Infections of the Reproductive System

After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

• Identify the organs and structures of the female and male reproductive systems

• Discuss the differences and similarities between the female and male reproductive systems regarding structure and function

• Describe the common microbial infections that affect the female reproductive system

• Describe the common microbial infections that affect the male reproductive system

• Discuss the structural and functional interactions between the urinary and reproductive systems and how they contribute to microbial infections

• List the common symptoms of both female and male reproductive system infections

• Identify the common methods for the diagnosis of reproductive system infections

• Discuss preventive measures that can be taken to minimize reproductive system infections

• Identify reproductive system infections that can also be sexually transmitted

• Discuss the different methods of treatment for reproductive system infections

Introduction

The human reproductive system consists of numerous organs and structures that are often closely associated with the urinary system (see Chapter 15, Infections of the Urinary System). Many texts will combine the two systems into the urogenital system. Although different in purpose and function these systems sometimes share the same organs/structures and therefore are susceptible to infections with the same microorganisms. This chapter specifically examines infections of the reproductive systems that are not sexually transmitted, as sexually transmitted infections are addressed in Chapter 17 (Sexually Transmitted Infections/Diseases).

• Competition from the normal resident flora

• Chemical conditions such as acidic pH

• Sphincter muscles in the ducts that prevent any backflow

• The flow of urine through parts of the system that wash away bacteria

• Enzymes such as lysozyme, found in semen and cervical mucus

Types of Infections

These infections impact the health and reproductive capacity of women, men, their families, and their communities. Consequences of the infections include infertility, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain, pelvic inflammatory disease, miscarriage, and increased risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections (see Chapter 17, Sexually Transmitted Infections/Diseases). Reproductive tract infections (RTIs) can be categorized as endogenous, iatrogenic, and sexually transmitted infections.

• Endogenous infections are common RTIs worldwide. These infections result from an overgrowth of the normal vaginal flora. They include bacterial vaginosis and candidiasis, both of which can be treated and cured.

• Iatrogenic infections are caused by the introduction of microorganisms into the reproductive tract through a medical procedure. These include the following: abortion, menstrual regulation, insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD), unhygienic conditions during childbirth, as well as sterilization procedures and circumcision performed under unhygienic conditions.

• Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are transmitted by sexual activity with an infected partner. STIs are discussed in Chapter 17.

Infections of the Female Reproductive System

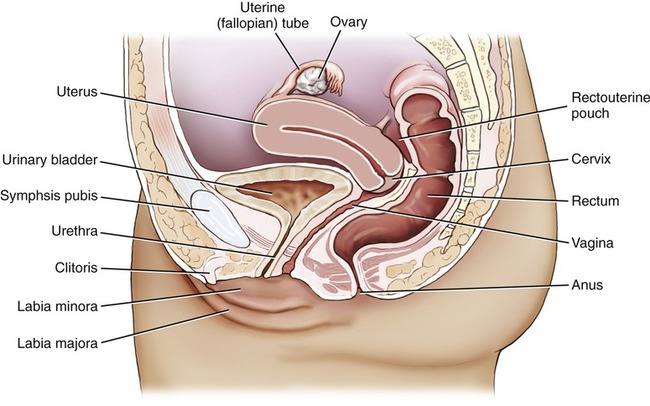

Because of the differences in structure, function, and systemic biochemical processes between males and females, the mechanisms of infection along with the targets and causative agents of infections differ considerably. The female reproductive system consists of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, and the external genitalia (Figure 16.1). The mammary glands are part of the female system but they are not necessary for reproduction; they play a role only after birth.

Bacterial Infections

Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS)

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is usually considered a blood-borne infection and is discussed in detail in Chapter 14 (Infections of the Circulatory System). However, one of the areas of the body especially prone to an infection causing TSS in women is the reproductive tract, specifically the vagina. The bacteria most often associated with TSS originating in the vagina is Staphylococcus aureus, and between 5% and 15% of women normally have S. aureus among their vaginal microflora. This type of infection normally manifests itself when use of a tampon causes a lesion in the vagina. The menstrual flow blood accumulates in the absorbent material of the tampon, which provides ideal growing conditions for the bacteria. As the bacteria multiply they produce exotoxin C, which can travel into the bloodstream through the lesion in the tissue of the vagina, causing a systemic reaction. Manifestations of TSS include the following:

Protozoan Infections

Protozoans are eukaryotic organisms (see Protozoans in Chapter 8, Eukaryotic Microorganisms), some of which can be parasites of humans. The organism may colonize and infect the oropharynx, duodenum, colon, and urogenital tract of humans.

Trichomoniasis

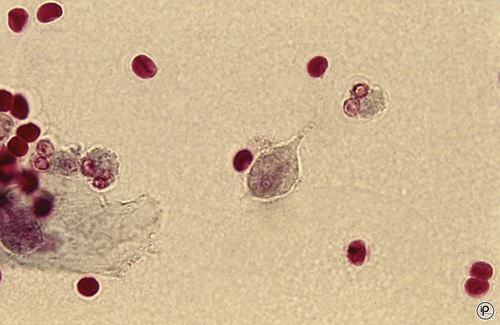

Trichomoniasis is transmitted primarily through sexual intercourse; however, there have been cases of transfer by other means. Although a relatively rare occurrence, there are confirmed cases of children becoming infected due to contact with contaminated linens and toilet seats. The organism that causes the infection is Trichomonas vaginalis (Figure 16.2), a large flagellate with an undulating membrane. The organism is thought to be part of the normal microflora, where it feeds on bacteria and cell secretions. The optimal pH for growth of this organism is 5.5 to 6.0, and so it is only when the pH of vaginal secretions is disturbed that conditions favor the growth of this protozoan. Successful competition with the normal flora will result in the overgrowth of Trichomonas to an infectious level. Other conditions such as bacterial antibiotic therapy, diabetes, and physical lesions may also favor an infection with this protozoan. Symptoms of infection include the following:

HEALTHCARE APPLICATION

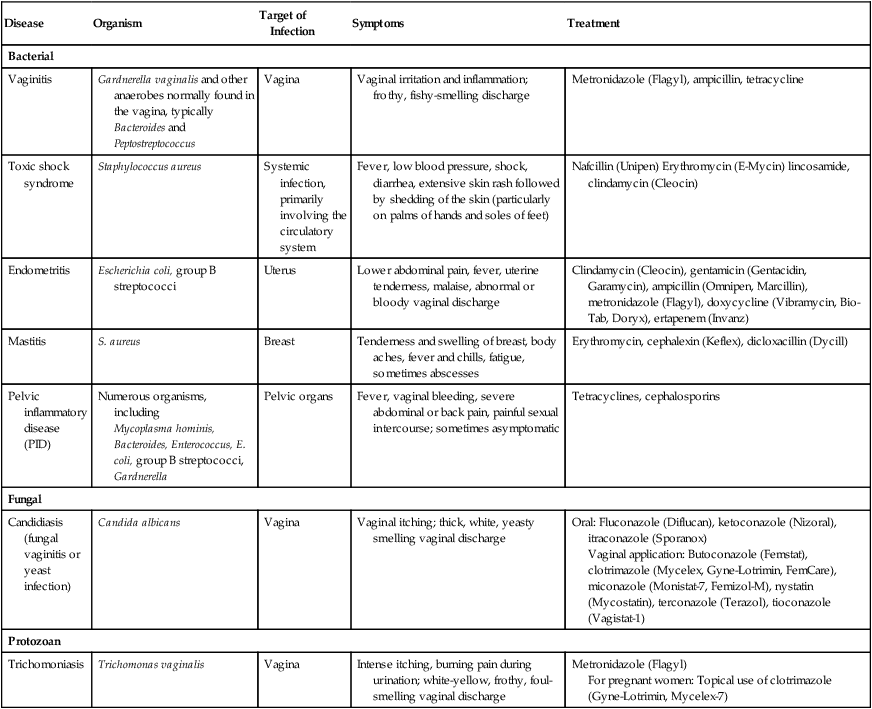

Nonsexually Transmitted Diseases of the Female Reproductive System

| Disease | Organism | Target of Infection | Symptoms | Treatment |

| Bacterial | ||||

| Vaginitis | Gardnerella vaginalis and other anaerobes normally found in the vagina, typically Bacteroides and Peptostreptococcus | Vagina | Vaginal irritation and inflammation; frothy, fishy-smelling discharge | Metronidazole (Flagyl), ampicillin, tetracycline |

| Toxic shock syndrome | Staphylococcus aureus | Systemic infection, primarily involving the circulatory system | Fever, low blood pressure, shock, diarrhea, extensive skin rash followed by shedding of the skin (particularly on palms of hands and soles of feet) | Nafcillin (Unipen) Erythromycin (E-Mycin) lincosamide, clindamycin (Cleocin) |

| Endometritis | Escherichia coli, group B streptococci | Uterus | Lower abdominal pain, fever, uterine tenderness, malaise, abnormal or bloody vaginal discharge | Clindamycin (Cleocin), gentamicin (Gentacidin, Garamycin), ampicillin (Omnipen, Marcillin), metronidazole (Flagyl), doxycycline (Vibramycin, Bio-Tab, Doryx), ertapenem (Invanz) |

| Mastitis | S. aureus | Breast | Tenderness and swelling of breast, body aches, fever and chills, fatigue, sometimes abscesses | Erythromycin, cephalexin (Keflex), dicloxacillin (Dycill) |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) | Numerous organisms, including Mycoplasma hominis, Bacteroides, Enterococcus, E. coli, group B streptococci, Gardnerella |

Pelvic organs | Fever, vaginal bleeding, severe abdominal or back pain, painful sexual intercourse; sometimes asymptomatic | Tetracyclines, cephalosporins |

| Fungal | ||||

| Candidiasis (fungal vaginitis or yeast infection) | Candida albicans | Vagina | Vaginal itching; thick, white, yeasty smelling vaginal discharge | Oral: Fluconazole (Diflucan), ketoconazole (Nizoral), itraconazole (Sporanox) Vaginal application: Butoconazole (Femstat), clotrimazole (Mycelex, Gyne-Lotrimin, FemCare), miconazole (Monistat-7, Femizol-M), nystatin (Mycostatin), terconazole (Terazol), tioconazole (Vagistat-1) |

| Protozoan | ||||

| Trichomoniasis | Trichomonas vaginalis | Vagina | Intense itching, burning pain during urination; white-yellow, frothy, foul-smelling vaginal discharge | Metronidazole (Flagyl) For pregnant women: Topical use of clotrimazole (Gyne-Lotrimin, Mycelex-7) |

Infections of the Male Reproductive System

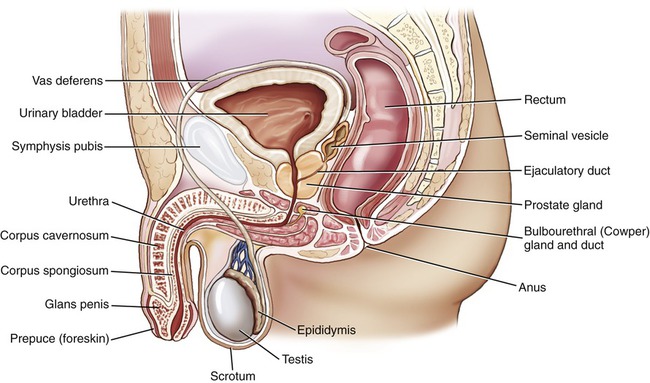

The male reproductive system consists of the testes, a system of ducts, the accessory glands (prostate, seminal vesicles, and Cowper’s gland), and the penis (Figure 16.3). Differences in structure and function between the female and male reproductive systems result in different types of infections. In general, the male reproductive system is sterile and has no population of normal flora.

Protozoan Infections

Trichomoniasis

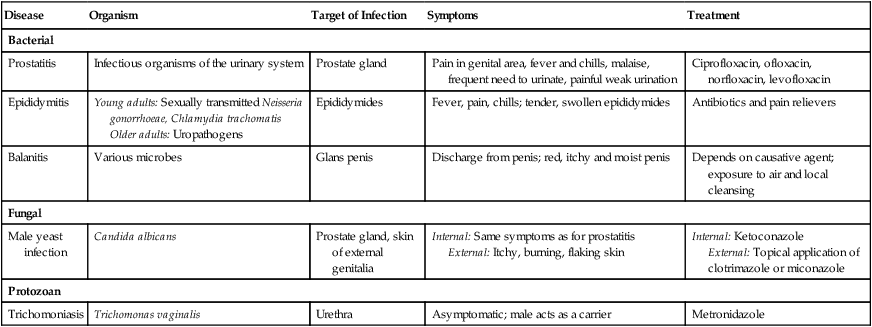

HEALTHCARE APPLICATION

Nonsexually Transmitted Diseases of the Male Reproductive System

| Disease | Organism | Target of Infection | Symptoms | Treatment |

| Bacterial | ||||

| Prostatitis | Infectious organisms of the urinary system | Prostate gland | Pain in genital area, fever and chills, malaise, frequent need to urinate, painful weak urination | Ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, norfloxacin, levofloxacin |

| Epididymitis | Young adults: Sexually transmitted Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis Older adults: Uropathogens |

Epididymides | Fever, pain, chills; tender, swollen epididymides | Antibiotics and pain relievers |

| Balanitis | Various microbes | Glans penis | Discharge from penis; red, itchy and moist penis | Depends on causative agent; exposure to air and local cleansing |

| Fungal | ||||

| Male yeast infection | Candida albicans | Prostate gland, skin of external genitalia | Internal: Same symptoms as for prostatitis External: Itchy, burning, flaking skin |

Internal: Ketoconazole External: Topical application of clotrimazole or miconazole |

| Protozoan | ||||

| Trichomoniasis | Trichomonas vaginalis | Urethra | Asymptomatic; male acts as a carrier | Metronidazole |

Summary

• The primary organs/structures of the female reproductive system include the following: ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, and vagina (mammary glands can also be included).

• The primary organs/structures of the male reproductive system include the following: testes, prostate gland, urethra, penis, and associated ducts.

• Because of close physical proximity and the sharing of some ducts, infections of the urinary tract often contribute to infections of the reproductive system, particularly in the male system, where infection almost always occurs when infected urine backs up into the urethra.

• Urinary tract infections (UTIs) may be endogenous, iatrogenic, or sexually transmitted (see Chapter 17, Sexually Transmitted Infections/Diseases).

• Common bacterial infections of the female reproductive system that are not strictly sexually transmitted include vaginitis, toxic shock syndrome, endometritis, mastitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.

• Group B streptococci (S. agalactiae) can colonize in the vagina, not causing an infection in the woman, but possibly being transmitted to a newborn, often with devastating results.

• Fungal infections of the female reproductive system are limited to candidiasis; and protozoan infections are limited to trichomoniasis.

• Preventive measures that can be taken to minimize the potential for vaginitis include avoiding the following: frequent douching, tampons that irritate the vagina, tight pants, and use of panties/panty hose without cotton crotch material.

• Common microbial infections of the male reproductive system include bacterial prostatitis, epididymitis, balanitis, male yeast infection, and trichomoniasis (protozoan).

• The methods most commonly used to diagnose a reproductive system infection are the microscopic examination of discharge from infected organs and microscopic examination of urine for infection organisms.

Review Questions

1. The female reproductive system includes the following organs/structures:

a. Ovaries, kidneys, uterus, vagina

b. Uterus, vagina, bladder, duodenum

2. Bacterial infections of the female reproductive system include:

a. Vaginitis, toxic shock syndrome, endometritis, salpingitis

b. Nephritis, endometritis, vaginitis, pelvic inflammation disease

3. Bacteria that have been identified as frequently responsible for nonsexually transmitted infections of the reproductive system include:

a. Escherichia coli, Gardnerella vaginalis, Staphylococcus aureus

b. Streptococcus faecalis, Klebsiella oxytoca, Serratia marcescens

c. Clostridium tetani, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus

d. Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Helicobacter pylori, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

4. The most common bacterial nonsexually transmitted infection of the male reproductive system is:

5. The normal flora present in the healthy male reproductive system is best characterized as:

6. Methods typically used to diagnose bacterial infections of the reproductive system include:

a. Microscopic examination of discharge from infected organ and microscopic examination of urine for organisms

b. Biopsy of infected tissue and use of selective media

c. Microscopic examination of fecal sample and protein test of urine

7. Factors that can increase the chances of vaginitis are:

a. Urinary blockage, drug use, stress

b. Use of antibiotics, pregnancy, menopause

8. The organism that is responsible for the vast majority of cases of fungal vaginitis is:

9. Symptoms of prostatitis include:

a. Muscle aches, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes

b. Painful joints, nausea, painful urination

10. Measures that can be taken to prevent bacterial vaginitis include:

a. Douching, use of contraceptive pills, exercise

b. Use of absorbent tampons, frequent douching, avoidance of tight pants

c. Avoidance of douching, wearing panties with cotton crotch, exercise

d. Avoidance of tight pants, wearing panties with cotton crotch, infrequent douching

11. Vaginal epithelial cells that can be examined to determine the presence of Gardnerella vaginalis are referred to as __________ __________.

12. Enzymes such as __________, found in cervical mucus and semen, are instrumental in providing a chemical defense against bacterial infections of the reproductive organs.

13. The bacterium most frequently responsible for toxic shock syndrome that originates in the reproductive system is __________.

14. Although normally caused by sexually transmitted organisms, pelvic inflammatory disease is sometimes caused by __________, which is a common part of the vaginal microflora.

15. __________ is a collective term for any extensive bacterial infection of the pelvic organs.

16. Identify measures that can be taken to prevent the recurrence of toxic shock syndrome originating in the reproductive organs.

17. List some members of the normal microflora of the reproductive system and discuss the effect they have on bacterial infections of the reproductive system.

18. As women age, discuss the role of changing pH within organs of the reproductive system and how this affects the potential for bacterial infections.

19. Discuss the features of the healthy reproductive system that contribute to the defense of the reproductive system from infections.

20. Discuss factors that may contribute to an abnormal increase in the normal microflora in female organs that could lead to vaginitis.