Infectious Causes of Liver Disease

Viral hepatitis is the most common diffuse infection of the liver in otherwise healthy children.1 Although parasites are more common worldwide, they typically involve the biliary tree, as in ascariasis, or produce focal infections of the liver, as in echinococcosis or amebiasis. In immunocompromised patients, other infections, particularly fungal infections, become more common.

Viral Hepatitis

Overview: Viral hepatitis presents a spectrum of clinical severity, which can range from subclinical infections to fulminant hepatitis or progression into cirrhosis.

Etiology: Beyond the neonatal period, viral hepatitis is most commonly caused by the hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C viruses.1 A number of other viruses have been implicated in childhood hepatitis, including mumps, measles, varicella-zoster, herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, Coxsackie virus, and Epstein-Barr virus. Most affected patients have a short-lived acute disease with complete recovery. Complications include subacute and chronic active hepatitis, evolution into cirrhosis, and development of hepatocellular carcinoma.2

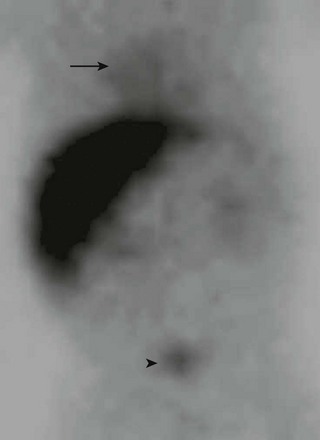

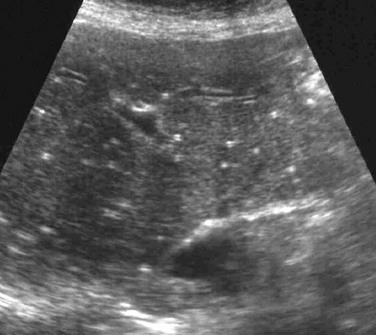

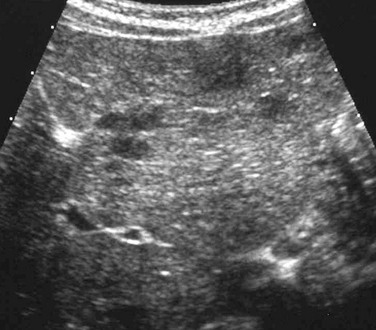

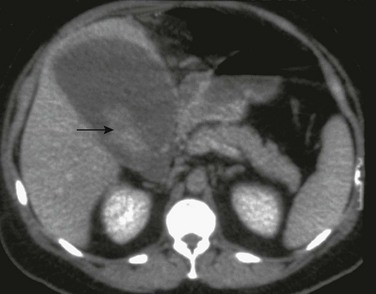

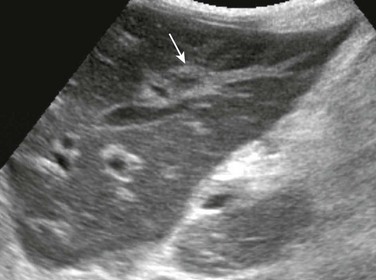

Imaging: Diagnosis is made clinically and on the basis of laboratory data. If imaging is performed during the acute phase of the illness, the liver may be enlarged or normal in size. Sonography of the affected liver may demonstrate increased parenchymal echogenicity and heterogeneity.3 Increased thickness of the portal triads related to periportal edema may be seen (Fig. 91-1), which leads to the “starry sky” pattern, and the gallbladder wall can appear thickened.1,4–6 Lymphadenopathy may be present at the porta hepatis. Computed tomography (CT) scans sometimes show heterogeneous changes in attenuation, but more commonly they show hepatomegaly, gallbladder wall thickening, and periportal low attenuation (Fig. 91-2). In patients with fulminant hepatitis and subsequent hepatic regeneration, imaging differences have been described between necrotic areas and regenerating nodules. Regions of necrosis have central low attenuation on noncontrast CT relative to regions of regeneration. After intravenous (IV) administration of contrast material, areas of necrosis and regeneration may enhance similarly such that they become indistinguishable, or the regenerating nodules may show diminished enhancement, which can simulate a neoplastic lesion. Similarly, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show nonspecific periportal high intensity on T2-weighted images and hepatomegaly.3 On MRI, areas of nodular regeneration show high signal on T1-weighted images and low signal on T2-weighted images relative to adjacent parenchyma.4

Figure 91-1 Periportal edema in a 12-year-old boy with viral hepatitis.

A longitudinal sonogram demonstrates increased perivascular echogenicity along the portal triads (arrow).

Figure 91-2 Gallbladder wall thickening in a 10-year-old boy with viral hepatitis.

A, A longitudinal sonogram shows a thick, hyperechoic gallbladder wall (arrows). B, Computed tomography with intravenous contrast confirms gallbladder wall thickening (arrows) and periportal edema.

Although it is used less frequently today than in the past, nuclear scintigraphy may be performed in infants suspected of having biliary atresia or hepatitis. Because liver function is decreased, there is poor uptake of the radiopharmaceutical agent with delayed excretion through the biliary tree into the small bowel and vicarious excretion through the kidneys (Fig. 91-3).

Pyogenic Abscess

Overview: Pyogenic infection with hepatic abscess formation is caused by microbial liver infection with subsequent inflammatory cell response and pus accumulation. The mortality rate is 6% to 14%.5 Immunocompromised patients with chronic granulomatous disease of childhood or those who have undergone bone marrow transplantation are at particularly high risk for liver abscesses. Other susceptible states include chemotherapy, congenital or acquired immunodeficiency, and intraabdominal infection, such as appendicitis and inflammatory bowel disease.2 Hepatic abscesses are most common in the right hepatic lobe, and most are solitary.6

Etiology: Staphylococci, streptococci, and Escherichia coli are the most common pathogens involved in a pyogenic abscess. However, Klebsiella pneumonia, which typically is more common in Asian countries, is increasing in incidence in North America.6,7

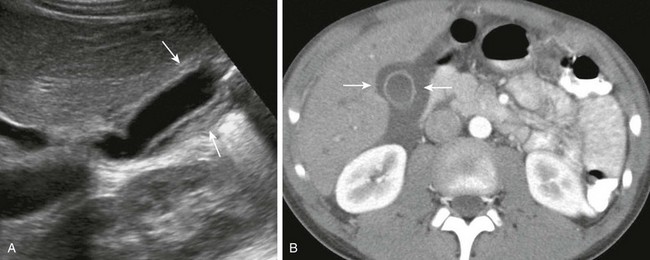

Imaging: Hepatic abscesses often have an insidious presentation, leading to a delay in diagnosis. They range from single, well-defined, homogeneous, circular foci to heterogeneous, poorly defined, multiloculated, septated, debris- or gas-containing lesions (Fig. 91-4). Air-fluid levels may be related to gas-forming organisms. Enhanced through-transmission in a hypoechoic mass on ultrasound and lack of central flow with Doppler are useful in confirming a cystic, rather than a solid, lesion.2 Other sonographic findings in persons with a pyogenic liver abscess include a hypoechoic or anechoic mass, a hypoechoic surrounding ring of edema, internal fluid-debris levels, and septations. Common CT findings include lack of central enhancement after contrast administration, an enhancing abscess wall, and a surrounding rim of low-attenuation hepatic edema.2,8 Abscesses in patients with chronic granulomatous disease may heal with formation of granulomas, which frequently calcify. MRI of hepatic abscesses typically show decreased or nearly isointense signal on T1-weighted images, increased signal on T2-weighted images, and peripheral ringlike contrast enhancement.8 Multiple abscesses are most commonly the result of biliary disease, biliary obstruction, or hepatic trauma. Hematogenous spread of pyogenic organisms may result in multiple abscesses (Fig. 91-5). A tuberculous abscess cannot be differentiated on imaging studies from other pyogenic infections.9 Resolved tuberculosis may result in hepatic calcifications.

Figure 91-4 Pyogenic abscess in a 2-month-old boy with fever.

A, A longitudinal sonogram of the right hepatic lobe reveals a hypoechoic region with irregular margins (arrow) and a halo of decreased parenchymal echogenicity. B, Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography image confirms the low attenuation region. Staphylococcus was found upon subsequent percutaneous needle aspiration.

Treatment and Follow-up: Treatment of pyogenic abscesses ranges from antibiotics alone for small lesions (usually <5 cm) to percutaneous aspiration and catheter drainage for larger lesions. Percutaneous abscess drainage has markedly reduced case mortality from 40% to 2%.2,5,10 Because amebic abscesses are readily treated medically, serology or aspiration diagnosis of this entity can help avoid drain placement.11,12 The techniques used for percutaneous drainage in children are similar to those used for adults, although IV sedation or general anesthesia may be necessary.13 The rare complications that occur after percutaneous drainage include bleeding, peritonitis, and less often, septicemia, pneumothorax, and empyema.2 Surgical drainage is used only if catheter drainage fails or treatment of an underlying cause of abscess is required.11

Fungal Infections

Overview: Fungal infection occurs frequently in the setting of immune compromise, such as leukemia and chronic granulomatous disease; a reported increase in systemic fungal infection may be the result of longer survival of immunocompromised hosts.14,15

Etiology: The most common causative organism is Candida albicans, which may affect any organ system. However, other ubiquitous fungi such as Aspergillus, Histoplasma, Coccidioides immitis (in endemic areas), and opportnistic bacteria such as Nocardia have been identified in persons with immune compromise.14

Imaging: The imaging appearance depends on the host’s immune response. In neutropenic patients, disease is microscopic and lesions may be occult on imaging. Formation of microabscesses is possible when the patient recovers from neutropenia and mounts an immune response. On sonography, four imaging patterns of candidiasis within the liver are reported. All four patterns have multiple, small (<3 mm to 4 mm) lesions scattered diffusely throughout the liver parenchyma.16 Early in the disease process, the “wheel-within-a-wheel” appearance is seen, representing a hyperechoic nidus of necrotic fungus, surrounded by echogenic inflammatory cells, in turn surrounded by a peripheral zone of fibrosis. The bull’s-eye or target appearance, consisting of an echogenic center with a hypoechoic rim, is seen when the host mounts an immune response.2 The most common appearance is seen later and consists of diffuse uniform hypoechoic foci throughout the liver resulting from formation of tiny microabscesses (<4 mm) and fibrosis (Fig. 91-6). Last is the pattern of calcified, hyperechoic tiny foci in persons with a healed or healing fungal infection (1 to 4 mm) (Fig. 91-7).16,17 Findings on CT include multiple foci of low attenuation of variable size (2 to 20 mm), with or without enhancement and calcification.2,16 Arterial phase scans have been shown to be more sensitive for detection.18 MRI may reveal tiny lesions of low signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging and high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging; T1-weighted gradient echo sequences have been reported to show greater sensitivity than the spin-echo sequence.19 However, the appearance remains relatively nonspecific compared with the more distinct patterns described on sonography.16

Cat Scratch Disease

Overview: Cat scratch disease usually is a self-limited infection that most often involves the lymph nodes. In 5% to 10% of cases it spreads systemically to variably involve the liver, spleen, bone, and, rarely, the central nervous system with meningoencephalitis or neuroretinitis. Patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome may present with bacillary angiomatosis.20,21 Children usually present with painful lymphadenopathy; however, systemic spread may cause low-grade fever and various complaints related to involvement of virtually any organ system.20 The typical course of cat-scratch disease involves formation of granulomas, which heal spontaneously and may calcify.

Etiology: Cat scratch disease is caused by Bartonella henselae. The disease is transmitted to the patient’s lymphatic system, often by a cat scratch; occasionally the disease may be transmitted to humans via a flea or tick.20 It is helpful to elicit a history of recent contact or exposure to a cat or kitten in making the diagnosis. The organism is difficult to culture, and diagnosis hinges on enzyme assay for identification of anti-B. henselae immunoglobulins.22 A definitive diagnosis requires biopsy to detect deoxyribonucleic acid from the organism; however, a biopsy is rarely performed.

Imaging: Sonography of a patient with cat scratch disease reveals numerous small hypoechoic, well-marginated, circular, homogeneous foci within the liver or spleen, in many cases associated with lymphadenopathy (Fig. 91-8). On CT, small low-attenuation lesions are found before administration of contrast material. Variable attenuation is seen after administration of contrast material, and marginal enhancement often is present.23

Parasitic Infestations

Overview: Although rare in North America, ascariasis is estimated to affect 1 billion people worldwide; it is most prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in areas with poor sanitation.24

Etiology: Ascariasis is an intestinal infection caused by Ascaris lumbricoides. It occurs when eggs are ingested and grow into larvae and subsequently into pencil-shaped round worms within the intestine. Larvae that penetrate through the intestinal wall enter the bloodstream and travel to the liver and may continue on to the lungs. Symptoms depend on the organ involved. The helminthic mass within the lumen of the bowel may lead to intestinal obstruction and segmental volvulus.24 Worms may obstruct the biliary system, causing dilation and pain, as well as increasing the risk for bacterial superinfection.25

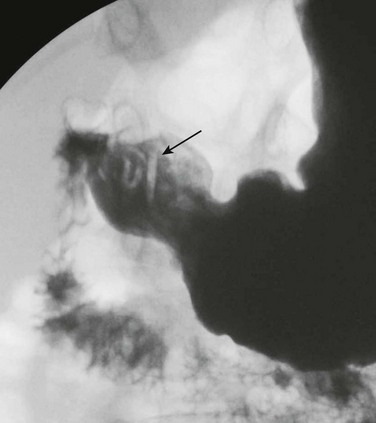

Imaging: On imaging studies, characteristic vermiform defects are seen inside the small intestine (Fig. 91-9), and if a small bowel follow-through is performed, the worms may ingest the contrast material, thus outlining their own gastrointestinal tracts.26 The worms can be visible on sonography, within the bowel lumen, or within the biliary tree.24,25

Echinococcosis

Overview: Echinococcosis or hydatid disease is a parasitic infection endemic in many parts of the world, with the major endemic regions encompassing sheep-grazing countries of the Mediterranean, Middle East, South America, and Australia. Although human disease most often affects the liver, multiple other organs may be affected, including the lung, peritoneum, genitourinary system, heart, and central nervous system.

Etiology: Hydatid disease refers to an infestation by the larval form of two main varieties of Echinococcus: E. granulosus and E. multilocularis. E. granulosus is more common, whereas E. multilocularis is more invasive.27 The definitive hosts are specific carnivores, such as the dog or wolf; ruminants, particularly sheep, are intermediate hosts, and humans are accidental intermediate hosts.28 Humans become infected by ingesting the parasite eggs in food or water contaminated with fecal material from the definitive host. After ingestion, the protective covering of the eggs is digested, releasing the larvae or oncosphere, which pass through the mucosa into the portal venous radicles, becoming lodged in the liver, where they may die or slowly grow to produce hydatid cysts.16,27 E. granulosus forms a cyst with three histologic layers. The outermost layer, the pericyst, is a tough, collagenous membrane formed by the host response to the parasite; the middle layer is an acellular membrane that allows the passage of nutrients; and the inner layer is the germinal layer, which secretes both the middle layer and cyst fluid. The germinal layer and the middle layer together are known as the endocyst, although the middle layer is sometimes termed the ectocyst. The germinal layer is the layer from which brood capsules and scolices are secreted into cyst fluid, forming “hydatid sand.” Daughter cysts may arise from brood capsules along the periphery of the endocyst.29 Formation of multiple daughter cysts may result in starvation and death of the cyst. When contained cyst rupture occurs, separation of the endocyst from the pericyst occurs, resulting in a floating membrane (water lily sign); communicating rupture, on the other hand, results in spillage of cyst material into the biliary tree, whereas direct rupture into the peritoneal cavity will lead to spillage of both infectious scolices and antigenic cyst fluid, causing seeding of the peritoneum and possibly anaphylaxis.2,27,28 Superinfection occurs only after cyst rupture, because the intact ectocyst is resistant to bacterial invasion.30

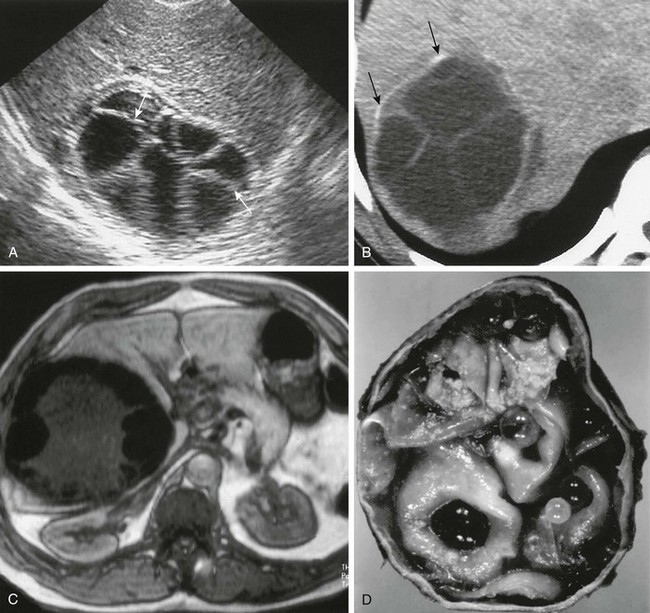

Imaging: The imaging appearance of E. granulosus and E. multilocularis is distinct. Hydatid cysts may be single or multiple; the right lobe is most commonly involved.2

Echinococcal cysts have been classified into three types, reflecting cyst contents and findings during various stages of development.28 Type I cysts are simple fluid-filled cysts that may contain hydatid sand and septa but exhibit no other internal architecture. On ultrasound they are anechoic, but upon rolling the patient, hydatid sand is dispersed, resembling “falling snowflakes.”27 On CT, type I cysts are well-defined hypodense lesions with enhancement of the cyst wall and any internal septa. At MRI, the signal intensity follows water, although on T2 weighting, the cyst may manifest a rim of low signal intensity.27 Type II cysts contain daughter cysts or internal matrix (Fig. 91-10). Ultrasound may demonstrate floating membranes or vesicles, and a “wheel spoke” appearance may arise from contact of multiple daughter cysts. On CT, the fluid within the mother cyst is of higher attenuation than that within the daughter cysts and may appear as a “rosette.” They may have scattered calcifications (Fig. 91-11). On MRI the membranes have low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences.27 Type III cysts are completely calcified and indicate cyst death.27,28

Figure 91-10 Echinococcal (hydatid) cyst.

A, A longitudinal hepatic sonogram shows a type II, well-defined (arrows), multilocular lesion with a “spoke wheel” appearance. B, An axial unenhanced computed tomography image confirms a mass with multiple septations, daughter cysts, and peripheral calcifications (arrows). C, An axial T1-weighted gradient echo magnetic resonance image shows a hepatic hydatid cyst with a hypointense fibrous pericyst and extensive peripheral low-signal-intensity daughter cysts surrounding central intermediate-signal-intensity matrix that was bright on T2-weighted images (not shown). D, A gross specimen of a resected hydatid cyst reveals numerous daughter cysts. (From Mortele KJ, Segatto E, Ros PR. The infected liver: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:937-955.)

Figure 91-11 An echinococcal (hydatid) cyst.

Axial unenhanced computed tomography images show peripheral calcification in hepatic echinococcal cyst (arrow).

E. multilocularis (alveolaris), which is less common than E. granulosus, is distributed in North America and central and northern Eurasia, with foxes and rodents serving as the definitive and intermediate hosts.31 The lesion grows by extension along its periphery, causing multilocular cysts as it invades the host tissues; central necrosis and calcification may be present. Its growth has been likened to that of a slow-growing tumor, with infiltration of biliary and venous structures within the liver.32 Imaging features of E. multilocularis include hepatomegaly, multiple irregular lesions with increased echogenicity on sonography, decreased attenuation on CT, microcalcifications and dilation of intrahepatic bile ducts, vascular involvement, and involvement of parahepatic structures by direct of hematogenous extension.31

Treatment and Follow-up: In general, treatment of echinococcal cysts requires removal of the entire cyst and its contents. Partial capsectomy may be done but has the drawback of increased risk of recurrence. Percutaneous drainage, injection, and reaspiration often is successful and is applied in conjunction with antiechinococcal drugs, particularly albendazole. However, the diagnosis of echinococcal cysts should be made serologically before percutaneous drainage because the differential diagnosis includes uncomplicated amebic and small pyogenic abscesses, which are treated with medical therapy alone.33 Inoperable cases or cases with disseminated disease may benefit from administration of albendazole.33,34

Amebic Abscess

Overview: Amebic infection is considered a leading parasitic cause of human mortality, affecting approximately 50 million people and resulting in 100,000 deaths annually.12,35 Endemic areas include Africa, India, the Far East, and South America.36 In the United States, about 1200 cases occur per year. With the availability of effective treatment, mortality from hepatic amebic abscess has gradually diminished from 2.0% to 0.2%.12

Amebic abscesses usually are solitary and often are found within the right lobe of the liver. The primary infection is often intestinal, with diarrhea and dysentery at presentation. The liver may become involved as a result of spread via the portal vein; however, some studies report that in 59% of cases there is no preceding history of diarrhea.37,38 Extension across the diaphragm to involve the pleura may occur. Other extraintestinal sites include pericardium, brain, skin, and genital disease, but involvement at these sites is rare.12,38 Perforation into the peritoneum will lead to peritoneal spread.38

Amebic abscesses can occur at any age but are most common in children younger than 3 years.36 The presentation is usually acute right upper quadrant pain. Diagnosis can be made from fresh stool specimens collected from at least three separate bowel movements. Circulating antibodies can be identified with serologic tests at least 7 days after invasive disease has presented.12

Imaging: The cross-sectional imaging appearance of amebic abscesses is variable and shares imaging features with pyogenic abscess. Sonography, the initial modality of choice, reveals a homogeneous round or oval mass with internal debris.11,36 Lesions are more common in the right lobe of the liver, are often peripheral in location near the hepatic capsule, and have enhanced through-transmission. CT shows a low attenuation area with peripheral enhancement and a rim, or halo, of surrounding edema and may show internal septations (Fig. 91-12).2 MRI of amebic abscesses shows heterogeneous low signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences and high signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences with a double-layered wall and peripheral enhancement after gadolinium administration.2

Treatment and Follow-up: Treatment of amebic abscesses is medical, in distinction to pyogenic abscesses, which generally require percutaneous or surgical drainage. More than 90% of patients do well with prolonged antibiotic therapy (usually metronidazole). The initial response to antibiotics is generally rapid, and failure to respond in 24 to 72 hours may indicate superimposed bacterial infection, in which case percutaneous aspiration may be useful.2 Percutaneous aspiration also may be useful if impending rupture is an immediate clinical concern.

Schistosomiasis

Overview: Schistosomiasis affects more than 250 million people worldwide, and approximately 600 million people are believed to be at risk for infection. The disease is endemic in South America, Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East and is rare in North America.39,40

Etiology: Schistosomiasis is an infection with parasitic blood flukes. Three forms affect humans: Schistosoma japonicum, Schistosoma mansoni, and Schistosoma hematobium.41 The latter affects the urinary system and will not be detailed in this chapter. The parasites penetrate the skin of humans (the definitive host) through contact with contaminated water, in which the intermediate host (a snail) releases the infective cercaria. The larvae mature and migrate to the venules of the urinary bladder (S. hematobium) or gastrointestinal tract (S. mansoni and S. japonicum) to deposit eggs. Eggs deposited in the gastrointestinal tract spread via the mesenteric venules to the portal vein, where they incite an inflammatory granulomatous response, resulting in fibrosis and presinusoidal portal obstruction.2

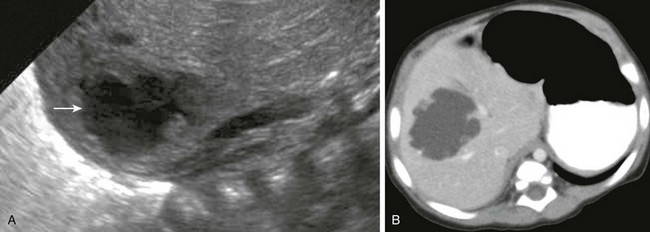

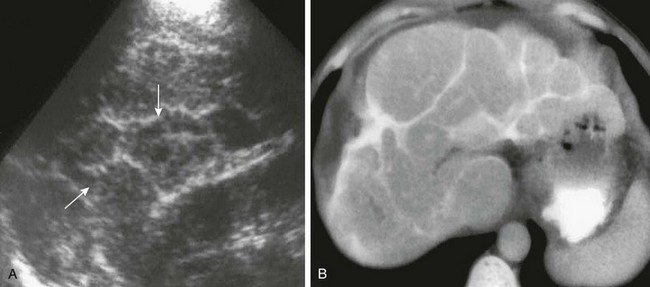

Imaging: The acute syndrome, also known as Katayama fever, can be suspected in persons who travel to endemic areas. Acutely, hepatosplenomegaly and hypoechoic lesions have been described in the liver, along with portal adenopathy.42 Chronic schistosomiasis demonstrates the changes of hepatic fibrosis and portal hypertension. The smaller eggs of S. japonicum are deposited along the small portal radicles at the periphery of the liver, whereas the larger S. mansoni eggs are deposited along the large portal branches from the liver hilum. Periportal fibrosis in persons with S. japonicum therefore is distributed along the peripheral part of the liver and centrally in patients infected with S. mansoni. Fibrotic tracts in patients with S. japonicum form a “polygonal network” with a honeycomb or tortoise shell appearance and are likely to calcify. Fibrotic tracts in patients with S. mansoni do not tend to calcify and form a “Symmers’ pipe-stem” fibrosis (Fig. 91-13).39,42 Sonography reveals hyperechoic septa outlining polygonal areas that may resemble a fish scale network. On CT, dense fibrous and calcific septa distributed at right angles to the hepatic surface produce the classic CT appearance of “turtle back calcification” in persons with S. japonicum infection. MRI may show isointense periportal bands on T1-weighted images, which are bright on T2-weighted images and enhance after gadolinium contrast administration.2,41

Figure 91-13 Schistosomiasis, Schistosoma japonicum.

A, A longitudinal sonogram of the right lobe of the liver reveals hyperechoic septations (arrows) between polygonal areas of hepatic parenchyma. B, An axial computed tomography image of the liver confirms the characteristic “turtle back” or “tortoise shell” appearance of the liver resulting from septal fibrosis with calcification. (From Mortele KJ, Segatto E, Ros PR. The infected liver: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:937-955.)

Treatment and Follow-up: Schistosomiasis infection is treatable with praziquantel.41 However, hepatic fibrosis related to egg antigens trapped in the liver occurs in approximately 20% of infected patients despite effective treatment, and work continues to identify the patients at greatest risk of the development of hepatic fibrosis.43

Balci, NC, Sirvanci, M. MR imaging of infective liver lesions. Magn Reson Imaging Clin North Am. 2002;10:121–135.

Doyle, DJ, Hanbidge, AE, O’Malley, ME. Imaging of hepatic infections. Clin Radiol. 2006;61(9):737–748.

Oleszczuk-Raszke, K, Cremin, FJ, Fisher, RM, et al. Ultrasonic features of pyogenic and amoebic hepatic abscesses. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;19:23.

Pedrosa, I, Saiz, A, Arrazola, J, et al. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics. 2000;20(3):795–817.

Restrepo, RS, Raut, AA, Riascos, R, et al. Imaging manifestations of tropical parasitic infections. Semin Roentgenol. 2007;42:37–48.

References

1. Gubernick, JA, Rosenberg, HK, Llaslan, H, et al. US approach to jaundice in infants and children. Radiographics. 2000;20(1):173–195.

2. Mortele, KJ, Segatto, E, Ros, PR. The infected liver: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24(4):937–955.

3. Itoh, H, Sakai, T, Takahashi, N, et al. Periportal high intensity on T2-weighted MR images in acute viral hepatitis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16(4):564–567.

4. Murakami, T, Baron, RL, Peterson, MS. Liver necrosis and regeneration after fulminant hepatitis: pathologic correlation with CT and MR findings. Radiology. 1996;198(1):239–242.

5. Yu, SC, Ho, SS, Lau, WY, et al. Treatment of pyogenic liver abscess: prospective randomized comparison of catheter drainage and needle aspiration. Hepatology. 2004;39(4):932–938.

6. Cerwenka, H, Bacher, H, Werkgartner, G, et al. Treatment of patients with pyogenic liver abscess. Chemotherapy. 2005;51(6):366–369.

7. Lederman, ER, Crum, NF. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):322–331.

8. Weissleder, R, Saini, S, Stark, DD, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess: contrast-enhanced MR imaging in rats. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150(1):115–120.

9. Essop, AR, Segal, I, Noormohamed, N. Tuberculous abscess of the liver. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1983;63(21):825–826.

10. Sharma, N, Sharma, A, Varma, S, et al. Amoebic liver abscess in the medical emergency of a North Indian hospital. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:21.

11. Barnes, PF, De Cock, KM, Reynolds, TN, et al. A comparison of amebic and pyogenic abscess of the liver. Medicine (Baltimore). 1987;66(6):472–483.

12. Kimura, K, Stoopen, M, Reeder, MM, et al. Amebiasis: modern diagnostic imaging with pathological and clinical correlation. Semin Roentgenol. 1997;32(4):250–275.

13. Liao, WI, Tsai, SH, Yu, CY, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess treated by percutaneous catheter drainage: MDCT measurement for treatment outcome. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(4):609–615.

14. Miller, JH, Greenfield, LD, Wald, BR. Candidiasis of the liver and spleen in childhood. Radiology. 1982;142(2):375–380.

15. Abelson, JA, Moore, T, Bruckner, D, et al. Frequency of fungemia in hospitalized pediatric inpatients over 11 years at a tertiary care institution. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):61–67.

16. Grünebaum, M, Ziv, N, Kaplinsky, C, et al. Liver candidiasis. The various sonographic patterns in the immunocompromised child. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21(7):497–500.

17. Yang, JJ, Lin, LW, Lin, ZH, et al. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of hepatic fungal infection. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7(2):169–173.

18. Metser, U, Haider, MA, Dill-Macky, M, et al. Fungal liver infection in immunocompromised patients: depiction with multiphasic contrast-enhanced helical CT. Radiology. 2005;235(1):97–105.

19. Boll, DT, Merkle, EM. Diffuse liver disease: strategies for hepatic CT and MR imaging. Radiographics. 2009;29(6):1591–1614.

20. Klotz, SA, Ianas, V, Elliott, SP. Cat-scratch disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(2):152–155.

21. Margileth, AM. Cat scratch disease. Adv Pediatr Infect Dis. 1993;8:1–21.

22. Giladi, M, Kletter, Y, Avidor, B, et al. Enzyme immunoassay for the diagnosis of cat-scratch disease defined by polymerase chain reaction. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(11):1852–1858.

23. Hopkins, KL, Simoneaux, SF, Patrick, LE, et al. Imaging manifestations of cat-scratch disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166(2):435–438.

24. Bahú Mda, G, Baldisserotto, M, Custodio, CM, et al. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic complications of ascariasis in children: a study of seven cases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33(3):271–275.

25. Akata, D, Ozmen, MN, Kaya, A, et al. Radiological findings of intraparenchymal liver Ascaris (hepatobiliary ascariasis). Eur Radiol. 1999;9(1):93–95.

26. Herlinger, H. Parasitic and bacterial inflammatory diseases. In: Herlinger H, Birnbaum B, eds. Imaging of the small intestine. New York: Springer Verlag, 1999.

27. Polat, P, Kantarci, M, Alper, F, et al. Hydatid disease from head to toe. Radiographics. 2003;23(2):475–494. [quiz 536-537].

28. Lewall, DB. Hydatid disease: biology, pathology, imaging and classification. Clin Radiol. 1998;53(12):863–874.

29. Pedrosa, I, Saíz, A, Arrazola, A, et al. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics. 2000;20(3):795–817.

30. Macpherson, CN, Bartholomot, B, Frider, B. Application of ultrasound in diagnosis, treatment, epidemiology, public health and control of Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis. Parasitology. 2003;127(suppl):S21–S35.

31. Czermak, BV, Akhan, O, Hiemetzberger, R, et al. Echinococcosis of the liver. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(2):133–143.

32. Etlik, O, Bay, A, Arslan, H, et al. Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI findings of atypical hepatic Echinococcus alveolaris infestation. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35(5):546–549.

33. Voros, D, Katsarelias, D, Polymeneas, G, et al. Treatment of hydatid liver disease. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2007;8(6):621–627.

34. Ishikawa, Y, Sako, Y, Itoh, S, et al. Serological monitoring of progression of alveolar echinococcosis with multiorgan involvement by use of recombinant Em18. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3191–3196.

35. Fotedar, R, Stark, D, Beebe, N, et al. Laboratory diagnostic techniques for Entamoeba species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(3):511–532.

36. Kays, DW. Pediatric liver cysts and abscesses. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1992;1(2):107–114.

37. Krogstad, DJ, Spencer, HC, Jr., Healy, GR, et al. Amebiasis: epidemiologic studies in the United States, 1971-1974. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88(1):89–97.

38. Rao, S, Solaymani-Mohammadi, S, Petri, WA, Jr., et al. Hepatic amebiasis: a reminder of the complications. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(1):145–149.

39. Manzella, A, Ohtomo, K, Monzawa, S, et al. Schistosomiasis of the liver. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(2):144–150.

40. Chitsulo, L, Engels, D, Montresor, A, et al. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop. 2000;77(1):41–51.

41. Palmer, PE. Schistosomiasis. Semin Roentgenol. 1998;33(1):6–25.

42. Cesmeli, E, Vogelaers, D, Voet, D, et al. Ultrasound and CT changes of liver parenchyma in acute schistosomiasis. Br J Radiol. 1997;70(835):758–760.

43. Fabre, V, Wu, H, PondTor, S, et al. Tissue inhibitor of matrix-metalloprotease-1 predicts risk of hepatic fibrosis in human Schistosoma japonicum infection. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(5):707–714.