42

Induction of labour

Introduction

Induction of labour is indicated when the risks of continuing the pregnancy are felt to be greater than the risks of ending the pregnancy. Induction is usually carried out in the interest of fetal well-being and less commonly, for maternal reasons. The decision is often difficult, particularly at pre-term gestations, and many factors, including the availability of neonatal facilities, need to be considered. Labour should not be induced until there has been a careful discussion with the mother about the pros and cons of the induction.

It should be noted that ‘induction’ is different from ‘augmentation’. Induction refers to the process of starting labour and can only be applied to a mother who is not already in labour. Augmentation describes the process of accelerating labour after it has already started.

Fetal indications

![]() Post-dates – usually between 41 and 42 weeks’ gestation

Post-dates – usually between 41 and 42 weeks’ gestation

![]() Fetal growth restriction with risk of fetal compromise (based on estimated growth and fetal monitoring. There may be associated pre-eclampsia

Fetal growth restriction with risk of fetal compromise (based on estimated growth and fetal monitoring. There may be associated pre-eclampsia

![]() Certain diabetic pregnancies

Certain diabetic pregnancies

![]() Deteriorating haemolytic disease of the newborn (rare).

Deteriorating haemolytic disease of the newborn (rare).

Maternal indications

![]() Pre-eclampsia. This is a condition in which both maternal and fetal interests are relevant. While it may, for example, be appropriate to induce for mild pre-eclampsia at term, the pre-eclampsia would need to be severe in a markedly preterm infant

Pre-eclampsia. This is a condition in which both maternal and fetal interests are relevant. While it may, for example, be appropriate to induce for mild pre-eclampsia at term, the pre-eclampsia would need to be severe in a markedly preterm infant

![]() Deteriorating medical conditions (cardiac or renal disease, severe systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE)

Deteriorating medical conditions (cardiac or renal disease, severe systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE)

![]() Antepartum haemorrhage.

Antepartum haemorrhage.

The decision to induce labour depends on the balance between the risks of continuing fetal surveillance and the risks of induction and pre-term delivery. Induction risks are largely related to the use of ‘oxytocics’, the preparations that are used to stimulate uterine activity. The side-effect of greatest concern is that of uterine hyperstimulation, which carries the risk of fetal compromise. The process of induction may also be associated with increased obstetric intervention, particularly if carried out before 41 + weeks’ gestation. Finally, induction may be unsuccessful and the obstetrician may feel compelled to undertake a caesarean section that would not otherwise have been necessary.

Before induction, the gestation should again be confirmed, the presentation checked and any contraindications (e.g. placenta praevia) excluded. It is important to note that real caution is required in those who have had a previous caesarean section or previous uterine surgery, as induction carries an increased risk of uterine scar rupture, and many clinicians would consider these as contraindications, unless the cervix was very favourable. Repeat elective caesarean may be a safer option for mother and baby in this scenario. In addition, grand multiparity and a history of previous precipitate labour also carry increased risks of hyperstimulation.

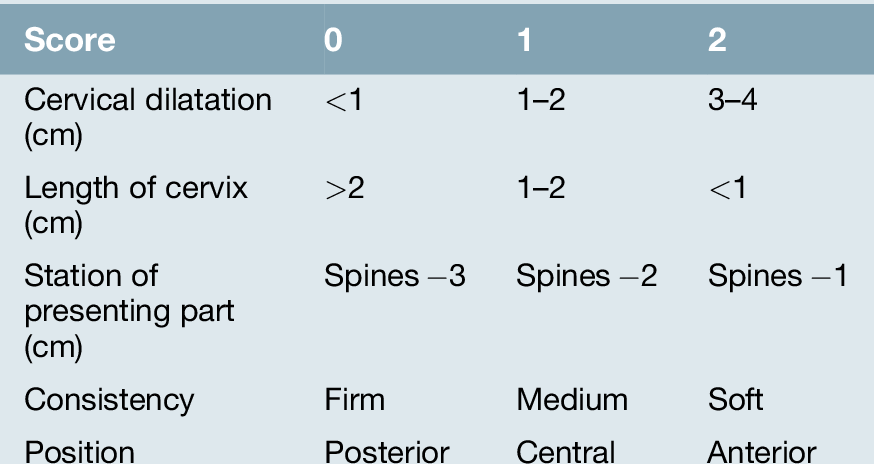

The decision about which technique is the most appropriate depends on the cervix, as assessed by the Bishop’s scoring system (Table 42.1 and Box 42.1):

![]() if the score is ≤ 6, the cervix should be ‘ripened’ with prostaglandins (e.g. gel or pessary)

if the score is ≤ 6, the cervix should be ‘ripened’ with prostaglandins (e.g. gel or pessary)

![]() if > 6, either prostaglandins or artificial rupture of the membranes ± syntocinon may be considered (there may be greater patient satisfaction with the former, but the latter may allow more control).

if > 6, either prostaglandins or artificial rupture of the membranes ± syntocinon may be considered (there may be greater patient satisfaction with the former, but the latter may allow more control).

Unfavourable cervix

Prostaglandins

As discussed on page 322, prostaglandins promote cervical ripening and stimulate uterine contractility. They have been administered by the oral, parenteral and vaginal routes, as well as directly through the cervix and infused into the extra-amniotic space. The main side-effect is of gastrointestinal upset with nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, which may occur in up to 50% of instances depending on the route of administration. Vaginal preparations have fewer side-effects than oral or parenteral preparations.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is used in clinical practice. A gel or tablet is inserted into the posterior fornix and, if there is no uterine activity, the cervix is reassessed after 6 h. If the Bishop’s score is < 7, further prostaglandin is given and the cervix reassessed again 6 h later. Further doses may then be given or the patient left for 12–18 h (e.g. overnight). If at any stage the Bishop’s score is > 6, an artificial rupture of the membranes may be performed, reassessment made in a further 2 h and syntocinon started if there is no further change. Prostaglandins should not be given if there is regular uterine activity. Misoprostol (a methyl ester of prostaglandin E1) can also be used either orally or vaginally but carries a higher incidence of hyperstimulation than do preparations of PGE2.

Sustained-release preparations are also available in the form of a polymer-based vaginal insert containing PGE2, with retrieval thread. The preparation is placed in the posterior fornix for 12 h, after which it is removed. This technique has the advantage that the insert can be removed if hyperstimulation develops, and there is some evidence that it is associated with a reduced likelihood of operative vaginal delivery compared with other prostaglandin formulations.

These preparations all cause uterine contractions and therefore have the potential to reduce uterine blood flow and compromise the fetus. Cardiotocography (CTG) monitoring is therefore indicated.

Favourable cervix

If the cervix is favourable, the choice is between:

![]() prostaglandins

prostaglandins

![]() artificial rupture of the membranes

artificial rupture of the membranes

![]() artificial rupture of the membranes and syntocinon.

artificial rupture of the membranes and syntocinon.

It remains unclear which of these is the superior induction method, but there is some evidence that maternal satisfaction and likelihood of achieving vaginal delivery within 24 h is greater with prostaglandins. The requirement for analgesia and the rates of postpartum haemorrhage may be lower in this group as well.

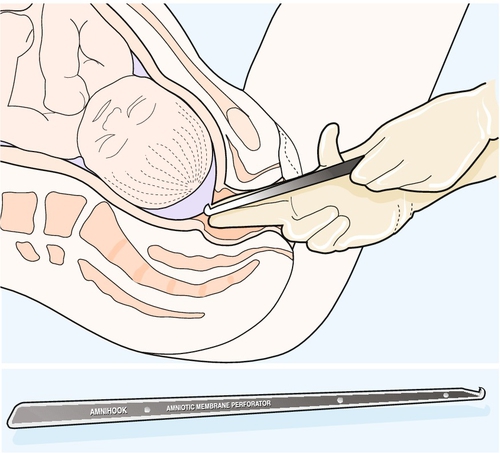

Artificial rupture of the membranes (ARM)

Artificial rupture of the membranes (or ‘amniotomy’) may be used to induce labour in those with a sufficiently favourable cervix and is also used for augmentation of labour. It probably works by a combination of uterine decompression and local prostaglandin release. Another advantage is that it allows assessment of the colour of the liquor (see Meconium staining of the liquor, p. 333).

ARM has been advocated, by some, for all labours, spontaneous or induced. This is surrounded by a degree of controversy, as it can be argued that there is less cushioning of the fetal head and therefore a greater incidence of fetal heart rate decelerations. Indeed, routine amniotomy alone does not shorten the duration of the first stage of labour, improve maternal satisfaction or improve Apgar scores at delivery, but confers a trend to an increased risk of caesarean section.

Before ARM, vaginal examination is performed. The fetal head should be well applied to the cervix to minimize the risk of cord prolapse. With asepsis, the tips of the index and middle fingers of one hand should be placed through the cervix onto the membranes (Fig. 42.1). The amniotomy hook should be allowed to slide along the groove between these fingers (hook pointing towards the fingers) until the cervix is reached. The point is then turned upwards to break the membrane sac. Liquor is usually seen, but may be absent in oligohydramnios or with a well-engaged head. Cord prolapse should be excluded before removing the fingers and then the fetal heart should be rechecked. Absent liquor following artificial rupture of the membranes should be treated in the same way as meconium staining, with careful monitoring of the fetal condition.

Syntocinon

This may be used for induction after ARM with a favourable cervix, or for augmentation of a slow non-obstructed labour. It should only be started after membrane rupture, and continuous CTG monitoring is mandatory. The dose should be titrated against the contractions, aiming for not more than six to seven contractions every 15 min. Induction of labour with syntocinon is less effective than vaginal prostaglandin (in terms of achieving vaginal delivery within 24 h) and is more likely to be associated with epidural analgesia.

In contrast to the effects of ARM alone for labour augmentation, early ARM and oxytocin reduces the duration of the first stage of labour by about 90 min, and confers a trend to a reduction in rates of caesarean section, but has no effect on maternal satisfaction or neonatal outcome.

Other methods of induction

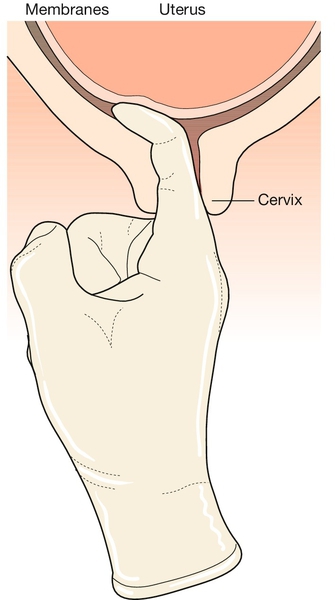

Membrane sweep

This involves performing a vaginal examination and inserting a finger through the internal cervical os to separate the membranes from the uterine wall, thus releasing endogenous prostaglandins (Fig. 42.2). It is often uncomfortable for the mother. If a sweep is carried out once after 40 weeks’ gestation, it doubles the incidence of spontaneous labour over controls, especially in those with a low Bishop’s score. The risk of infection is considered to be minimal.

Anti-progesterones

Mifepristone, a progesterone antagonist, has been studied in early pregnancy and has been shown to increase uterine activity and lead to cervical softening. Research into its use as an induction agent later in pregnancy has shown promising results, but it is not yet in clinical use because of uncertainty about fetal safety.

Mechanical methods of induction of labour

Several mechanical methods of induction of labour are available including laminaria tents, intracervical insertion of a Foley catheter, and other balloon devices inserted through the cervix. Increasing evidence suggests that these devices are as effective as prostaglandins for achieving vaginal delivery within 24 h (with the possible exception of multiparous women), and are associated with similar rates of caesarean section. Mechanical methods confer lower rates of hyperstimulation compared to vaginal prostaglandins. When compared with oxytocin induction alone, caesarean section rates appear to be lower with mechanical methods.

Failed induction

Despite the above techniques, induction of labour is sometimes unsuccessful. The plan then depends on the reason for the induction. If it was for some significant fetal or maternal indication, there is probably little choice but to consider caesarean section. If, on the other hand, the induction was for some less pressing reason (e.g. for post-dates), then it may be reasonable to consider a more conservative approach including a repeat attempt at induction at a later date. This would depend on an informed discussion with the woman and her partner.