Infection and Inflammation

Pharyngotonsillitis and Peritonsillar Abscess

Overview: The pharyngeal wall and tonsillar fossa are common locations of infection, particularly in children. Acute pharyngitis, which is diagnosed more than 7 million times per year, does not require imaging for diagnosis. However, when a peritonsillar abscess is suspected, imaging is indicated for diagnosis and surgical management in some cases.1

Etiology: Most pharyngitis cases are self-limited viral infections. Accounting for up to 30% of cases, acute bacterial pharyngitis is most often secondary to group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GAS).1 Children with pharyngitis present with sore throat, fever, and odynophagia. Lack of improvement with antibiotics suggests the possibility of a peritonsillar abscess. The peritonsillar space is the most common abscess location in the neck.2

Imaging: Routine pharyngitis and tonsillitis do not require imaging.1 However, in children suspected of having complications, contrast-enhanced CT is performed.3 Findings of uncomplicated tonsillitis include unilateral or bilateral enlarged, enhancing tonsils with inflammatory stranding of the parapharyngeal fat. Abscess formation is suggested by a central hypodense fluid collection, with peripheral enhancement within or immediately adjacent to an enlarged tonsil (Fig. 15-1).3 Follow-up imaging is only performed in children with complications and persistent clinical symptoms.1,2

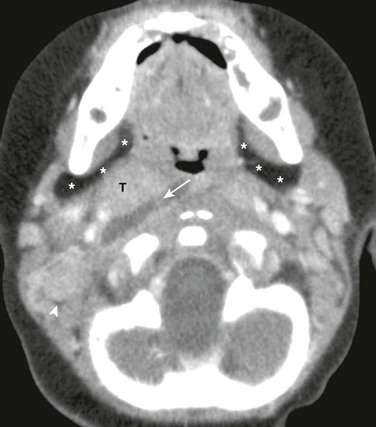

Figure 15-1 Parapharyngeal abscess in a 7-month-old male with fever and difficulty swallowing.

Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography image of the suprahyoid neck just below the skull base shows a well-defined, right-sided, low-attenuation fluid collection (arrow) adjacent to the tonsils (T). The right parapharyngeal fat (asterisks) and carotid spaces are displaced laterally. Also, note right-sided prominent lymph nodes (arrowhead) and normal left parapharyngeal fat (asterisks).

Treatment: Viral tonsillitis is self-limiting and requires only supportive treatment, but GAS infections, confirmed by a rapid antigen test or throat culture, are initially treated with antibiotics. Children with recurrent tonsillitis are candidates for tonsillectomy.4 Those with focal fluid collections identified by CT may require surgical aspiration and drainage. Tonsillar and peritonsillar infections have an excellent prognosis.1,2

Lemierre Syndrome

Overview: Also known as suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, Lemierre syndrome is an uncommon complication of oropharyngeal infection occurring most often in previously healthy teenagers.5 Although rare, complications, including septic dissemination with abscess formation in other parts of the body (most commonly in the lungs), osteomyelitis, and arterial vasospasm or occlusion leading to infarction, may be severe.6

Etiology: Lemierre syndrome is caused by Fusobacterium infection, an anaerobic gram-negative bacterium found in normal oral flora.6 Fusobacterium necrophorum is the most common species, with F. nucleatum, F. mortiferum, or F. varium occurring less often. Recognition is important because of the high rate of morbidity and mortality associated with this syndrome.5,7 Infection spreads from the peritonsillar space into the internal jugular vein, causing thrombus formation.5 From the jugular vein, septic emboli may seed other organs such as the lungs and brain, leading to abscess formation.7,8 Spread to adjacent neck spaces, including the retropharyngeal space and osseous structures, may occur, causing osteomyelitis. Patients present with a recent history of sore throat, tenderness, swelling of the lateral neck, and fever.5 With pulmonary involvement, tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxia may be present. Blood cultures are positive for the causative organism.9

Imaging: As with other head and neck infections, Fusobacterium infections present acutely, requiring rapid evaluation. Contrast-enhanced CT is the initial imaging modality of choice. CT findings include inflammatory changes that may involve various spaces of the neck and lack of enhancement within the jugular vein indicating thrombus.5 Inflammatory findings range from enhancing soft tissues of cellulitis to focal fluid collections indicating an abscess (Figs. 15-2 and 15-3). Chest CT may be concurrently performed if respiratory symptoms are present, and a search for osseous involvement is part of the CT evaluation. Color Doppler ultrasonography is useful to visualize and follow thrombophlebitis but is not reliably able to visualize deep neck infection as may occur with Lemierre syndrome.5,6 Acute neurologic symptoms may be evaluated with CT or MRI, and both may be augmented by angiographic techniques as well.7

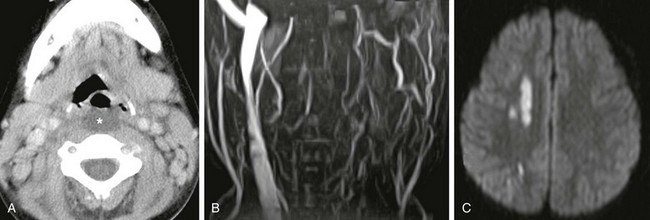

Figure 15-2 Lemierre syndrome (Fusobacterium necrophorum infection) complicated by stroke in a 6-year-old female presenting with fever, difficulty swallowing, and nuchal rigidity.

A, Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography image shows low-attenuation retropharyngeal fluid (asterisk). B, Magnetic resonance imaging 2 days later, performed because of acute left arm weakness, confirms lack of left internal jugular vein patency on magnetic resonance venogram. C, Diffusion-weighted image of the brain reveals multiple small foci of bright signal infarction secondary to emboli from thrombophlebitis, vasospasm, or both.

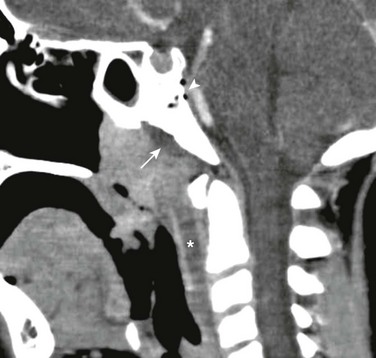

Figure 15-3 Lemierre syndrome (Fusobacterium necrophorum infection) complicated by osteomyelitis in a 9-year-old with fever, neck pain, and sore throat.

Sagittal reconstructed contrast enhanced computed tomography image demonstrates enlarged adenoids, a low-attenuation retropharyngeal fluid collection (asterisk), and a subperiosteal fluid collection along the ventral clivus (arrow). Air within and dorsal to the clivus due to osteomyelitis (arrowhead) is also seen. Venous occlusion was also present (not shown).

Treatment: High-dose intravenous antibiotics, including metronidazole, penicillin, and clindamycin, are the mainstay for treatment of Fusobacterium infection and have a high success rate. Anticoagulation therapy is used in up to 27% of patients, although its role is not completely clear.5 Follow-up imaging is performed in patients who do not defervesce as expected and those with complications that may require closer follow-up. Although the prognosis of Fusobacterium infections is good with prompt recognition and treatment, the rates of morbidity and mortality are higher than with other head and neck infections.2,9

Retropharyngeal Abscess

Overview: Retropharyngeal abscesses in children commonly result from suppurative lymphadenitis associated with tonsillitis, as well as with sinonasal and dental infections.10,11 Retropharyngeal abscess may rarely be caused by pharyngeal or esophageal perforation. The retropharyngeal space, the second most common location of abscess in the deep neck after the peritonsillar space, is a potential space that extends from the nasopharynx to the superior mediastinum.10 Abscesses extending below the T4 vertebra cause concern with regard to what is termed danger space infections, which have a high rate of morbidity. Other uncommon conditions that cause thickening of the retropharyngeal tissues include hemorrhage (especially in hemophilia), neuroblastoma, and rarely anterior myelomeningocele.

Etiology: Retropharyngeal abscesses are sequelae of GAS, but Staphylococcus aureus and infrequent anaerobes have also been reported as causative organisms.2,10 The most common presenting symptoms are fever, neck pain, dysphagia, palpable neck mass, and sore throat. Cervical lymphadenopathy and torticollis are often present.11

Imaging: Plain radiography, often ordered as the initial study to screen for large fluid collections, is otherwise limited in its ability to distinguish between cellulitis and abscess, both of which may cause convex abnormal thickening of the prevertebral soft tissues (>8 mm at C2).4 Anterior displacement of the pharynx, esophagus, larynx, trachea, or all of these is seen from C1 to C4 (Fig. 15-4). Grisel syndrome is inflammation-induced laxity of the atlantoaxial joint, which may result in atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation or other malalignment of C1 and C2. This self-limiting sequence of symptoms and signs disappears with resolution of the inflammatory process. Contrast-enhanced CT is the study of choice to further check for hypoattenuating, rim-enhancing abscess collections and to determine the need for surgical drainage.4,10 If an abscess is present, CT is able to define the extent of the collection, to check for mediastinal involvement, and to detect other complications that may occur with head and neck infections such as thrombophlebitis and osteomyelitis.4

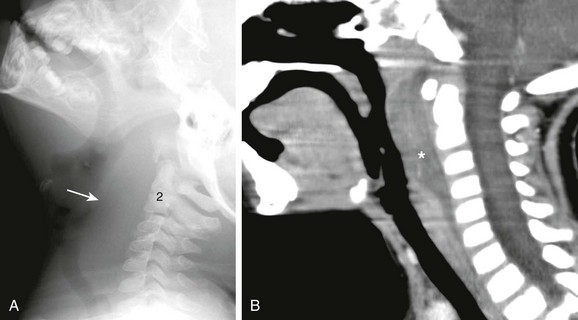

Figure 15-4 Retropharyngeal abscess in a 3-year-old female with sore throat and fever.

A, Lateral soft tissue neck radiograph reveals extensive soft tissue swelling displacing the airway anteriorly from the skull base to C6 (arrow). B, Sagittal reconstructed contrast-enhanced computed tomography confirms thickened, enhancing retropharyngeal soft tissues indicating cellulitis. Region of hypoattenuating fluid is concerning for retropharyngeal abscess (asterisk).

Cervical Lymphadenitis

Overview: Cervical lymphadenitis is a common pediatric disorder. Acute cases are often caused by viral or bacterial pathogens and in general respond well to supportive care and antibiotics, respectively.12 Imaging is only considered in subacute and chronic cases when no clinical improvement is seen with standard therapy or when distinguishing abscess from lymphadenitis and cellulitis is required.13

Etiology: Cervical lymphadenitis is usually secondary to spread of infection from a source in the head and neck such as the tonsils, pharynx, or teeth. Common presenting symptoms include tender focal neck swelling with palpable mass and fever.13 The most common cause of enlarged cervical lymph nodes in children is a self-limiting reactive hyperplasia as a result of viral infection.14 However, bacterial causes, including S. aureus and streptococcal species, may also occur and occasionally lead to nodal suppuration. Kawasaki disease can also present with acute cervical lymphadenitis, but other organ system features such as rash and fever for at least 5 days, are also present.13,15

Imaging: Inflamed lymph nodes are usually enlarged, measuring more than 1 cm in short axis. Necrotic or suppurative lymph nodes are characterized by a hypoechoic or hypodense center (Fig. 15-5).12 Infectious adenopathy is more common than malignant adenopathy; however, cross-sectional imaging such as ultrasonography, CT, and MRI cannot distinguish between them specifically.

Figure 15-5 Suppurative lymphadenitis in a 5-year-old female with neck swelling and redness.

Contrast enhanced computed tomography image reveals a group of enlarged nodes in the right posterior triangle with central hypoattenuating necrosis (arrow). Also note enlarged tonsils (T) in this child with recurrent tonsillitis.

Mycobacterial Lymphadenitis

Overview: Mycobacterial infection is an important cause of chronic cervical lymphadenitis. In the United States, 70% to 95% of cases of mycobacterial lymphadenitis are caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM).13 NTM lymphadenitis commonly affects children between 1 and 5 years of age.16 It is clinically important to differentiate tuberculous and nontuberculous causes, as they require different treatment measures.

Etiology: Cervical mycobacterial lymphadenitis may be caused by various species, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis, and M. avium-intracellulare. In children, the illness is often indolent and may be self-limiting. Patients commonly present with nodal enlargement that slowly develops over several weeks. A strongly positive tuberculin skin test suggests M. tuberculosis, whereas a weakly positive test suggests NTM.13 The term scrofula is used for tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis and is typically diagnosed with aspiration and culture.17

Imaging: On CT, classic M. tuberculosis lymphadenitis appears as a nodal mass with a thick enhancing rim and a low-density center representing necrosis.18 At later stages, areas of calcification may be present. Differential diagnoses include lymphoma and metastatic disease. MRI findings correlate with CT findings. The thick enhancing rim on CT appears as intermediate signal on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images. Central necrotic areas appear as hypointense on T1-weighted images and markedly hyperintense on T2-weighted images.18 Chest imaging can help evaluate for pulmonary involvement. Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of NTM shows low attenuation, necrotic, ring-enhancing lesions (Fig. 15-6).19 These lesions differ from other nodal infections in that little to no surrounding fat stranding is present. Unlike M. tuberculosis lymphadenitis, calcifications are uncommon in NTM infection.19

Figure 15-6 Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in a 10-year-old male with tender left neck swelling.

Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography image shows a cluster of enlarged nodes in the left neck containing low attenuation necrotic centers (arrow). Other sites of infection (not shown) in this child included hilar nodes and a rib.

Treatment: A 12- to 18-month course of multiple antituberculosis antibiotics such as isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, rifampin, and streptomycin is the preferred treatment for M. tuberculosis lymphadenitis.13 With this therapy, prognosis is excellent. NTM adenitis requires complete excision of the infected lymph node for optimal treatment and has a high cure rate.16

Cat Scratch Disease

Overview: Cat scratch disease is a granulomatous infection that is usually self-limiting, with 87% of cases being seen in patients younger than18 years.20 In addition to regional cervical lymphadenitis, disseminated disease can cause granulomas in the liver or spleen, osteomyelitis, discitis, encephalitis, meningitis, ophthalmitis, and cranial neuritis.

Etiology: Cat scratch is caused by Bartonella henselae, a gram-negative bacillus. The hallmark is painful lymphadenopathy at the site of inoculation, although most patients remain afebrile and have no constitutional symptoms. Although most cases are asymptomatic, in 5% to 10% of infections, dissemination does occur, commonly affecting cervical lymph nodes.21 The clinical diagnosis is often confirmed with serologic testing.

Imaging: On ultrasonography, the affected areas show multiple enlarged and hypoechoic lymph nodes, with enhanced through transmission, as well as increased echogenicity of inflamed surrounding soft tissues.21 Doppler ultrasonography shows hyperemia, and CT imaging reveals enlargement of lymph nodes, usually with central areas of hypodensity (Fig. 15-7).22

Treatment: Unless severe, most cases resolve without antimicrobial therapy. Rifampin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole have shown effectiveness and are usually reserved for disseminated disease.23 Follow-up imaging is only necessary in patients who do not improve with antibiotic therapy.

Infectious Mononucleosis

Overview: Infectious mononucleosis is a common disorder usually seen in teenagers and young adults. The annual incidence in the United States is roughly 500 cases for every 100,000 persons.24 Diagnosis is based on clinical findings, and screening may be done with a rapid monospot test for heterophile antibodies.

Etiology: Infectious mononucleosis is an acute self-limiting disorder caused by the Epstein-Barr virus. Transmission usually occurs through infected saliva. Patients commonly present with acute pharyngotonsillitis, fever, malaise, and cervical or generalized lymphadenopathy. Splenomegaly is a frequent finding.

Imaging: Patients with infectious mononucleosis do not routinely require imaging. However, this disease may mimic other infectious and malignant processes, and imaging may be performed to determine the extent of involvement. Findings on CT are nonspecific but include adenoidal and tonsillar enlargement, as well as diffuse lymph node enlargement with little to no surrounding inflammatory changes (Fig. 15-8).25

Figure 15-8 Infectious mononucleosis in a 15-year-old female with sore throat, difficulty swallowing, and fatigue.

Coronal reconstructed contrast enhanced computed tomography image demonstrates nonspecific enlargement of the adenoids (A) and tonsils (T). No fluid collections were seen, and no deep neck extension was identified.

Treatment: Infectious mononucleosis is treated with supportive care. It is recommended that contact sports be avoided for at least 3 weeks following diagnosis to reduce the chances of splenic rupture.24 The use of corticosteroids and antiviral medication such as acyclovir or valacyclovir has been suggested, but the recommendation lacks sufficient supporting data. Prognosis is excellent with the exception of possible mortality in splenic rupture cases.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Overview: Benign cervical lymphadenopathy is one of the most common manifestations in children who are positive for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HIV can also cause mediastinal and generalized lymphadenopathy. Imaging is not required for the diagnosis but should be considered along with biopsy if a neck mass persists or worsens, to rule out other causes such as malignancy.

Etiology: The lymphadenopathy of HIV is usually symmetric, painless, and extensive. Although generalized lymphadenopathy in patients with HIV is considered benign, the differential diagnosis includes Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, metastatic disease, and multiple infections.26 Children with HIV may present with parotid gland enlargement caused by lymphocytic infiltration and lymphoepithelial cystic and solid lesions.

Imaging: Prominent adenoids are present on MRI and CT in 35% of patients who are HIV positive.27 Numerous bilateral enlarged lymph nodes are also a common finding. Ultrasonography may show multiple parotid hypoechoic cystic and solid lesions of varying size. On CT, multiple, low attenuation, and bilateral lymphoepithelial lesions are usually seen.26

Treatment: The frontline therapy for the treatment of HIV is multiple antiretroviral drugs, including nucleoside and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, and fusion inhibitors. Although benign cervical lymphadenopathy in patients with HIV does not require specific treatment, biopsy may be necessary to rule out other etiologies.

Sialoadenitis

Overview: Sialoadenitis is a relatively common condition most often affecting the parotid and submandibular glands. Inflammation is the most common etiology of parotid gland enlargement, and viral infection is the most common pathology. The diagnosis of viral infection is usually made on clinical grounds, and thus, imaging of these conditions is usually not indicated. Although many cases are caused by viruses and are self-resolving, sialolithiasis can cause recurrent episodes of inflammation.

Etiology: Sialoadenitis commonly presents as a swollen, enlarged gland and fever. Sialoliths and viruses are the two most common causes. Acute bacterial (suppurative) sialoadenitis is uncommon in children, but recurrent parotitis is occasionally caused by Streptococcus viridians. Recurrent sialoadenitis can be caused by sialoliths, which most commonly affect the submandibular gland. Up to 85% of submandibular gland stones arise within the Wharton duct.28 Mumps is, by far, the most common viral cause of sialoadenitis, usually affecting the parotid glands bilaterally.29 Other viruses include HIV, influenza, and Coxsackie. Chronic salivary gland inflammation is usually caused by recurrent bacterial infections, autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren syndrome, or sarcoidosis. Lymphadenitis affecting other regions of the neck can also cause enlargement of the intraparotid lymph nodes. This is related to the fact that the parotid gland is the only salivary gland to become encapsulated after the development of the lymphatic system, resulting in the presence of intraglandular lymph nodes.

Imaging: Ultrasonography has a role in detecting superficial drainable abscesses. However, it does not help visualize the deep neck to determine the full extent of disease. Nonenhanced CT is the best modality to identify salivary calculi, although contrast is needed to evaluate drainable fluid collections (Fig. 15-9).30

Figure 15-9 Sialoadenitis in a 17-year-old male with left jaw pain and tenderness.

Axial unenhanced computed tomography image shows a large calcification in the expected location of the submandibular (Wharton) duct (arrow).

On ultrasonography, parotitis appears as an enlarged gland, with heterogeneously decreased echogenicity and irregular borders. Intraparenchymal hypoechoic foci may be found, representing small salivary fluid collections, nodes, or small abscesses.29 Color Doppler shows hyperemia. CT shows gland enlargement with diffuse enhancement (Fig. 15-10). The presence of a low-attenuation collection with peripheral enhancement suggests an abscess.29 Recurrent sialoadenitis on ultrasonography manifests as an enlarged gland, containing several 2- to 4-mm hypoechoic areas that represent foci of pooled salivary secretions.

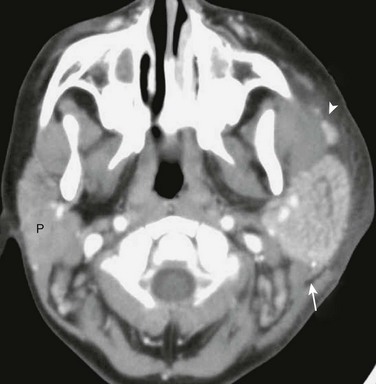

Figure 15-10 Parotitis in a 6-year-old male with painful left cheek swelling.

Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography image demonstrates an enlarged, enhancing left parotid gland (arrow) as well as similar changes in the accessory parotid tissue (arrowhead) along the course of the parotid (Stensen) duct. Note inflammatory stranding in the left cheek subcutaneous fat and the normal right parotid gland (P).

Treatment: Patients with sialoliths can be treated medically with hydration, gland massage, and sialogogues such as cevimeline or pilocarpine to increase saliva production in an attempt to flush out stones. Surgical excision may be required if symptoms do not resolve with conservative management. Total excision of the gland may also be necessary if multiple stones are present.28 Viral sialoadenitis usually only requires supportive treatment.

Boyd, ZT, Goud, AR, Lowe, LH, et al. Pediatric salivary gland imaging. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:710–722.

McKellop, JA, Bou-Assaly, W, Mukherji, SK. Emergency head & neck imaging: infections and inflammatory processes. Neuroimag Clin North Am. 2010;20(4):651–661.

Meuwly, JY, Lepori, D, Theumann, N, et al. Multimodality imaging evaluation of the pediatric neck: techniques and spectrum of findings. Radiographics. 2005;25(4):931–948.

Rana, RS, Moonis, G. Head and neck infection and inflammation. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49(1):165–182.

References

1. Gerber, MA. Diagnosis and treatment of pharyngitis in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52(3):729–747.

2. Ungkanont, K, Yellon, RF, Weissman, JL, et al. Head and neck space infections in infants and children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112(3):375–382.

3. Scott, PM, Loftus, WK, Kew, J, et al. Diagnosis of peritonsillar infections: a prospective study of ultrasound, computerized tomography and clinical diagnosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113(3):229–232.

4. Weber, AL, Siciliano, A. CT and MR imaging evaluation of neck infections with clinical correlations. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38(5):941–968.

5. Kushawaha, A, Popalzai, M, El-Charabaty, E, et al. Lemierre’s syndrome, reemergence of a forgotten disease: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:6397.

6. Gudinchet, F, Maeder, P, Neveceral, P, et al. Lemierre’s syndrome in children: high-resolution CT and color Doppler sonography patterns. Chest. 1997;112(1):271–273.

7. Peer Mohamed, B, Carr, L. Neurological complications in two children with Lemierre syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(8):779–781.

8. Masterson, T, El-Hakim, H, Magnus, K, et al. A case of the otogenic variant of Lemierre’s syndrome with atypical sequelae and a review of pediatric literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(1):117–122.

9. Waterman, JA, Balbi, HJ, Vaysman, D, et al. Lemierre syndrome: a case report. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23(2):103–105.

10. Lalakea, M, Messner, AH. Retropharyngeal abscess management in children: current practices. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121(4):398–405.

11. Grisaru-Soen, G, Komisar, O, Aizenstein, O, et al. Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscess in children—epidemiology, clinical features and treatment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(9):1016–1020.

12. Restrepo, R, Oneto, J, Lopez, K, et al. Head and neck lymph nodes in children: the spectrum from normal to abnormal. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(8):836–846.

13. Gosche, JR, Vick, L. Acute, subacute, and chronic cervical lymphadenitis in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15(2):99–106.

14. Hudgins, PA. Nodal and nonnodal inflammatory processes of the pediatric neck. Neuroimaging Clin North Am. 2000;10(1):181–192. [ix].

15. Maurer, K, Unsinn, KM, Waltner-Romen, M, et al. Segmental bowel-wall thickening on abdominal ultrasonography: an additional diagnostic sign in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(9):1013–1016.

16. Amir, J. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial lymphadenitis in children: diagnosis and management. Isr Med Assoc J. 2010;12(1):49–52.

17. Lindeboom, JA, Smets, AM, Kuijper, EJ, et al. The sonographic characteristics of nontuberculous mycobacterial cervicofacial lymphadenitis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(10):1063–1067.

18. Moon, WK, Han, MH, Chang, KH, et al. CT and MR imaging of head and neck tuberculosis. Radiographics. 1997;17(2):391–402.

19. Robson, CD, Hazra, R, Barnes, PD, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection of the head and neck in immunocompetent children: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(10):1829–1835.

20. Carithers, HA. Cat-scratch disease. An overview based on a study of 1,200 patients. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139(11):1124–1133.

21. Garcia, CJ, Varela, C, Abarca, K, et al. Regional lymphadenopathy in cat-scratch disease: ultrasonographic findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30(9):640–643.

22. Wang, CW, Chang, WC, Chao, TK, et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of cat-scratch disease: a report of two cases. Clin Imaging. 2009;33(4):318–321.

23. Florin, TA, Zaoutis, TE, Zaoutis, LB. Beyond cat scratch disease: widening spectrum of Bartonella henselae infection. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1413–e1425.

24. Luzuriaga, K, Sullivan, JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):1993–2000.

25. Ludwig, BJ, Foster, BR, Saito, N, et al. Diagnostic imaging in nontraumatic pediatric head and neck emergencies. Radiographics. 2010;30(3):781–799.

26. Reisacher, WR, Finn, DG, Stern, J, et al. Manifestations of AIDS in the head and neck. South Med J. 1999;92(7):684–697.

27. Yousem, DM, Loevner, LA, Tobey, JD, et al. Adenoidal width and HIV factors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(9):1721–1725.

28. Williams, MF. Sialolithiasis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1999;32(5):819–834.

29. Lowe, LH, Stokes, LS, Johnson, JE, et al. Swelling at the angle of the mandible: imaging of the pediatric parotid gland and periparotid region. Radiographics. 2001;21(5):1211–1227.

30. Yousem, DM, Kraut, MA, Chalian, AA. Major salivary gland imaging. Radiology. 2000;216(1):19–29.