Chapter 171 Infections in Immunocompromised Persons

Infection and disease develop when the host immune system fails to adequately protect against potential pathogens. In persons with an intact immune system, infection occurs in the setting of naiveté to the microbe and no pre-existing microbe-specific immunity or when protective barriers of the body such as the skin have been breached. Healthy children are able to meet the challenge of most infectious agents with an immunologic armamentarium capable of preventing significant disease. Once an infection begins to develop, an array of immune responses is set into action to control the disease and prevent it from reappearing. In contrast, immunocompromised children might not have this same capability. Depending on the level and type of immune defect, the affected child might not be able to contain the pathogen or to develop an appropriate immune response to prevent recurrence (Chapter 116).

Primary immunodeficiencies are compromised states that result from genetic defects affecting one or more arms of the immune system (Table 171-1). Acquired, or secondary, immunodeficiencies may result from infection (e.g., infection with HIV), from malignancy, or as an adverse effect of immunomodulating or immunosuppressing medications. Such immunosuppressing medications include medications that affect T cells (steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and chemotherapy), neutrophils (myelosuppressive agents, idiosyncratic or immune-mediated neutropenia), or all immune cells (chemotherapy). Perturbations of the mucosal and skin barriers or normal microbial flora can also be characterized as secondary immunodeficiencies, leaving the host open to infections, if only for a temporary period.

Table 171-1 MAJOR CAUSES OF INCREASED RISK FOR INFECTION IN IMMUNOCOMPROMISED HOSTS

PRIMARY IMMUNODEFICIENCIES

Antibody deficiency (B-cell defects; Chapter 118)

Cell-mediated deficiency (T-cell defects; Chapter 119)

Combined B- and T-cell defects (Chapter 120)

Phagocyte defects (Chapter 124)

Leukopenia (Chapter 125)

Disorders of the complement system (Chapter 128)

SECONDARY IMMUNODEFICIENCIES

HIV

Malignancies (and cancer chemotherapy)

Transplantation

Burns

Sickle cell disease

Cystic fibrosis

Diabetes mellitus

Immunosuppressive drugs

Asplenia

Implanted foreign body

Malnutrition

The major pathogens causing infections among immunocompetent hosts are also the main pathogens responsible for infections among children with immunodeficiencies. In addition, less-virulent organisms, including normal skin flora, commensal bacteria of the oral pharynx or gastrointestinal (GI) tract, environmental fungi, and common community viruses of low-level pathogenicity, can cause severe, life-threatening illnesses in immunocompromised patients (Table 171-2). For this reason, close communication with the diagnostic laboratory is critical so that the laboratory does not disregard normal flora and organisms normally considered to be contaminants as being unimportant.

Table 171-2 MOST COMMON CAUSES OF INFECTIONS IN IMMUNOCOMPROMISED CHILDREN

BACTERIA, AEROBIC

BACTERIA, ANAEROBIC

FUNGI

VIRUSES

PROTOZOA

Listed alphabetically.

171.1 Infections Occurring with Primary Immunodeficiencies

Abnormalities of the Phagocytic System

Children with abnormalities of the phagocytic and neutrophil system have problems with bacteria as well as environmental fungi. Disease manifests as recurrent infections of the skin, mucous membranes, lungs, liver, and bones. Dysfunction of this arm of the immune system can be due to inadequate numbers, abnormal movement properties, or aberrant function of neutrophils (Chapter 124).

Neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count of <1,000 cells/mm3 and can be associated with significant risk for developing severe bacterial and fungal disease, particularly when the absolute count is <500 cells/mm3 (Chapter 125). Although acquired neutropenia secondary to bone marrow suppression from a virus or medication is common, genetic causes of neutropenia also exist. Primary congenital neutropenia most often manifests during the 1st year of life with cellulitis, perirectal abscesses, or stomatitis from Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Episodes of severe disease, including bacteremia or meningitis, are also possible. Bone marrow evaluation shows a failure of maturation of myeloid precursors. Most forms of congenital neutropenia are autosomal dominant, but some, such as Kostmann syndrome (Chapter 125) and Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (Chapter 462) are due to autosomal-recessive mutations. Cyclic neutropenia can be associated with autosomal-dominant inheritance or de novo sporadic mutations and manifests as fixed cycles of severe neutropenia between periods of normal granulocyte numbers. Often the neutrophil count has normalized by the time the patient presents with symptoms thus hampering the diagnosis. The cycles classically occur every 21 days (range, 14-36 days), with neutropenia lasting 3-6 days. Most often the disease is characterized by recurrent aphthous ulcers and stomatitis during the periods of neutropenia. However, life-threatening necrotizing myositis or cellulitis and systemic disease can occur, especially with Clostridium septicum or Clostridium perfringens. Many of the neutropenic syndromes respond to colony-stimulating factor.

Leukocyte adhesion defects are caused by defects in the β chain of integrin (CD18), which is required for the normal process of neutrophil aggregation and attachment to endothelial surfaces (Chapter 124). In the most-severe form there is a total absence of CD18. Children with this defect can have a history of delayed cord separation and recurrent infections of the skin, oral mucosa, and genital tract beginning early in life. Ecthyma gangrenosum and pyoderma gangrenosum also occur. Because the defect involves leukocyte migration and adherence, the neutrophil count in the peripheral blood is usually extremely elevated and pus is not found at the site of infection. Survival is usually <10 yr in the absence of stem cell transplantation.

Chronic granulomatous disease is an inherited neutrophil dysfunction syndrome, which can be either X-linked or autosomal recessive (Chapter 124). Neutrophils and other myeloid cells have defects in their nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase function, rendering them incapable of generating superoxide and thereby impairing intracellular killing. Accordingly, microbes that destroy their own hydrogen peroxide (S. aureus, Serratia marcescens, Burkholderia cepacia, Nocardia spp, Aspergillus) cause recurrent infections in these children. Infections have a predilection to involve the lungs, liver, and bone in these children. Prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, recombinant human interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and oral antifungal agents that have activity against Aspergillus spp such as itraconazole or newer azoles substantially reduce the incidence of severe infections. Patients with life-threatening infections have also been reported to benefit from aggressive treatment with white cell transfusions in addition to antimicrobial agents directed against the specific pathogen.

B-Cell Defects (Humoral Immunodeficiencies)

Antibody deficiencies account for the majority of primary immunodeficiencies among humans (Chapter 118). Patients with defects in the B-cell arm of the immune system fail to develop appropriate antibody responses, with abnormalities that range from complete agammaglobulinemia to isolated failure to produce antibody against a specific antigen or organism. Antibody deficiencies found in children with diseases such as X-linked agammaglobulinemia or common variable immunodeficiency predispose to infections with encapsulated organisms such as S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae type b. Other bacteria can also be problematic in these children (see Table 171-2). Even though most other classes of microbes do not cause problems for these patients, some notable exceptions exist. Rotavirus can lead to chronic diarrhea, and enteroviruses can disseminate and cause a chronic meningoencephalitis syndrome. Paralytic polio has developed after immunization with live polio vaccine. Protozoan infections such as giardiasis can be severe and persistent. Children with B-cell defects can develop bronchiectasis over time following chronic or recurrent pulmonary infections.

Selective IgA deficiency leads to a lack of production of secretory antibody at the mucosal membranes (Chapter 118). Even though most patients have no increased risk for infections, some have mild to moderate disease at sites of mucosal barriers. Accordingly, recurrent sinopulmonary infection and GI disease are the major clinical manifestations. These patients also have an increased incidence of allergies and autoimmune disorders compared with the normal population.

Hyper-IgM syndrome is caused by a defect in the CD40 ligand on the T cell and is associated with a deficiency in the production of IgG and IgA antibody (Chapter 118). In addition, recurrent neutropenia, hemolytic anemia, or aplastic anemia can be present. Similar to patients with agammaglobulinemia, these patients are at risk for bacterial sinopulmonary infections, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP), and Cryptosporidium intestinal infection.

T-Cell Defects (Cell-Mediated Immunodeficiencies)

Children with primary cell-mediated immunodeficiencies, either isolated or more commonly in combination with B-cell defects, present early in life and are susceptible to viral, fungal, and protozoan infections. Clinical manifestations include chronic diarrhea, mucocutaneous candidiasis, and recurrent pneumonia, rhinitis, and otitis media. In thymic hypoplasia (DiGeorge syndrome), hypoplasia or aplasia of the thymus and parathyroid glands occurs during fetal development in association with the presence of other congenital abnormalities (Chapter 119). Hypocalcemia and cardiac anomalies are usually the presenting features of DiGeorge syndrome, which should prompt evaluation of the T-cell system. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis is a rare immunodeficiency associated primarily with T-cell dysfunction. These patients might not demonstrate delayed hypersensitivity to skin tests for Candida antigen despite having chronic superficial infection with yeast, but they do not appear to be at increased risk for systemic yeast infections. Endocrinopathies are commonly associated with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis.

Combined B-Cell and T-Cell Defects

Patients with defects in both the T-cell and B-cell components of the immune system have variable manifestations depending on the extent of the defect (Chapter 120). Complete immunodeficiency is found with severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome (SCID), whereas partial defects can be present in such states as ataxia-telangiectasia, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, hyper-IgE syndrome, and X-linked immunodeficiency syndrome. Children with SCID present in the 1st 6 mo of life with recurrent, severe infections caused by a variety of bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Failure to thrive, chronic diarrhea, mucocutaneous or systemic candidiasis, PCP, or cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections are common early in life. Passive maternal antibody is relatively protective against the bacterial pathogens during the 1st few months of life, but thereafter patients are susceptible to both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms. Exposure to live virus vaccines can also lead to disseminated disease. Without stem cell transplantation, most affected children succumb to opportunistic infections within the 1st year of life.

Buckley RH. Primary immunodeficiency disease due to defects in lymphocytes. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1313-1324.

Ozkaynak MF, Krailo M, Chen Z, et al. Randomized comparison of antibiotics with and without granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the treatment of febrile neutropenia: a double blind placebo-controlled study in children: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:274-280.

Passive and active immunization. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, editors. Red book: 2009 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. ed 28. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:1-104.

171.2 Infections Occurring with Acquired Immunodeficiencies

Immunodeficiencies can be secondarily acquired as a result of infections or as a consequence of other underlying disorders such as malignancy, cystic fibrosis, diabetes mellitus, sickle cell disease, or malnutrition. Immunosuppressive medications used to prevent rejection after organ transplantation, to prevent graft versus host disease (GVHD) after stem cell transplantation (Chapter 131), or to treat malignancies can also leave the host vulnerable to infections. Similarly, medications used to control collagen vascular or other autoimmune diseases may be associated with an increased risk for developing infection. Any process that disrupts the normal mucosal and skin barriers (e.g., burns, surgery, indwelling catheters) can lead to an increased risk for infection.

Acquired Immunodeficiency from Infectious Agents

Infection with HIV, the causative agent of AIDS, is the most important infectious cause of acquired immunodeficiency (Chapter 268). Left untreated, HIV infection has profound effects on T-cell–mediated immunity that lead to susceptibility to the same types of infections as with primary T-cell immunodeficiencies (Table 171-3).

Table 171-3 DISEASES ESTABLISHED AS THE ETIOLOGY OF FEVER IN 70 CASES OF HIV-ASSOCIATED FEVER OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN

| ETIOLOGY | TIMES DIAGNOSIS WAS ESTABLISHED | |

|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |

| INFECTION | ||

| DMAC | 22 | 31 |

| PCP | 10 | 13 |

| CMV | 8 | 11 |

| Histoplasmosis | 5 | 7 |

| Viral (not CMV)* | 5 | 7 |

| Bacterial | 4 | 5 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 4 | 5 |

| Fungal (not histoplasmosis)† | 2 | 3 |

| Parasitic‡ | 2 | 3 |

| Mycobacterium genavense | 1 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 63 | 88 |

| NEOPLASIA | ||

| Lymphoma | 5 | 7 |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | 1 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 6 | 8 |

| MISCELLANEOUS | ||

| Drug fever | 2 | 3 |

| Castleman’s disease | 1 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 3 | 4 |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; DMAC, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PCP, Pneumocystis pneumonia.

* Includes hepatitis C, hepatitis B, adenovirus pneumonia, herpes simplex esophagitis, and varicella-zoster encephalitis (one case each).

† Includes disseminated cryptococcosis and pulmonary aspergillosis (1 case each).

‡ Includes cerebral toxoplasmosis and disseminated cryptosporidiosis (1 case each).

From Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases, ed 7, vol 1, Philadephia, 2010, Churchill Livingstone.

Malignancies

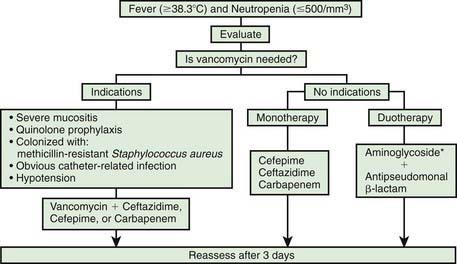

Even though several arms of the immune system can be affected, the major abnormality predisposing to infection in children with cancer is neutropenia. The degree and duration of neutropenia have long been relied upon as accurate predictors of the risk of infection in children being treated for cancer. Patients are at particular risk for bacterial infections if the absolute neutrophil count decreases to <500 cells/mm3. Counts of >500 cells/mm3 but <1,000 cells/mm3 incur some increased risk for infection but not nearly as great. The lack of neutrophils can lead to a loss of inflammatory response, and fever may be the only manifestation of infection. Accordingly, the absence of physical signs and symptoms is not always reliable, resulting in the need for empirical antibiotics (Fig. 171-1).

Because patients with fever and neutropenia might only have subtle signs and symptoms of infection, the presence of fever warrants a thorough physical examination with careful attention to the oropharynx (Table 171-4), lungs, perineum and anus, skin, nail beds, and intravascular catheter insertion sites. A comprehensive laboratory evaluation including a complete blood cell count, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and serum transaminases should be obtained. Blood cultures should be taken from each port of any central venous catheter. Consideration should also be given to obtaining a peripheral venous sample for blood culture, especially in children with ≥1 positive cultures from a central venous catheter, facilitating localization of the source of the infection. Other microbiologic studies should be done if there are associated clinical symptoms including nasal aspirate for viruses in patients with upper respiratory findings; stool for rotavirus in the winter months and for Clostridium difficile toxin in patients with diarrhea; urinalysis and culture in young children or in older patients with symptoms of urgency, frequency, dysuria, or hematuria; and biopsy and culture of cutaneous lesions. Chest radiographs should be obtained in any patient with lower respiratory tract symptoms, although pulmonary infiltrates may be absent in children with severe neutropenia. Sinus films should be obtained if rhinorrhea is prolonged. Abdominal CT scans should also be considered in children with profound neutropenia and abdominal pain to evaluate for the presence of typhlitis. Biopsies for cytology, Gram stain, and culture should be considered if abnormalities are found during endoscopic procedures or if lung nodules are identified radiographically.

Table 171-4 POSSIBLE CAUSES OF FEVER IN NEUTROPENIC PATIENTS NOT RESPONDING TO BROAD-SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS

| CAUSES | APPROXIMATE FREQUENCY IN HIGH-RISK PATIENTS (%) |

|---|---|

| Fungal infections susceptible to empirical therapy | 40 |

| Fungal infections resistant to empirical antifungal therapy | 5 |

| Bacterial infections (with cryptic foci, biofilms, and resistant organisms) | 10 |

| Toxoplasma gondii, mycobacteria, or fastidious pathogens (Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Bartonella) | 5 |

| Viral infections (herpesviruses, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza viruses) | 5 |

| Graft vs host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | 10 |

| Undefined (e.g., drug fever, toxic effects of chemotherapy, antitumor responses, undefined pathogens) | 25 |

From Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases, ed 7, vol 1, Philadephia, 2010, Churchill Livingstone.

Before the routine institution of empirical antimicrobial therapy for fever and neutropenia, 75% of children with fever and neutropenia were ultimately found to have a documented site of infection (see Table 171-4). Currently, gram-positive cocci are the most common pathogens; however, gram-negative organisms such as P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and Klebsiella can cause life-threatening infection and must be considered in the empirical treatment regimen. Other gram-negative pathogens such as Enterobacter and Acinetobacter are increasing in prevalence as well. While coagulase-negative staphylococci often cause infections in these children in association with central venous catheters, these infections are typically indolent, and a short delay in treatment usually does not lead to a detrimental outcome. Other gram-positive bacteria such as S. aureus and S. pneumoniae can cause more-fulminant disease and require prompt institution of therapy. Viridans streptococci are potential pathogens in patients with the oral mucositis that is often associated with use of cytarabine and in patients who experience selective pressure from treatment with certain antibiotics such as quinolones. Infection due to this organism can present as acute septic shock syndrome. Patients with prolonged neutropenia are at increased risk for opportunistic fungal infections, with Candida spp and Aspergillus spp being the most commonly identified fungi. Other fungi that can cause serious disease in these children include Mucor spp, Fusarium spp, and dematiaceous molds.

Fever and Neutropenia

The use of empiric antimicrobial treatment as part of the management of fever and neutropenia decreases the risk of progression to sepsis, septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, organ dysfunction, and death. In 2002, the Infectious Diseases Society of America published comprehensive guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic children and adults with cancer (see Fig. 171-1). First-line antimicrobial therapy should take into consideration the types of microbes anticipated and the local resistance patterns encountered at each institution. In addition, antibiotic choices may be limited by specific circumstances, such as the presence of drug allergy and renal or hepatic dysfunction. The empirical use of oral antibiotics is safe in some low-risk adults who have no evidence of bacterial focus or signs of significant illness (rigors, hypotension, mental status changes) and for whom a quick recovery of the bone marrow is anticipated. However, substantive data for this approach are lacking in children, and it is not currently recommended. The decision to use intravenous monotherapy versus an expanded regimen of antibiotics depends on the severity of illness of the patient, history of previous colonization with resistant organisms, and obvious presence of catheter-related infection. Vancomycin should be added to the empiric initial regimen if the patient has hypotension or other evidence of septic shock, an obvious catheter-related infection, or a history of colonization with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, or if the patient is at high risk for viridans streptococci (severe mucositis, acute myelogenous leukemia, or prior use of quinolone prophylaxis). Monotherapy with cefepime, ceftazidime, imipenem/cilastatin, meropenem, or piperacillin-tazobactam has been equally effective.

The use of antiviral agents in fever and neutropenia is not warranted without specific evidence of viral disease. Active herpes simplex or varicella-zoster lesions merit treatment to decrease the time of healing; even if these lesions are not the source of fever, they are potential portals of entry for bacteria and fungi. CMV is a rare cause of fever in children with cancer and neutropenia. If CMV infection is suspected, assays to evaluate viremia and organ-specific infection should be obtained. Ganciclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir may be considered while evaluation is pending, although ganciclovir can cause bone marrow suppression and foscarnet and cidofovir can be nephrotoxic (Chapter 247). If influenza is identified, specific treatment with antiviral agents should be administerd. Choice of treatment (oseltamivir, zanamivir, amantadine, or rimantadine) should be based on the anticipated susceptibility of the circulating influenza (Chapter 250).

The use of hematopoietic growth factors shortens the duration of neutropenia but has not been proved to reduce morbidity or mortality. Accordingly, the 2002 recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America do not endorse the routine use of hematopoietic growth factors in patients with uncomplicated fever and neutropenia. Infections occur in children with cancer even without neutropenia. Most often these organisms are viral in etiology. However, P. jiroveci can cause pneumonia (PCP) regardless of the neutrophil count. Prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole against PCP is an effective preventive strategy and should be provided to all children undergoing active treatment for malignancy (Chapter 236). Environmental fungi such as Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, and Coccidioides can also cause disease. Toxoplasma gondii is an uncommon but occasional pathogen in children with cancer. Infections encountered in healthy children (S. pneumoniae, group A streptococcus) can cause disease in children with cancer regardless of the granulocyte count.

Transplantation

Stem Cell Transplantation

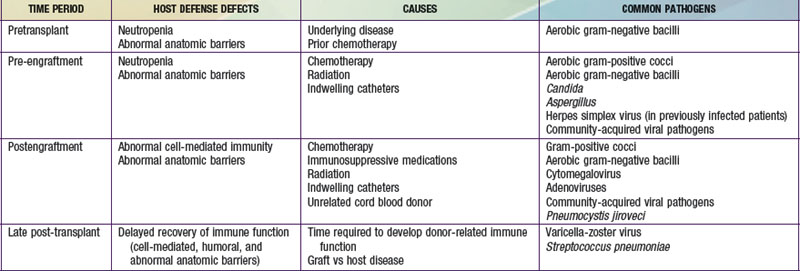

Infections following stem cell transplantation (SCT) can be classified as occurring during the pretransplantation period, pre-engraftment period (0-30 days after transplantation), postengraftment period (30-100 days), or late post-transplantation period (>100 days). Specific defects in host defenses predisposing to infection vary within each of these periods (Table 171-5). Neutropenia and abnormalities in cell-mediated and humoral immune function occur predictably during specific periods following transplantation. In contrast, breaches of anatomic barriers caused by indwelling catheters and mucositis secondary to radiation or chemotherapy create defects in host defenses that may be present anytime following transplantation.

Table 171-5 HOST DEFENSE DEFECTS AND COMMON PATHOGENS BY TIME AFTER BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION AND STEM CELL TRANSPLANTATION

Late Post-transplantation Period

Infection is unusual after 100 days in the absence of chronic GVHD. Chronic GVHD significantly affects anatomic barriers and is associated with defects in humoral, splenic, and cell-mediated immune function (Chapter 131). Viral infections, primarily reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV), are responsible for >40% of infections during this period. Bacterial infections, particularly of the upper and lower respiratory tract, account for ~30% of infections. These may be associated with deficiencies in immunoglobulin production, especially IgG2. Fungal infections account for <20% of confirmed infections during the late post-transplantation period.

Solid Organ Transplantation

Factors predisposing to infection after organ transplantation include those that either existed before transplantation or are secondary to intraoperative events or post-transplantation therapies (Table 171-6). Some of these additional risks cannot be prevented, and some risks acquired during or after the operation depend on decisions or actions of members of the transplant team. The necessity of using substantial immunosuppressive agents is the major factor predisposing to infection following transplantation. Despite efforts to develop optimal immunosuppressive regimens to prevent or treat rejection with minimal impairment of immunity, all current regimens interfere with the ability of the immune system to prevent infection. The majority of these immunosuppressive agents are aimed primarily at controlling cell-mediated immunity, but regimens can impair many other aspects of the transplant recipient’s immune system.

Table 171-6 RISK FACTORS FOR INFECTIONS FOLLOWING SOLID ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION IN CHILDREN

PRETRANSPLANTATION FACTORS

INTRAOPERATIVE FACTORS

POST-TRANSPLANTATION FACTORS

Timing

The timing of specific types of infections is generally predictable, regardless of which organ is transplanted (Table 171-7). Infectious complications typically develop in 1 of 3 time intervals: early (0-30 days after transplantation), intermediate (30-180 days, or 1-6 mo), and late (>180 days, or >6 mo); most infections develop in the 1st 180 days after transplantation. Table 171-7 should be used as a general guideline to the types of infections encountered but may be modified by newer immunosuppressive therapies and by the use of prophylaxis.

Table 171-7 TIMING OF INFECTIOUS COMPLICATIONS FOLLOWING SOLID ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION

EARLY PERIOD (0-30 DAYS)

Bacterial Infections

Gram-negative enteric bacilli

Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas, Alcaligenes

Gram-positive organisms

Fungal Infections

All transplant types

Viral Infections

Herpes simplex virus

Nosocomial respiratory viruses

MIDDLE PERIOD (1-6 MO)

Viral Infections

Cytomegalovirus

Epstein-Barr virus

Varicella-zoster virus

Pneumocystis jiroveci

Toxoplasma gondii

Bacterial Infections

Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas, Alcaligenes

Gram-negative enteric bacilli

LATE PERIOD (>6 MO)

Viral Infections

Epstein-Barr virus

Varicella-zoster virus

Community-acquired viral infections

Bacterial Infections

Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas, Alcaligenes

Gram-negative bacillary bacteremia

Fungal Infections

Adapted from Green M, Michaels MG: Infections in solid organ transplant recipients. In Long SS, Pickering L, Prober C, editors: Principles and practice of pediatric infectious disease, ed 3, New York, 2008, Churchill Livingstone.

Castagnola E, Fontana V, Caviglia I, et al. A prospective study on the epidemiology of febrile episodes during chemotherapy induced neutropenia in children with cancer or after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1296-1304.

Hernandez de Mezerville M, Tellier R, Richardson S, et al. Adenoviral infections in pediatric transplant recipients: a hospital-based study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:815-818.

Hughes WT, Armstrong D, Bodey GP, et al. 2002 guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:730-751.

171.3 Prevention of Infection in Immunocompromised Persons

Green M, Avery RK, Preiksaitis J. Guidelines for the prevention and management of infectious complications of solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(Suppl 10):1-166.

Segers P, Speekenbrink RGH, Ubbink DT, et al. Prevention of nosocomial infection in cardiac surgery by decontamination of the nasopharynx and oropharynx with chlorhexidine gluconate. JAMA. 2006;296:2460-2466.