47 Infections of the Thoracic Spine

KEY POINTS

Introduction

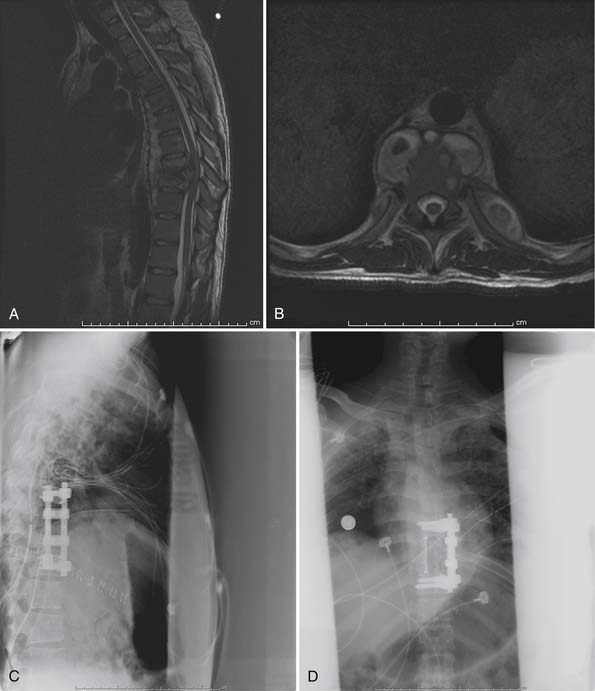

Spinal infections are also classified by the primary location of pathogenesis. Sole involvement of the disc space is referred to as discitis. Osteomyelitis is an infection of the bony spine (Figure 47-1). Osteodiscitis or spondylodiscitis is combined involvement of the intervertebral disc and the vertebra. Abscess or granulation formation can occur in a subdural, epidural, or paravertebral location (Figure 47-2). Frequently, spinal infections invade all compartments of the spinal column, including the soft tissues, bony spine, and within the spinal canal.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of spinal infection ultimately begins with the individual’s underlying predisposing risk factors. Advanced age, diabetes, and multiple medical comorbidities are associated with increased risk for spinal infection. Additionally, spinal surgery, intravenous drug use, and immunocompromise contribute to further risk. Infection generally metastasizes hematogenously to the spine from extraspinal sources such as the urinary tract, respiratory system, skin or soft tissue infections, or cardiac vegetations. Direct inoculation from surgery, percutaneous procedures, or penetrating trauma is an additional modality for bacterial seeding. Local invasion to the spine also occurs from infected adjacent or contiguous sources such as the retroperitoneal, abdominopelvic, pleural, or retropharyngeal spaces. Spread of infection can also occur within the spinal column by direct extension from the bony or soft tissue elements to the epidural space.

Bacterial Pathogenesis

Pathologic sequelae of spinal infection include loss of spinal alignment with progressive deformity, and risk of neurological compromise. Bacterial involvement of the spinal column with subsequent inflammatory infiltration causes bony destruction and eventually erodes the subchondral plate to involve the relatively avascular disc space (Figure 47-3). Advanced bone loss, particularly across multiple adjacent segments, combined with disc space narrowing, leads to progressive kyphotic deformity. neurological compromise may result from severe bony destruction, resulting in pathologic fracture with retropulsed bony fragments into the canal. Epidural abscess formation or extension of inflammatory granulation tissue into the canal can cause direct compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots. Additionally, septic thrombosis of veins within the epidural space or the arteriolar supply can cause ischemic injury. Particularly, in a spinal cord already compromised by mechanical compression from either an abscess or fracture, hypoperfusion from thrombosed feeding arteries or draining veins may lead to rapid neurological deterioration.

Gram-positive cocci are the most prevalent inciting organism, representing 50% to 67% of all causative organisms. Staphylococcus aureus is the most prevalent bacteria identified, accounting for 80% of all gram-positive infections, and 55% of all spinal infections. In a meta-analysis of 915 patients with epidural abscess, S. aureus was identified as the causative organism in 73.2% of cases. Gram-negative bacteria, particularly Escherichia coli and Proteus, are more frequently identified in patients with preexisting urinary tract infections. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is most common among immunocompromised patients or intravenous drug users. Indolent infections are more likely to occur with low-virulence organisms such as Streptococcus viridans or Staphylococcus epidermisdis.

Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis of the spine results from hematogenous spread of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from well-established extraspinal foci, primarily originating from the respiratory or genitourinary tract. Unlike pyogenic osteomyelitis, spinal tuberculosis may begin in the paradiscal area and spread under the anterior longitudinal ligament to involve adjacent vertebral bodies, while relatively preserving the disc space. Additionally, spinal tuberculosis frequently involves the posterior spinal arch, whereas pyogenic osteomyelitis is primarily a disease of only the anterior spinal column. Because spinal tuberculosis often causes widespread destruction of a spinal segment, vertebral collapse with pathologic subluxation, kyphosis, and retropulsion occur in severe cases and present greater risk for acute neurological compromise than bacterial osteomyelitis (Figure 47-4). Delayed chronic paresis also occurs with progressive deformity or in the setting of epidural granulomas that result from longstanding tuberculous infection.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Imaging

Plain spine x-rays may demonstrate characteristic findings associated with osteomyelitis or osteodiscitis, and often serve as a rapid method for surveying the full spinal axis for potential infection. Disc space narrowing is the earliest and most consistent radiographic finding, occurring in 74% of cases, generally after approximately 2 to 4 weeks. Enlargement of the paravertebral shadow may indirectly suggest a thoracic paravertebral abscess. After 3 to 6 weeks, leukocyte infiltration into the subchondral bone and vertebral body leads to bony destructive changes, appearing as a lytic area in the anterior aspect of the vertebral body adjacent to the disc, or blurring of the endplates. With advanced bone loss, the vertebral body collapses. Thirty-six inch standing x-rays are essential for assessing progression of sagittal and coronal plane deformity in severe cases. With chronic disease (after 8 to 12 weeks), reactive bone formation and endplate sclerosis occurs. Ultimately, the reparative process results in new bone formation and hypertrophic changes. Eventually, 50% of cases lead to spontaneous fusion; however, it may require several years for this to take place. The remaining cases likely form a fibrous ankylosis which may similarly effectively immobilize the involved segment.

Management

Surgical Management

Timing of surgical intervention is also a critical factor. Patients with acute neurologicalal deficits secondary to spinal cord compression require emergent decompression to prevent irreversible injury. Persistent sepsis despite medical therapy, with significant abscesses and infected or necrotic tissue, may necessitate urgent drainage or debridement to decrease the overall infectious burden and facilitate antimicrobial penetration. Acute instability that threatens neurological structures demands immediate immobilization and may require urgent operative stabilization. Delayed surgical intervention is indicated for patients that are stable neurologically and clinically, but have disabling pain or evidence of chronic progressive deformity. Generally, in these instances, surgical instrumented stabilization and arthrodesis is performed after the acute infection is cleared.

Posterior Approach

With the advent of pedicle screw-rod fixation, a single-stage posterior approach for decompression, debridement, and instrumented stabilization may be an appropriate alternative surgical modality (Figure 47-5 A-C). Various posterior approaches for accessing anterior thoracic and lumbar pathology are available. Costotransversectomy, lateral extracavitary, and transpedicular techniques allow access to the anterior spinal column via a posteriorly based approach. With these techniques, debridement of varying degrees of the anterior column may be performed, although complete vertebrectomy via a solely posterior approach is technically challenging, given limited visualization of the anterior aspect of the thecal sac.

After debridement of infected, necrotic tissue, anterior column reconstruction may be achieved using either stackable or expandable interbody devices that are designed to be inserted from a posterior approach (Figure 47-6 A-B). Particularly in the thoracic spine, a unilateral single nerve root may be ligated to facilitate insertion of an interbody cage. Again, however, limited exposure via a posterior approach may restrict the size of interbody graft that can be inserted, thereby presenting potential risk for graft subsidence, kyphosis, or nonunion. Supplemental posterior fixation with a pedicle screw-rod construct provides instrumented stabilization, and thereby prevents progressive sagittal deformity as well as facilitates arthrodesis. A single-stage posterior approach for debridement, decompression, and stabilization may be particularly suited for medically compromised patients with osteomyelitis who may not tolerate a thoracotomy for anterior exposure.

Anterior Approach

Anterior procedures to surgically treat osteomyelitis have become increasingly popular since Hodgson first reported anterior debridement and fusion for spinal tuberculosis in 1960, and have since become the standard treatment for pyogenic osteomyelitis as well. Because the pathology is generally ventral, an anterior approach allows for thorough debridement of infected and necrotic tissue, and drainage of psoas or paravertebral abscesses. With an anterior approach, it is possible to completely remove all necrotic tissue until bleeding, well-vascularized bone is encountered, and to decompress the ventral thecal sac. Anterior spinal column reconstruction with an interbody graft for arthrodesis, anterior column support, and restoration of sagittal alignment is also best attained from an anterior approach. Spinal fixation for stabilization and to facilitate arthrodesis can also be performed from an anterior approach (Figure 47-7 A-D).

Anterior Approach with Anterior Fixation

Dai et al reported on 22 patients treated with an anterior-only approach for the treatment of thoracic and lumbar osteomyelitis.1 Patients underwent an anterior debridement, interbody fusion with autologous graft, and anterior instrumented stabilization. Follow-up was for a minimum of 3 years, and there were no cases of residual or recurrent infection. ESR and CRP returned to normal levels within 4 to 10 weeks postoperatively.

Single-Stage Anterior and Posterior Procedure

Korovessis et al studied 24 patients with osteomyelitis treated with a single-stage anterior debridement, partial vertebrectomy, mesh cage and autologous bone graft, and supplemental pedicle screw fixation.2 Follow-up was for an average of 56 months, with all patients demonstrating complete resolution of infection. While three patients who were ASIA A on presentation remained ASIA A postoperatively, patients with incomplete spinal cord injuries improved an average of 1.4 Frankel grades postoperatively. Six patients with incomplete injuries preoperatively had full recovery of neurological function within 1 year of surgery. Eleven patients who were neurologicalally intact preoperatively returned to full premorbid functional and activity levels within 4 to 6 months after surgery. Visual analog pain scores improved postoperatively as well.

Two-Staged Anterior-Posterior Procedure

Circumferential treatment of vertebral osteomyelitis can be performed as a single-stage procedure or in a two-staged fashion, with initial anterior debridement and then delayed posterior fixation. Staged spinal surgery has gained popularity for the treatment of various other complex spinal disorders such as deformity, trauma, and oncologic and rheumatologic conditions. The benefit of staged surgery is a shorter operative time and less blood loss for each individual procedure, which may be particularly relevant for patients with worse overall general health. A two-staged surgery allows for a convalescent period to bridge between the two procedures, in which the patients may have an opportunity to recover clinically and neurologicalally. Also, performing supplemental posterior instrumentation in a delayed manner allows for a longer course of antimicrobial therapy to further reduce the infected environment prior to implantation of hardware.

Dimar et al reported on 42 patients with osteomyelitis treated with anterior debridement and strut grafting, followed by delayed instrumented posterior spinal fusion at an average of 14.4 days after the initial procedure.3 Many patients were acutely ill at presentation requiring urgent treatment, but were in poor overall clinical status to undergo an extensive circumferential operation. Most were significantly debilitated from inadequate nutrition as well. For these patients, Dimar et al performed anterior debridement and anterior strut grafting urgently to thoroughly remove the infection and restore anterior column support. Patients were then immobilized in an external orthosis, continued on intravenous antibiotics, aggressively resuscitated nutritionally, and initiated on physical therapy. Delayed posterior spinal fusion was then performed on a semi-elective basis when patients were clinically stable to undergo a second procedure.

Use of Instrumentation

Ruf et al examined 88 patients with vertebral osteomyelitis treated with anterior column reconstruction with a titanium mesh cage.4 Thirty-four cases involved placement of the cage in a single disc space. Twenty-eight cases replaced a single vertebral level. Twenty-three cases were two-level vertebral body replacements, and three cases involved three-level reconstructions. Kyphosis angles at the affected levels improved a mean 11.2° after surgery, with a minimal loss of correction of only 1.4°. Four patients with osteoporosis had evidence of cage settling, with three cases requiring revision surgery and additional posterior instrumentation. All patients demonstrated solid arthrodesis at last follow-up, with no recurrent infection.

Pee et al retrospectively reviewed 60 patients who underwent anterior debridement, posterior stabilization, and anterior column reconstruction with either tricortical iliac strut, titanium cage, or polyether ether ketone (PEEK) cage5. The titanium and PEEK cages were packed either with allograft bone chips, with autograft, or with mixed autograft/allograft for arthrodesis. Pee et al observed that the tricortical iliac strut group had an average 200 ml increase in operative blood loss compared to the titanium or PEEK cage groups. While there was no significant difference in postoperative fusion rate between iliac strut and cage groups, there was a significantly higher subsidence rate in the iliac strut group. Also, the mean time interval until subsidence was shorter in the autograft group compared to the cage group. They secondarily observed that patients with subsidence (regardless of graft type) had more pain and disability than those without subsidence. Therefore, the authors inferred that use of a cage may decrease the risk of this adverse outcome, although this was not proven to statistical significance in their series. Most relevant, however, was that all patients, regardless of iliac strut or cage, had normalization of ESR and CRP postoperatively, with complete resolution of infection at final follow-up.

Graft Type

A potentially exciting option is the use of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) to promote fusion. Recombinant human BMP (InFuse, Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA; OP-1, Stryker Biotech, Hopkinton, MA, USA) is a synthetic osteoinductive agent that has been demonstrated in both animal and clinical models to result in increased fusion rates. The use of BMP in the setting of spinal infection, however, has not been widely clinically explored and currently represents an off-label and contraindicated use of the product. Laboratory studies in animal models, however, show that BMP retains its osteoinductive properties even in the setting of acute or chronic infection. Interestingly, in experimental models, BMP in combination with antibiotics results in more rapid healing than BMP alone. This may be secondary to increased angiogenesis caused by BMP-stimulated osteoblast-derived vascular endothelial growth factor. Therefore increased vascular ingrowth not only facilitates osteogenesis, but also leads to increased local antibiotic delivery to better eliminate infection.

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Thoracoscopic Spinal Surgery

The literature reporting thoracoscopic treatment of vertebral osteomyelitis is limited. Muckely et al described three patients with thoracic osteomyelitis that underwent thoracoscopic partial corpectomy, anterior reconstruction, and anterior spinal fixation.6 The improvement in kyphotic angle among the three patients ranged from 6° to 15° with no evidence of loss of correction at a minimum of 22 months of follow-up. There were no cases of recurrence and no instances of graft or hardware failure. Of note, one patient in the series was ambulating as early as postoperative day one. Amini et al presented a case report of a 70-year-old patient who developed osteodiscitis after a T11-12 discectomy.7 The patient was treated with a thoracoscopic vertebrectomy, allograft strut, and anterior instrumentation. At 1-year follow-up, the patient demonstrated solid fusion without evidence of recurrent disease.

Percutaneous Technology

Recently, percutaneous technology has been developed to perform a variety of spinal procedures including discectomy, spinal decompression, interbody fusion, and instrumented stabilization. These minimally invasive techniques have been incorporated in the treatment of spinal infections as well. Nagata et al applied a technique for percutaneous excision of lumbar disc herniations as a method for aspiration and drainage of pyogenic spondylodiscitis.8 Under local anesthesia, a percutaneous trocar that is 5.4 mm in diameter is inserted under intraoperative fluoroscopy into the affected level. Through this trocar, specialized forceps and a motor-driven shaver are used to curette the infected disc and endplate, which are then removed piecemeal. After debridement, large volume irrigation is flushed through the trocar. Finally, a small suction drainage tube is left in the disc space and the trocar is removed to allow for postoperative continuous antibiotic suction-irrigation.

Nagata et al performed this procedure in 23 patients with spondylodiscitis.8 The causative organism was identified through cultured tissue removed during curettage in 53% of patients. Ninety-one percent of patients had immediate relief of back pain after surgery, with 43% ambulating without pain within 3 days of surgery. All patients were followed for a minimum of 2 years with only one patient requiring a repeat operation for recurrent infection. No vascular or neurological complications were encountered as a result of the procedure. Three of 6 patients with preoperative neurological deficits, however, continued to have mild sensory impairment at last follow-up, and therefore, this procedure is not recommended for patients with significant bony destruction, epidural abscess, or neurological compromise.

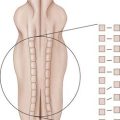

Instrumentation for spinal fixation of unstable pathologic fractures and deformity correction has also been advanced by percutaneous technology. Standard open placement of pedicle screws requires extensive dissection of the posterior musculature to expose the necessary anatomic landmarks for screw insertion and connecting rod placement. Cannulated pedicle screws, however, have been introduced that allow for placement of screws over a guidewire percutaneously inserted under fluoroscopic imaging. With this technique, multilevel fixation can be performed with multiple separate stab incisions for each screw placement (Figure 47-8 A-E). Novel technology has been developed to allow for introducing a connecting rod through the screw heads via an additional separate stab incision. Due to its low operative morbidity, percutaneous stabilization may have a particularly beneficial role as supplemental posterior fixation for patients undergoing primary anterior debridement and spinal reconstruction.

Prognosis

The prognosis for neurological recovery generally depends on the duration and severity of neurological impairment prior to intervention. Patients with epidural abscesses that are treated within 24 hours of onset of deficits have a better prognosis for recovery of function. Rigamonti et al observed that only 10% of patients with severe neurological deficits who were treated within 24 hours of onset of symptoms had poor neurologic outcomes, compared to 47% of patients treated more than 24 hours after onset of symptoms having a poor neurological outcome.9 Additionally, patients with complete paralysis, especially if present for more than 36 hours, do not generally recover, despite any intervention.

Chronic pain is a potential long-term complication associated with osteomyelitis, and may be multifactorial. Some studies have found that patients that underwent surgical intervention are actually less likely to have chronic back pain than those treated with antibiotics alone. Better restoration of sagittal alignment and spinal stabilization with surgery may account for this difference in outcome. However, 36% of patients treated only with medical therapy do recover without any long-term disabling back pain. This observation may be due to less severe bony destruction in patients treated nonsurgically, or to spontaneous fusion that occurs from the inflammatory response. Spontaneous bony ankylosis forms in 35% of patients; this, however, may require 6 to 24 months to occur. Deformity is another potential complication that may contribute to pain and long-term dysfunction. Deformity is more common with spinal tuberculosis, especially when occurring at the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine, or when involving more than 50% of one or more vertebral bodies. Good clinical outcomes, however, are demonstrated with surgical intervention. With an anterior decompression and fusion, 94% of patients with spinal tuberculosis recover normal neurological function, with a fusion rate of 92% at 5 years.

Conclusion

Spinal infections represent a wide-ranging spectrum of pathologic involvement and therefore are not amenable to simple treatment algorithms or protocols. General principles dictate that early diagnosis with identification of the pathogenic organism is critical for successful medical therapy with eradication of infection and minimized complications. Patients who are neurologicalally intact and clinically stable can generally be managed nonsurgically. Patients who present with neurological deficits, clinical deterioration despite medical therapy, or evidence of spinal instability, deformity, or chronic pain may necessitate surgical intervention. Currently, a variety of surgical treatment options are available ranging from minimally-invasive techniques to radical debridement with complex spinal reconstruction and instrumented stabilization.

1. Dai L.Y., Chen W.H., Jiang L.S. Anterior instrumentation for the treatment of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis of thoracic and lumbar spine. Eur. Spine J.. 2008;17(8):1027-1034.

2. Korovessis P., Repantis T., Iliopoulos P., Hadjipavlou A. Beneficial influence of titanium mesh cage on infection healing and spinal reconstruction in hematogenous septic spondylitis: a retrospective analysis of surgical outcome of twenty-five consecutive cases and review of literature. Spine. 2008;33(21):E759-E767.

3. Dimar J.R., Carreon L.Y., Glassman S.D., Campbell M.J., Hartman M.J., Johnson J.R. Treatment of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis with anterior debridement and fusion followed by delayed posterior spinal fusion. Spine. 2004;29(3):326-332. discussion 32

4. Ruf M., Stoltze D., Merk H.R., Ames M., Harms J. Treatment of vertebral osteomyelitis by radical debridement and stabilization using titanium mesh cages. Spine. 2007;32(9):E275-E280.

5. Pee Y.H., Park J.D., Choi Y.G., Lee S.H. Anterior debridement and fusion followed by posterior pedicle screw fixation in pyogenic spondylodiscitis: autologous iliac bone strut versus cage. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2008;8(5):405-412.

6. Muckley T., Schutz T., Schmidt M.H., Potulski M., Buhren V., Beisse R. The role of thoracoscopic spinal surgery in the management of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. Spine. 2004;29(11):E227-E233.

7. Amini A., Beisse R., Schmidt M.H. Thoracoscopic debridement and stabilization of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech.. 2007;17(4):354-357.

8. Nagata K., Ohashi T., Ariyoshi M., Sonoda K., Imoto H., Inoue A. Percutaneous suction aspiration and drainage for pyogenic spondylitis. Spine. 1998;23(14):1600-1606.

9. Rigamonti D., Liem L., Sampath P., et al. Spinal epidural abscess: contemporary trends in etiology, evaluation, and management. Surg. Neurol.. 1999;52(2):189-196. discussion 97