30 Infections of the Cervical Spine

KEY POINTS

Basic Science

There are several potential routes for the dissemination of infections to the cervical spine, including direct extension from contiguous structures, open spinal trauma or surgery, hematogenous, or lymphatic. Both venous and arterial mechanisms have been implicated in hematogenous spread. The Batson venous plexus was proposed as a valveless conduit through which infections of the pelvis, such as urinary tract infections, may spread to the spine. This venous mechanism has been largely refuted, and an alternative arterial route postulated.1 In the case of vertebral pyogenic osteomyelitis, infection is thought to seed the metaphyseal (subchondral) bone near to the anterior longitudinal ligament via a rich arterial network. The posterior spinal arteries that branch off the dorsal artery entering the intervertebral foramen are probably responsible for cervical epidural abscesses. Infections of the retropharyngeal space can enter the lymphatics and spread along the spinal nerves to communicate with the spinal subarachnoid space and Virchow-Robin space, thus leading to cervical subdural empyemas or cervical intramedullary abscesses.

Interestingly, discitis is seen in two distinct patient populations: pediatric and adult. While discitis in the pediatric population is usually caused by a hematogenous source, adult discitis occurs in patients who have undergone prior surgery involving the disc space. The reason for this clear distinction is that, as the spine ages, there are changes that take place in its vascularity. Histologic studies have shown that an end-arteriolar supply of the disc is present during infancy and childhood, and these end arteries are obliterated by the third decade of life.2

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Clinical Presentation

The most common chief complaint for all cervical spine infections is vague, nonspecific neck pain of a progressive nature. With pyogenic osteomyelitis and discitis, this pain is exacerbated by neck motion, and eventually becomes extremely debilitating. Radicular pain is frequently present in epidural abscesses, and results from either direct nerve root compression or inflammation.3 If a cervical epidural abscess spreads to the retropharyngeal space, then dysphagia or even airway compromise may result.

The time course to presentation for cervical spine infections varies from acute (less than 1 week), to subacute (1 to 6 weeks), to chronic (more than 6 weeks). In the case of pediatric discitis, this pain is usually so severe at an early stage that a diagnosis is made before the infection spreads to the adjacent vertebral bodies.4 For pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis, the presentation tends to be subacute to chronic in 90% of cases, partly because of its more insidious onset. A definitive diagnosis of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis is made, on average, 8 weeks to 3 months after disease onset.5 Patients who present acutely (less than 1 week) are more likely to be febrile, and to have other constitutional signs and symptoms.

Infections that result in the formation of a mass-occupying abscess have a greater chance of presenting with neurological deficit. This may be seen in vertebral osteomyelitis that extends into the epidural space, or with a primary spinal epidural abscess. Likewise, subdural empyemas and intramedullary abscesses cause neurological deficit at an early stage. In some instances of vertebral osteomyelitis, the bony quality is compromised to the extent that bony collapse may occur, leading to spinal instability and secondary neurological deficit. Sometimes, spinal epidural abscesses and subdural empyemas may cause neurological compromise that is out of proportion with the degree of compression. This is thought to be secondary to vascular compromise from venous compression, thrombosis, or thrombophlebitis.6

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

Much like the physical exam findings, laboratory data for cervical spinal infections can be rather obscure. The peripheral white blood cell count is usually normal or just slightly elevated. For this reason, it is imperative to check the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) when cervical infection is under consideration. In the case of pyogenic osteomyelitis, the ESR may be elevated to 43 to 87 mm/hr (Westergren method).7 Apart from its diagnostic value, the ESR is an important marker to assess the degree of response to treatment.

The next important diagnostic step is appropriate imaging of the spine. This investigation should begin with plain x-rays. In the case of discitis or vertebral osteomyelitis, narrowing of the disc space may be seen as early as 2 to 3 weeks after infection onset. By 10 to 12 weeks, there is sclerosis of the adjacent vertebral body endplates, due to the bony deposition caused by inflammation. This is likely related to the fact that the subchondral bone is highly vascular and, therefore, is the initial nidus of infection in the vertebral body.8 With time, the sclerotic process gives way to lysis of the bone, and thus blurring of the endplates on x-ray. The infection eventually spreads to involve the remainder of the vertebral body. In approximately 5% of pyogenic spinal infections, the infection involves the dorsal elements. As the bone is progressively compromised, bony collapse can take place and lead to fracture and deformity of the spine. Plain x-rays are usually normal with spinal epidural abscesses, subdural empyemas, and intramedullary abscesses.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains key to the diagnosis of cervical infections. For pyogenic osteomyelitis, the sensitivity and specificity rates of MRI are 96% and 93%, respectively.9 MRI allows the spinal cord, nerve roots, and paraspinal soft tissue to be visualized to determine the extent of their involvement by the infection. Pyogenic osteomyelitis, discitis, epidural abscesses, subdural empyemas, and intramedullary abscesses all usually appear hypointense on T1-weighted MRI, and hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI. T1-weighted MRI with contrast enhancement is also useful to delineate the margins of an abscess. Another important feature of infections that is clearly demonstrated by MRI is their tendency to span from one vertebral body to the other, through the intervening disc space. Tumors, on the other hand, usually involve the anterior vertebral bodies and skip the disc spaces.

Treatment

Posterior cervical laminectomy is used to treat cervical subdural empyemas and intramedullary abscesses. After durotomy, debridement or drainage of suppurative material is performed for subdural empyemas. For intramedullary abscesses, intraoperative ultrasound may be useful to localize the abscess. A midline myelotomy is then performed to access the abscess cavity. One must bear in mind that posterior cervical laminectomy has the potential to cause subsequent kyphotic deformity, especially in cases where the infection has also eroded the vertebral bodies anteriorly.

Clinical Case Example

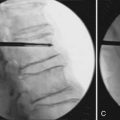

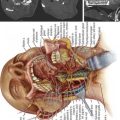

DISCITIS/SPINAL EPIDURAL ABSCESS

A 49-year-old male heroin abuser presented to the emergency department with progressive neck pain for 2 to 3 months, and inability to ambulate for the past 12 hours. His ESR was elevated, prompting imaging of the neck with plain x-rays (Figure 30-1A) followed by MRI (Figure 30-1B). A diagnosis of cervical discitis with an associated ventral epidural abscess was made, for which he underwent emergent anterior cervical decompression and drainage of the spinal epidural abscess. His kyphotic deformity corrected with extension of the neck on the operating table, and anterior reconstruction was achieved with allograft and anterior cervical plating (Figure 30-1C). Over the next several weeks, the patient gradually regained strength in his lower extremities and walked into his follow-up clinic visit at 6 weeks.

When spinal instability is present, it is necessary to consider internal fixation, with or without arthrodesis. Gross purulence was once considered an absolute contraindication to bone graft and instrumentation because of concern about recurrent infection. However, there are few practical solutions for an unstable cervical spine. Fortunately, there is now an increasing body of evidence that instrumentation and fusion may be safely performed after all grossly infected material is removed.10

1. Wiley A.M., Trueta J. The vascular anatomy of the spine and its relationship to pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br.. 1959;41:796-809.

2. Conventry M.B., Ghormley R.K., Kernohan J.W. The intervertebral disc, its microscopic anatomy and pathology: part I: anatomy, development and physiology. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1945;27:105-112.

3. Martin R.J., Yuan H.A. Neurosurgical care of spinal epidural, subdural, and intramedullary abscesses and arachnoiditis. Orthop. Clin. North Am.. 1996;27:125-136.

4. Kemp H.B., Jackson J.W., Jeremiah J.D., Hall A.J. Pyogenic infections occurring primarily in intervertebral discs. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br.. 1973;55:698-714.

5. Vincent K.A., Benson D.R., Voegeli T.L. Factors in the diagnosis of adult pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. Orthop. Trans.. 1988;12:523-524.

6. Russell N.A., Vaughan R., Morley T.P. Spinal epidural infection. Can. J. Neurol. Sci.. 1979;6:325-328.

7. Ross P.M., Fleming J.L. Vertebral body osteomyelitis. Clin. Orthop.. 1976;118:190-198.

8. Allen E.H., Cosgrove D., Millard F.J. The radiological changes in infection of the spine and their diagnostic value. Clin. Radiol.. 1978;29:31-40.

9. Modic M.T., Feiglin D.H., Piraino D.W., Boumphrey F., et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: assessment using MRI. Radiology. 1985;157:157-166.

10. Fang D., Cheung K.M., Dos Remedios I.D., et al. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: treatment by anterior spinal debridement and fusion. J. Spinal Disorder. 1994;7:173-180.