Infection Control

1. Define and compare health care–associated infections and community-acquired infections.

2. List three factors determining the likelihood that a given patient would acquire a health care–associated infection.

3. State the most common types of health care–associated infections, and identify the risk factors that predispose patients to acquire each infection.

4. Explain the emergence of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms and their impact on health care.

5. Describe hospital infection control programs, and outline the structure and responsibilities of the infection control committee in a medical facility.

6. Identify means of transmission for microorganisms within a health care facility.

7. Interpret the role of the microbiology laboratory in an infectious outbreak.

8. Compare the two major ways to characterize strains involved in an outbreak.

9. Discuss techniques for isolation precautions used to prevent the spread of health care–associated infections.

10. Identify potential useful applications for surveillance cultures.

Emergence of Antibiotic-Resistant Microorganisms

The organisms that cause HAIs have changed over the years because of selective pressures from the use (and overuse) of antibiotics (see Chapter 11). Risk factors for the acquisition of highly resistant organisms include prolonged hospitalization and prior treatment with antibiotics. In the pre-antibiotic era, most HAIs were caused by S. pneumoniae and group A Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes). In the 1940s and 1950s, with the advent of treatment of patients with penicillin and sulfonamides, resistant strains of S. aureus appeared. Then, in the 1970s, treatment of patients with narrow-spectrum cephalosporins and aminoglycosides led to the emergence of resistant aerobic gram-negative rods, such as Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Pseudomonas. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the use of more potent cephalosporins played a role in the emergence of antibiotic-resistant, coagulase-negative staphylococci, enterococci, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), and Candida spp. The 1990s witnessed the emergence of beta-lactamase–producing, high-level gentamicin-resistant, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). The twenty-first century has seen the emergence of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA).

Hospital Infection Control Programs

Microorganisms are spread in hospitals through several modes:

• Direct contact—for example, in contaminated food or intravenous solutions

• Indirect contact, for example, from patient to patient on the hands of health care workers (MRSA, rotavirus)

• Droplet contact—for example, inhalation of droplets (>5 µm in diameter) that cannot travel more than 3 feet (pertussis)

• Airborne contact—for example, inhalation of droplets (>5 µm) that can travel large distances on air currents (tuberculosis)

• Vector-borne contact—for example, disease spread by vectors, such as mosquitoes (malaria) or rats (rat-bite fever); this mode of transmission is rare in hospitals in developed countries

Once the reservoir is known, the infection control practitioner can implement control measures, such as reeducation regarding hand washing (in the case of spread by health care workers) or hyperchlorination of cooling towers in the case of legionellosis.

Role of the Microbiology Laboratory

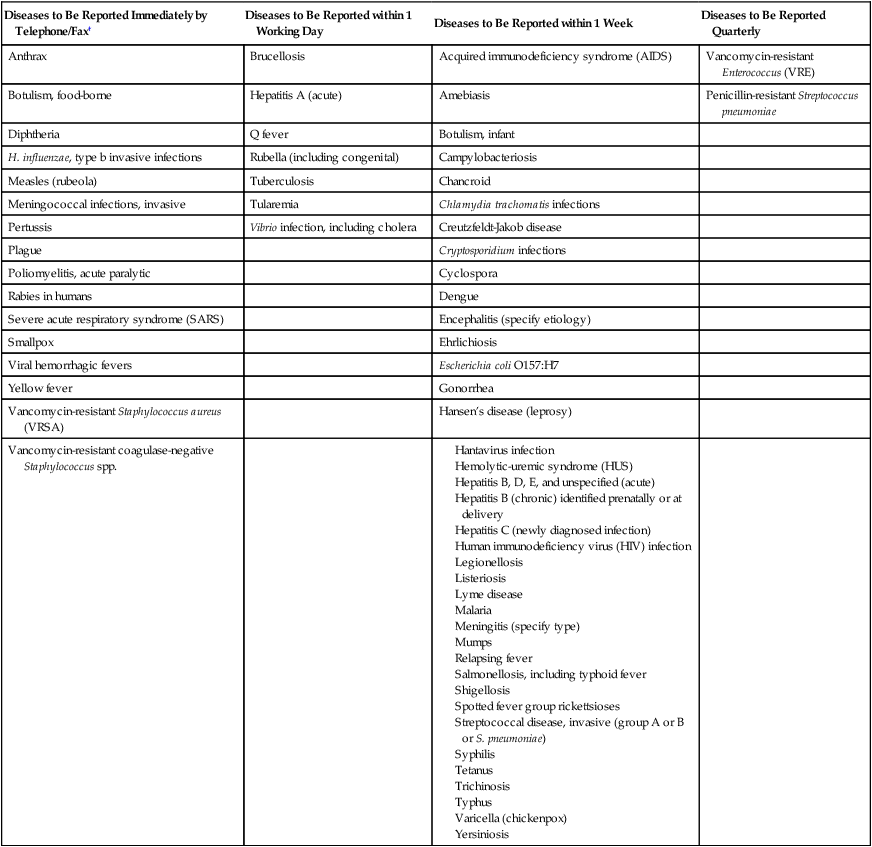

The microbiology laboratory supplies the data on organism identification and antimicrobial susceptibility profile that the infection control practitioner reviews daily for evidence of HAI. Thus, the laboratory personnel must be able to detect potential microbial pathogens and then accurately identify them to species level and perform appropriate susceptibility testing. The microbiology laboratory staff should also monitor multidrug-resistant organisms by tabulating data on antimicrobial susceptibilities of common isolates and studying trends indicating emerging resistance. Significant findings should be immediately reported to the infection control practitioner. If an outbreak is suspected, the laboratory works in tandem with the infection control committee by (1) saving all isolates, (2) culturing possible reservoirs (patients, personnel, or the environment), and (3) performing typing of strains to establish relatedness between isolates of the same species. Microbiology laboratories are also obligated by law to report certain isolates or syndromes to public health authorities. For example, Table 79-1 lists organisms to be reported to state health authorities in Texas. Other states have similar criteria.

TABLE 79-1

Examples of Notifiable Infectious Conditions in Texas*

| Diseases to Be Reported Immediately by Telephone/Fax† | Diseases to Be Reported within 1 Working Day | Diseases to Be Reported within 1 Week | Diseases to Be Reported Quarterly |

| Anthrax | Brucellosis | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) | Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) |

| Botulism, food-borne | Hepatitis A (acute) | Amebiasis | Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Diphtheria | Q fever | Botulism, infant | |

| H. influenzae, type b invasive infections | Rubella (including congenital) | Campylobacteriosis | |

| Measles (rubeola) | Tuberculosis | Chancroid | |

| Meningococcal infections, invasive | Tularemia | Chlamydia trachomatis infections | |

| Pertussis | Vibrio infection, including cholera | Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease | |

| Plague | Cryptosporidium infections | ||

| Poliomyelitis, acute paralytic | Cyclospora | ||

| Rabies in humans | Dengue | ||

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | Encephalitis (specify etiology) | ||

| Smallpox | Ehrlichiosis | ||

| Viral hemorrhagic fevers | Escherichia coli O157:H7 | ||

| Yellow fever | Gonorrhea | ||

| Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) | Hansen’s disease (leprosy) | ||

| Vancomycin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. |

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) Hepatitis B, D, E, and unspecified (acute) Hepatitis B (chronic) identified prenatally or at delivery Hepatitis C (newly diagnosed infection) Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection Salmonellosis, including typhoid fever Spotted fever group rickettsioses Streptococcal disease, invasive (group A or B or S. pneumoniae) |

*In addition to individual case reports, any outbreak, exotic disease, or unusual group expression of disease that may be of public health concern should be reported by the most expeditious means. This list is not all-inclusive and is updated annually.

†Report even if only suspected; waiting for confirmation may hamper public health intervention activities.

Characterizing Strains Involved in an Outbreak

Genotypic, or molecular, methods have largely replaced phenotypic methods as a means of confirming the relatedness of strains involved in an outbreak. Plasmid analysis and restriction endonuclease analysis of chromosomal DNA are widely used. Plasmids are extrachromosomal pieces of genetic material (nucleic acids) that self-replicate (reproduce). Plasmids may be transferred from one bacterial cell to another by conjugation or transduction (see Chapter 2). Plasmid analysis has often been used to explain the occurrence of unusual or multiple-antibiotic resistance patterns. It has been shown that plasmids or R factors (resistance genes carried on plasmids) can cause outbreaks when a specific plasmid is transmitted from one genus of bacteria to another. Plasmid profiles, patterns created when plasmids are separated based on molecular weight by agarose gel electrophoresis, can also be used to characterize the similarity of bacterial strains. Relatedness of strains is based on the number and size of plasmids, with strains from identical sources showing identical plasmid profiles. Plasmids themselves or chromosomal DNA may also be typed by means of restriction endonuclease digestion patterns. Restriction enzymes recognize specific nucleotide sequences in DNA and produce double-stranded cleavages that break the DNA into smaller fragments. The fragments of various sizes are separated using gel electrophoresis based on molecular weight. The specific recognition sequence and cleavage site have been defined for a great many of these enzymes.

Other molecular methods, such as PCR (polymerase chain reaction), are used in conjunction with these methods for strain typing. Molecular methods are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.

Preventing HAI

In 1996, the CDC developed a new system of standard precautions synthesizing the features of universal precautions (described in Chapter 4) and body substance isolation. Standard precautions are used in the care of all patients and apply to blood; all body fluids, secretions, and excretions except sweat, regardless of whether they contain visible blood; nonintact skin; and mucous membranes.

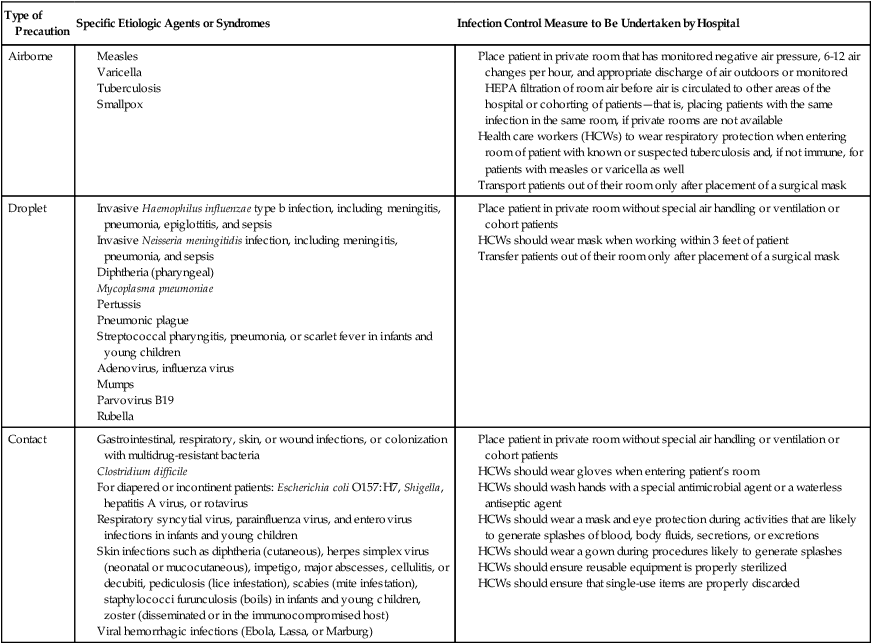

In addition, transmission-based precautions are used for patients known (or suspected) to be infected with pathogens spread by airborne or droplet transmission or by contact with dry skin or fomites. Box 79-1 lists infection control measures for standard precautions. Table 79-2 lists the infectious agents or syndromes along with the respective infection control measures for each transmission-based precaution. Many infection control practitioners find these guidelines a lot less cumbersome to implement than the old category- and disease-specific measures. Hospitals, however, may modify these guidelines to fit their individual situations as long as their number of HAIs remains low.

TABLE 79-2

Transmission-Based Precautions

| Type of Precaution | Specific Etiologic Agents or Syndromes | Infection Control Measure to Be Undertaken by Hospital |

| Airborne |

Place patient in private room that has monitored negative air pressure, 6-12 air changes per hour, and appropriate discharge of air outdoors or monitored HEPA filtration of room air before air is circulated to other areas of the hospital or cohorting of patients—that is, placing patients with the same infection in the same room, if private rooms are not available

Health care workers (HCWs) to wear respiratory protection when entering room of patient with known or suspected tuberculosis and, if not immune, for patients with measles or varicella as well

Transport patients out of their room only after placement of a surgical mask

Gastrointestinal, respiratory, skin, or wound infections, or colonization with multidrug-resistant bacteria

For diapered or incontinent patients: Escherichia coli O157:H7, Shigella, hepatitis A virus, or rotavirus

Respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, and enterovirus infections in infants and young children

Skin infections such as diphtheria (cutaneous), herpes simplex virus (neonatal or mucocutaneous), impetigo, major abscesses, cellulitis, or decubiti, pediculosis (lice infestation), scabies (mite infestation), staphylococci furunculosis (boils) in infants and young children, zoster (disseminated or in the immunocompromised host)

Place patient in private room without special air handling or ventilation or cohort patients

HCWs should wear gloves when entering patient’s room

HCWs should wash hands with a special antimicrobial agent or a waterless antiseptic agent

HCWs should wear a mask and eye protection during activities that are likely to generate splashes of blood, body fluids, secretions, or excretions

HCWs should wear a gown during procedures likely to generate splashes

HCWs should ensure reusable equipment is properly sterilized

HCWs should ensure that single-use items are properly discarded

Modified from Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), 2007.