92 Infections of the Central Nervous System

Meningitis and Meningoencephalitis

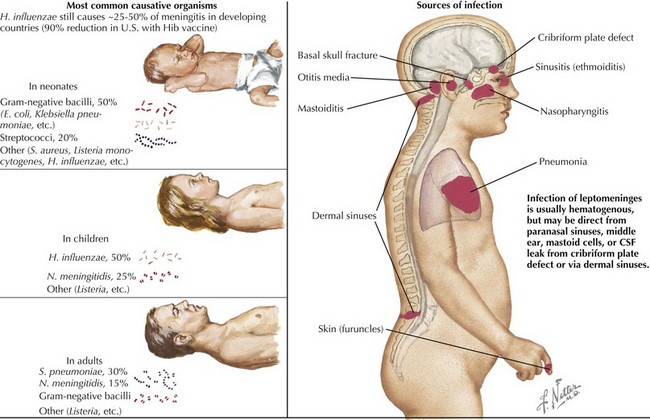

Etiology, Epidemiology, and Pathogenesis

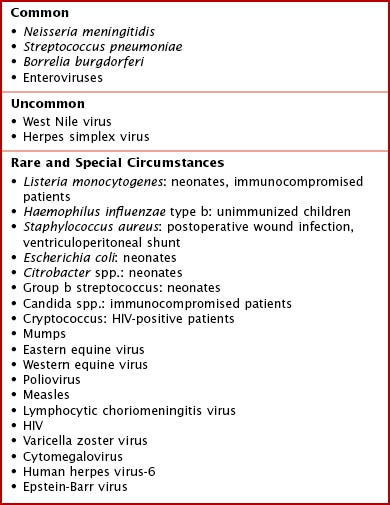

Because enteroviruses are the most common cause of viral meningitis and meningoencephalitis, the incidence of these infections peaks in the summer and fall and wanes in the winter. Herpes family viruses such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster (VZV) also cause meningoencephalitis, as can a number of other pathogens (Box 92-1).

In addition to hematogenous seeding of the CSF, bacteria can also gain access to the CNS via direct extension. Congenital malformations, such as dermoid sinuses, or traumatic injuries, including basilar skull fractures and penetrating trauma, can allow bacteria to enter the CSF. Infections of the sinuses, mastoid air cells, or middle ear can also act as portals of entry (Figure 92-1).

Clinical Presentation

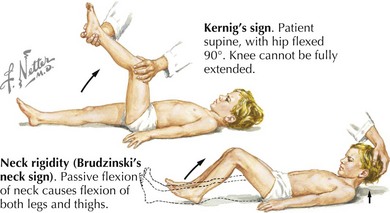

Neonates and infants with meningitis often present with nonspecific signs and symptoms. The most common parental complaint is fever, and the infants frequently have a history of irritability and poor feeding. They may also develop vomiting and a bulging fontanelle. In more severe cases, infants may present with lethargy or after having a seizure and may have focal neurologic deficits on examination. Although children with meningitis can present in many ways, toddlers and school-aged children are more likely to present with the “classic” signs and symptoms. These include high fever, photophobia, headache, neck stiffness, and vomiting. Of these, fever and headache are the most common. On physical examination, these patients may have nuchal rigidity as well as Kernig’s or Brudzinski’s signs (Figure 92-2). Children with disseminated N. meningitidis infections can have a petechial or purpuric rash. Infants with enteroviral meningitis often have an erythematous, macular rash. Cranial nerve palsies, especially of cranial nerve 7, and papilledema are frequently found in patients with Lyme meningitis but are unusual in other forms of meningitis.

Diagnostic Approach

The most important diagnostic procedure in the evaluation of a child with suspected bacterial meningitis is a lumbar puncture (LP; see Figure 92-1). An opening pressure should be measured at the time of the LP, and fluid should be sent for at least cell count with differential, gram stain and culture, protein, and glucose. If viral meningitis or meningoencephalitis is suspected, polymerase chain reaction tests for enteroviruses and HSV are useful. Viral culture is an additional way to make the diagnosis of viral meningitis, although many laboratories no longer perform this test. Various CNS infections have typical CSF parameters that can aid the clinician while the results of the CSF culture are pending (Table 92-1). If there is concern for elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) before performing the LP based on clinical signs such as papilledema or focal neurologic findings, it is reasonable to perform either a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study. These studies allow the clinician to determine whether there is a space-occupying lesion, such as a brain abscess or brain tumor, or dilatation of the ventricles. These findings indicate that there is a risk of brain herniation if a lumbar puncture were performed.

Focal Suppurative Infections: Brain Abscess

Brain abscesses are focal infections of the cerebrum or cerebellum.

Etiology, Epidemiology, and Pathogenesis

Older children are at risk for brain abscesses from direct extension of other infections, specifically sinusitis or otitis media with mastoiditis. Brain abscesses that arise secondary to these infections are often polymicrobial and may include both aerobic and anaerobic organisms. The most commonly isolated organism from these infections is Streptococcus intermedius, which is part of the Streptococcus milleri group. Other commonly isolated organisms include Streptococcus viridans and Staphylococcus aureus. Many additional pathogens have been reported as causative agents of brain abscesses (Box 92-2).

Diagnostic Approach

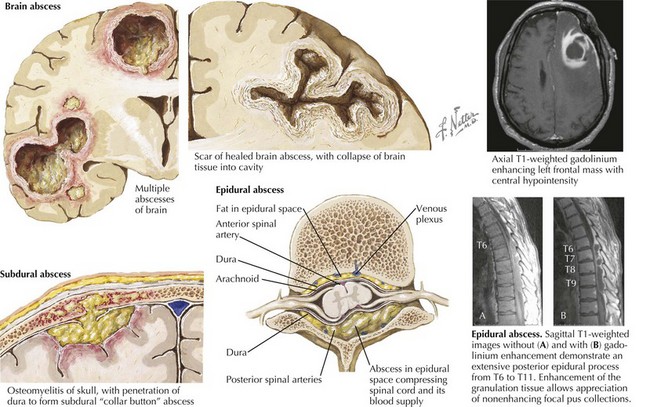

The most important diagnostic procedure is brain imaging with contrast, either a CT or MRI (Figure 92-3). The advantages of CT scans are that they are quicker than MRIs and usually do not require sedation for the patient. On CT scans, abscesses appear as rim-enhancing, space-occupying lesions, often with surrounding cerebral edema. After an abscess is found, the patient should be evaluated by a neurosurgeon for drainage of the abscess. Samples should be sent from the operating room to a microbiology laboratory for Gram stain and aerobic and anaerobic culture.

Subdural Empyema

Epidural Abscess

Etiology, Epidemiology, and Pathogenesis

Epidural abscesses can occur either within the cranium or within the spinal canal (see Figure 92-3). The pathogenesis and infectious organisms associated with these infections vary according to the site of infection.

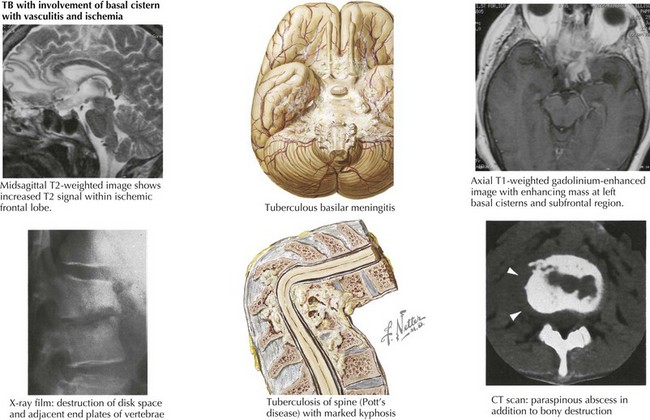

Other Infections—Tuberculosis Meningitis

Meningitis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is very uncommon in the developed world but has become more common in areas with a high prevalence of HIV infection (Figure 92-4). It usually occurs in children younger than 2 years of age with tuberculosis (TB) because they are at higher risk of developing extrapulmonary disease (lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, meningitis). In most cases, the child has a household contact or is in close contact with a caregiver who has active pulmonary TB, which is often undiagnosed.

Adame N, Hedlund G, Byington CL. Sinogenic intracranial empyema in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):e461-e467.

Auletta JJ, John CC. Spinal epidural abscesses in children: a 15-year experience and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(1):9-16.

Bair-Merritt MH, Chung C, Collier A. Spinal epidural abscess in a young child. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):E39.

Bair-Merritt MH, Shah SS, Zaoutis TE, et al. Suppurative intracranial complications of sinusitis in previously healthy children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(4):384-386.

Bockova J, Rigamonti D. Intracranial empyema. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(8):735-737.

Chavez-Bueno S, McCracken GHJr. Bacterial meningitis in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52(3):795-810. vii

Darouiche RO. Spinal epidural abscess. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):2012-2020.

de Gans J, van de Beek D. Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1549-1556.

Nguyen TH, Tran TH, Thwaites G, et al. Dexamethasone in Vietnamese adolescents and adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(24):2431-2440.

Osborn MK, Steinberg JP. Subdural empyema and other suppurative complications of paranasal sinusitis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(1):62-67.

Thwaites GE, Tran TH. Tuberculous meningitis: many questions, too few answers. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(3):160-170.

Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(9):1267-1284.