5 Infection prevention and control in the PACU

Adverse Events: Untoward, undesirable, and usually unanticipated events, such as death of a patient, an employee, or a visitor in a health care organization. Incidents such as patient falls or improper administration of medications are also considered adverse events even if there is no permanent effect on the patient.

Airborne Transmission: (Microorganisms that are) carried or transported by the air.

Antibiotic Resistance: The selective pressure of antimicrobial therapy has resulted in the evolution of bacteria that are resistant to certain antibiotics. The resistance patterns of the microbes are constantly changing. These patterns are affected by patterns of antibiotic use, the prevalence of specific microorganisms, the mechanisms of resistance in these organisms, resistance transfer from one organism to another, and the patient population. The risk of infection or colonization with antibiotic-resistant microorganisms is higher among sicker and debilitated patients and in settings of high antimicrobial use and invasive technology (e.g., intensive care unit [ICU]). Infections from antibiotic-resistant organisms are difficult to treat and are often associated with high morbidity rates. These microbes can be spread from patient to patient through transient hand carriage and environmental contamination.

Antimicrobial Prophylaxis: Antibiotics that are given before the surgical incision for prevention of a surgical wound infection.

Artificial Nails: Nails with products affixed to them, such as gel, tips, jewelry, overlays, and wraps.

Attributable Mortality Rate: The death rate (expression of the number of deaths in a population during a specified time frame) that can be linked to a particular cause or source.

Barrier Precautions: The use of garb (e.g., masks, hair coverings, gowns, gloves) for protection to either the health care worker or the patient.

Bloodborne: Microorganisms that are carried or transmitted via the blood or fluids that contain blood.

Bloodborne Pathogens: Pathogenic microorganisms that are present in human blood and can cause disease in humans. These pathogens include, but are not limited to, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLA-BSI): Bacteremia or fungemia that develops in a patient with an intravascular central venous catheter.

Central Venous Catheter: A vascular access device that terminates at or close to the heart or one of the great vessels. An umbilical artery or vein catheter is considered a central line.

Chlorhexidine Gluconate (CHG): An antibacterial agent that is effective against a wide variety of gram-negative and gram-positive organisms and used as a topical antiinfective agent for the skin and mucous membranes.

Clostridium difficile: A bacterium that causes diarrhea and more serious intestinal conditions such as colitis. It is found in the normal gastrointestinal flora in about 3% of healthy adults and in 10% to 30% or more of hospitalized patients. Antibiotic use, even a short course given for prophylaxis or treatment of infections, often changes the normal gastrointestinal flora, which can lead to C. difficile overgrowth and toxin production. C. difficile accounts for 15% to 25% of all antibiotic-associated diarrhea. C. difficile colitis occurs in all ages but is most frequent in middle-aged and older adults or patients with debilitated conditions. C. difficile is shed in feces and is spread primarily via the hands of health care personnel who have touched a contaminated surface or item and via direct contact with a contaminated item. Hand hygiene performed with soap and water and thorough disinfection of the environment with diluted bleach reduce the risk of spreading C. difficile.

Colonization: Microorganisms that have become established in a habitat in a host but do not cause disease (infection) in this habitat.

Contact (Direct or Indirect): (Microorganisms that are) spread from contaminated hands or objects.

Contact Dermatitis: Inflammation of the skin that results from direct exposure to an irritant.

Contaminated Sharps: Any contaminated object that can penetrate the skin, such as needles, scalpels, broken glass, broken capillary tubes, and exposed ends of dental wires.

Cross Transmission: Horizontal transmission of an organism in the health care setting; patient to patient.

Disinfection: To render free from infection, especially with destruction of harmful microorganisms.

Droplet Transmission: (Microorganisms that are) carried on airborne droplets of saliva or sputum. In general they travel from 0 to 3 feet.

Epidemiology: A branch of medical science that deals with the incidence, distribution, and control of disease in a population.

Exposure Control Plan: A formal document as defined by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Regulations (Standards, 29 CFR) Bloodborne Pathogens 1910.1030; to exist in any institution with occupational exposure. The document is designed to outline the steps necessary to eliminate or minimize employee exposure.

Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases (ESBL): Beta-lactamase is a type of enzyme responsible for bacterial resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics; among these are penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, and others. In the middle 1980s, new types of beta-lactamase were produced by Klebsiella spp. and Escherichia coli that could hydrolyze the extended spectrum cephalosporins; these are collectively termed the extended spectrum beta-lactamases.

Fecal-Oral: Microorganisms that are spread through ingestion of contaminated feces.

Health Care–Associated Infections: Acquired or occurring in the health care setting.

Health Care Worker Flora: The microorganisms (as bacteria or fungi) that live in or on the bodies of personnel who work in a health care institution.

Hypothermia: Subnormal temperature of the body, defined as temperature less than 36° C.

Immunocompromised: Impairment or weakening of the immune system.

Medical Waste/Regulated Waste: Liquid or semiliquid blood or other potentially infectious materials; contaminated items that release blood or other potentially infectious materials in a liquid or semiliquid state if compressed; items that are caked with dried blood or other potentially infectious materials and are capable of releasing these materials during handling; contaminated sharps; and pathologic and microbiologic wastes that contain blood or other potentially infectious materials.

Microbial Colony Counts: Enumeration via direct count of viable isolated bacterial or fungal cells or spores capable of growth on solid culture media. Each colony (i.e., microbial colony-forming unit) represents the progeny of a single cell in the original inoculum. The method is used routinely by environmental microbiologists for quantification of organisms in air, food, and water; by clinicians for measurement of patient microbial load; and in antimicrobial drug testing.

Moist Body Substances: All body fluids, including blood, body cavity fluids, breast milk, urine, feces, wound or other skin drainage, respiratory and oral secretions, mucous membranes.

Mucous Membranes: Mucous membranes line cavities or canals of the body that open to the outside, including the eyes, ears, mouth, nose, and genitals.

Multidrug Resistant Organisms (MDROs): Microorganisms, predominantly bacteria, that are resistant to one or more classes of antimicrobial agents. Although the names of certain MDROs describe resistance to only one agent (e.g., methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA], vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus [VRE]), these pathogens are frequently resistant to most available antimicrobial agents. These highly resistant organisms deserve special attention in health care facilities. In addition to MRSA and VRE, certain gram-negative bacteria, including those that produce ESBLs and Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing organisms are of particular concern.

N95 Respirator: An air-purifying filtering-facepiece respirator that is more than 95% efficient at removing 0.3-μm particles and is not resistant to oil.

Negative-Pressure Isolation Rooms: The difference in air pressure between two areas. A room that is under negative pressure has a lower pressure than adjacent areas, which keeps air from flowing out of the room and into adjacent rooms or areas.

Normothermia: Normal body temperature (i.e., 36° to 38° C).

Nosocomial Infections: Term used historically to denote infections that are acquired or occur in a hospital.

One-Handed “Scoop” Technique: A method of capping a needle if deemed necessary to do so. The needle cap is set on a stable surface and not touched. The needled device then is placed inside the cap with one hand. The cap is then secured into place with the other hand.

Parenteral Exposure: Piercing of mucous membranes or the skin barrier through such events as needle sticks, human bites, cuts, and abrasions.

Pathogenic Microorganisms: An organism of microscopic or ultramicroscopic size that is capable of causing disease.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Specialized clothing or equipment worn by an employee for protection against a hazard. General work clothes (e.g., uniforms, pants, shirts, blouses) not intended to function as protection against a hazard are not considered to be PPE.

Seroconversion Risk: The likelihood of conversion from negative virus status to positive virus status.

Susceptible: Little resistance to a specific infectious disease.

Transient Contamination: A microorganism that exists temporarily on the hands of a health care worker and is not part of the normal flora of the skin.

Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus (VRE): A strain of Enterococcus species that normally lives in the intestines and sometimes the urinary tract of all people. VRE has learned to resist or survive most antibiotics, including a strong antibiotic called vancomycin. VRE is acquired via direct contact (touching) with objects or surfaces that are contaminated with VRE. VRE is not spread through the air. People at risk for VRE infection are those who have chronic illnesses, have undergone recent surgery, have weakened immune systems, or have recently taken certain antibiotics.

Managing the environment and equipment

Environment

A safe and clean environment is essential for a reduction in the risk of transmission of microorganisms. Most equipment in a perianesthesia unit that comes into contact with patients is considered to have a low risk of infection transmission, most notably if the equipment is noninvasive and contacts only intact skin. Examples of these items are electrodes, stethoscopes, pulse oximeter devices, blood pressure cuffs, the outside surfaces of equipment (e.g., ventilators, intravenous pumps), and larger surfaces (e.g., tables, wheelchairs, bedside stands, floors, walls). Depending on the item and the nature of the contamination, simple surface cleaning is all that is necessary to ensure safety between uses. Many hospital-grade disinfectants are combined with a cleaning component so that both cleaning and disinfection can be achieved in one step. Disinfection wipes are an appropriate option as well because of their active ingredient. If visible blood or body fluid is present, then a hospital-grade disinfectant approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (e.g., a quaternary ammonium compound, 70% isopropyl, properly diluted bleach, or phenolic) is required per the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogen Standard.1

Sinks

The number and accessibility of sinks in the perianesthesia care unit is important for increased compliance with hand washing. The Guidelines for Design and Construction of Hospital and Health Care Facilities, published and updated periodically by the American Institute of Architects (AIA), should be referenced for current sink allotment recommendations. The guidelines are conceived as minimal construction requirements for hospitals, and the document includes engineering systems, infection control, and safety and architectural guidelines for design and construction. The Joint Commission states that the AIA guidelines should be used during new construction. The current AIA guidelines recommend at least one hand washing station with hands-free or wrist blade–operable controls for every four beds in a postanesthesia care unit (PACU).2

General infection control practices

Handwashing

The benefits of hand hygiene in a hospital setting were first recognized by Ignaz Semmelweis in 1847 after the death of his friend from an infection that he contracted after his finger was accidentally punctured with a knife during a postmortem examination. The friend’s autopsy showed a pathologic situation similar to that of the women who were dying from puerperal fever in one of the obstetric clinics. Semmelweis immediately proposed a connection between cadaveric contamination and puerperal fever and made a detailed study of the mortality statistics of the obstetric clinic attended by physicians who also performed autopsies with the statistics of the midwives’ clinics. The midwives did not participate in autopsies. He concluded that he and the students carried the infecting particles on their hands from the autopsy room to the patients they examined in the clinical setting. Semmelweis concluded that some unknown “cadaveric material” caused childbed fever. He instituted a policy requiring use of a solution of chlorinated lime for washing hands between autopsy work and the examination of patients and the mortality rate dropped from 12.24% to 2.38%, comparable to the midwives’ clinics’ rates.3

To this day, hand hygiene remains of paramount importance for preventing the spread of disease-causing germs in the perianesthesia setting. Hands should be washed with soap and water for at least 15 to 20 seconds with a hospital-approved liquid or foam soap (bar soap should be avoided). If hands are not visibly soiled, an alcohol-based hand rub can be used. Alcohol-based hand rubs significantly reduce the number of microorganisms on the skin, are fast acting, and cause less skin irritation.4 They should not be used if the hands are visibly contaminated with blood, body fluids, or soiling. Hand hygiene should be minimally performed before and after patient care, after handling of soiled equipment or linen, after removal of gloves, after use of the restroom, before and after eating, or whenever hands are soiled. Health care personnel should avoid wearing artificial nails and keep natural nails less than one quarter of an inch long if they care for patients at high risk of acquiring infections (e.g., patients in intensive care units or in transplant units).

Adherence to hand hygiene practices has been studied in observational studies of health care workers (HCWs). Compliance rates to follow recommended hand hygiene procedures have been poor, with mean baseline rates of 5% to 81% (overall average, 40%). Perceived barriers to adherence with hand hygiene include skin irritation, inaccessible hand-hygiene supplies, interference with HCW-patient relationships, priority of care (i.e., the patient’s needs are given priority over hand hygiene), wearing of gloves, forgetfulness, lack of knowledge of hand hygiene policy, insufficient time for hand hygiene, high workload and understaffing, and the lack of scientific information or education indicating a definite effect of improved hand hygiene on health care–associated infection rates.5–11

Frequent and repeated use of hand hygiene products, particularly soaps and other detergents, is a primary cause of chronic irritant contact dermatitis among HCWs.12 To minimize this condition, HCWs should use hospital-approved hand lotion frequently and regularly on their hands. Small personal-use containers or multiuse pumps that are smaller than 16 ounces (and not refilled) should be used. Lotions that contain petroleum or other oil emollients can affect the integrity of latex gloves; therefore compatibility between the lotion and its possible effects on gloves should be considered at the time of product selection.1 Last, certain moisturizing products and surfactants have been shown to interfere with the residual activity of chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG), a skin antiseptic in liquid soap. Compatibility between a lotion and its possible effects on the efficacy of certain antiseptic soaps should be considered at the time of product selection.

Personal protective equipment

The most common personal protective equipment (PPE) used by HCWs is gloves. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended that HCWs wear gloves to: (1) reduce the risk of personnel acquiring infections from patients; (2) prevent HCW flora from being transmitted to patients; and (3) reduce transient contamination of the hands of personnel by flora that can be transmitted from one patient to another.13 OSHA mandates that gloves be worn during all patient care activities that may involve exposure to blood or body fluids that may be contaminated with blood.1 They should also be worn for direct contact with mucous membranes, nonintact skin, open wounds, or items potentially contaminated with moist body substances. Gloves should also be worn in vascular access procedures. The effectiveness of gloves in prevention of contamination of the hands of HCWs has been confirmed in several clinical studies. Two of these studies, which involved personnel caring for patients with Clostridium difficile or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), revealed that wearing gloves prevented hand contamination among most personnel who had direct contact with patients.14–16 Wearing of gloves also prevented personnel from acquiring VRE on their hands when touching contaminated environmental surfaces.16 Prevention of heavy contamination of the hands is considered important because hand washing or hand antisepsis might not remove all potential pathogens when hands are heavily contaminated.17,18

Standard precautions

Standard Precautions synthesize the major features of Universal Precautions (Blood and Body Fluid Precaution, designed to reduce the risk of transmission of bloodborne pathogens) and body substance isolation (designed to reduce the risk of transmission of pathogens from moist body substances) and apply to all patients who receive care in hospitals, regardless of diagnosis or presumed infection status. Standard Precautions apply to: (1) blood; (2) all body fluids, secretions, and excretions, except sweat, regardless of whether or not they contain visible blood; (3) nonintact skin; and (4) mucous membranes. Standard Precautions are designed to reduce the risk of transmission of microorganisms from both recognized and unrecognized sources of infection in hospitals.19

Management of the infected or contagious patient

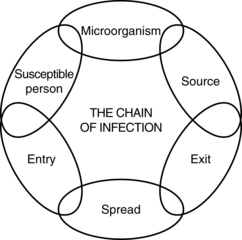

The chain of infection is a concept that shows the essential requirements for the perpetuation of a disease-causing microorganism (Fig. 5-1). All infectious diseases are caused by a microorganism (e.g., bacteria, virus, mold, fungi, parasite). For survival, each microorganism sustains itself in a source. The source may be a living host, such as a human or animal, or a nonliving source, such as biohazardous waste or a laboratory specimen. To cause disease, the microorganism must have a portal of exit from the source (e.g., respiratory tract, spill) and a method of spread. The six main methods of spread for infectious diseases include airborne, droplet, contact (direct or indirect), bloodborne, vector, and fecal-oral. With its unique method of spread, an organism must find a way to enter its next host. The entry point may be the same as the exit from the source of the infection (such as respiratory route to respiratory route or blood to blood), or it may be different (such as fecal exit to oral entry). The last component to the chain of infection is the susceptible person. A person may be more susceptible because of underlying illness, such as immunocompromise from chemotherapy or AIDS, or because of the risks of an open incision or invasive procedure. Likewise, a person may be less susceptible to the infection as a result of history of vaccination or natural immunity from past exposure or disease.

FIG. 5-1 Chain of infection.

(Courtesy The Department of Infection Control and Epidemiology at the University of Michigan Hospitals and Health Centers, Ann Arbor, Mich.)

Antibiotic-resistant organisms

In addition to the communicable diseases that pose an infectious risk to others, antibiotic-resistant organisms pose a significant threat to others if not properly controlled and managed. Aside from the cross-transmission risks, these organisms also cause an increase in lengths of stay, costs, and mortality rates.20–25 The most common organisms include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and VRE. Certain strains of S. aureus also have intermediate susceptibility or are resistant to vancomycin (i.e., vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus [VISA], vancomycin-resistant S. aureus [VRSA]). In addition to the gram-positive organisms are certain gram-negative bacteria, including those that produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) and others that are resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics. Examples of resistant gram-negative bacteria include E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii, and organisms such as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.

Patients who are vulnerable to colonization and infection include those with severe disease, especially those with compromised host defenses from underlying medical conditions; recent surgery; or indwelling medical devices (e.g., urinary catheters, endotracheal tubes). Hospitalized patients, especially patients in the ICU, tend to have more risk factors than nonhospitalized patients do and have the highest infection rates. Increasing numbers of infections with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) also have been reported to occur outside the ICU.26

Ample epidemiologic evidence suggests that MDROs are carried from one person to another via the hands of HCWs. Hands are easily contaminated during the process of care giving or from contact with environmental surfaces in close proximity to the patient. The latter is especially important when patients have diarrhea and the reservoir of the MDRO is the gastrointestinal tract. Studies of poor compliance with hand hygiene policies and glove use indicate a greater likelihood that HCWs will transmit MDROs to other patients. Thus, strategies to increase and monitor adherence to policies are important components of MDRO control programs.21

Transmission-based precautions

Airborne precautions are designed to reduce the risk of airborne transmission of infectious agents. Airborne transmission occurs with dissemination of either airborne droplet nuclei (5 μm or smaller in size of evaporated droplets that may remain suspended in the air for long periods of time) or dust particles that contain the infectious agent. Microorganisms carried in this manner can be dispersed widely by air currents and may become inhaled by or deposited on a susceptible host within the same room or over a longer distance from the source patient, depending on environmental factors; therefore negative-pressure isolation rooms are necessary for these patients. If such a room is not available, the patient should be given a mask to wear and should be segregated away from other patients. Prompt transfer of such patients to negative-pressure isolation rooms should be undertaken to minimize the risk of transmission. During transport, the patient should be masked. Personnel who transport the patient should not be masked. Examples of diseases that require airborne precautions include pulmonary tuberculosis, chickenpox, and disseminated zoster (shingles). Personnel who care for patients in airborne precautions must wear respiratory protection (N95 respirator) when entering the room of a patient with known or suspected infectious pulmonary tuberculosis.22,23 Susceptible persons should not enter the room of patients known or suspected to have measles (rubeola) or varicella (chickenpox) if other immune caregivers are available. If susceptible persons must enter the room of a patient known or suspected to have measles (rubeola) or varicella, they should wear respiratory protection (N95 respirator).23 Persons who are immune to measles or varicella need not wear respiratory protection.

Droplet precautions are designed to reduce the risk of droplet transmission of infectious agents. Droplet transmission involves contact of the conjunctivae or the mucous membranes of the nose or mouth of a susceptible person with large-particle droplets (larger than 5 μm) that contain microorganisms generated from an infected person. Droplets are generated from the source person, primarily during coughing, sneezing, or talking, and while performing certain procedures such as suctioning and bronchoscopy. Transmission via large-particle droplets necessitates close contact because droplets do not remain suspended in the air and generally travel only short distances, usually 3 feet or less, through the air. Because droplets do not remain suspended in the air, a negative-pressure room is not needed to prevent droplet transmission. HCWs should wear gowns, gloves, masks, and eye protection when within 3 feet of an infected patient. Because the environment can play a role in harboring contamination, prompt cleaning of visible contamination should be performed. In addition, multiple-patient care items (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, stethoscopes) should be disinfected before use on another patient. Hands can become contaminated through holes in gloves or during removal of PPE and therefore should be promptly washed after patient care and removal of PPE. During patient transportation, patient dispersal of droplets is minimized by the patient wear a mask.

A synopsis of the types of precautions and the patients who need the precautions is listed in the reference 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings.19 Although prospective identification of all patients who need these enhanced precautions is not possible, certain clinical syndromes and conditions carry a sufficiently high risk to warrant the empiric addition of enhanced precautions while a more definitive diagnosis is pursued. A listing of such conditions and the recommended precautions in addition to Standard Precautions is beyond the scope of this chapter, but can be referred to in the 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions.

Prevention of health care–associated infections

Currently, between 5% and 10% of patients admitted to acute care hospitals acquire one or more infections, and the risks have steadily increased during recent decades. These adverse events affect approximately 2 million patients each year in the United States, result in approximately 90,000 deaths, and add an estimated $4.5 to $5.7 billion per year to the costs of patient care.24 These infections are referred to as nosocomial infections or as health care–associated infections (the more recent terminology).

One area of surgical patient quality improvement in which perianesthesia nurses can play a significantly active role is the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP), originated by The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). This project is a national quality partnership of organizations focused on improvement of surgical care with significant reduction in surgical complications. Partners in SCIP believe that a meaningful reduction in surgical complications depends on surgeons, anesthesia providers, nurses, pharmacists, infection control professionals, and hospital executives working together to intensify their commitment to making surgical care improvement a priority.25 SCIP has identified seven processes or outcome measures related to infection prevention. They are listed in Box 5-1.

BOX 5-1 SCIP Process Measures for Prevention of Infection

SCIP INF 1: Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hour before surgical incision.

SCIP INF 2: Prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients.

SCIP INF 4: Patients for cardiac surgery with controlled, 6:00 am postoperative serum glucose.

SCIP INF 6: Surgery patients with appropriate hair removal.

SCIP INF 9: Urinary catheter removed on postoperative day 1 or 2 with day of surgery being day 0.

From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Hospital quality initiatives, process of care measures, available at www.cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/18_HospitalProcessOfCareMeasures.asp. Accessed September 21, 2011; TMF Health Quality Institute: SCIP quality indicators, available at http://hospitals.tmf.org/SCIP/SCIPQualityIndicators/tabid/678/Default.aspx. Accessed September 21, 2011; The Joint Commission: Specifications manual for national hospital inpatient quality measures, available at www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures/. Accessed September 21, 2011.INF, Measure related to infection; SCIP, Surgical Care Improvement Project.

The CDC estimates that approximately 500,000 SSIs occur annually in the United States.26 Patients who have SSIs are up to 60% more likely to spend time in an ICU, are fivefold more likely to be readmitted to the hospital, and have twice the mortality rate compared with patients without an SSI.27 A targeted process within the SCIP initiative to reduce SSIs is with the appropriate antimicrobial prophylaxis administration process because, despite evidence of effectiveness of antimicrobials to prevent SSIs, previous studies have shown inappropriate timing, selection, and excess duration of administration of antimicrobial prophylaxis. The SCIP measures are: (1) the proportion of patients who have parenteral antimicrobial prophylaxis initiated within 1 hour before the surgical incision; (2) the proportion of patients who are provided a prophylactic antimicrobial agent that is consistent with currently published guidelines; and (3) the proportion of patients whose prophylactic antimicrobial therapy is discontinued within 24 hours after the end of surgery.28

An additional measure gaining momentum in the surgical population because of the SCIP initiative is glucose control. Currently, the measures are limited to specific patient populations undergoing surgery, consistent with evidence-based medicine. The fourth SCIP CMS infection indicator addresses patients for cardiac surgery and the postoperative serum glucose. This recommendation was in part the result of studies such as Latham and colleagues,29 who concluded that diabetes (odds ratio [OR], 2.76; p < 0.001) and postoperative hyperglycemia (OR, 2.02; p = 0.007) were independently associated with development of SSIs. Former SCIP CMS infection indicator number 7 has been changed to SCIP indicator number 10. It is based on a study by Kurz and colleagues,30 who reported SSIs in 18 of 96 patients undergoing colorectal surgery who were hypothermic (19%), but in only 6 of 104 patients who were normothermic (6%; p = 0.009).30

Another SCIP process targeting SSI reduction is the issue of appropriate hair removal at the surgical site. The CDC Surgical Site Infection Prevention Guidelines state that preoperative shaving of the surgical site the night before an operation is associated with a significantly higher SSI risk than either the use of depilatory agents or no hair removal.31–36 Shaving immediately before the operation compared with shaving within 24 hours before surgery was associated with decreased SSI rates (3.1% versus 7.1%); if shaving was performed more than 24 hours before the operation, the SSI rate exceeded 20%.33 In addition to when the hair is removed, how it is removed is important as well. In one study, SSI rates were 5.6% in patients who had hair removed with razor shave compared with a 0.6% rate among those who had hair removed with depilatory or who had no hair removed.33 The increased SSI risk associated with shaving has been attributed to microscopic cuts in the skin that later serve as foci for bacterial multiplication. On the basis of the data, the SCIP recommendation is to avoid shaving surgical sites and to use clippers only if hair removal is necessary immediately before surgery.

The role of the perianesthesia nurse relative to the SCIP initiative varies because of institutional differences in ordering and administration of surgical prophylaxis, glucose control, maintenance of normothermia, and surgical site hair removal. Nonetheless, active collaboration with the initiative is essential for optimal outcomes.

Another recommendation from the CDC Surgical Site Infection Prevention Guidelines relates to a patient’s skin hygiene before surgery. A preoperative antiseptic shower or bath decreases skin microbial colony counts. In a study of more than 700 patients who received two preoperative antiseptic showers, chlorhexidine reduced bacterial colony counts ninefold (from 2.83 to 0.3) compared with other products.37 Although other studies corroborate these findings,38,39 a Cochrane Review found no added benefit of CHG over other antimicrobial soaps.40 CHG-containing products need several applications to attain maximal antimicrobial benefit; therefore repeated antiseptic showers are usually indicated.39 Although preoperative showers reduce the skin’s microbial colony counts, they have not definitively been shown to reduce SSI rates.41 However, from a basic hygiene perspective, a patient’s skin should be as clean as possible before surgery. Products are currently available that allow for quick and easy skin cleansing in the perioperative setting. They are CHG based and waterless.

Intravascular devices are regularly inserted into patients in the perianesthesia setting. Care must be taken during insertion and line management to prevent bloodstream infections. The incidence rate of central line–associated bloodstream infection (CLA-BSI) varies considerably by type of catheter, frequency of catheter manipulation, and patient-related factors (e.g., underlying disease, acuity of illness). Peripheral venous catheters are the devices most frequently used for vascular access. Although the incidence rate of local infections or bloodstream infections (BSIs) associated with peripheral venous catheters is usually low, serious infectious complications produce considerable annual morbidity rates because of the frequency with which such catheters are used. However, most serious catheter-related infections are associated with central line venous catheters. A total of 250,000 cases of CLA-BSIs has been estimated to occur annually.42 The attributable mortality rate is an estimated 12% to 25% for each infection, and the marginal cost to the health care system is $25,000 per episode.42

In the perianesthesia setting, the biggest effect on prevention of CLA-BSI is control of the insertion process and adherence to aseptic technique. Best practice recommendations for skin preparation include use of an appropriate antiseptic before catheter insertion and during dressing changes. A 2% chlorhexidine-based preparation is preferred, but tincture of iodine, an iodophor, or 70% alcohol can also be used.43–46

The level of barrier precautions needed to prevent infection during insertion of central lines is more stringent then what is required for peripheral venous or arterial catheters. Maximal sterile barrier precautions (e.g., cap, mask, sterile gown, sterile gloves, and large sterile drape) during the insertion of central lines substantially reduces the incidence rate of CLA-BSI compared with Standard Precautions (e.g., sterile gloves, small drapes).47,48 To further reduce the likelihood of contamination of the line, injection ports should be cleaned with 70% alcohol or an iodophor before the system is accessed, and all stopcocks should be capped when not in use.49–51

Occupational health

Recommendations for minimization of exposures include taking care to prevent injuries: with use of needles, scalpels, and other sharp instruments or devices; with handling of sharp instruments after procedures; with cleaning of used instruments; and with disposal of used needles. Used needles should never be recapped or otherwise manipulated with both hands or with any other technique that involves directing the point of a needle toward any part of the body used. Instead, either a one-handed scoop technique or a mechanical device designed for holding the needle sheath should be used. Used needles from disposable syringes should not be removed by hand and should not be bent, broken, or otherwise manipulated by hand. Used disposable syringes and needles, scalpel blades, and other sharp items should be disposed in appropriate puncture-resistant containers that are located as close as practical to the area in which the items were used, and reusable syringes and needles should be placed in a puncture-resistant container for transport to the reprocessing area. Certain states in the United States (currently Michigan and Florida) require sharps waste containing residual medication to be managed in a separate sharps container to prevent pharmaceuticals from entering the routine waste stream.

Perianesthesia nurses should protect themselves against infection from HBV with vaccination with the HBV vaccine, unless contraindicated for medical reasons. With proper administration, the vaccine is approximately 90% (80% to 95%) effective in prevention of infection in susceptible vaccine recipients. Immunity produced by this vaccination possibly will decrease with time and boosters will have to be given to ensure protection.52 Per OSHA standards, this vaccine must be made available at no cost to the employee and must be accompanied by the necessary training requirements.

In addition to the HBV vaccine, additional vaccines are recommended to ensure that personnel are immune to vaccine-preventable diseases. Optimal use of vaccines can prevent transmission of diseases and eliminate unnecessary work restriction. Prevention of illness through comprehensive personnel immunization programs is far more cost effective than case management and outbreak control. Mandatory immunization programs, which include both newly hired and currently employed persons, are more effective than voluntary programs in ensuring that susceptible persons are vaccinated.53 National guidelines for immunization of and postexposure prophylaxis for health care personnel are provided by the U.S. Public Health Service’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.54

Safe injection practices

Per the CDC One and Only campaign, since 1999 more than 125,000 U.S. patients have been potentially exposed to a bloodborne pathogen, such as HIV, HBV, or HCV because of an HCW’s or facility’s unsafe injection practice.55 A review to quantify the issue in nonhospital settings (e.g., nursing homes, free standing infusion centers, pain clinics) identified 33 outbreaks of HBV or HCV that were epidemiologically linked to lapses in infection control practices, resulting in 448 patients acquiring a bloodborne pathogen infection. Eighteen of these outbreaks were related to syringe re-use or mishandling of medication vials.56 See Box 5-2 for some basic steps that should be applied to every patient to prevent the transmission of bloodborne pathogens.

BOX 5-2 Steps to Prevent Transmission of a Blood-Borne Pathogen

Do

• Use single-dose vials for parenteral medications whenever possible.

• Use a sterile device to access MDVs and avoid touching the access diaphragm.

• Keep MDVs away from the immediate patient treatment area to prevent inadvertent contamination.

• Always wipe the top of medication vials with 70% isopropyl alcohol before accessing, even if a new vial.

• Discard any vial if the sterility is compromised.

• Do not “double-dip” into MDVs with a used needle and/or syringe. If double-dipping does occur, then discard the MDVs after use on that single patient.

• Use fluid infusion and administration sets (i.e., IV bags, tubings, connections) for one patient only and dispose of them promptly when no longer in use.

Summary

Providing care in a perianesthesia unit is not without infectious risks for patients and the HCW in the environment. Adherence to published guidelines and institutional policies for minimization of infectious risks is paramount for optimal patient and employee outcomes. Simple tasks such as hand washing can significantly reduce the incidence rate of health care–associated infections and reduce the transmission of disease. Additional measures to ensure a safe and clean environment and equipment further lower the risks. Lastly, the perianesthesia nursing team can play a significant role in the quality improvement process of the surgical patient and can greatly affect outcomes that benefit the patient and the institution.

1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration: 29CFRPart 1910:1030: Occupational exposure to bloodbornepathogens: final rule, federal register. Washington, DC: OSHA; 1991.

2. AIA Facilities Guidelines Institute: Guidelines for design and construction of healthcare facilities. Washington, DC: AIA; 2010.

3. Potter P, Semmelweis I. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:368. available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/content/7/2/pdfs/v7-n2.pdf Accessed September 20, 2011

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings. MMWR. 2002;51(RR-16).

5. Pittet D, et al. Members of the infection control program: compliance with handwashing in a teaching hospital. Ann Intern Med.1999;130:26–130.

6. Larson E, Killien M. Factors influencing handwashing behavior of patient care personnel. Am J Infect Control. 1982;10:93–99.

7. Conly JM, et al. Handwashing practices in an intensive care unit: the effects of an educational program and its relationship to infection rates. Am J Infect Control.1989;17:330–339.

8. Dubbert PM, et al. Increasing ICU staff handwashing: effects of education and group feedback. Infect Control Hosp Epid.1990;11:91–193.

9. Larson E, Kretzer EK. Compliance with handwashing and barrier precautions. J Hosp Infect. 1995;30:88–106. (suppl)

10. Sproat LJ, Inglis TJJ. A multicentre survey of hand hygiene practice in intensive care units. J Hosp Infect. 1994;26:137–148.

11. Kretzer EK, Larson EL. Behavioral interventions to improve infection control practices. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26:245–253.

12. Tupker RA. Detergents and cleansers. In: van der Valk PGM, Maibach HI. The irritant contact dermatitis syndrome. New York: CRC Press, 1996.

13. Garner JS, Simmons BP. Guideline for isolation precautions in hospitals. Infect Control. 1983;4(suppl 4):245–325.

14. McFarland LV, et al. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:204–210.

15. Pittet D, et al. Bacterial contamination of the hands of hospital staff during routine patient care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:821–826.

16. Tenorio AR, et al. Effectiveness of gloves in the prevention of hand carriage of vancomycin-resistant. Enterococcus species by health care workers after patient care, Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:826–829.

17. Ehrenkranz NJ, Alfonso BC. Failure of bland soap handwash to prevent hand transfer of patient bacteria to urethral catheters. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1991;12:654–662.

18. Kjrlen H, Andersen BM. Handwashing and disinfection of heavily contaminated hands—effective or ineffective. J Hosp Infect. 1992;21:61–71.

19. Siegel JD, et al. and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee: 2007 Guideline for isolation precautionspreventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007IP/2007isolationPrecautions.html, September 12, 2011. Accessed

20. Seigel JD, et al. and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee: Management of multidrug resistant organisms in healthcare settings 2006. available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/guidelines/MDROGuideline2006.pdf, September 26, 2011. Accessed

21. Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Reduce healthcare-associated infections. available at: http://www.ihi.org/explore/HAI/Pages/default.aspx, March, 2007. accessed

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Guidelines for preventing the transmission of tuberculosis in health-care facilities. MMWR.1994;43(RR-13):1–132.

23. Department of Health and Human Services Department of Labor: Respiratory protective devices final rules and notice. Federal Register.1995;60(110):30336–30402.

24. Burke JP. Infection control—a problem for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:651–656.

25. MedQIC. Surgical care improvement project. available at http://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures, September 20, 2011. Accessed

26. Wong ES. Surgical site infection. Mayhall DG, ed. Hospital epidemiology and infection control, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

27. Kirkland KB, et al. The impact of surgical site infections in the 1990s – attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:725–730.

28. Bratzler DW, Houck PM. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Clin Infect Dis.2004;38:1706–1715.

29. Latham R, et al. The association of diabetes and glucose control with surgical-site infections among cardiothoracic surgery patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(10):604–606.

30. Kurz A, et al. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1209–1215.

31. Cruse PJ, Foord R. The epidemiology of wound infection: a 10-year prospective study of 62,939 wounds. Surg Clin North Am.1980;1(60):27–40.

32. Mishriki SF, et al. Factors affecting the incidence of postoperative wound infection. J Hosp Infect. 1990;16:223–230.

33. Seropian R, Reynolds BM. Wound infections after preoperative depilatory versus razor preparation. Am J Surg. 1971;121:251–254.

34. Hamilton HW, et al. Preoperative hair removal. Can J Surg. 1977;20:269–271.

35. Olson MM, et al. Preoperative hair removal with clippers does not increase infection rate in clean surgical wounds. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;162:181–182.

36. Mehta G, et al. Computer assisted analysis of wound infection in neurosurgery. J Hosp Infect. 1988;11:244–252.

37. Garibaldi RA. Prevention of intraoperative wound contamination with chlorhexidine shower and scrub. J Hosp Infect. 1988;11(Suppl B):5–9.

38. Paulson DS. Efficacy evaluation of a 4% chlorhexidine gluconate as a full-body shower wash. Am J Infect Control. 1993;21(4):205–209.

39. Hayek LJ, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of the effect of two preoperative baths or showers with chlorhexidine detergent on postoperative baths or showers with chlorhexidine detergent on postoperative wound infection rates. J Hosp Infect. 1987;10:165–172.

40. Webster J, Osborne S. Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2, 2006. (CD004985)

41. The European Working Party on Control of Hospital Infections: A comparison of the effects of preoperative whole-body bathing with detergent alone and with detergent containing chlorhexidine gluconate on the frequency of wound infections after clean surgery. J Hosp Infect.1988;11:310–320.

42. Kluger DM, Maki DG. The relative risk of intravascular device related bloodstream infections in adults. San Francisco: Proceeding of the Abstracts of the 39th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, American Society for Microbiology; 1999. abstract]

43. Maki DG, et al. Prospective randomised trial of povidone-iodine, alcohol, and chlorhexidine for prevention of infection associated with central venous and arterial catheters. Lancet. 1991;338:339–343.

44. Garland JS, et al. Comparison of 10% povidone-iodine and 0.5% chlorhexidine gluconate for the prevention of peripheral intravenous catheter colonization in neonates: a prospective trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J.1995;14:510–516.

45. Little JR, et al. A randomized trial of povidone-iodine compared with iodine tincture for venipuncture site disinfection: effects on rates of blood culture contamination. Am J Med.1999;107:119–125.

46. Mimoz O, et al. Prospective, randomized trial of two antiseptic solutions for prevention of central venous or arterial catheter colonization and infection in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1818–1823.

47. Mermel LA, et al. The pathogenesis and epidemiology of catheter-related infection with pulmonary artery Swan-Ganz catheters: a prospective study utilizing molecular subtyping. Am J Med.1991;91(Supp 2):S197–S205.

48. Raad II, et al. Prevention of central venous catheter-related infections by using maximal sterile barrier precautions during insertion. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15:231–238.

49. Luebke MA, et al. Comparison of the microbial barrier properties of a needleless and a conventional needle-based intravenous access system. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26:437–441.

50. Salzman MB, et al. Use of disinfectants to reduce microbial contamination of hubs of vascular catheters. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:475–479.

51. Plott RT, et al. Iatrogenic contamination of multidose vials in simulated use: a reassessment of current patient injection technique. Arch Dermatol.1990;126:1441–1444.

52. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. CPL 2-2OSHA instruction: subject: hepatitis B risks in the health care system. Washington, DC: Office of Occupational Medicine; 1983.

53. Bolyard EA, et al. The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee: Guideline for infection control in health care personnel. Am J Infect Control.1998;26(3):289–354.

54. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (AICP): Immunization of health-care workers recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). MMWR.1997;46(RR-18):1–42.

55. Center for Disease Control and Prevention: CDC’s Role in Safe Injection Practices. available at: http://www.cdc.gov/injectionsafety/, 2011. Accessed September 15

56. Thompson ND, et al. Nonhospital health care-associated hepatitis B and C virus transmission: United States, 1998-2008. Ann Intern Med.2009;150:33–39.

Resources

Allen G. Infection prevention in the perioperative setting: zero tolerance for infections, an issue of perioperative nursing clinics. St. Louis: Saunders; 2010.

Hooper VD, et al. ASPAN’s evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the promotion of perioperative normothermia:Second edition. J Perianesth Nurs. 2010;25:346–365.

Block S. Disinfection, sterilization and preservation, ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001.

Jensen PA, et al. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings. MMWR. 2005;54(RR-17):1–141.

Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act: public law 106–430, 106th Congress. available at: http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/bloodbornepathogens/index.html, September 12, 2011. Accessed

Kaye K. Infection prevention and control in the hospital, an issue of infectious disease clinics. St. Louis: Saunders; 2011.

Kerr CM, Savage GT. Managing exposure to tuberculosis in the PACU: CDC guidelines and cost analysis. J Perianesth Nurs.1996;11(3):143–146.

Mangram AJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):250–278.

Sullivan EE. The use of contact and airborne precautions in the perianesthesia setting. J Perianesth Nurs. 2002;17(3):190–192.

Sullivan EE. Off with her nails. J Perianesth Nurs. 2003;18(6):417–418.

Yokoe DS, et al. A compendium of strategies to prevent healthcare-associated infections in acute care hospitals. Infect Cont and Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(Suppl 1):S12–S21.