7 Infections of bone and joints

INFECTIONS OF BONE

Infection of bone by pyogenic organisms is termed osteomyelitis.1 It occurs in acute and chronic forms. The only other infections of bone with which the student in Western countries need concern himself are tuberculous infections, although syphilitic infections and fungal infections may still occur occasionally in other parts of the world.

ACUTE OSTEOMYELITIS (Acute pyogenic infection of bone; acute osteitis)

Two distinct types of acute osteomyelitis must be considered:

The two types are sufficiently distinct to require separate descriptions.

ACUTE HAEMATOGENOUS OSTEOMYELITIS

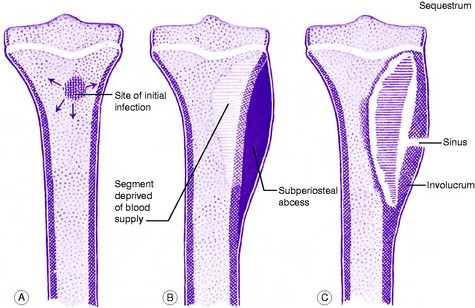

In the usual childhood manifestation, the infection begins in the metaphysis of a long bone, which must be presumed to form a productive medium for bacterial growth (Fig. 7.1A); thence it may spread to involve a large part of the bone. The organisms induce an acute inflammatory reaction, but the marshalling of the body’s defensive forces is greatly handicapped in bone because its rigid structure does not allow swelling. Pus is formed and soon finds its way to the surface of the bone where it forms a subperiosteal abscess (Fig. 7.1B); later the abscess may burst into the soft tissues and may eventually reach the surface to form a sinus.

Often the blood supply to a part of the bone is cut off by septic thrombosis of the vessels (Fig. 7.1B). The ischaemic bone dies and eventually separates from the surrounding living bone as a sequestrum (Fig. 7.1C). Meanwhile new bone is laid down beneath the stripped-up periosteum, forming an investing layer known as the involucrum (Fig. 7.1C).

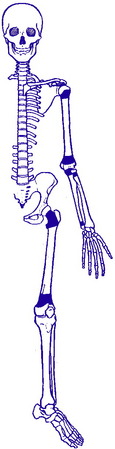

The epiphysial cartilage plate is a barrier to the spread of infection, but if the affected metaphysis lies partly within a joint cavity the joint is liable to become infected (acute pyogenic arthritis). Metaphyses that lie wholly or partly within a joint cavity include the upper metaphysis of the humerus, all the metaphyses at the elbow, and the upper and lower metaphyses of the femur (Fig. 7.2). Even when the joint is not infected it may swell from an effusion of clear fluid (sympathetic effusion).

Clinical features. Except for rare exceptions acute haematogenous osteomyelitis is confined to children, especially boys. The bones most commonly affected are the tibia, the femur and the humerus. The onset is rapid. The child complains of feeling ill, and of severe pain over the affected bone. There may be a history of recent boils or of a minor injury.

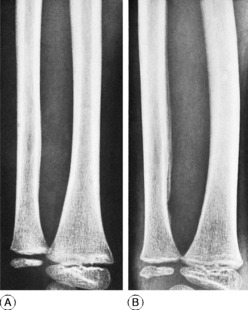

Imaging. Radiographic examination in the early stage does not show any alteration from the normal (Fig. 7.3A). Only after two or three weeks do visible changes appear, and they may never do so if efficient treatment is started very early. The important changes are diffuse rarefaction of the metaphysial area and new bone outlining the raised periosteum (Figs 7.3B and 7.4).

Radioisotope scanning with 99mtechnetium is reserved for the diagnosis of bone infection in the less clinically accessible sites such as the hip, pelvis and spine. Accumulation of isotope depends upon the rate of bone turnover and its vascularity, so that in the early stages of disease inadequate blood supply may result in a ‘cold’ lesion. More commonly, within a few hours or days of the onset of symptoms there is an increased uptake of isotope, giving a ‘hot’ scan at the site of the bone lesion. In the more obscure low-grade infections associated with prostheses and other surgical implants in bone, scanning with re-injected leucocytes labelled with 111mindium may provide improved diagnostic accuracy.

Acute osteomyelitis may also be confused with rheumatic fever, and, in infants, with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) (p. 80). Whenever possible the causative organism must be identified bacteriologically. It is important that blood for culture be taken before antibiotic therapy is commenced.

Complications. The important complications are:

Acute osteomyelitis often passes into a state of chronic infection.

Treatment. Efficient treatment must be begun at the earliest possible moment.

Local treatment. The question of operation and its timing is still controversial. Operation may be unnecessary if effective antibiotic treatment can be begun within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, and this should always be the aim. But in practice diagnosis is not always so prompt, and in that event it seems wiser to undertake early operation, in order to release pus and to relieve pain, which is often severe. This should definitely be performed if there has not been a marked improvement to the antibiotic treatment within 48 hours. Release of pus may also reduce the risk of ischaemic bone necrosis; and furthermore it allows the organism to be identified and its sensitivity to antibiotics determined. An incision at the site of maximum tenderness is made down to the bone and subperiosteal pus is evacuated. It is advisable – though not always essential – to make one or two drill holes through the cortex to improve medullary drainage. In most cases the wound may safely be sutured. Thereafter the limb is splinted until the infection is overcome.

CHRONIC OSTEOMYELITIS (Chronic pyogenic osteomyelitis)

Clinical features. The main symptom is usually a purulent discharge from a sinus over the affected bone. In other cases pain is the predominant feature which brings the patient to the doctor. Discharge of pus may be continuous or intermittent. Reappearance of a sinus that has been healed for some time is heralded by local pain, pyrexia, and the formation of an abscess. This is termed a ‘flare-up’, or ‘flare’, of infection.

Imaging. Radiographic examination: The bone is often thickened and shows irregular and patchy sclerosis which may give a honeycombed appearance. If a sequestrum is present it is seen as a dense loose fragment, with irregular but sharply demarcated edges, lying within a cavity in the bone (Fig. 7.6). Radioisotope scanning may show increased uptake in the vicinity of the lesion. In diffuse disease MRI and CT scanning may be of value for localisation of abscess cavities and sequestra, thus allowing accurate planning of operative treatment.

Treatment. An acute flare-up of chronic osteomyelitis often subsides with rest and antibiotics. If an abscess forms outside the bone it must be drained. If there is a persistent and profuse discharge of pus a more extensive operation is advised. The aim should be to remove fragments of infected dead bone (sequestra) and to open up or ‘saucerise’ abscess cavities by chiselling away the overlying bone. Sometimes it is possible to obliterate a cavity with a flap of muscle, or to exteriorise it and line its walls directly with split-skin grafts. The principles of treatment are (1) remove dead and foreign material, (2) obliterate dead space, (3) if necessary, stabilise the skeleton, (4) obtain soft tissue cover, (5) if necessary, reconstruction of the bone defect, (6) possible appropriate antibiotic cover.

TUBERCULOUS INFECTION OF BONE

Tuberculosis of a vertebra

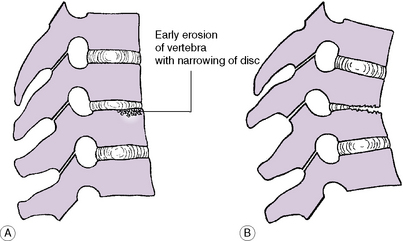

The infection typically affects the vertebral body. It may arise initially in the bone (Fig. 7.8A) or it may spread to the vertebra from the adjacent intervertebral disc. Tuberculous vertebral bodies collapse anteriorly but often retain their full depth behind, thereby becoming wedge-shaped (Fig. 7.8B). An abscess usually tracks downwards along the vertebral column; it may also extend backwards towards the spinal canal, where it may interfere with the function of the spinal cord.

Juxta-articular tuberculosis

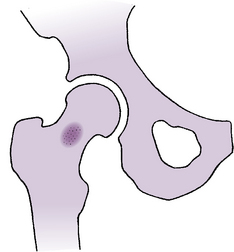

The articular ends of bones are frequently eroded by tuberculosis beginning primarily in the joint. Less often there is an isolated focus of infection within the bone (Fig. 7.9). From such a lesion the infection may spread eventually to the neighbouring joint.

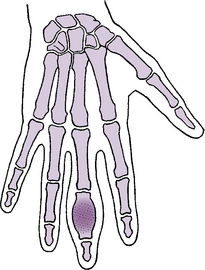

Bony tuberculosis in the hand or foot

The metacarpals or phalanges are the bones most commonly affected (tuberculous dactylitis). Characteristically the bone is enlarged by a fusiform swelling which at first represents thickened and raised periosteum. Later, much of the original bone is destroyed, but at the same time new bone is laid down beneath the expanded periosteum, giving the affected metacarpal or phalanx a ‘distended’ appearance (Fig. 7.10). Similar changes may affect a bone of the foot, or occasionally a long bone.

Clinical features. There is usually evidence of constitutional ill health. The local symptoms and signs depend upon the site of the infection. In general, pain is the initial symptom; and at most sites it is associated with obvious swelling and often with the formation of a ‘cold’ abscess. When the bone lesion is associated with tuberculous joint disease the joint symptoms predominate (see sections on the individual joints).

Imaging. The typical radiographic features of tuberculous infection of bone are:

On radioisotope scanning there is increased uptake of isotope in the vicinity of the lesion.

Treatment. In most instances tuberculosis of bone is associated with infection of a joint, and the treatment is mainly that of the joint lesion (tuberculous arthritis, p. 98). The treatment of an isolated tuberculous focus in bone is along similar lines, main reliance being placed upon a combination of antituberculous drugs, usually rifampicin and isoniazid for a period of six months, as outlined on page 102. Local collections of pus should be removed by aspiration or, sometimes, by operative drainage followed by immediate suture of the wound. Resolution is indicated by improvement in the general health and weight, decrease of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and improved radiographic appearance.

SYPHILITIC INFECTION OF BONE

Syphilitic osteo-periostitis occurs when the diaphysis or body of a bone is infected by syphilis. There is usually a combination of osteitis and periostitis, although one or other may predominate. Osteo-periostitis often occurs with metaphysitis in infants (Fig. 7.11A); it may occur separately in older children with congenital syphilis (Fig. 7.11B), or in adults with acquired syphilis.

Investigations. The Wassermann reaction is positive.

Treatment. The bone lesions usually respond well to intensive antisyphilitic measures.

PYOGENIC ARTHRITIS (Infective arthritis; septic arthritis)

Pathology. The organisms may reach the joint by three routes:

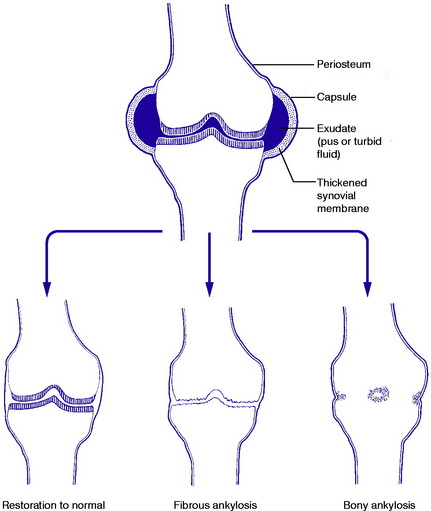

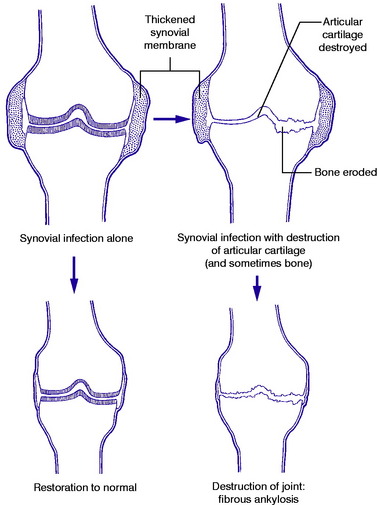

The infection causes an acute or subacute inflammatory reaction in the joint tissues. There is exudation of fluid within the joint: the fluid is turbid or frankly purulent according to the severity of the infection. The outcome varies from complete resolution, with normal function, to total destruction of the joint and fibrous or bony ankylosis (Fig. 7.12).

Clinical features. The onset is acute or subacute, with pain and swelling of the joint. There is constitutional illness, with pyrexia.

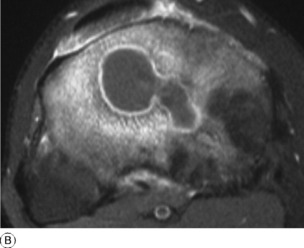

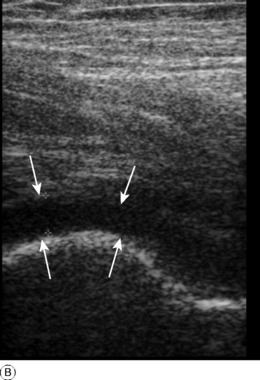

Imaging. Radiographs in the early stages do not show any alteration from the normal (Fig. 7.13A), though an ultrasound scan may reveal the presence of an effusion in the affected joint which can then be aspirated to aid diagnosis (Fig. 7.13B). Later, if the infection persists, there may be diffuse rarefaction of bone adjacent to the joint, loss of cartilage space, and possibly destruction of bone. Radioisotope bone scanning shows increased uptake of the isotope in the region of the joint.

Fig. 7.13 A Radiograph of pelvis in patient with an early septic arthritis of the right hip presenting with joint pain. There is an apparently normal radiographic appearance in both hips. B Ultrasound scan of the same hip demonstrating a joint effusion. The fluid in the joint is seen as a dark area (between the arrowheads).The lower arrows indicate the femoral head. Ultrasound is very sensitive to the presence of joint fluid and is the investigation of first choice in joint sepsis.

Prognosis. This varies widely according to the severity of the infection, the organism responsible, and the promptness with which efficient treatment is begun. Many joints can be saved intact, but many are destroyed more or less completely, with fibrous or bony ankylosis (Fig. 7.12).

TUBERCULOUS ARTHRITIS

In Britain the incidence of tuberculous arthritis, formerly common, decreased markedly in the years following the Second World War, probably because of the general improvement in living standards and the introduction of streptomycin and other antituberculous drugs. Pasteurisation of milk and elimination of infected cattle have virtually abolished bovine infection. In some Asiatic and African countries tuberculous infection is still common, and cases are now seen regularly among immigrants to Britain.

Pathology. No joint is immune, but the joints most often affected are the intervertebral joints of the thoracic or lumbar spine, and next in frequency the hip and knee. The organisms reach the joint through the blood stream from a focus elsewhere. The synovial membrane is much thickened (Fig. 7.14) by the tuberculous inflammatory reaction, which is of characteristic type, with round-cell infiltration and giant-cell systems. Unless the disease is arrested the articular cartilage is soon destroyed and the underlying bone is eroded. Sometimes the infection begins in bone adjacent to a joint rather than in the joint itself; thence it extends into the joint by direct continuity. The slow formation of an abscess – a ‘cold’ or chronic abscess in contradistinction to the florid abscess that may accompany an acute pyogenic infection – is a common feature. The abscess often makes its way towards the skin surface and may eventually rupture, giving rise to a chronic tuberculous sinus. This may provide a route for the entry of secondary infecting organisms.

If healing occurs before the articular cartilage and bone have been damaged the function of the joint is restored virtually to normal; but if cartilage or bone has been damaged before healing is secured permanent impairment – often complete loss of function – is inevitable (Fig. 7.15).

Imaging. Radiographic features. The earliest change in tuberculous arthritis is diffuse rarefaction throughout a fairly wide area of bone adjacent to the joint. If the disease is arrested early there may be no further change; but if the infection progresses the cartilage space is narrowed and the underlying bone is eroded (Fig. 7.15). As the disease heals the bones harden up again – that is, the rarefaction becomes gradually less apparent until the bone density is restored to normal.

Radioisotope bone scanning shows increased uptake of the isotope in the region of the joint.

Subsequent management depends on progress. If cartilage and bone are preserved intact and the local signs of inflammation subside, with improvement in the sedimentation rate, the outlook is good and activity may be progressively increased. If, however, the disease progresses to the point of eroding articular cartilage and underlying bone, a further period of immobilisation may be required, and fusion of the joint – usually by operation – may become the ultimate objective. In selected patients it may be feasible to undertake replacement arthroplasty of larger joints following successful antibacterial treatment. This should only be considered when the disease has been quiescent clinically for at least a year with a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

1 There is nothing to be gained by distinguishing between osteitis (inflammation of bone) and osteomyelitis (inflammation of bone and bone marrow). For practical purposes the two terms may be regarded as synonymous.

1 Sir Benjamin Brodie (1783–1862) English surgeon at St George’s Hospital London who was also President of the Royal Society. He described the clinical presentation and pathology of the lesion in 1832.