of adjunctive dexamethasone is now recommended for children and adults with community-acquired bacterial meningitis, regardless of bacterial aetiology (Brouwer et al., 2010). Adjunctive therapy should be initiated before or with the first dose of antibiotics and continued for 4 days. The recommended dose for adults is 10 mg four times daily for 4 days (children 0.15 mg/kg four times daily for 4 days).

Intrathecal and intraventricular administration of antibiotics

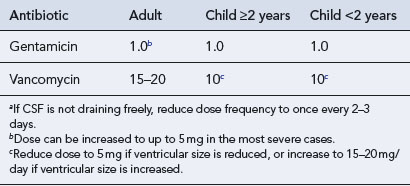

Intrathecal administration, that is, administration into the lumbar subarachnoid space, of antibiotics was once widely used to supplement levels attained by concomitant systemic therapy. However, there is little evidence for the efficacy of this route of delivery, and it is now rarely used. In particular, it produces only low concentrations of antibiotic in the ventricles and therefore does little to prevent ventriculitis, one of the most serious complications of meningitis. Direct intraventricular administration of antibiotics in meningitis is important in certain types of meningitis, especially where it is necessary to use an agent, for example vancomycin or an aminoglycoside, that penetrates CSF poorly (Shah et al., 2004). The most common situation is in shunt-associated meningitis, where multiple antibiotic-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci are the major pathogens, and where conveniently the patient will often have an external ventricular drain through which antibiotics can be administered.

There are considerable differences in recommended doses of antibiotics for intrathecal or intraventricular administration. A dose of 15–20 mg vancomycin per day is recommended for treatment of shunt-associated meningitis in adults with an extraventricular drain, and 10 mg/day for neonates and children. The paediatric dose may need to be reduced to 5 mg/day if ventricular size is reduced, or increased to 15–20 mg/day if the ventricular size is increased. In all patients, the dose frequency should be decreased to once every 2–3 days if CSF is not draining freely. The CSF vancomycin concentration should be measured after 3–4 days, aiming for a trough concentration of <10 mg/L. Recommended doses of antibiotics are otherwise largely based on anecdotal experience (Table 38.5).

Patient care

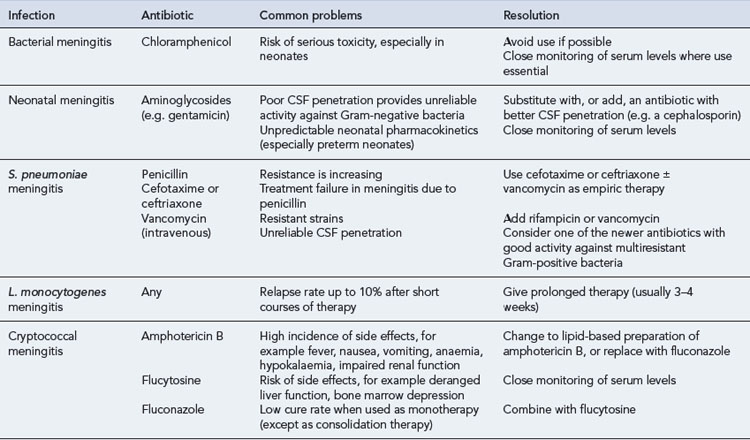

Common problems in the treatment of meningitis are set out in Table 38.6.

Prevention of person-to-person transmission

Questions

Answers

Answers

Answers

Answers

Arnell K., Enblad P., Wester T., et al. Treatment of cerebrospinal fluid shunt infections in children using systemic and intraventricular antibiotic therapy in combination with externalization of the ventricular catheter: efficacy in 34 consecutively treated infections. J. Neurosurg.. 2007;107:213-219.

Bicanic T., Harrison T.S. Cryptococcal meningitis. Br. Med. Bull.. 2004;72:99-118.

Big C., Reineck L.A., Aronoff D.M. Viral infections of the central nervous system: a case-based review. Clin. Med. Res.. 2009;7:142-146.

Brouwer M.C., McIntyre P., de Gans J., et al. Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.. 2010. Issue 9. Art No. CD004405

Cottagnoud P.H., Tauber M.G. New therapies for pneumococcal meningitis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2004;13:393-401.

Galiza E.P., Heath P.T. Improving the outcome of neonatal meningitis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis.. 2009;22:229-234.

Health Protection Agency Meningococcus and Haemophilus Forum. Guidance for Public Health Management of Meningococcal Disease in the UK, updated January. Health Protection Agency. 2011.

Infection in Neurosurgery Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. The management of neurosurgical patients with postoperative bacterial or aseptic meningitis or external ventricular drain-associated ventriculitis. Br. J. Neurosurg.. 2000;14:7-12.

McIntosh E.D. Treatment and prevention strategies to combat pediatric pneumococcal meningitis. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther.. 2005;3:739-750.

Ross J.S., Wilson K.J.W. Foundations of Anatomy and Physiology, fifth ed., Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1981:172-173.

Rupprecht T.A., Pfister H.W. Clinical experience with linezolid for the treatment of central nervous system infections. Eur. J. Neurol.. 2005;12:536-542.

Shah S.S., Ohlsson A., Shah V.S. Intraventricular antibiotics for bacterial meningitis in neonates. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004. Issue 4. Art. No. CD004496. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004496.pub2. Available at http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab004496.html Accessed 20 April 2011

Yogev R., Guzman-Cottrill J. Bacterial meningitis in children: critical review of current concepts. Drugs. 2005;65:1097-1112.

Chang L., Phipps W., Kennedy G., et al. Antifungal interventions for the primary prevention of cryptococcal disease in adults with HIV. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.. 2005. Issue 3. Art. No. CD004773.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004773.pub2

Chaudhuri Chaudhuri A., Martinez-Martin P., Kennedy P.G., et al. EFNS guideline on the management of community-acquired bacterial meningitis: report of an EFNS Task Force on acute bacterial meningitis in older children and adults. Eur. J. Neurol.. 2008;15:649-659.

Chavez-Bueno S., McCracken G.H. Bacterial meningitis in children. Pediatr. Clin. North Am.. 2005;52:795-810.

Correia J.B., Hart C.A. Meningococcal disease. Clin. Evid.. 2004;12:1164-1181.

Riordan A. The implications of vaccines for prevention of bacterial meningitis. Curr. Opin. Neurol.. 2010;23:319-324.

Tunkel A.R., Hartman B.J., Kaplan S.L., et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2004;39:1267-1284.

Zunt J.R. Infections of the central nervous system in the neurosurgical patient. Handb. Clin. Neurol.. 2010;96:125-141.