173 Infections in the Immunocompromised Host

• Neutropenia is a significant risk factor for infections in patients with malignant diseases. Empiric antibiotic therapy should be administered to all neutropenic febrile patients and to afebrile neutropenic patients who have new signs and symptoms consistent with infection.

• Neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count of less than 500 cells/mm3 or an absolute neutrophil count expected to decrease to less than 500 cells/mm3 during the next 48 hours.

• Splenectomized patients are at higher risk of fulminant infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Neisseria meningitidis.

• Prolonged corticosteroid therapy (>3 to 4 weeks) at doses of more than 20 mg per day places the patient at risk of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression and infectious complications.

• Malignant otitis externa, rhinocerebral mucormycosis, emphysematous pyelonephritis, emphysematous cholecystitis, and Fournier gangrene occur predominantly in diabetic patients.

Perspective

Immunocompromised patients frequently visit emergency departments (EDs) for evaluation and treatment of various conditions. Infectious complications are common, and they are a diagnostic priority because clinical presentations are often subtle and atypical. This chapter covers infections in patients with malignant disease, in patients receiving immunosuppressive and corticosteroid therapy, in patients who have undergone solid organ or bone marrow transplantation, and in diabetic patients. Human immunodeficiency virus infection is discussed in Chapter 175.

Malignancy, Neutropenia, and Fever

Epidemiology

Fever associated with neutropenia is often a presenting sign of infection in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer. Patients with severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count < 100 cells/mm3) or prolonged neutropenia (>7 days’ duration) are at higher risk of bacteremia.1

Pathophysiology

Patients with malignant diseases are predisposed to infections from various organisms, including bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens. Patients with malignant disease are more prone to infections because of impairment of normal host defenses (e.g., neutropenia associated with acute leukemia), complications associated with tumor growth and spread (e.g., bronchial obstruction from bronchogenic carcinoma that results in pneumonia), the use of chemotherapeutic agents and corticosteroids, a history of splenectomy, and infections associated with intravascular catheters or other implanted devices.2

Neutropenia is a significant risk factor for infections in patients with malignant disease, and it can be a result of the condition itself (e.g., acute leukemia) or a consequence of the myelosuppressive effects of agents used in disease management. The 2010 guidelines of the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer defined neutropenia as an absolute neutrophil count of less than 500 cells/mm3 or an absolute neutrophil count expected to decrease to less than 500 cells/mm3 during the next 48 hours.1 The frequency and severity of infection are inversely proportional to the neutrophil count, and susceptibility to infection increases when the neutrophil count falls to less than 1000 cells/mm3.3 In addition, vulnerability to infection increases with longer periods of neutropenia. The same guidelines also defined fever, in the absence of obvious environmental causes, as a single oral temperature measurement of 38.3° C (101° F) or higher or a temperature of 38.0° C (100.4° F) or higher for at least 1 hour.1

In addition to the neutrophils, other components of cell-mediated immunity, such as lymphocytes, monocytes, or macrophages, may also become deficient or defective in certain types of cancers (e.g., lymphoma, leukemia, Hodgkin disease). Many organisms may be responsible for infections in patients with these types of cancers that impair cell-mediated immunity2 (Box 173.1). These patients most often undergo an extensive work-up to establish the etiologic agent of infection. Special attention also needs to be paid to patients who have undergone splenectomy. These patients are at a higher risk of developing fulminant infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Neisseria meningitidis.

Approximately 60% of bacterial infections are the result of gram-positive cocci, and 35% are caused by gram-negative bacilli.2 Bacteremia complicates approximately 20% of the infections. The most common causes of bacteremia in febrile neutropenic patients are listed in Box 173.2.1,4 Anaerobes are uncommon culprits of infection in neutropenic patients, except in the presence of clinical features of oral mucositis or perirectal or intraabdominal infections.2,5

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Medical Decision Making

The initial evaluation often includes broad diagnostic testing, including serum chemistry studies, complete blood cell count, liver and renal function tests, urinalysis, blood and urine cultures, and radiographic evaluations (e.g., plain chest radiographs). Blood cultures should be drawn before the initiation of antimicrobial therapy. When a catheter-related infection is suspected, blood cultures should be simultaneously drawn through the central venous catheter and the peripheral vein.6 Urine cultures are especially indicated if the patient has signs and symptoms of urinary tract infection, if a urinary catheter is present, or if the urinalysis results are abnormal. A chest radiograph is indicated if the patient has any respiratory abnormalities or chest discomfort. A negative chest radiograph does not rule out the presence of a pulmonary infection in a neutropenic patient. In this population of patients, multiple studies have shown that high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scanning of the chest is a better diagnostic test than plain chest radiographs for the early detection of pneumonia.7–9 Unless clinically indicated, routine lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid examination are not recommended.4

Treatment

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be administered promptly to all neutropenic febrile patients and to afebrile neutropenic patients who have signs and symptoms consistent with infection. Box 173.3 depicts recommended initial antimicrobial therapy for the management of febrile neutropenic patients.1,4,5 The 2010 IDSA guidelines1 advocated that high-risk patients should receive intravenous antimicrobial monotherapy with any one of these agents: piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, meropenem, or imipenem. Other antimicrobials such as vancomycin or metronidazole can be added in the presence of specific clinical situations (see Box 173.3).

Box 173.3 Recommended Initial Antimicrobial Therapy for the Management of Febrile Neutropenic Patients*

Intravenous Therapy

Piperacillin-tazobactam or cefepime or ceftazidime or antipseudomonal carbapenem (e.g., imipenem, meropenem)

Vancomycin if any one of the following clinical situations exists: suspected catheter-related infection, skin and soft tissue infection, pneumonia, hemodynamic instability

Metronidazole if either of the following clinical situations exists: abdominal or Clostridium difficile infections

* Selection of the empiric regimen should be based on knowledge of the local antibiotic susceptibility pattern, prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and other resistant organisms within the community, and potential drug interactions and toxicities within each patient.

† Indicated only for low-risk patients (see text and Box 173.4).

When a catheter-related infection is suspected, empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy with vancomycin should be initiated6 (see Box 173.3). Peripheral venous catheters should be removed if the patient shows signs of infection at the site (e.g., drainage of pus, erythema) or evidence of septic shock with no other source of infection. Prompt removal of the catheter is warranted when intravascular catheterization is complicated by septic thrombophlebitis.6 The diagnosis can be made by ultrasonography with color Doppler imaging. Emergency physicians (EPs) should involve the oncologist and the infectious disease specialists in the decision-making process when considering removal of a central line.

Antiviral agents should not be initiated empirically as initial therapy in the ED for all patients with neutropenic fever. However, the presence of lesions resulting from herpes simplex virus or varicella-zoster virus warrants the initiation of antiviral agents (e.g., acyclovir, valacyclovir), even if these pathogens are not suspected as the cause of fever.1 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is an uncommon cause of fever in neutropenic patients, unless these patients undergone bone marrow transplantation. Empiric use of granulocyte or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor transfusions is not recommended for the treatment of established fever and neutropenia.1

Antifungal agents (e.g., amphotericin B) should not be initiated empirically in the ED as initial therapy for all patients with neutropenic fever. When antifungal agents are considered, administration is best done in consultation with specialists. In patients with persistent fever (≥4 days) despite adequate antimicrobial therapy and in whom no specific cause of infection has been found, empiric antifungal therapy is often initiated by the specialists.1

Admission

In general, almost all febrile neutropenic patients should be admitted to the hospital (in isolation) for intravenous antibiotic therapy and continued diagnostic work-up. Numerous studies, mostly in adult patients, have examined the identification of variables and scoring indexes that predict a low risk of severe infection among febrile neutropenic patients10–12 (Box 173.4). The most current IDSA guidelines recommended consideration of oral therapy only in low-risk adults who can be vigilantly observed and who have timely access to continued medical care.1 If outpatient therapy is considered, EPs should always involve the oncologist and the infectious disease specialists in the decision-making process.

Box 173.4 Factors Associated with a Lower Risk of Complications and a Favorable Prognosis in Adult Patients Presenting with Neutropenic Fever

Absolute neutrophil and monocyte counts 100 cells/mm3 or higher

Age less than 60 and more than 16 years

Cancer in partial or complete remission

No symptoms or only mild to moderate symptoms of illness

Outpatient status at the time of fever onset

Temperature lower than 39.0° C

Normal findings on chest radiographs

Respiratory rate of up to 24 breaths per minute

Absence of chronic pulmonary diseases and diabetes mellitus

Absence of confusion or other signs of mental status alteration

Absence of blood loss and dehydration

No history of fungal infection or receipt of antifungal therapy during the 6 months before presentation with fever

Immunosuppressive and Corticosteroid Therapy

Chemotherapeutic agents induce variable degrees of myelosuppression. These agents can affect both the number and function of various cell lines such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages. The effect depends on the type of agent and the duration of exposure. Immunosuppression can be prolonged even after completion of therapy. The potential organisms and treatment of neutropenic fever associated with treatment-induced immunosuppression mirror the condition itself (see Boxes 173.1 to 173.3).

Like antitumor agents, corticosteroids can induce myelosuppression of various cell lines (e.g., lymphocytes, macrophages, immunoglobulins) and can increase the patient’s susceptibility to infections by various types of organisms. The risk of infection is directly related to the underlying condition, the dose of corticosteroid, and the duration of therapy.13 Prolonged treatment (>3 to 4 weeks) at doses of more than 20 mg per day places the patient at risk for hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression and infectious complications.13 In addition to pyogenic bacteria, infections can also involve Mycobacterium, Aspergillus, and Listeria species.14 Because steroids can suppress fever, the absence of fever does not exclude the possibility of infection. Fever in patients who are receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy is infectious in origin until proven otherwise.

Solid Organ Transplantation

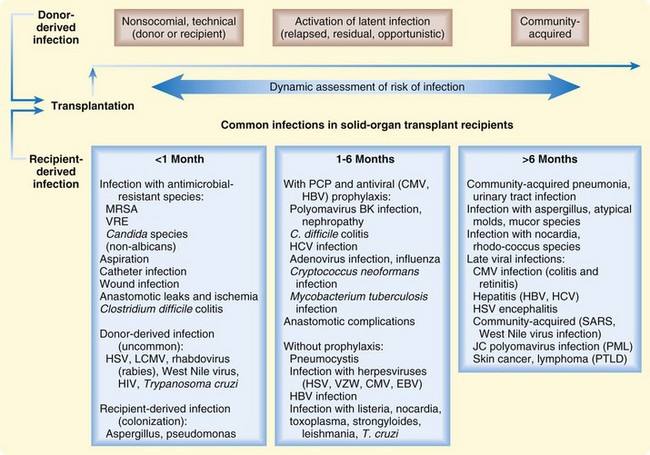

All recipients of solid organ transplants undergo similar immunosuppressive therapies after transplantation, and as a result of these standardized regimens, a predictive temporal pattern of infections (i.e., timetable of infections) is recognized (Fig. 173.1).15,16 This posttransplantation timetable is best divided into three periods: the first month, 1 to 6 months, and more than 6 months after transplantation. Opportunistic pathogens (e.g., Pneumocystis jiroveci [formerly Pneumocystis carinii], Aspergillus fumigatus, Listeria monocytogenes, Nocardia asteroides) are more likely to cause infections during the period from 1 to 6 months after transplantation. Prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jiroveci and CMV has reduced the incidence of infection by these organisms in transplant recipients.

Fig. 173.1 Timeline of common infections in solid organ transplant recipients.

(From Fishman JA. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2601–14.)

Of all the pathogens, CMV is the single most important infectious agent affecting the recipients of solid organ transplants.15,17 The onset of infection is usually after the first month of transplantation. The clinical presentation is variable and can range from flulike illness (e.g., fever, myalgia) to pneumonitis and encephalitis. Laboratory abnormalities can include leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, mild atypical lymphocytosis, and mild hepatitis. The transplanted organ is more susceptible to infection by CMV than are native organs. CMV also has immunosuppressive properties that can render patients more susceptible to opportunistic infections.15,17 The diagnosis is made by either tissue biopsy or demonstration of viremia. For a symptomatic patient with a confirmed diagnosis, the treatment of choice is intravenous ganciclovir.

Bone Marrow Transplantation

As in solid organ transplantation, a predictive temporal pattern of host defense defects and infectious complications occurs after bone marrow transplantation. This timetable is also best divided into three periods: the first 30 days, from 31 to 100 days, and more than 100 days after transplantation.18

The first 30 days are associated with profound leukopenia, often coupled with absolute neutropenia and lymphocytopenia. During this period, bacteremia is the most common identifiable infectious complication. The bacterial causes and the management of bacterial infections are similar to those seen in other neutropenic patients (see Boxes 173.2 and 173.3). Candida, Aspergillus, and recurrent herpes infections are also common causes of infection during this period.18

The second period, from 31 to 100 days after bone marrow transplantation, is more notable for defects in humoral and cell-mediated immunity. Leukopenia during this stage is less profound when compared with the earlier period after transplantation. Acute GVHD typically occurs during this time frame, thus prolonging the state of immunosuppression. Many organisms can cause infections in this period (see Boxes 173.1 and 173.2). The most common cause of severe viral illness during this period is CMV, which can lead to interstitial pneumonitis characterized by fever, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates, hypoxia, and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Treatment of CMV pneumonia includes intravenous ganciclovir and CMV immunoglobulin.

The development of chronic GVHD and a delay in the development of humoral and cell-mediated immunity contribute to infectious complications during the third period (i.e., >100 days) after transplantation. Common bacterial organisms causing infections in this period include encapsulated organisms such as S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae. Candida, Aspergillus, and varicella-zoster virus are also common causes of infection during this time frame.18

Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus affects several aspects of the immune system. Functional properties of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes such as adherence, chemotaxis, and phagocytosis are depressed in patients with diabetes. These effects are exaggerated in patients with concomitant acidosis. Other alterations in the immune system can include reduced cell-mediated immune responses, impaired pulmonary macrophage function, and abnormal delayed-type hypersensitivity responses. No significant alternations are shown to occur with humoral immunity.19,20

Certain community-acquired infections are more common in patients with diabetes (e.g., lower respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, skin and mucous membrane infections). The risk of recurrence of such infections is also higher in diabetic patients. Some specific types of infections also occur predominantly in diabetic patients (e.g., malignant otitis externa, rhinocerebral mucormycosis, emphysematous pyelonephritis and cholecystitis, Fournier gangrene).19,20

Emphysematous Pyelonephritis

Emphysematous pyelonephritis is a life-threatening, fulminant, suppurative, and necrotizing infection involving the renal parenchyma and perirenal tissues. The disease occurs primarily in diabetic patients and in women more frequently than in men, and it more often involves the left kidney.21 Patients frequently present in severe sepsis or septic shock. Emphysematous pyelonephritis can be complicated by obstruction of the renoureteral system and by the presence of renal or ureteral stones.

The diagnosis is confirmed radiographically by demonstration of gas in the renal parenchyma or perinephric space. The imaging modality of choice is noncontrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis. Intravenous contrast studies can be obtained for better delineation of abscess or vascular structures. Although plain film radiography may show the presence of renal calculi or gas, radiography is of limited value because of its inability to reveal detail. Renal ultrasound scanning is inferior to CT scanning for the localization of gas. Precise localization of gas is important in the differentiation of emphysematous pyelonephritis from emphysematous pyelitis (gas confined to the collecting system).21 Therapeutically, the distinction between the two disorders is crucial. Emphysematous pyelonephritis usually requires nephrectomy, whereas emphysematous pyelitis often requires medical management, with a drainage procedure only if it is associated with obstruction.21

Common organisms isolated from cultures of urine, blood, or aspirate material in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis include Escherichia coli (most common), Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus species, and P. aeruginosa. Management includes intensive resuscitation, initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and immediate surgical consultation and intervention. Antimicrobial therapy can include a combination of a β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor antibiotic with antipseudomonal activity (e.g., piperacillin-tazobactam) and an aminoglycoside (e.g., gentamicin). Surgical measures depend on the condition of the patient and the extent of disease and can include percutaneous catheter drainage, incision and drainage, or nephrectomy. Early surgical intervention (e.g., drainage, nephrectomy) in combination with broad-spectrum antibiotics has decreased mortality from emphysematous pyelonephritis.22,23

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Soft tissue infections in diabetic patients frequently involve the feet. The most common factor predisposing patients to diabetic foot infection is foot ulceration, and it is often related to peripheral neuropathy.24 Complications can include fulminant and life-threatening septicemia, osteomyelitis, fasciitis, and amputation.

Acute infections in patients with diabetic foot infections who have not recently received antibiotics are often monomicrobial infections with aerobic gram-positive cocci (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, ß-hemolytic streptococci). Chronic wounds or those that have been treated previously with antibiotics are polymicrobial infections commonly resulting from S. aureus, β-hemolytic streptococci, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and Bacteroides fragilis.19,24 Depending on the prevalence in the community, community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) should also be considered a culprit in these infections.25

The initial assessment should include plain radiography for the exclusion of foreign bodies and for evaluation of osteomyelitis.26 This study also serves as a baseline for future comparisons. The ability to see or touch bone with a sterile surgical probe suggests underlying osteomyelitis. Wound specimens for aerobic and anaerobic cultures, although not usually necessary for mild infections, are best obtained by biopsy, ulcer curettage, or aspiration and are preferred to swab specimen.24

Management of diabetic foot infection should include initiation of antimicrobial therapy, glycemic control, débridement of devitalized and necrotic tissue, application of sterile dressing, and off-loading pressure at the ulcer.19,24 The choice of antimicrobial therapy depends on the duration and the severity of the infection, the history of recent antibiotic therapy, the local antibiotic susceptibility pattern, and the prevalence of CA-MRSA and other resistant organisms within the community. Patients discharged home should have early follow-up to ensure proper wound healing.

Fournier gangrene, a form of necrotizing fasciitis involving the male genitalia, is typically seen in older diabetic patients. Clinical features can include crepitus, bullous skin lesions, pain out of proportion to physical findings, and marked systemic toxicity. The infection is most often polymicrobial, involving aerobic and anaerobic streptococci, S. aureus, E. coli, Pseudomonas, Clostridium, and Bacteroides species.20 Early recognition, hemodynamic stabilization, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g., vancomycin plus piperacillin-tazobactam plus clindamycin), and emergency surgical débridement are the mainstays of therapy. Other potential adjunctive therapeutic modalities such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy should not take precedence over early surgical intervention.

Tips and Tricks

Malignancy, Neutropenia, and Fever

• Suspect occult infection when a patient complains of pain in any bodily area despite the absence of signs of infection.

• Pay special attention to the oral cavity, perineum, toes, bone marrow aspiration sites or sites, and vascular catheters for signs of infection.

• Look for a splenectomy scar. Splenectomized patients are at a higher risk of infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis.

Fishman JA. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2601–2614.

Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e56–e93.

Grayson ML, Gibbons GW, Balogh K, et al. Probing to bone in infected pedal ulcers: a clinical sign of underlying osteomyelitis in diabetic patients. JAMA. 1995;273:721–723.

Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45.

1 Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e56–e93.

2 Bodey GP. Infections associated with malignancy. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR. Infectious diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:1106–1111.

3 Bodey GP, Buckley M, Sathe YS, et al. Quantitative relationships between circulating leukocytes and infection in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Intern Med. 1966;64:328–340.

4 Zinner SH. Treatment and prevention of infections in immunocompromised hosts. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR. Infectious diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:1141–1150.

5 Barg NL, Fekety R. Infections associated with corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR. Infectious diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:1129–1140.

6 Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45.

7 Heussel CP, Kauczor HU, Heussel GE, et al. Pneumonia in febrile neutropenic patients and in bone marrow and blood stem-cell transplant recipients: use of high-resolution computed tomography. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:796–805.

8 Heussel CP, Kauczor HU, Heussel G, et al. Early detection of pneumonia in febrile neutropenic patients: use of thin-section CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1347–1353.

9 Barloon TJ, Galvin JR, Mori M, et al. High-resolution ultrafast chest CT in the clinical management of febrile bone marrow transplant patients with normal or nonspecific chest roentgenograms. Chest. 1991;99:928–933.

10 Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, et al. The multinational association for supportive care in cancer risk index: a multinational scoring system for identify low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3038–3051.

11 Talcott JA, Siegel RD, Finberg R, et al. Risk assessment in cancer patients with fever and neutropenia: a prospective, two-center validation of a prediction rule. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:316–322.

12 Klaasseen RJ, Goodman R, Pham BA, et al. “Low-risk” prediction rule for pediatric oncology patients presenting with fever and neutropenia. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1012–1019.

13 Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:954–963.

14 Klein NC, Go CH, Cunha BA. Infections associated with steroid use. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:423–432.

15 Fishman JA, Rubin RH. Infection in organ-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1741–1751.

16 Fishman JA. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2601–2614.

17 Tolkoff-Rubin NE, Rubin RH. Infections in organ transplant recipients. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR. Infectious diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:1111–1123.

18 Mannick J, Ellison RT. Infections associated with bone marrow transplantation. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR. Infectious diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:1123–1128.

19 Joshi N, Caputo GM, Weitekamp MR, et al. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1906–1912.

20 Rajagopalan S. Serious infections in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:990–996.

21 Evanoff GV, Thompson CS, Foley R, et al. Spectrum of gas within the kidney: emphysematous pyelonephritis and emphysematous pyelitis. Am J Med. 1987;83:149–154.

22 Abdul-Halim H, Kehinde EO, Abdeen S, et al. Severe emphysematous pyelonephritis in diabetic patients: diagnosis and aspects of surgical management. Urol Int. 2005;75:123–128.

23 Huang JJ, Tseng CC. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: clinicoradiological classification, management, prognosis, and pathogenesis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:797–805.

24 Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:885–910.

25 Tentolouris N, Petrikkos G, Vallianou N, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in infected and uninfected diabetic foot ulcers. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:186–189.

26 Grayson ML, Gibbons GW, Balogh K, et al. Probing to bone in infected pedal ulcers: a clinical sign of underlying osteomyelitis in diabetic patients. JAMA. 1995;273:721–723.