Infectious Diarrheal Disease and Dehydration

Acute Infectious Diarrhea

The prevalence of acute gastroenteritis in children has not changed much during the past four decades, but the mortality has declined sharply.1 Although dehydration is the most common complication of acute infectious diarrhea, one of the most important reasons for the decline in mortality has been the increasing international support for the use of oral rehydration solutions (ORSs) as the treatment of choice for acute diarrhea. However, in emergency departments (EDs) across the nation, intravenous therapy is still routinely used for treatment of volume depletion due to infectious diarrhea. A few reasons that EDs still routinely use intravenous therapy instead of oral rehydration are the misconceptions that intravenous therapy is more effective, that it takes less time, and that it poses little risk. However, some potential serious complications have emerged as a result of overuse of parenteral rehydration. These include local complications from intravenous infiltrations (hematoma, thrombosis, phlebitis, postinfusion phlebitis, thrombophlebitis, infiltration, local infection, extravasation, and vasospasm) and systemic complications from overly aggressive replacement of volume deficits leading to central nervous system sequelae and pulmonary edema. In many situations, diarrhea-related volume depletion can be treated by enteral replacement by oral intake or delivered by nasogastric or orogastric tubes.

Epidemiology

In 2008, of the estimated 8.795 million deaths in children younger than 5 years worldwide, infectious diseases caused 5.970 million (68%) of these deaths. The largest percentages were due to pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria (in decreasing order). Diarrhea was responsible for 15% or 1.336 million of these deaths.2 Regional differences in resources, epidemiology, underlying general health status of the population, and availability of safe food and water affect the actual disease burden. In the United States, acute gastroenteritis historically accounts for approximately 10% of hospital admissions of children younger than 5 years, estimated at 220,000 admissions per year; 300 to 400 deaths per year are caused by diarrhea, most occurring in the first year of life.2,3 In the United States, acute gastroenteritis is responsible for 3.7 million physician visits, 135,000 to 220,000 pediatric admissions (approximately 10% of total hospitalization for children younger than 5 years), and 150 to 300 deaths among children younger than 5 years.3–5 Costs to society are significant, with approximately one billion dollars in total costs attributed to rotavirus alone.6,7 The incidence of diarrhea in children younger than 3 years has been estimated to be 1.3 to 2.3 episodes per child per year; rates in children attending daycare centers are higher.

Pediatric death due to diarrhea is related to severe dehydration and associated complications. Improvements in recognition and treatment of dehydration have prevented many deaths in the United States. Risks factors for death from diarrhea include age younger than 1 year; birth weight less than 2500 g; African American, Hispanic American, or American Indian ethnicity; immunocompromise; and illness during winter months.3,4

In the United States, viruses are responsible for most cases of acute infectious diarrhea. Rotavirus, norovirus, astrovirus, and enteric adenovirus have been recognized as the most common agents responsible for viral diarrhea in children. Bacteria cause approximately 7 to 10% of cases of acute infectious diarrhea. The most common bacteria are Escherichia coli, Campylobacter species, Salmonella species, Shigella species, and Yersinia enterocolitica. Clostridium difficile is also seen as a cause of infectious diarrhea, especially in patients who have recently taken antibiotics and hospitalized patients. Parasitic causes of infectious diarrhea are uncommon in the immunocompetent patient, but they can occur. The most common parasitic organisms are Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Entamoeba histolytica.8–11 Infectious diarrhea in children is most often contracted through the fecal-oral route and through poor food-handling practices. Daycare centers remain a main source of cases, with infection spread by diaper handling, fecal-oral transmission, and sharing of toys. Causative agents may be endemic, epidemic with food- and water-borne outbreaks, or sporadic. For most agents, a large inoculum is required to transmit the illness. The exceptions are Campylobacter, Giardia, and Shigella, for which 10 to 200 organisms are sufficient to cause disease. Some groups are at higher risk for acquiring infectious diarrhea and suffer greater clinical consequences. Among these are premature infants, young infants (<3 months), and patients who are immunosuppressed or malnourished or who have a chronic disease. Recent hospitalization, treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, and travel to developing countries are additional risk factors.

Principles of Disease

Definitions.: Secretory diarrhea is the result of increased intestinal secretion caused by a variety of mechanisms. In the case of Vibrio cholerae, an enterotoxin causes an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in the endothelial cell, resulting in increased chloride and bicarbonate secretion. Clinically, secretory diarrhea is often characterized by the absence of expected reduction in stool volume with fasting, a stool pH above 6, and the absence of reducing substances in the stool. Other bacteria that produce enterotoxins include Salmonella, Shigella, E. coli, and C. difficile.

Before the diagnosis of acute infectious diarrhea is established, other potentially life-threatening illnesses that can be manifested with diarrhea with or without vomiting should be excluded. This can usually be accomplished with a thorough history and physical examination (Tables 173-1 and 173-2).

Table 173-1

Common Causes of Vomiting in Children

| ETIOLOGIC CATEGORY | CLINICAL SYNDROMES |

| Central nervous system | Infections, space-occupying lesion |

| Gastrointestinal | Obstruction, peritonitis, hepatitis, liver failure, appendicitis, pyloric stenosis, midgut volvulus, intussusception, inborn errors of metabolism |

| Drug | Ingestion, overdose, drug effect |

| Endocrine | Addisonian crisis, diabetic ketoacidosis, congenital adrenal hyperplasia |

| Renal | Urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis, renal failure, renal tubular acidosis |

| Cardiac | Congestive heart failure of any cause |

| Infection | Pneumonia, acute otitis media, sinusitis, sepsis |

| Other | Psychogenic, respiratory insufficiency |

Table 173-2

Common Causes of Diarrhea in Children

| ETIOLOGIC CATEGORY | CLINICAL SYNDROMES |

| Gastrointestinal | Malabsorption (e.g., milk intolerance, excessive fruit juice), intussusception, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, short gut syndrome |

| Drug | Ingestion, overdose, drug effect |

| Endocrine | Thyrotoxicosis, addisonian crisis, diabetic enteropathy, congenital adrenal hyperplasia |

| Renal | Urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis |

| Infection | Pneumonia, acute otitis media, sinusitis, sepsis |

| Other | Parental anxiety, chronic nonspecific diarrhea |

Etiology

A variety of viruses, bacteria, and protozoa can cause acute infectious diarrhea in children (Table 173-3). In developed countries such as the United States, viral causes predominate. In countries in which access to clean water and food supply is limited, bacterial agents contribute the major portion of the morbidity and mortality associated with infectious diarrhea.

Table 173-3

Viruses

Rotavirus is the leading cause of diarrhea worldwide among children younger than 5 years.12 In the United States, rotavirus is responsible for 410,000 office visits, 205,000 to 272,000 ED visits, and 55,000 to 77,000 hospitalizations each year. This virus is endemic and accounts for nearly one third of the cases in children with diarrhea. The number of cases of rotavirus infection peaks in the winter and spring. Rotavirus causes acute illness with vomiting and diarrhea that may or may not be associated with fever. The diarrhea is watery, and the volume may be large enough to result in significant and rapid intravascular volume depletion. Rotavirus also may cause symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection. Most infections are transmitted person to person through the fecal-oral route. There is also evidence that it may be transmitted through respiratory secretions as airborne droplets. The incubation period is 1 to 3 days. Postinfection excretion may be prolonged up to 21 days after the onset of symptoms in the immunocompetent patient.13

Rotavirus selectively destroys the villus tip cells in the small intestine, leading to malabsorption and diarrhea. A proliferative response occurs, producing an abundance of incompletely differentiated cells in the gut mucosa. In the healthy host, repair of the epithelium and differentiation of the immature brush border take approximately 3 to 5 days and occur without specific intervention. In the chronically ill or malnourished child, the infection may lead to complications beyond the usual brush border injury. Failure to repair the epithelium leads to the vicious circle of malnutrition and progressive epithelial injury.13

Diagnosis is made by demonstration of antigens in stool specimens by enzyme immunoassay. Modern assays have up to 97% sensitivity and 97% specificity for rotavirus antigens in human stool. The test can be performed on undiluted stool without special preparation. Results are usually available within 24 hours.13

An effective vaccine was available for a short time (1998-1999) until it was noted to be associated with increased risk of intussusception, usually occurring 3 to 20 days after administration. This vaccine was subsequently withdrawn from the U.S. market.14 Until recently, only two orally administered live virus vaccines were licensed for use among infants in the United States. RotaTeq vaccine was licensed in 2006 as a three-dose series, and in 2008 Rotarix, a live oral human attenuated vaccine, was licensed as a two-dose series for infants. The American Academy of Pediatrics does not express a preference for either vaccine. To date, no association with intussusception has been reported.15,16 Preliminary surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have noted a 64% decrease among rotavirus-positive test results in the first year after vaccine release.17 Recently, a new vaccine was introduced, the RV1 vaccine; studies in Brazil and Mexico show the risk of intussusception after RV1 vaccine to be 1 in 51,000 to 68,000. The authors concluded that this increased risk results in an annual excess of 96 hospitalizations and that this risk is outweighed by the benefit of the vaccine, which prevented 80,000 admissions and 1300 deaths.17

Noroviruses (previously known as Norwalk-like viruses) are the second most common cause of childhood acute infectious diarrhea. Norovirus accounts for approximately 12% of severe gastroenteritis among children younger than 5 years. In the United States, norovirus is responsible for more than 235,000 clinic visits, 91,000 ED visits, and 23,000 hospitalizations for children younger than 5 years.18,19 Infection can occur year-round and in any age group but is most common during the colder months of the year. This virus causes the abrupt onset of watery diarrhea with or without vomiting. It is often accompanied by abdominal cramps and nausea. It is a self-limited disease, lasting 2 or 3 days. This virus can be transmitted person to person by the fecal-oral route as well as through contaminated food and water sources. In the United States, norovirus accounts for more than 90% of community outbreaks associated with viral gastroenteritis, which occur in all age groups. Common-source outbreaks in long-term care facilities contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality among the residents. In addition, these agents most commonly are associated with outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis on cruise ships and in schools and hospitals. The incubation period is 12 to 48 hours, and the excretion of the virus lasts 5 to 7 days after the onset of symptoms in approximately 50% of infected people. In about 25% the excretion of the virus can be up to 3 weeks, and asymptomatic excretion can be longer in the immunocompromised.20

Astrovirus infections occur mostly in children younger than 4 years; cases peak in the late winter and early spring in the United States. The illness is characterized by diarrhea of short duration (a few days) accompanied by vomiting, fever, and occasionally abdominal pain. The incubation period is 1 to 4 days and transmission is person to person by the fecal-oral route. Viral shedding may begin a day before symptoms start and can continue for several days after cessation of diarrhea. However, asymptomatic shedding has been seen to last up to several weeks after the symptoms of the illness have resolved in healthy children There are no commercial tests for diagnosis in the United States, but enzyme immunoassays are available in many other countries. There are a few different tests available in some research and reference laboratories; the reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction assay is the most sensitive.21

Adenovirus is well known for causing infections of the respiratory tract along with pharyngitis, otitis media, and pharyngoconjunctival fever. Enteric adenovirus serotypes cause gastroenteritis. These strains are transmitted through the fecal-oral route. Enteric disease occurs throughout the year and affects children younger than 4 years more commonly. The incubation period is 3 to 10 days. It is most contagious during the first few days of the acute illness, but asymptomatic shedding of the virus for months is not uncommon.22

Bacteria

Salmonella infections usually are divided into those caused by nontyphoidal Salmonella and Salmonella typhi (typhoid fever). Nontyphoidal Salmonella account for more than 98% of the cases in the United States. Infection can result in an asymptomatic carrier state, acute gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and a disseminated abscess syndrome. It is thought that salmonellae invade the mucosa of the distal small intestine as well as the colon and produce a cholera-like enterotoxin and a cytotoxin. It is an illness marked by diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, and fever; it may be manifested as dysentery or a cholera-like illness. Acute gastroenteritis occurs at any age but is most common in the first 4 years of life. Sustained or intermittent bacteremia can occur, and focal infections are seen in up to 10% of patients with Salmonella bacteremia. Animal reservoirs include poultry, livestock, and reptiles, which may be kept as pets by young children. Transmission is usually through foods such as poultry, beef, eggs, and dairy products. Other modes of transmission include ingestion of contaminated water and contact with infected reptiles, amphibians, and possibly rodents. The incubation period for gastroenteritis is 12 to 36 hours (range, 6-72 hours). Invasive disease and mortality are higher for infants and those with immunosuppressive conditions, hemoglobinopathies (e.g., sickle cell disease), malignant neoplasms, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.23

Although it is uncommon, Salmonella serotype typhi can cause a bacteremic illness often referred to as enteric or typhoid fever. S. typhi is found only in humans, and infection implies direct contact with an infected person or with an item contaminated by a carrier. It is uncommon in the United States (approximately 400 cases per year) but is endemic in many countries. Consequently, typhoid fever infections in people in the United States usually are acquired during international travel. There is a gradual onset of symptoms that include fever, headache, malaise, anorexia, lethargy, abdominal pain, and tenderness. Patients may have hepatosplenomegaly, rose spots, and a change in mental status. It may appear as a nonspecific febrile illness in young children, in whom sustained or intermittent bacteremia may occur. Constipation is often seen early in the course of the disease, but diarrhea does occur in children.23

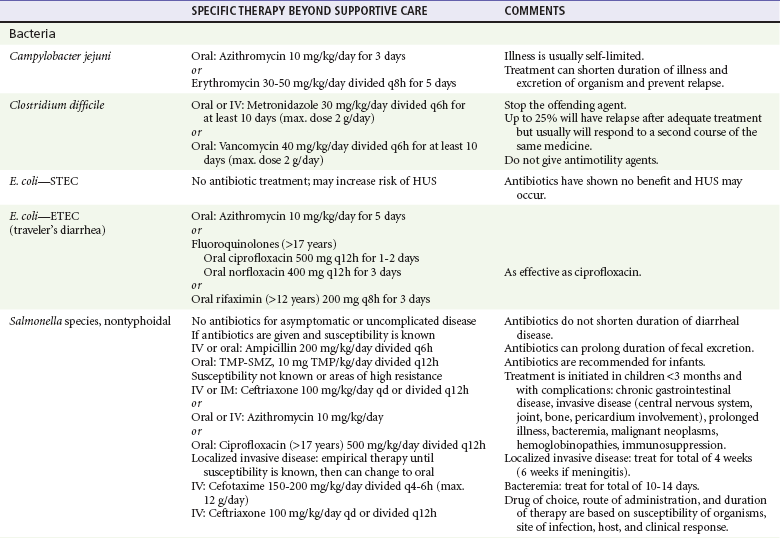

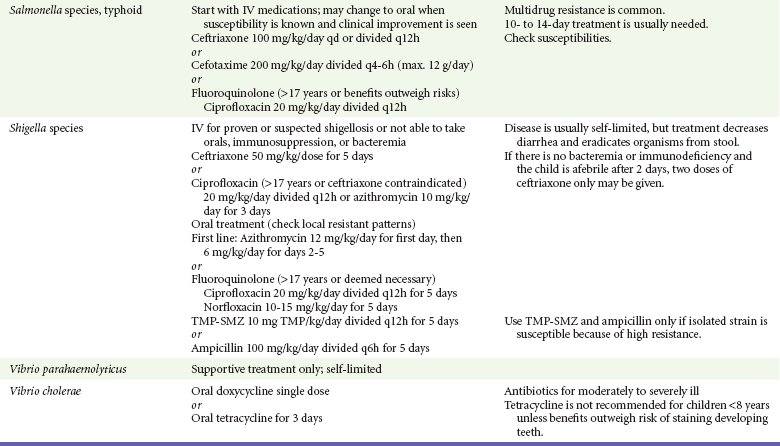

Treatment of nontyphoidal Salmonella infection is usually supportive. Antibiotics given to patients with nontyphoidal Salmonella infections have been found not only to be ineffective in shortening the duration of symptoms but also to prolong the carrier state. Therefore, antibiotics are generally not recommended for asymptomatic cases or for uncomplicated cases. Antibiotic treatment is indicated in infants younger than 3 months or those with complications (such as failure to improve within 5 to 7 days; bacteremia; focal infection in the central nervous system, bone, joint, kidney, or pericardium; and immunosuppressive conditions, hemoglobinopathies, malignant neoplasms, HIV infection, or chronic gastrointestinal disease). If treatment is necessary, ampicillin, amoxicillin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole usually is effective. Because of changing resistance patterns, susceptibility testing should be performed on all isolates. In areas where resistance to these antibiotics is common, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, azithromycin, and fluoroquinolones are usually effective (fluoroquinolones are not recommended in people younger than 18 years) (Table 173-4).

Table 173-4

Diarrheal Pathogens in Children and Specific Therapy

Data from Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS (eds): Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009; and Custer JW, Rau RE (eds): The Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers, 18th ed. Philadelphia, Mosby–Year Book, 2009.

For children with S. typhi infection, antibiotics are recommended. Multidrug-resistant isolates of S. typhi are common, often requiring empirical treatment with an antibiotic such as an expanded-spectrum cephalosporin, azithromycin, or fluoroquinolone. Relapse of enteric fever occurs in up to 15% of patients and requires re-treatment. Treatment failures have occurred in people treated with cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and furazolidone despite in vitro testing indicating susceptibility.23

Shigella species consist of four antigenic groups of 40 serotypes. Among Shigella isolates reported in industrialized nations, including the United States, approximately 86% are Shigella sonnei, 12% are Shigella flexneri, 3% are Shigella boydii, and less than 1% are Shigella dysenteriae.24

S. sonnei is the most common cause of dysentery (diarrhea with significant blood, pus, and mucus) in the United States. Shigellosis usually begins as an enterotoxin-like secretory diarrhea with watery stools and fever that may progress to bacillary dysentery with or without systemic manifestations. Clinical illness varies from mild to severe, with some patients exhibiting abdominal cramps and tenderness. Shigellosis rarely infects infants younger than 3 months and is most common between 2 and 3 years of age. Symptoms usually are self-limited and resolve within 72 hours. Extraintestinal symptoms and signs are relatively common in children with Shigella infection and may include hallucinations, confusion, and seizures. Reactive arthritis can occur weeks after the infection. Rare complications of Shigella infection include bacteremia, hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), and encephalopathy (Ekiri syndrome). Ingestion of as little as 10 to 200 organisms is all that is needed for infection to occur. Transmission occurs through the fecal-oral route, contact with contaminated objects, ingestion of contaminated food or water, and sexual contact. Children 5 years and younger in daycare settings, their caregivers, and other people living in crowded conditions are at increased risk for infection. Travel to developing countries with inadequate sanitation also increases the traveler’s risk for infection. Houseflies may also be vectors through transport of infected feces. The incubation period varies from 1 to 7 days. With or without antibiotics, the carrier state usually lasts about 1 week from the onset of symptoms; chronic carrier state is rare. Antibiotics are reserved for patients with prolonged symptoms, dysentery, or underlying immune compromise.25 For this high-risk population of patients, if Shigella is suspected (patient with contact with a person with Shigella or a known regional outbreak), it is recommended that empirical treatment be started while culture and susceptibility results are awaited. According to the CDC surveillance data from 2000 to 2009, approximately 40 to 60% of isolates were resistant to ampicillin, approximately 30% were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and less than 1% were resistant to ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin.24 Therefore, parenteral ceftriaxone or an oral fluoroquinolone (such as ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin) could be used for 5 days in adult patients who are seriously ill. For less ill adult patients, an oral fluoroquinolone is recommended. In children, parenteral ceftriaxone for seriously ill children or oral azithromycin for less ill children is recommended. Therapy is usually recommended for 5 days. A 2-day course of ceftriaxone may be used if there is a good clinical response and no extraintestinal infection25 (see Table 173-4).

Campylobacter species cause a significant proportion of diarrheal disease worldwide, with 2.4 million cases yearly in the United States. According to data from the CDC, there has been a 30% decline in the incidence of infection since 1996.26 Children younger than 5 years have the highest rate of infection. It takes as few as 500 Campylobacter organisms to cause infection in exposed people. The organism is found in the gastrointestinal tracts and feces of fowl, farm animals, and pets. Of the five types, C. jejuni and C. coli are the most common. Illness consists of abdominal cramps, diarrhea, chills, fever, and Shigella-like dysentery. The clinical presentation may be similar to acute appendicitis or intussusception. Invasion of the mucosa with toxin production has been described. A 1- to 7-day incubation period is normal, and the illness usually lasts less than a week. However, approximately 20% will have a relapse or a prolonged or severe illness. Severe or prolonged disease can mimic inflammatory bowel disease. Campylobacter organisms are transmitted by ingestion of contaminated food (improperly cooked poultry and unpasteurized milk) or untreated water. Fecal-oral spread can occur, especially among very young children with diarrhea. There have been outbreaks in childcare centers, but this is rare. There has also been spread by neonates born to infected mothers that has resulted in outbreaks in nurseries. Excretion typically lasts 2 to 3 weeks without treatment. Diagnosis is made by darkfield microscopy. Oral azithromycin or erythromycin shortens the course of the illness and excretion of organisms and prevents relapse when given early (see Table 173-4). Treatment will usually eradicate the organism from the stool within 2 to 3 days. However, most children will recover without treatment.27

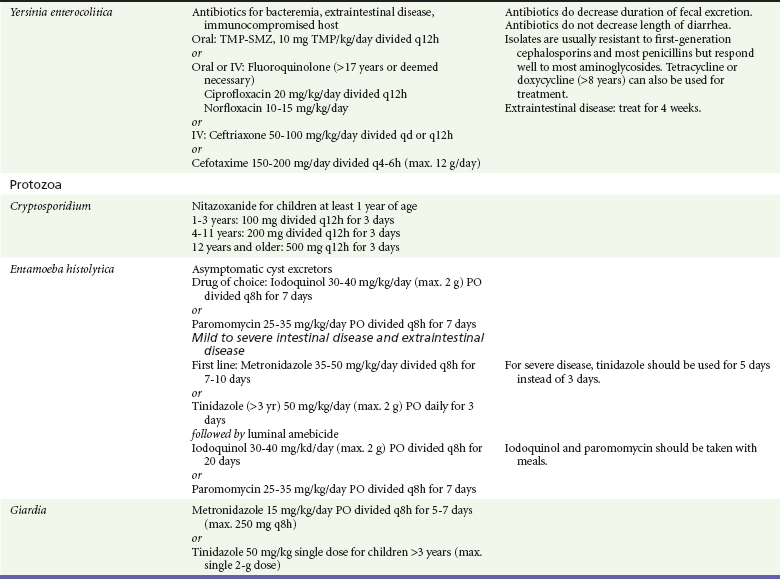

Y. enterocolitica is a relatively uncommon cause of simple self-limited diarrhea and vomiting in the United States. According to the CDC, the mean annual incidence is 0.3 per 100,000 people. However, for children younger than 5 years, the incidence is 1.9 per 100,000.26 Infection usually is manifested with fevers and diarrhea, which may be watery, contain mucus or blood, or both. As many as 6% of older children and adults may present with an appendicitis-like illness with right lower quadrant tenderness, usually as a result of reactive mesenteric adenitis.28 Infections usually result from eating undercooked pork or drinking unpasteurized milk. Symptoms may be prolonged, lasting 14 days or more. There have been no clinical benefits of antimicrobial therapy in the immunocompetent host with enterocolitis or mesenteric adenitis. Antibiotics are indicated for the immunocompromised with enterocolitis and in cases of septicemia and extraintestinal infections. First-line treatment of Y. enterocolitica infection is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and aminoglycosides. Other effective antibiotics include cefotaxime, fluoroquinolones (patients 18 years or older), tetracycline, and doxycycline (patients 8 years of age or older). Isolates are often resistant to first-generation cephalosporins and most penicillins (see Table 173-4).29

C. difficile causes a spectrum of illnesses ranging from asymptomatic to watery diarrhea to pseudomembranous colitis. Patients usually present with diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and fever. Other common features include abdominal tenderness to palpation and dysenteric stools. Complications can include toxic megacolon and intestinal perforation. Severe disease is more common in neutropenic patients with leukemia, in infants with Hirschsprung’s disease, and in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. C. difficile gastroenteritis most often occurs in hospitalized patients, with onset during hospitalization or within 60 days after antibiotic therapy. The organism is transmitted by fecal-oral contamination. Asymptomatic infants can be colonized with the organism; intestinal colonization in healthy neonates and young infants can be as high as 50% but usually is less than 5% in children older than 2 years. The disease is thought to be brought on by the change in the gut flora as a result of antibiotic administration. Incubation time is unknown. Pseudomembranes and friable rectal mucosa are characteristic. C. difficile toxin in the stool is diagnostic. In many institutions the fecal enzyme immunoassay is used for detection of toxins A and B. The results of this test are often available within hours. The sensitivity of this test is approximately 75%. Toxigenic stool culture is the most sensitive test but takes 2 to 3 days for results. Stopping the offending agent and adding therapy with oral or intravenous metronidazole or oral vancomycin for 10 days are indicated (see Table 173-4). Up to 25% of patients experience a relapse after discontinuation of therapy, but the infection usually responds to a second course with the same agent. Drugs that decrease intestinal motility should not be given.30

Ingested C. perfringens organisms produce an enterotoxin during sporulation in the gut that causes fluid collection in ileal loops and diarrhea. The result is a short-lived (usually 24 hours) illness characterized by watery diarrhea, moderate to severe abdominal cramps, and midepigastric pain. Vomiting and fever are uncommon. Food source contamination, often from catered food services (raw meat and poultry, gravies, and dried or precooked foods), is the usual source of outbreaks. The illness cannot be transferred from person to person by the fecal-oral route. The incubation time is 6 to 24 hours. The finding of high spore counts in the stool can make the diagnosis. No specific treatment is required.31

S. aureus produces the “typical” food poisoning from ingestion of preformed enterotoxin, usually from contaminated food. Onset of symptoms is within minutes to hours of exposure. The illness is short-lived (1-2 days) and self-limited. Abrupt and sometimes violent onset of severe nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea without fever is typical. However, low-grade fever or mild hypothermia may occur. Recovery of large numbers of bacteria or enterotoxin from stool or vomitus supports the diagnosis. Treatment is supportive. No antibiotics are indicated as the disease is self-limited.32

V. cholerae is an Asian-African organism that also is seen in South America. Most cases occur in travelers returning from endemic areas. A unique strain is endemic to the Gulf Coast of the United States. The disease is acquired through ingestion of contaminated water and food, such as undercooked shellfish and raw vegetables. Because a large inoculum is required, person-to-person transmission does not occur. Diarrhea is caused by a heat-labile enterotoxin that increases cAMP through adenylate cyclase, resulting in inhibition of sodium reabsorption with chloride and fluid secretion into the gut. The illness is characterized by the painless production of large amounts of watery diarrhea without abdominal cramps or fever. Dehydration, hypokalemia, metabolic acidosis, and occasionally hypovolemic shock can occur within 4 to 12 hours if fluid losses are not replaced. Antibiotic treatment should be considered for patients with moderate to severe disease—oral doxycycline as a single dose or tetracycline for 3 days in severe cholera infection. Although it is not recommended in children younger than 8 years, the benefits may outweigh the risk of staining developing teeth. It has been shown that one course of doxycycline is unlikely to cause significant tooth discoloration. Susceptibility testing is recommended because of changing resistance patterns.33

V. parahaemolyticus is commonly found in seawater, shellfish, and fish. Illness is most commonly associated with ingestion of contaminated raw or undercooked seafood. Diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and nausea are common, whereas vomiting, headache, fever, and chills are less common. The disease usually is self-limited and does not require treatment with antimicrobials.33

E. coli is part of the normal flora in the lower gastrointestinal tract. Several types within this species are recognized to cause disease. Transmission of most diarrhea caused by E. coli is from food or water contaminated with human or animal feces or from infected symptomatic people or carriers. E. coli is identified by distinct groups of either somatic or flagellar antigens that determine virulence properties. The enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) strain produces heat-stable and heat-labile enterotoxins that affect the small intestine and cause a secretory diarrhea. It is common in infants in developing countries and in travelers of all ages. It is uncommon as a cause of diarrhea in the United States. The enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) strain is closely related antigenically and biochemically to Shigella species and can cause a similar dysenteric illness. It invades the large bowel epithelial cells, producing enterotoxins and colonic epithelial cell death. It can cause bloody or nonbloody diarrhea and fever in all ages. The enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) strain is responsible for sporadic and endemic diarrhea. The diarrhea is usually watery and can be severe. The illness occurs predominantly in children younger than 2 years and mainly in developing countries. It can become chronic and cause growth retardation. This form does not produce toxins. The enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) strain causes watery diarrhea in people of all ages in developing and developed countries. It has been associated with a prolonged course. The enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) strain, also known as Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC), produces bloody diarrhea without fever; E. coli O157:H7 is the prototype and most virulent of the EHEC. Outbreaks have been linked to ground beef, exposure to animals in public settings (petting zoos), contaminated apple cider, raw fruits and vegetables, and ingestion of water in recreational areas. The infectious dose is low, and person-to-person transmission is common during outbreaks.34 HUS is a serious sequel of EHEC infection.35

HUS consists of the triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal insufficiency. It typically develops in the second week of illness, often after the diarrhea has resolved. Patients often present with pallor, weakness, irritability, and oliguria or anuria. HUS occurs in up to 20% of children with E. coli O157:H7.36 Approximately 50% of patients who have HUS will require dialysis, and 3 to 5% die. Patients with hemorrhagic colitis should be aggressively hydrated, admitted, and monitored closely (including complete blood cell count with smear and blood urea nitrogen [BUN] and creatinine concentrations) to detect changes suggestive of HUS. If patients have no laboratory evidence of hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, or nephropathy 3 days after resolution of diarrhea, their risk for development of HUS is low.35

Controversy exists about the indications for antibiotic treatment of E. coli diarrhea. Early data indicated that antimicrobials offer no substantial benefit and may increase the risk for development of HUS.37 In addition, in vitro studies have shown that subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations can increase toxin production.38 However, a subsequent meta-analysis failed to confirm the association between the use of antibiotics and the increased risk for HUS.39 In the absence of conclusive evidence, empirical antibiotics should not be administered because of the potential risk of HUS. For severe watery diarrhea in a traveler to a developing country, azithromycin or a fluoroquinolone may be considered in an older child (>18 years).34

Protozoa

Cryptosporidium hominis is the most common of the Cryptosporidium species to infect humans. Children present with frequent, nonbloody, watery diarrhea. Other symptoms may include abdominal cramps, fatigue, fever, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss. Cryptosporidium has been found in mammals, birds, and reptiles.40 Outbreaks have been associated with contaminated municipal water and exposure to contaminated swimming pools. In children, the incidence is greatest during the summer and early fall. Person-to-person spread can occur and can cause outbreaks in daycare centers. In the immunocompetent child, the illness is self-limited, lasting 1 to 20 days. In the immunocompromised patient, chronic, severe diarrhea can develop and result in malnutrition, dehydration, and death. Treatment is usually supportive. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a 3-day course of nitazoxanide oral suspension for the treatment of immunocompetent children older than 1 year. In patients who are immunocompromised, oral administration of intravenous immune globulin is recommended.41

Infection with Giardia is limited to the small intestine and biliary tract. Children can present with intermittent watery diarrhea with abdominal pain, or they can experience protracted, intermittent, often debilitating disease characterized by foul-smelling stools with flatulence, abdominal distention, and anorexia. The disease can become chronic and can lead to weight loss, failure to thrive, and anemia. Asymptomatic infection is common. Humans are the main reservoir, although it has been found in the stool of dogs, cats, beavers, and other animals.42 These animals can contaminate water with stool containing cysts that are infectious for humans. People contract the disease by hand-to-mouth transfer of cysts from stool of an infected person or by ingestion of fecally contaminated water or food. Epidemics from person-to-person transmission occur in childcare centers and in institutions for people with developmental delays. Duration of cyst excretion can last for months. The disease can be spread for as long as the infected person excretes cysts. Identification of trophozoites or cysts in stool specimens, duodenal fluid, or small bowel tissues by direct microscopic examination by staining methods, enzyme immunoassay, or polymerase chain reaction makes the diagnosis. An examination of a single direct smear of stool has a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 95%. The sensitivity increases in diarrheal stools because they have a higher concentration of organisms. Looking at three or more specimens collected every other day can also increase sensitivity. Treatment includes correction of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities and antibiotics. Tinidazole, metronidazole, and nitazoxanide are the drugs of choice (see Table 173-4). If therapy fails, a course can be repeated with the same drug. Relapse is common in the immunocompromised host, who often requires prolonged treatment. Treatment of asymptomatic carriers is not recommended except in households with hypogammaglobulinemia or cystic fibrosis.43

E. histolytica can be found worldwide but is more prevalent in the lower socioeconomic population and in developing countries, where the prevalence of amebic infection may be as high as 50% in some communities. Immigrants from areas with endemic infection, institutionalized people, and men who have sex with other men are at increased risk for infection. People with intestinal amebiasis often have 1 to 3 weeks of increasingly severe diarrhea progressing to grossly bloody dysenteric stools with lower abdominal pain and tenesmus. Weight loss is common, but fever occurs in less than half of the patients. Symptoms can become chronic and may mimic inflammatory bowel disease. Complications include fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon, and ulceration of the colon and perianal area, rarely with perforation. Complications are more common in patients treated inappropriately with corticosteroids or antimotility drugs. E. histolytica is transmitted through amebic cysts by the fecal-oral route. Ingested cysts are unaffected by gastric acid. Infected persons who are untreated can excrete cysts for years. Transmission has also been associated with contaminated food and water. Sexual transmission may also occur. Identification of trophozoites or cysts in stool specimens secures the diagnosis. Examination of serial specimens is often necessary. Enzyme immunoassay test kits are also available for routine serodiagnosis of amebiasis. Treatment of asymptomatic cyst excreters is to provide them with a luminal amebicide such as iodoquinol, paromomycin, or diloxanide (see Table 173-4). Patients with mild to moderate or severe intestinal symptoms or extraintestinal disease (liver abscess) should be treated with metronidazole or tinidazole, followed by a course of luminal amebicide. Follow-up stool examination is recommended after completion of therapy because complete eradication of intestinal infection is difficult. Asymptomatic household members with stools positive for E. histolytica should also be treated.44

Clinical Features

Although acute diarrhea in children often results in self-limited mild disease, it can cause significant fluid and electrolyte abnormalities that can have serious consequences. Indications for medical evaluation of children with diarrhea have been proposed (Box 173-1). Serious illnesses may be overlooked on cursory examination. The principal goals of the ED evaluation are to identify and to correct fluid, electrolyte, acid-base, and nutrient deficits that may result from vomiting, diarrhea, or decreased oral intake and to determine which children would benefit from prolonged management.

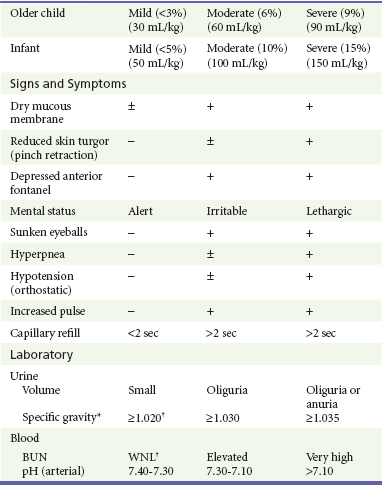

The physical examination should include close scrutiny of the vital signs while keeping in mind that clinical signs are often insensitive and nonspecific for dehydration.45 For example, tachycardia is sensitive but nonspecific because there are many other causes of tachycardia, such as fever and anxiety. On the other hand, hypotension is specific but insensitive because children usually will maintain adequate blood pressure until severe intravascular depletion occurs. The evaluation of the child should begin with looking at the child from across the room in a position of comfort, noting the patient’s overall appearance, responsiveness, activity, and work of breathing. A head-to-toe physical examination of the patient then should be performed, focusing on signs of dehydration (sunken eyes, dry mucous membranes, absence of tears, poor skin turgor, delayed capillary refill time). A general assessment of the abdomen and lungs should always be done to help rule out other pathologic processes. Clinicians often overestimate the extent of dehydration (see Table 173-5 for degree of dehydration). Clinical signs are usually not present until a child has lost at least 5% of his or her body weight. The three most useful signs in determining dehydration of more than 5% are prolonged capillary refill time, abnormal skin turgor, and abnormal respiratory pattern.45 Older children and adults may manifest symptoms at a lesser degree of volume depletion because of relatively smaller total body water and extracellular fluid volume.

Table 173-5

Clinical Assessment of Degree of Dehydration

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; WNL, within normal limits.

+, present; −, absent; ± variable.

*Specific gravity can provide evidence that confirms the physical assessment.

†Not usually indicated in mild or moderate dehydration.

From Barkin RM, Rosen P: Emergency Pediatrics, 5th ed. St Louis, Mosby, 1999.

Diagnostic Strategies

Children who present with mild disease often require no diagnostic testing. In children assessed to have significant dehydration from acute diarrhea with or without vomiting, serum electrolyte levels and glucose concentration should be assessed. The usefulness of laboratory testing to estimate hydration status has been evaluated in multiple studies. In general, these studies concluded that laboratory tests are helpful only when results are markedly abnormal, and none alone is considered definitive for dehydration.45–48

Although stool culture is not indicated in most cases of uncomplicated acute gastroenteritis, stool samples should be obtained for culture if specific therapy, hospitalization, or infection control measures may be indicated. Stool cultures should also be considered in patients with systemic involvement or underlying chronic medical complications or if the illness involves dysenteric (stool with mucus, blood, or both) features. In many hospital laboratories, a routine stool culture does not include testing for E. coli O157:H7.49 However, according to the CDC in 2009, all stools submitted for testing from patients with acute community-acquired diarrhea (i.e., for detection of the enteric pathogens Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter) should be cultured for O157 on selective and differential agar. These stools should also be simultaneously assayed for non-O157 STEC with a test that detects the Shiga toxins or the genes encoding these toxins.50 Therefore, for patients with suspected E. coli O157 infection (dysentery, diarrhea with tenesmus), one should specify to the laboratory as this culture is not routinely performed.

Differential Considerations

Vomiting in children is a common sign with an exhaustive list of causes. In addition to other usual causes of nausea, children may vomit in response to pain, anxiety, or fear. Some general and life-threatening causes of vomiting are presented in Table 173-1. Diarrhea also is a common reason for parents to bring their children to the ED. Most often, diarrhea is associated with other features of acute gastroenteritis, but it may be the sole presenting complaint. Table 173-2 presents a brief list of causes of diarrhea in children. An important point is that although most children with diarrhea or vomiting, or both, have a relatively benign cause of their illness, other, more sinister diagnoses should be considered and ruled out. This can often be done by careful history and physical examination.

Management

See also the next section on dehydration.

In addition to resuscitation of children in shock, the priorities in ED management of children with diarrhea are to consider and to rule out other potential causes of diarrhea other than infectious diarrhea; to assess for and treat underlying deficits and potential complications; to determine which patients require prolonged treatment or hospitalization; and, when necessary, to arrive at a microbiologic diagnosis. Table 173-4 lists the common infectious agents of diarrhea and the indicated treatment.

Antibiotics are not needed in viral gastroenteritis or in most cases of uncomplicated bacterial gastroenteritis. Cases that may require antimicrobial therapy are those with increased potential to develop complications. This population includes those with septicemia, immunosuppression, or chronic diseases; premature babies (<1 year), neonates, and young infants; and those with articular or valve prostheses. Antibiotics are also recommended for Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and amebic dysentery. The child with bloody diarrhea is at higher risk for complications, including sepsis and other systemic diseases; therefore, the threshold for admission of such children to the hospital for close observation is lower. Stool cultures are indicated in the setting of acute bloody diarrhea and are helpful to guide therapy. In the majority of cases, empirical antimicrobial agents should not be administered while culture results are awaited because antimicrobial therapy might not be indicated even when culture results are positive.51

There is evidence to support the use of probiotics, especially Lactobacillus GG (LGG), in acute infectious diarrhea in otherwise healthy infants and young children. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by Szymanski and colleauges,52 administration of LGG significantly shortened the duration of rotavirus diarrhea by a mean of 40 hours, but the duration of diarrhea of other causes was not affected. Results of other studies and a Cochrane review have indicated that probiotics reduce the number of diarrheal stools and the duration of diarrhea by approximately 1 day. These studies also reported that LGG is the most effective at doses greater than 1010 colony-forming units. It also appears that probiotics are more effective if they are given early in the course of the disease.52–56 Used alongside rehydration therapy, probiotics appear to be safe and have clear beneficial effects in shortening the duration of and reducing stool frequency in acute infectious diarrhea. However, studies do not agree on the type of probiotic or dosing at this time.

Zinc deficiency is common in developing countries and occurs in most parts of Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and south Asia. During the past 10 to 15 years, studies have shown that zinc supplementation given to children living in developing countries has decreased the duration and severity of diarrhea illness. The majority of zinc trials were conducted in countries at high risk for zinc deficiency, but those conducted at medium risk showed similar effect on duration and severity. On the basis of these findings, the World Health Organization endorses zinc supplementation for children with acute diarrhea (<6 months 10 mg/day, >6 months 20 mg/day for 10 to 14 days),57 despite the lack of data from studies in developed countries. Currently, Children’s Hospital in Boston is recruiting patients for a study on the effects of oral zinc in children with acute diarrhea in the United States.

Disposition

Most cases of childhood diarrhea can be managed on an outpatient basis by continuing routine formula or diet specific for age. Supplemental maintenance electrolyte solutions may be given. If home oral rehydration therapy is ordered, feeding should resume with an age-appropriate diet as soon as vomiting subsides. Routine fasting for diarrhea illnesses is not recommended. Before discharge from the ED, careful and specific instruction about the signs and symptoms of expected improvement or complications should be given to the parents or caregiver (Box 173-2). Instructions should address proper hygiene and handwashing techniques to prevent others from contracting the illness. Monitoring of handwashing in daycare facilities has been shown to reduce bacterial contamination in children. Follow-up by the patient’s primary care physician should be timely and should address concerns of worsening of the condition and complications that may have developed. Hospitalization should be considered in children at high risk for complications: children younger than 1 year, very-low-birth-weight infants, children with chronic medical problems, children with electrolyte abnormalities who require intravenous repletion, children with severe dehydration, and children with dysentery. Hospitalization may also be warranted in cases of protracted vomiting, diarrhea with losses in excess of fluid administration, worsening clinical status despite therapy, presence of an underlying condition that would complicate therapy, or suspected systemic involvement. Very-low-birth-weight infants, because of low physiologic reserve and immature immune system, are at the highest risk for complications of acute gastroenteritis in the first year of life.

Dehydration

Dehydration, or decrease in total body water, can be caused by a variety of mechanisms. Broadly speaking, however, mechanisms of dehydration represent three general categories: decreased intake, such as with stomatitis; increased output, such as with diarrhea and diabetes; and increased insensible losses, such as with fever. The severity of dehydration usually is measured as the acute weight (presumably fluid) loss as a percentage of pre-illness total body weight. Dehydration of more than 5% is considered significant and often can be identified by history and physical examination (see Table 173-5). Because pre-illness weights generally are not available or reliably reported, the clinician will need to rely on historical information, physical examination findings, and laboratory test results in assessing the severity of dehydration. Parental reports of history and observation are of significant value, with good sensitivity in detecting dehydration.58 In a child who is dehydrated, initial physical examination may reveal an activity level lower than expected for age. The child may appear weak or lethargic. If the fontanel is still open, it may be sunken. The eyes appear sunken and the mucous membranes are dry (if the child has recently had something to drink, the mucous membranes may falsely appear moist). Tachycardia and hyperpnea may be present. The skin over the trunk should be examined for tenting (suggesting hyponatremia) or a doughy texture (suggesting hypernatremia). It is important to keep in mind that clinical signs and symptoms of dehydration are variable and often subtle. The three most useful signs to determine dehydration of more than 5% are prolonged capillary refill time, abnormal skin turgor, and abnormal respiratory pattern.45

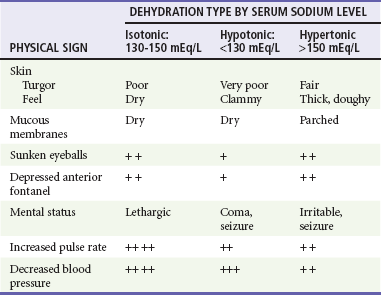

Laboratory tests may be helpful in assessing children for etiology, severity, and complications of dehydration. A serum electrolyte panel and BUN, serum creatinine, and blood glucose determinations are the tests most commonly ordered.59 Sodium concentration is important in identifying isonatremic, hyponatremic, and hypernatremic states for appropriate choice of therapy (Table 173-6). A low serum HCO3− level may indicate loss of HCO3− in the stool or may reflect poor tissue perfusion. Newer noninvasive techniques for detection of dehydration have been described, such as ultrasound assessment of inferior vena cava diameter60 and measurement of exhaled carbon dioxide as a marker for acidosis.61 Children with dysentery should have BUN and serum creatinine concentrations measured and stool culture specimens sent and examined for E. coli O157:H7 to identify potential cases of HUS. Serum glucose level is important because hypoglycemia is common in young children with viral gastroenteritis, and this test may help identify children with previously undiagnosed fatty acid oxidation disorders or other inborn errors of metabolism.

Table 173-6

Types of Dehydration Reflected by Serum Sodium Concentration

+, ++, +++, relative prominence of finding.

From Barkin RM, Rosen P: Emergency Pediatrics, 5th ed. St Louis, Mosby, 1999.

Differential Considerations

Most commonly, dehydration in children results from diarrhea and vomiting caused by infectious gastroenteritis. Table 173-7 lists some other causes of dehydration that should be considered when the gastrointestinal tract is not primarily involved.

Table 173-7

Differential Diagnosis of Volume Depletion

| FLUID LOSS CATEGORY | POTENTIAL ETIOLOGIC DISORDERS OR CONDITIONS |

| Renal | Diuretics, renal tubular acidosis, renal failure, urinary tract obstruction, diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, renal trauma, salt-wasting nephritis |

| Extrarenal | Third spacing (pancreatitis, peritonitis, sepsis), skin loss (burns, cystic fibrosis), lung loss, congestive heart failure, liver failure, hemorrhage |

Fluid and Electrolyte Management

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is a safe and effective treatment of infants and children with mild to moderate dehydration.62–65 ORT may be instituted even if the patient continues to vomit or has diarrhea. Children with severe dehydration, shock, lethargy, acute abdomen, suspected intestinal obstruction, sodium derangement, or significant underlying illness should be identified by means of a thorough history and physical examination and laboratory tests and be excluded from ORT. Some of these principles are illustrated in Box 173-3.

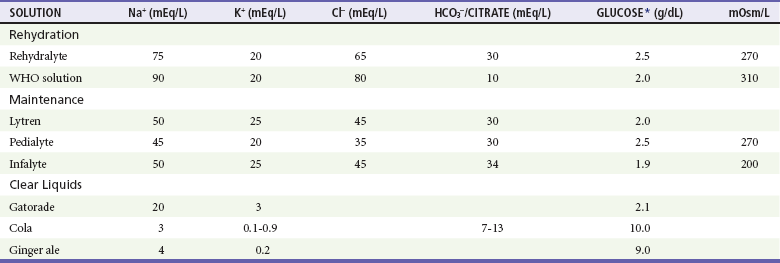

The ORT period in the ED may span 4 to 8 hours and provide an opportunity to educate the family in skills of evaluating and treating childhood diarrhea. A number of ORSs have been shown to be effective. The main ingredients are water, glucose, sodium chloride, and bicarbonate in various concentrations (Table 173-8). In most situations, rehydration can be accomplished without the risk of causing hyponatremia or hypernatremia.

Table 173-8

Common Oral Hydrating Solutions

*May be long-chain oligosaccharide subject to hydrolysis.

From Barkin RM, Rosen P: Emergency Pediatrics, 5th ed. St Louis, Mosby, 1999.

In infants and children with minimal dehydration, treatment should be directed at maintaining hydration and nutrition with an age-appropriate diet. Fluid intake should be increased, or ORS can be administered to cover maintenance and to replace losses. Losses can be replaced at 10 mL/kg for each stool and 2 mL/kg for each emesis. Diet should not be restricted.62

1. Estimate the degree of volume depletion as mild or moderate with information from the history, clinical signs, and physical examination findings (see Table 173-1).

2. Calculate the desired volume of ORS as 30 to 50 mL/kg for mild (3-5%) and 60 to 80 mL/kg for moderate (6-9%) volume depletion.

3. Administer 25% of the volume of ORS to be replaced each hour for the first 4 hours.

This technique requires that the ED have the facilities and personnel to observe and to monitor the patient for an extended time to determine the success or failure of ORT. The parent or other caregiver can be taught to administer ORT. Nursing personnel also should instruct the parent in observation skills, methods of administration of the fluid, and types of fluid that are considered appropriate for children with vomiting and diarrhea. During the monitoring period, a child who is unable to tolerate intake of the prescribed volume of fluid at the expected rate should receive intravenous fluids. It is important to determine whether the failure is the result of the child’s inability to ingest the fluid, excessive fluid loss through vomiting or diarrhea, or poor technique or motivation on the parent’s part. It usually is possible to maintain the fluid administration rate in children who continue to vomit by administering small volumes frequently. This may require, for instance, use of a spoon or syringe to slowly drip the fluid by hand. Some success has been obtained with the use of nasogastric tubes.66

In the last several years, ondansetron has become a useful adjunct in the treatment of acute gastroenteritis in the pediatric ED. Ondansetron, a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor antagonist, acts at chemoreceptors in the peripheral and central nervous system to alleviate nausea, which has been shown in numerous well-designed studies in children to reduce episodes of vomiting in the pediatric ED, to reduce the need for intravenous fluid rehydration, and to improve oral intake in the pediatric ED.67–71

Intravenous Therapy

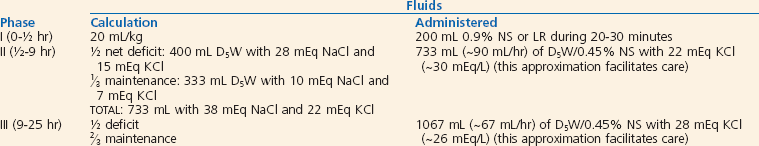

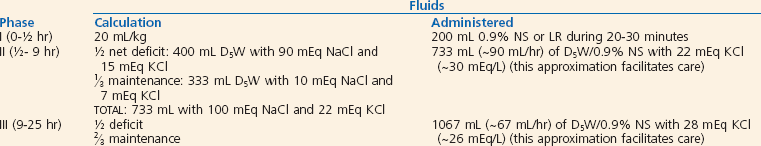

Patients are evaluated in accordance with their immediate (emergency phase, phase I), short-term (repletion phase, phase II), and long-term (early refeeding phase, phase III) needs.72 During the emergency phase, the aim of fluid resuscitation is to restore circulatory volume. This fluid needs to be administered rapidly to prevent imminent serious morbidity or death. During the repletion phase, fluid and electrolyte derangements are reversed, and ongoing losses are replaced. This phase lasts 24 hours. In the early refeeding phase, long-term needs are addressed in the next few days, during which the body recovers fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional homeostasis. Immediate and short-term therapies are initiated in the ED, with subsequent phases carried out in the inpatient setting or at home as managed by the primary care physician. In clinical practice, this algorithm represents a continuum of care and not three distinct, separate phases. Monitoring of serum electrolyte, BUN, and blood glucose concentrations is indicated for patients receiving intravenous fluid therapy.

Emergency Resuscitation Phase.72: Rapid reexpansion of the intravascular space is the goal of immediate resuscitation and can be achieved with an isotonic crystalloid solution. Administration of 20 mL/kg of 0.9% saline (or other appropriate isotonic crystalloid solution) intravenously at a rapid rate should result in reversal of signs of shock within 5 to 15 minutes. In critical situations, intraosseous routes should be used if venous access is not immediately available. Subcutaneous administration may be considered in resource-limited areas of the world as an alternative for rehydration when oral rehydration is not successful. Patients should be reevaluated periodically, and those with excessive deficits should receive repeated boluses of 20 mL/kg until clinical improvement occurs. Signs of recovery include normalization of blood pressure measurements, improvement of mental status, improvement of tachycardia and capillary refill time, and production of urine. Volume requirements greater than 60 mL/kg without signs of improvement warrant investigation for other conditions, such as septic shock, hemorrhage, capillary leak with third-space fluid sequestration, congestive heart failure, and toxic shock.

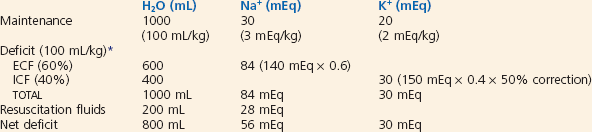

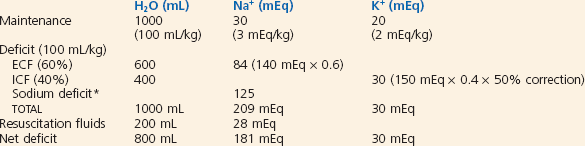

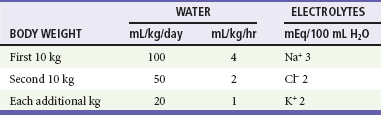

Repletion Phase.72: After immediate resuscitation, appropriate fluid therapy for the patient should be determined. Some patients may return to ORT after initial resuscitation. Calculations should take into account the fluids already administered and maintenance fluid (Table 173-9), and they should also accommodate changes in the patient’s clinical status. To allow accurate planning of the type and amount of fluid to be administered, volume replacement should proceed from the serum sodium level: hypernatremia (>150 mEq/L), hyponatremia (<130 mEq/L), or isonatremia (130-150 mEq/L).

Table 173-9

Maintenance Fluid and Electrolytes

Modified from Custer JW, Rau RE (eds): The Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers, 18th ed. Philadelphia, Mosby–Year Book, 2009.

Isonatremic Volume Depletion.72: Isonatremic volume depletion is the most common form of volume depletion and results from relatively equal losses of sodium and water. No change in body fluid tonicity or redistribution of fluid between the extracellular and intracellular fluid spaces occurs. This results in loss of fluid from the extracellular space and therefore intravascular volume depletion. Gastrointestinal fluid loss with or without decreased intake or increased urine loss is the most common cause. Repletion fluids are outlined for a sample patient in Box 173-4. In general, with use of 5% dextrose in 0.45% sodium chloride, half of the deficit fluids is given during the first 8 hours of repletion along with maintenance fluids. Potassium may be added to maintenance fluids once urine output is established and serum potassium levels are within a normal range. Continued losses (emesis, diarrhea) should also be replaced.

Hyponatremic Volume Depletion.72: Hyponatremic volume depletion is a result of loss of relatively more sodium than water, resulting in extracellular water shift into the intracellular fluid space to maintain equal osmolarity. This results in a significant decrease in intravascular volume and hemodynamic compromise. This type of volume depletion usually is caused by gastrointestinal fluid loss that has been replaced with hypotonic fluid. Specific signs and symptoms of hyponatremia are largely neurologic, ranging in severity from malaise and irritability to seizures and coma.

Appropriate management of hyponatremic dehydration for a sample patient is described in Box 173-5. If the serum sodium concentration is 120 to 130 mEq/L, 5% dextrose in 0.9% saline is administered, with half of the daily fluid requirement given in the first 8 hours and the remainder during the succeeding 16 hours. Monitoring of serum electrolyte values, BUN level, weight, and intake and output is recommended. Rapid correction of hyponatremia can be associated with central pontine myelinolysis. Close monitoring of serum sodium concentration is indicated, and the amount of sodium in the fluid is adjusted to maintain a slow correction. The target rate of rise of sodium is 2 to 4 mEq/L every 4 hours or 10 to 20 mEq/L in 24 hours.72 Potassium chloride, 20 mEq/L, is added to the intravenous fluids after renal function is assessed and urine output has been established. If the serum sodium concentration is less than 120 mEq/dL, the patient may exhibit seizures, hyperexcitability, or other neurologic symptoms. In such cases, 3% saline (sodium chloride 0.5 mEq/mL) should be administered as a bolus dose of 4 mL/kg. This dose will raise the serum sodium concentration by 3 to 4 mEq/L.

Hypernatremic Volume Depletion.72: Hypernatremic volume depletion (serum sodium level >150 mEq/L) arises with loss of relatively more water than sodium. It can occur if inappropriate types of fluids are given, if the fluid or formula is mixed incorrectly, or if fever or hyperventilation complicates the illness. This is the least common type of volume depletion because of a generally lower content of sodium in most modern infant fluids and formulas. Intracellular water shifts to the extracellular fluid space to maintain osmolar balance; therefore, intravascular volume is relatively preserved. Signs and symptoms specific to hypernatremia are doughy skin and altered central nervous system function (manifested as irritability, seizures, or high-pitched cry). Care should be taken not to administer hypotonic fluid at too fast a rate because water will equilibrate across the cerebral blood-brain barrier almost immediately (long before the sodium concentration is corrected), creating increased intracranial pressure. The most important goal is to reestablish intravascular volume and return serum sodium levels toward normal gradually (48-72 hours). After adequate volume expansion, rehydration fluids should be initiated with 5% dextrose in 0.2% to 0.45% sodium chloride at a slow rate during 48 to 72 hours. Serum sodium levels should be assessed every 4 hours. The goal is to reduce the serum sodium level at a rate of 0.5 to 1 mEq/L per hour.73 If the sodium level has decreased by less than 0.5 mEq/L per hour, sodium content of the rehydration fluid is decreased. This will allow a slow controlled correction of the hypernatremia. Box 173-6 provides guidelines for the calculation of fluids and electrolytes for a sample case. Close monitoring of neurologic status and serum electrolyte levels is important during the period of rehydration. It is imperative to remember to replace ongoing losses.

Hospital-Acquired Hyponatremia.: One of the complications that can develop during intravenous rehydration in children is acute hyponatremia. In children, this rare disturbance can lead to significant neurologic morbidity, including seizures, coma, and brain herniation or even death. For acute hyponatremia to occur, two conditions have to be met: (1) an exogenous source of free water must be available, and (2) secretion of antidiuretic hormone must occur. Many experts therefore recommend use of isotonic saline rather than hypotonic saline as the replacement intravenous fluid of choice in hospitalized children.74,75 This practice is not universally accepted.76 In any case, vigilance in monitoring of the neurologic status of children undergoing intravenous rehydration is essential.

References

1. Kosek, M, Bern, C, Guerrant, RL. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease, as estimated from studies published between 1992 and 2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:197.

2. Black, R, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: A systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1969.

3. Glass, RI, Lew, JF, Gangarosa, RE, LeBaron, CW, Ho, MS. Estimates of morbidity and mortality rates for diarrheal disease in American children. J Pediatr. 1991;118:527.

4. Fischer, TK, et al. Hospitalization and deaths from diarrhea and rotavirus among children <5 years of age in the United States, 1993 through 2003. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1117.

5. Maleck, MA, et al. Diarrhea- and rotavirus-associated hospitalizations among children less than 5 years of age: United States 1997 through 2000. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1187.

6. Widdowson, MA, et al. Cost-effectiveness and potential impact of rotavirus vaccination in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;119:684.

7. Lee, BP, et al. Nonmedical costs associated with rotavirus disease requiring hospitalization. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:984.

8. Klein, EJ, et al. Diarrhea etiology in a Children’s Hospital Emergency Department: A prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:807.

9. Lyman, WH, et al. Prospective study of etiologic agents of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks in childcare centers. J Pediatr. 2009;154:253.

10. Vernacchio, L, et al. Diarrhea in American infants and young children in community setting—incidence, clinical presentation, and microbiology. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:2.

11. Denno, DM, et al. Etiology of diarrhea in pediatric outpatient settings. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:142.

12. Widdowson, MA, Bresee, JS, Gentsch, JR, Glass, RI. Rotavirus disease and its prevention. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:26.

13. American Academy of Pediatrics. Rotavirus infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:576–579.

14. Dennehy, PH. Rotavirus vaccines: An update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005;17:88.

15. Cortese, MM, Parashar, UD. Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:1.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children. Recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:1.

17. Patel, MM, et al. Intussusception risk and health benefits of rotavirus vaccination in Mexico and Brazil. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2283.

18. Patel, MM, et al. Systematic literature review of role of norovirus in sporadic gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1224.

19. Glass, RI, Parashar, UD, Estes, MK. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1776.

20. American Academy of Pediatrics. Human calicivirus infections (norovirus and sapovirus). In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:241–242.

21. American Academy of Pediatrics. Astrovirus infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:225.

22. American Academy of Pediatrics. Adenovirus infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:204–206.

23. American Academy of Pediatrics. Salmonella infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:584–589.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS): Human Isolates Final Report, 2009. Atlanta, Ga: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

25. American Academy of Pediatrics. Shigella infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:593.

26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: Incidence and trends of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food—Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. sites, 1996-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:749.

27. American Academy of Pediatrics. Campylobacter infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:243–245.

28. Perdikogianni, C, et al. Yersinia enterocolitica infection mimicking surgical conditions. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:589.

29. American Academy of Pediatrics. Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:733–735.

30. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clostridium difficile. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:263–265.

31. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clostridium perfringens food poisoning. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:265–266.

32. American Academy of Pediatrics. Staphylococcal food poisoning. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:600–601.

33. American Academy of Pediatrics. Vibrio infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:727.

34. American Academy of Pediatrics. Escherichia coli diarrhea. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:294.

35. Ochoa, TJ, Cleary, TG. Epidemiology and spectrum of disease of Escherichia coli O157. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:259.

36. Nataro, JP. Escherichia coli. In Long S, Pickering LK, Prober CG, eds.: Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Disease, 3rd ed, Orlando, Fla: Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

37. Wong, CS, et al. The risk of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome after antibiotic treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1930.

38. Schering, J, Andreoli, SP, Zimmerhackl, LB. Treatment and outcome of Shiga-toxin–associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1749.

39. Safdar, N, Said, A, Gangnon, R, Maki, D. Risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome after antibiotic treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 enteritis. JAMA. 2002;288:996.

40. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cryptosporidiosis surveillance—United States, 2003-2005. MMWR Surveil Summ. 2007;56:1–10.

41. American Academy of Pediatrics. Cryptosporidiosis. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:272.

42. Hlavsa, MC, Watson, JC, Beach, MJ. Giardiasis surveillance—United States, 1998-2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2005;54:9–16.

43. American Academy of Pediatrics. Giardia intestinalis infections (giardiasis). In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:303.

44. American Academy of Pediatrics. Amebiasis. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:206.

45. Steiner, MJ, DeWalt, DA, Byerley, JS. Is this child dehydrated? JAMA. 2004;291:2746.

46. Gorelick, MH, Shaw, KN, Murphy, KO. Validity and reliability of clinical signs in the diagnosis of dehydration in children. Pediatrics. 1997;99:E6.

47. Duggan, C, et al. How valid are the clinical signs of dehydration in infants? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;22:56.

48. Emond, S. Dehydration in infants and young children. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:395.

49. Voetsch, AC, et al. Stool specimen practices in clinical laboratories, FoodNet sites, 1995-2000. In: International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002:94.

50. Gould, LH, et al. Recommendations for diagnosis of Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli infections by clinical laboratories. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:1.

51. King, CK, Glass, R, Bresee, JS, Duggan, C, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Managing acute gastroenteritis among children: Oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:9.

52. Szymaski, H, et al. Treatment of acute infectious diarrhoea in infants and children with a mixture of three Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:247–253.

53. Szajewska, H, Mrukowicz, JZ. Probiotics in the treatment and prevention of acute infectious diarrhea in infants and children: A systematic review of published randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33(Suppl 2):S17–S25.

54. Van Niel, CW, Feudtner, C, Garrison, MM, Christakis, DA. Lactobacillus therapy for acute infectious diarrhea in children: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2002;109:678.

55. Huang, JS, Bousvaros, A, Lee, JW, Diaz, A, Davidson, EJ. Efficacy of probiotic use in acute diarrhea in children: A meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2625.

56. Allen, SJ, Okoko, B, Martinez, E, Gregorio, G, Dans, LF. Probiotics for treating infectious diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (11):2010.

57. WHO/UNICEF Joint Statement. Clinical Management of Acute Diarrhoea. Geneva: The United Nations Children’s Fund/World Health Organization; 2004.

58. Porter, SC, Fleisher, GR, Kohane, IS, Mandl, KD. The value of parental report for diagnosis and management of dehydration in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:196.

59. Wathen, JE, MacKenzie, T, Bothner, JP. Usefulness of the serum electrolyte panel in the management of pediatric dehydration treated with intravenously administered fluids. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1227.

60. Chen, L, Kim, Y, Santucci, KA. Use of ultrasound measurement of the inferior vena cava diameter as an objective tool in the assessment of children with clinical dehydration. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:841.

61. Nagler, J, Wright, R, Krauss, B. End-tidal carbon dioxide as a measure of acidosis among children with gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2006;118:260.

62. King, CK, et al. Managing acute gastroenteritis among children: Oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:1.

63. Fonseca, BK, Holdgate, A, Craig, JC. Enteral vs intravenous rehydration therapy for children with gastroenteritis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:483.

64. Hartling, L, et al. Oral versus intravenous rehydration for treating dehydration due to gastroenteritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2006.

65. Spandorfer, PR, Alessandrini, EA, Joffe, MD, Localio, R, Shaw, KN. Oral versus intravenous rehydration of moderately dehydrated children: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2005;115:295.

66. Nager, AL, Wang, VJ. Comparison of nasogastric and intravenous methods of rehydration in pediatric patients with acute dehydrations. Pediatrics. 2002;109:566.

67. Freedman, SB, Adler, M, Seshadri, R, Powell, EC. Oral ondansetron for gastroenteritis in a pediatric emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1698.

68. Ramsook, C, Sahagun-Carreon, I, Kozinetz, CA, Moro-Sutherland, D. A randomized clinical trial comparing oral ondansetron with placebo in children with vomiting from acute gastroenteritis. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:397.

69. Alhashimi, D, Al-Hashimi, H, Fedorowicz, Z. Antiemetics for reducing vomiting related to acute gastroenteritis in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2009.

70. Roslund, G, Hepps, TS, McQuillen, KK. The role of oral ondansetron in children with vomiting as a result of acute gastritis/gastroenteritis who have failed oral rehydration therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:22.

71. Stork, CM, Brown, KM, Reilly, TH, Secreti, L, Brown, LH. Emergency department treatment of viral gastritis using intravenous ondansetron or dexamethasone in children. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1027.

72. Custer JW, Rau RE, eds. The Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers, 18th ed, Philadelphia: Mosby–Year Book, 2009.

73. Androgue, HJ, Madias, NE. Hypernatremia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1493.

74. Hoorn, EJ, et al. Acute hyponatremia related to intravenous fluid administration in hospitalized children: An observational study. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1279.

75. Moritz, ML, Ayus, JC. Prevention of hospital-acquired hyponatremia: A case for using isotonic saline. Pediatrics. 2003;111:227.

76. Holliday, MA, et al. Acute hospital-induced hyponatremia in children: A physiologic approach. J Pediatr. 2004;145:584.