93 Infections of the Urinary Tract

Etiology and Pathogenesis

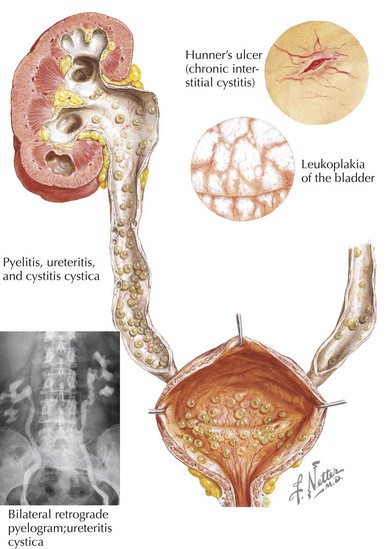

Infections of the urinary tract begin with ascension of flora that transiently colonize the lower urinary tract. The most common organism responsible for infection is the enteric gram-negative organism Escherichia coli. Other gram-negative organisms include Klebsiella, Proteus, Citrobacter, and Enterobacter spp. Gram-positive infections by enterococcus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and rarely Staphylococcus aureus are also known to occur. For infection to take place, the organisms must not only be present in the urinary tract but also needs to attach, adhere to, and invade the mucosa and epithelium. The bacteria are then able to ascend via the epithelial cells to the bladder and kidney (Figure 93-1). It is thought that genetically determined variation in the host’s defense against this process may explain the familial association of UTIs among first-degree relatives.

Clinical Presentation

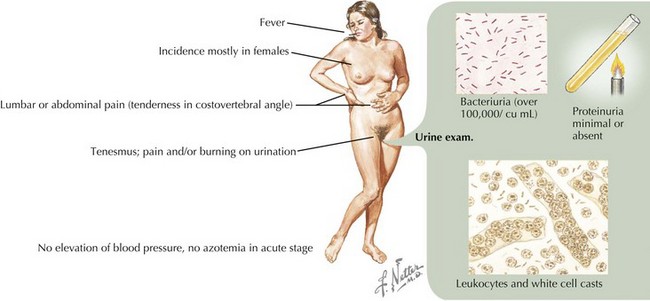

On physical examination of an infant or child with suspected UTI, it is important to note the degree of fever (if present) and any signs of cardiovascular instability that would reflect severe illness. Other findings on examination, more common in older patients, may include suprapubic or costovertebral tenderness. A complete abdominal examination should be performed to assess for any abdominal masses or abnormal distension of the bladder. A genital examination should look for any signs of urethritis or vulvovaginitis and for any anatomic abnormalities. If the patient is febrile, attention should also be paid to other potential sources of fever (Figure 93-2).

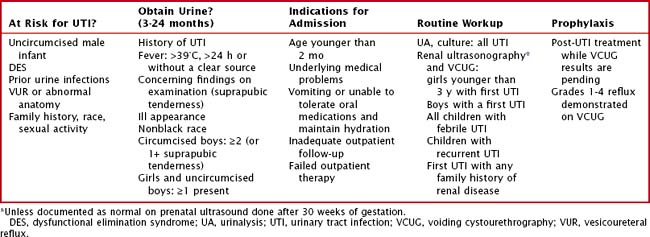

Evaluation and Management (Table 93-1)

Laboratory Evaluation

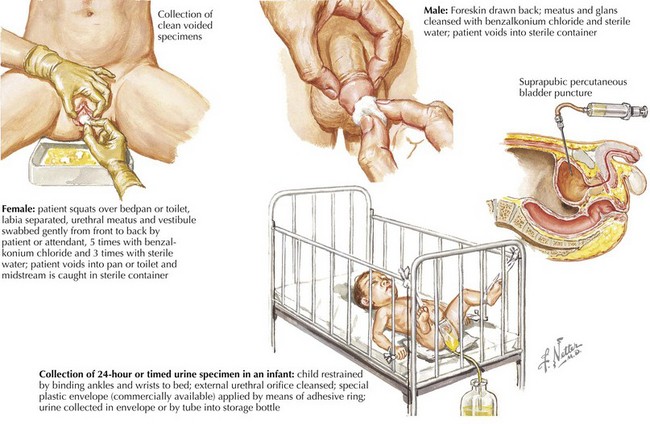

After it has been decided to obtain urine, the clinician must then determine how best to obtain it. For an infant, urine can be obtained by bag specimen, urethral catheterization, and suprapubic aspiration. The bag specimen is the most convenient but is of limited utility and generally not recommended because of the high probability of contamination from skin flora. It cannot be used for culture, and urinalysis is only useful if results are negative. Care must be taken, however, to analyze the sample promptly after voiding because the false results increase as the urine stagnates. Catheterized specimen is the primary means of obtaining urine in the infant for urine culture or enhanced urinalysis. Suprapubic aspiration can also be performed if catheterization is repeatedly unsuccessful or contraindicated, which despite its invasive nature is very well tolerated when performed correctly. For toilet-trained children, a clean catch is the primary means of collection for urinalysis and culture (Figure 93-3).

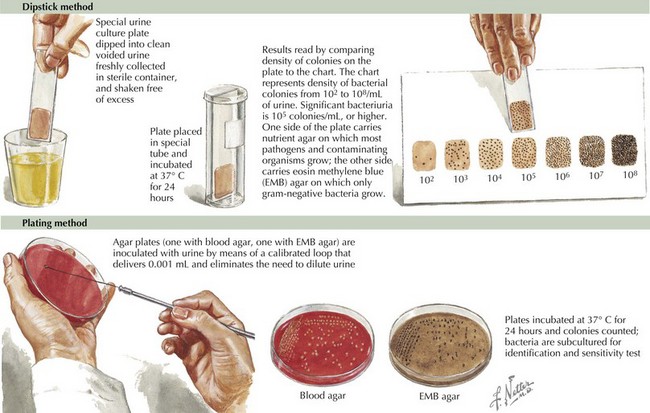

The gold standard for diagnosis is the urine culture, which not only makes the diagnosis but also helps to guide antimicrobial management. Growth criteria for definite infection are different depending on the means of collection, with any growth significant for a suprapubic aspirate and >50,000 or >100,000 colonies for a catheterization and clean catch, respectively. Although the current American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recognize 10,000 colonies from a catheterization specimen as significant, recent evidence suggests the 10,000 to 50,000 range be classified as indeterminate and a repeat specimen be obtained. When empiric coverage has already been initiated, however, this may not be practical, and the decision to treat will likely incorporate other factors (clinical presentation, positive or negative urinalysis). In the majority of cases, any growth of nonpathogens or mixed flora indicates contamination and the need for a new specimen (Figure 93-4).

Imaging

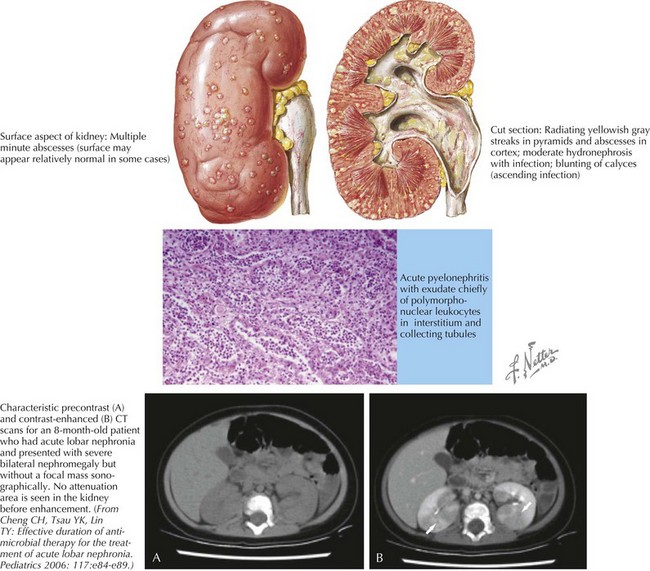

Three modalities of imaging are available to the clinician in the evaluation of UTIs: voiding cystourethrography (VCUG), renal ultrasound, and renal scintigraphy (DMSA [dimercaptosuccinic acid] scan). Intravenous pyelography (IVP) is rarely used in the pediatric population and is not discussed here. Overall, the goals of these studies are to identify any anatomic abnormalities that may predispose the patient to recurrent infections, evaluate for complications such as renal abscess or lobar nephronia (Figure 93-5), and look for evidence of renal scarring. VCUG, which involves catheterization and subsequent imaging of instilled dye during voiding, is an excellent test to evaluate for the presence and degree of VUR. Renal ultrasound can identify certain anatomic anomalies (e.g., ureteral dilatation, duplication), is noninvasive, and has the benefit of no radiation exposure. It is not able to identify renal scarring or VUR. Current recommendations are for these two studies to be performed in:

Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Hodson EM, Willis NS, Craig JC: Antibiotics for acute pyelonephritis in children, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD003772, 2007.

Keren R, Chan E. A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials comparing short- and long-course antibiotic therapy for urinary tract infections in children. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):E70-0.

Montini G, Zucchetta P, Tomasi L, et al. Value of imaging studies after a first febrile urinary tract infection in young children: data from Italian Renal Infection Study 1. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e239-e246.

Pennesi M, Travan L, Peratoner L, et al. Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1489-e1494.

Shaikh N, Morone NE, Lopez J, et al. Does this child have a urinary tract infection? JAMA. 2007;298(24):2895-2904.

Zaoutis B, Chiang W. Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.