The indications for a particular treatment method should be established not only on the basis of the clinical diagnosis but also following an analysis of the pathogenesis so as to identify which lesion is most important at a given moment and is therefore likely to be the most effective object of therapy. Every therapeutic action should therefore result from a fresh examination, to keep up to date with the ongoing development of the patient’s condition.

In this setting it is of the utmost importance to identify chain reaction patterns of dysfunctions and to pinpoint the most relevant link in the chain. In establishing the indications for a particular treatment, it follows that no therapeutic intervention should be applied before examination of the patient has been completed and the findings have been meticulously analyzed.

If therapy is determined according to the principles set out here, it is likely to be effective and the condition of the patient should be found to have changed at follow-up examination. If the patient’s condition is unchanged, treatment was not adequate and should (generally) not be repeated.

Critical assessment of the preceding treatment and ongoing audit and review are essential here. To reiterate: this is primarily a question of analyzing the factors contributing to the pathogenesis and not simply of conventional clinical diagnosis. This attitude rules out an indiscriminate routine approach (e.g. ‘a series of intradermal injections’ or ‘a series of infiltrations’), presupposes critical assessment of any preceding treatment, and thus also enables the treatment program to be corrected in light of the results obtained with preceding treatments (evidence-based strategy).

5.1. Manipulation

5.1.1. Indications

Manipulative treatment is indicated if there is functional movement restriction (a pathological barrier) of a joint or spinal motion segment, and if this is considered relevant to the patient’s symptoms. In this setting, too, it should be emphasized that the decisive factor is not the clinical condition as such or even the clinical diagnosis (headache, dizziness, low-back pain), but rather the importance of the movement restriction for the pathogenesis.

Once this concept has been fully grasped, definition of the action required in spondylosis, disk herniation, osteoporosis, or ankylosing spondylitis is a straightforward matter: these conditions in themselves do not form the object of manipulative treatment. Nevertheless, if it is felt that movement restriction is a factor in patients with these diagnoses, then the restriction should be treated with a manipulative technique that is appropriate in the given circumstances.

Given the questionable importance of spondylosis for the pathogenesis, it is highly probable that diagnosis of a movement restriction will be the key finding.

In disk herniation, concomitant movement restriction may often cause the patient’s condition to deteriorate considerably and in such cases manipulation can be very successful. While it is far from easy to predict a successful outcome, it is always worth making an attempt with an appropriate technique.

Scoliosis is certainly not an object for manipulation, as in itself the condition does not usually cause pain. If a patient with scoliosis feels pain, and movement restrictions are diagnosed, these are far more likely to be the cause of that pain and should be treated. Manipulation is indicated if movement restrictions interfere with remedial exercise.

In both osteoporosis and juvenile osteochondrosis, stiffness (leading to immobility) will cause the patient’s condition to deteriorate. Adequate gentle mobilization techniques are therefore indicated to restore mobility.

Spondylolisthesis and basilar impression cannot be influenced by manipulation, but in clinical terms they are more often than not symptom-free. Here, too, dysfunctions associated with movement restrictions can be, and frequently are, the true cause of discomfort.

In ankylosing spondylitis, movement therapy is indicated, and therefore (self-)mobilization techniques are also appropriate; these have to be applied, however, to those segments that still show some degree of mobility.

The reason why manipulation may be regarded as safely indicated in all these patient groups is that the methods advocated in this book are extremely gentle and very effective neuromuscular mobilization techniques. They utilize the inherent muscle forces of the patient rather than those of the practitioner; indeed the practitioner tends to function more in a ‘directorial’ capacity, instructing the patient what to do and frequently allowing the patient to perform self-treatment.

High-velocity, low-amplitude thrust techniques

After gentle mobilization has been performed, the experienced practitioner will sometimes sense that the effect is still not entirely satisfactory; for example, a segment may still not be completely freed from several neighboring segments or, despite a measure of improvement, an area remains that still requires treatment. Preceding mobilization ensures that such a segment is well-prepared for a

high-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA)

thrust. Following the work of

Mierau et al (1988) we know that use of HVLA thrust techniques is followed by temporary hypermobility, and that a very intensive reflex response characterized by hypotonus or reduced muscle tone is achieved, which can be beneficial in radicular compression or entrapment syndromes (e.g. carpal tunnel syndrome). HVLA thrust techniques should be delivered with a minimum of force, and the cracking or popping sound within the joints should never be ‘enforced’ by the practitioner. If the segment has been well prepared for a thrusting maneuver, then the technique should succeed with consummate ease. This also applies to the situation in children who are too young to cooperate; here it is important to exploit the precise moment when they are relaxed. However, this presupposes excellent technical skill.

Table 5.1 Stoddard’s classification of joint mobility

| Classification |

Description |

| 0 |

No mobility, ankylosis, not suitable for manipulative treatment |

| 1 |

Severe movement restriction, only mobilization techniques to be applied |

| 2 |

Slight movement restriction, both mobilization and thrust techniques can be used |

| 3 |

Normal mobility, best left alone; however, if there is movement restriction in one direction, a thrust technique in the free direction can be useful (Maigne) |

| 4 |

Hypermobility, all types of manipulative treatment should be avoided |

5.1.2. Contraindications

The major technical advances achieved in the field of manual medicine in recent years have brought about a sea change specifically in the area of indications and contraindications. The situation can now be summarized concisely as follows: there is no real contraindication to manipulation and no possibility that patients will be harmed by it. What is contraindicated, however, is poor technique. Nowadays the basic approach comprises mobilization with neuromuscular techniques that primarily make use of the patient’s inherent muscle forces. This would be like forbidding the patient any spontaneous movements. HVLA thrust manipulation is employed to a very limited extent only and the ground is generally thoroughly prepared beforehand using mobilization techniques.

The following

cardinal errors must be avoided:

• Over-frequent use of HVLA thrust techniques.

• Delivering an HVLA thrust before the patient is properly relaxed and before the slack has been taken up.

• Trying to enforce manipulation of any type against protective muscle spasm or in a direction that causes pain.

• Performing cervical manipulation in retroflexion, side-bending, and rotation with traction, especially in cases where the patient does not tolerate this position.

• Repeating HVLA thrusts at short intervals (i.e. of less than two weeks); in this context, even over-zealous examination of mobility in a painful direction may be contraindicated.

In the debate surrounding contraindications, repeated reference is made to serious incidents and even fatalities, such as those reported by Dvorák & Orelli (1985), Grossiord (1966), Krueger & Okazaki (1980), Lorenz & Vogelsang (1972) and cited in the memorandum issued by the German Association of Manual Medicine (1979). Basing their calculations on the results of a questionnaire sent to members of the Swiss Association of Manual Medicine, Dvorák & Orelli (1985) computed the number of serious complications after manipulation (thrust techniques) to be 1:400000. By far the most important cause of serious complications is undoubtedly injury to the vertebral artery, the wall of which may split longitudinally. Given the low incidence of vertebral artery damage and the rarity of such incidents, more recent publications (up to 2004) have suggested that these findings may be coincidental.

Unfortunately, an almost constant feature of the literature cited is a failure to specify the particular technique that was held responsible for the complications in question: this is rather like discussing

postoperative complications without giving details of the surgical technique used. One exception, however, is the publication by Dvorák & Orelli (1985), which includes the following highly characteristic account:

A 35-year-old woman collapsed while attending a funeral and suffered from wry neck for three weeks afterward. Within the space of a few days she underwent HVLA thrust manipulation three times, administered by a qualified, experienced chiropractor. The patient was supine and manipulation consisted of passive rotation, reclination, and side-bending of the head. This was followed immediately by a short period of unconsciousness and later by tetraplegia. The patient was extubated after mechanical ventilation for 36 hours and administration of dexamethasone. After four months the patient was symptom-free apart from slight unsteadiness of gait. HVLA thrust techniques in acute wry neck are questionable in themselves, but to use the dangerous combination of ‘rotation, reclination, and side-bending’ is to court disaster. Another grave error was to repeat the thrusts in quick succession within the space of a few days because the patient’s condition did not show any improvement. In the few instances where detailed case reports are available, serious complications have indeed occurred most frequently when HVLA thrust techniques are repeated within a short space of time.

It should be emphasized here that HVLA thrust techniques are inappropriate for painful and severe movement restrictions, even if several adjacent segments are involved simultaneously. In such cases, HVLA thrusts are not only traumatizing but also ineffective, whereas neuromuscular techniques have proved outstandingly beneficial. For this reason, HVLA thrust techniques hardly ever form the initial component of therapy. The following contraindication may be inferred: if it is a mistake to perform thrust manipulation in the painful direction where there is major movement restriction, then use of this technique is also contraindicated where pain and gross movement restriction are present in all directions. In reversible functional movement restrictions, a distinction is made in any case between the direction of restriction and the direction of ease; movement restriction in all directions does not suggest dysfunction and therefore does not constitute an indication for manipulation.

For obvious reasons, manipulation of any kind is out of place in hypermobility. While this does not mean that no movement restriction should be treated in a hypermobile patient, it would be better to avoid thrust techniques because temporary hypermobility always follows any thrust maneuver.

Other contraindications include

destructive conditions of an inflammatory or neoplastic nature. It is clear that no one would try to treat this type of pathology by manipulation; unfortunately, particularly in the initial stages of such conditions, diagnostic error is often unavoidable. The specialist usually sees such patients in hospital, at a later stage, when the putative diagnosis has already become clearer. Nevertheless, with modern-day techniques, these patients should come to no more harm than from the administration of analgesics. If, in a case of diagnosed tumor pathology, coexisting movement restriction is considered harmful to the patient’s condition, there is no reason why such a restriction should not be treated with an appropriate technique (see Case study 2 in

Section 4.21.2).

While working at the neurology clinic in Prague-Vinohrady, I deliberately gave manipulation at the craniocervical junction to a patient with a decompensating acoustic neuroma; he was then able to be referred to the neurosurgery clinic in a well-compensated state. It is regrettable that a vertebral artery syndrome is considered to be a contraindication in this setting. Admittedly, treatment must only ever be given in a direction that is well tolerated, but there are few disorders where restrictions involving the craniocervical junction are more disastrous.

5.1.3. Traction

Traction is essentially a form of mechanotherapy or manipulation, but unlike other methods of manipulation it is generally accepted in traditional medicine. Within the framework of manipulative techniques, traction of the cervical and lumbar spinal column has a specific role in radicular compression syndromes in those spinal regions and in disk herniation. In fact, traction can also be useful for diagnosis: if it relieves discomfort in the lumbar region, then the diagnosis of a herniated disk is corroborated. Traction is also indicated in acute wry neck and low-back pain.

5.2. Soft-tissue manipulation

Soft tissue, in particular the deeper layers including the fascia and connective tissue, is intimately connected with the locomotor system, muscles, and joints. It is the function of soft tissue to be stretchable while yet able to resist stretch, and to be capable of being shifted while yet able to resist shifting. All this should take place in harmony with the locomotor system and may involve considerable ranges of movement.

The same also applies for the viscera: there are no standard measures whatsoever for the degree to which the internal organs may also move. Changes in soft tissue have usually been considered to be reflex changes, that is secondary changes. This is not always the case, however, particularly in the chronic stage of painful conditions, and in endocrine and metabolic disorders. The tissue changes then form what is termed a ‘terrain’ (or constitutional factor).

Clinically, a physiological and a pathological barrier can be detected in all soft tissue: both types of barrier constitute a possible indication for therapy, enabling disordered function to be corrected in precisely the same way as in restricted joints. If the soft-tissue changes are significant, they produce reflex inhibition of the locomotor system; it is then advisable to treat such soft-tissue lesions before performing joint mobilization, as the treatment itself may have a considerable mobilizing effect.

5.2.1. Skin stretching

This technique is specific for hyperalgesic zones (HAZs). It has an effect similar to that of

Kibler’s skin-fold rolling test (1958) and of connective tissue massage as advocated by

Leube & Dicke (1951). However, it is absolutely painless and may also be used by the patient for self-treatment. The technique can also be applied to very small skin areas, such as the skin fold between fingers or toes, where HAZs may develop, especially in radicular syndromes radiating to the fingers or toes. HAZs are a useful sign of a radicular lesion and their treatment can be highly effective.

Examination usually starts with a test for skin drag by gently stroking the skin surface with a fingertip. Skin drag in a HAZ is heightened due to increased moisture (sweating) and so permits rapid identification of the area where skin stretching should be performed.

5.2.2. Stretching a soft-tissue fold (connective tissue)

The deeper layers of connective tissue can be folded and, after the barrier has been engaged, stretched. This technique is particularly effective for treating short or taut muscles and scars. The fold can be formed between the fingers or sometimes between the full length of the lateral edges of both hands. Stretching should never involve compression. Once the barrier is engaged, release is obtained spontaneously.

5.2.3. Application of pressure

In cases where a tissue fold cannot be formed, the application of very light pressure can obtain tissue release. The pressure applied is just sufficient to sense the moment of increased resistance when the barrier is engaged. After a brief latency period, the resistance disappears and the practitioner’s finger spontaneously sinks more deeply into the tissue. This method is especially effective for deep-lying trigger points (TrPs) and scars, particularly in cases of painful resistance in the abdominal cavity.

5.2.4. Restoration of deep tissue mobility

5.2.5. Treatment of (active) scars

Scars are located chiefly in the soft tissue, involving all its layers. Where healing is uncomplicated, a scar will be asymptomatic and all the layers involved will stretch and shift like those in the surrounding tissue. However, if healing is not straight forward, but more frequently for no apparent reason, many years later, a scar may become active in stressful situations and may even recurr after successful treatment. Examination will disclose resistance in some or all of the tissue layers penetrated by the scar. Such a scar is termed ‘active.’ Pathological barriers will then be found in all soft-tissue layers, and the patient will report pain when these are examined. Because a scar generally passes through several soft-tissue layers, it can be a particularly rich source of pathology, causing dysfunctions of muscles and joints.

The process of scar examination begins with a test for skin drag, often the most rapid guide as to what is happening. However, the diagnosis can also be difficult. Following surgery the operative field may (for esthetic reasons) be at some distance from the surface wound. Because surgery is often performed only by laparoscopy or with a laser, it is frequently necessary to rely on findings elicited by deep palpation. The same is true for internal injuries without surface scarring, for example following a difficult childbirth. In this setting (compared with the situation in organic disease), palpation of the release phenomenon is of major diagnostic significance. Typically, the diagnosis here can be helped by the finding that locomotor symptoms had their onset shortly after surgery or trauma.

Undiagnosed active scars cause problems that keep recurring until they have been treated; however, their treatment can bring surprising

successes, described by their discoverer

Huneke (1947) as the ‘instant relief phenomenon.’ Huneke himself injected novocaine into scar tissue and attributed the resultant effect to this intervention. However, simple needling yields the same result. Nevertheless, therapy using soft-tissue techniques is far more precise because it is based on the diagnosis of all scar layers. The term ‘instant relief phenomenon’ emphasizes not only the immediate effect but also the fact that all symptoms disappear with a single intervention. This is generally over-optimistic; the soft tissue in the vicinity of a scar often requires repeated treatment, and not infrequently the scar is just one of a larger number of factors in the pathogenesis. It may itself also be prone to recur.

5.2.6. Relaxation of muscles

Post-isometric relaxation (

PIR) is the specific therapy for muscle tension with or without TrPs. Here, too, the first step is to take up the slack by lengthening the muscle so as to engage the barrier. This method, which will be described in detail in

Section 6.6, has a similar effect to the spray and stretch method of

Travell & Simons (1999) and is effective not only on TrPs in muscle, but also on the points where tensed muscles attach to the periosteum, and on referred pain in particular. PIR is painless and is suitable for use in a self-treatment setting. We routinely combine it with

reciprocal inhibition (

RI) achieved by antagonist stimulation. It should be emphasized here that the vast majority of TrPs can be treated via reflex mechanisms merely using minimal pressure and generally in the context of chain reaction patterns. However, chronic TrPs do exist; these need to be diagnosed and then treated with painful needling or with hard ‘traumatizing’ massage.

5.3. Reflex therapy

This acts on the same structures as soft-tissue manipulative therapy, but is generally less specific and is consistent with the traditional methods employed by physical therapists.

5.3.1. Massage

Bearing this in mind, it would seem that massage is a universal method that is potentially applicable in all reflex changes produced by pain (or nociceptive stimuli); and indeed that is the case. Massage is pleasurable, routinely brings relief and is therefore also very popular with patients. Unfortunately, the effect is usually only short-lived, whereas the procedure is very time-consuming. At the same time, some massage techniques can be quite painful.

Massage is invariably a purely passive form of treatment, demanding no active involvement whatsoever from the patient. For this reason massage is indicated only as a preparation for other, more specific and hence more effective treatment modalities, and is not the therapy of choice for locomotor system dysfunction.

The term ‘reflex massage’ is also used occasionally. It is sufficient to point out that any massage, any palpatory activity, triggers a reflex, depending on the tissue that is being massaged.

5.3.2. Exteroceptive stimulation

Although this method does not exploit the barrier phenomenon, it is nevertheless appropriate for inclusion here because it is a manual method that is used in a targeted manner in response to specific findings. It is based primarily on stroking, which is indicated in circumstances characterized by minor changes in tactile perception. From a purely theoretical standpoint, afferent conduction is the prerequisite for control by the nervous system. Exteroceptive stimulation is one of the few methods to take account of this. It is used not for gross neurological disorders, but merely for dysfunctions that are comparable to a HAZ.

These dysfunctions are most clearly evident on the soles of the feet where an asymmetrical response to stroking or brushing is often observed and patients also confirm that they are aware of the difference. With greater experience it is possible to discern that changes in muscle tone are also consistent with minor asymmetries in tactile perception. These asymmetries can be corrected by stroking. However, the practitioner must be able to sense the reaction during stroking. Stroking (our preference is to trace numbers and letters – proprioception) in asymmetric tactile perception on the soles of the feet is so effective that it is invariably indicated, and is performed on the side that is considered abnormal.

5.3.3. Local anesthesia – needling

Local anesthesia and needling are among the most widely used methods of treating painful lesions. It may appear unorthodox to deal with these two methods together, and yet it should be recalled that one does not simply use local anesthetics to relieve pain for the short period during which the anesthetic has effect. The popularity of local anesthesia is due to the fact that its effect far outlasts the direct (pharmacological) action of the anesthetic. It has further been shown that the effect appears not to be dependent on the local anesthetic injected. In fact,

Kibler (1958) used sodium bicarbonate, and

Frost et al (1980), in a double-blind study, compared the effect of mepivacaine injections with that of physiological saline injections in the management of myofascial pain. It was shown that, if anything, physiological saline solution was more effective than the local anesthetic. The common denominator in all these methods is, of course, the use of the needle.

The effect, however, does appear to depend very much on how precisely the needle touches the pain point. Needling is most effective when the needle is able to reproduce the patient’s spontaneously reported pain and its radiation pattern. In the case of TrPs, a twitch response should be provoked wherever possible, whether a local anesthetic is used or not. If the exact spot is successfully located, then analgesia can be produced immediately simply with a dry needle (

Lewit 1979), both at TrPs and at other pain points.

Injection of local anesthetics is, of course, necessary if the intention is to interrupt conduction in nerve structures, for example in nerve-root infiltration or epidural anesthesia. One special method of using local anesthetics is to raise intradermal blebs, although this technique is advisable only where administration is within a HAZ. Here, too, it is immaterial whether the bleb is produced using a

local anesthetic, physiological saline, or distilled water (although the latter is more painful).It is interesting that, just as after manipulation (so, too, after successful needling or local anesthesia), the immediate relief obtained is often succeeded by a painful reaction lasting for a period of hours, or one or sometimes two days. It is only after this reaction has subsided that the therapeutic effect proper becomes established. For this reason such treatment should not be repeated before seven days have elapsed. Repetition is indicated if improvement has been achieved but there is still some residual pain.

5.3.4. Electrical stimulation

This category includes a variety of methods that ultimately act on the same receptors and therefore produce comparable effects. Pain can be alleviated by reflex mechanisms in response to electrical impulses, diadynamic current or transcutaneous stimulation and many other similar modalities. They compete successfully with more traditional methods such as poultices, cupping, leeches, etc. All these methods, especially if they are used relatively gently, can help to alleviate pain.

5.3.5. Acupuncture

This discussion of reflex therapies must touch briefly on acupuncture, one of the most venerable modalities in this category. Considerable difficulties arise the moment we attempt closer analysis of its mode of action. According to the orthodox view, acupuncture treatment is based on organ diagnoses and less on principles of pathogenesis, although some modern authors (

Bischko (1984), for example) concede that acupuncture works primarily in cases of disturbed function rather than in structural pathology. The choice of acupuncture points is based on ‘meridians’ and is entirely empirical. From a theoretical standpoint, the most questionable issue surrounds the concept of ‘energies’ that are not at all susceptible to measurement. For scientific analysis, therefore, it will be necessary to examine the individual constituent elements that go to make up the system of acupuncture.

One such element is the

effect of needling: this was confirmed as medically effective in an older publication by

Travell & Rinzler (1952) and I myself (

Lewit 1979) described the ‘needling effect’ in 312 pain points in 241 patients. There would seem to be sufficient clinical evidence to support the efficacy of this treatment.

There appears to be a growing tendency among modern Chinese doctors to select their needle insertion points not only according to the traditional ‘meridians,’ but also on the basis of the segmental anatomy of innervation. Instead of needling, electrical stimulation has also been introduced (

Chang 1979).

Melzack et al (1977) have pointed out important analogies between the TrPs of

Travell & Rinzler (1952) and traditional acupuncture points.

Gunn et al (1976) found that of 100 acupuncture loci chosen at random, 70 were motor points in muscles. Other acupuncture loci are attachment points of tendons and ligaments; if these are tender, they can be treated by performing PIR on the muscles for which they serve as attachment points – for example the fibular head (TrP of biceps femoris or by mobilizing the fibular head), or the che-gu (4 equ L14) acupuncture point by PIR of the adductor pollicis brevis.

Patterns of chain reactions (see

Section 4.20) help us to understand functional relationships based on physiological principles and thus might provide a rational explanation for the phenomenon of ‘meridians.’

Careful examination often reveals that many acupuncture points can be tender at palpation and that increased tension can be felt at these sites. This is borne out, too, by the measurement of reduced electrical skin resistance in the vicinity of acupuncture points.

A rational, scientific attitude to acupuncture is important because it might enable us to establish the indication more precisely in the context of dysfunctions; it would then be possible to identify those circumstances where acupuncture might be the treatment of choice.

5.3.6. Soft-tissue manipulation versus reflex therapy

Soft-tissue manipulation techniques act on the same structures that are the targets for most other methods employed in physical (reflex) medicine. Technically, they are based on the diagnosis and correction (release) of a pathological barrier and thus form part of the canon of manual therapy.

The difference between massage and soft-tissue manipulation is primarily that massage, with its relatively rapid rhythmic movements, does not take precise account of the barrier and release phenomenon. Despite the rapid movements involved, massage is far more time-consuming, diagnostic criteria are often lacking, and self-treatment is not really possible.

5.4. Remedial exercise

Having discussed the indications for methods that are intended to act directly on painful dysfunctions, we will now turn our attention to methods targeted at the more complex functions. In this setting, remedial exercise has a prominent role to play.

Two essentially different types of remedial exercise should be distinguished. In the first type, patients learn to use their own muscles to restore joint mobility, to relax their own TrPs and also to treat soft-tissue parts that they can reach themselves. These techniques will be described systematically in conjunction with the corresponding manual therapy techniques.

The second type of remedial exercise is intended to correct faulty movement patterns (or stereotypes), which are associated with muscle imbalance and are frequently the true cause of painful dysfunction. The object of remedial exercise in such cases is to correct a faulty movement pattern that has been diagnosed and is considered relevant to the patient’s problem.

Without this diagnosis of a faulty movement pattern and subsequent assessment of its relevance in terms of the pathogenesis, remedial exercise is simply a frustrating waste of time. It should be the role of the physician to make this diagnosis and assessment. The technical aspects are then the domain of the physiotherapist. A physician who is able to establish the correct indication for remedial exercise should also be able to assess the effect that the physiotherapist has achieved.

The first criterion for establishing the indication, namely the diagnosis of faulty movement patterns and muscle imbalance, often presents an insuperable problem in the acute stage when pain distorts all movements and it is impossible to differentiate between a pain reaction and a faulty movement pattern. Moreover, the patient is also still unable to execute any normal movement patterns.

The second criterion in determining whether remedial exercise is indicated is the relevance of the faulty movement pattern to the patient’s problem. Here the decision can be more difficult, for example, than in the case of a movement restriction or a TrP, because remedial exercise is far more time-consuming and laborious. Muscle imbalances are also common in asymptomatic patients and to embark on a course of remedial exercise in every case would be most unrealistic. Remedial exercise is therefore indicated where we are satisfied that the faulty movement pattern we have diagnosed is so important that, if left uncorrected, the patient’s condition is bound to recur.

Indeed, specific remedial exercise is indicated precisely to prevent these frequent recurrences. Nevertheless, there are cases where the findings are so serious that there is no need to wait for recurrences. One criterion is the degree of muscle imbalance. In other cases we must consider the circumstances that trigger recurrences: for example if they routinely occur when a patient lifts a heavy object or bends forward. In such cases we study the patient’s forward-bending movement pattern and then demonstrate the correct way to bend forward and straighten up again, also while lifting. The same is true for carrying loads, sitting at the computer, etc. However, faulty breathing patterns are the most disastrous of all because they are intimately linked with the stability of the spinal column.

To make remedial exercise as effective as possible, and to make it a routine procedure, it is essential to set clear and attainable goals. This means that we should not set out to achieve ‘ideal movement patterns,’ but instead we should concentrate on the fault that is the chief cause of the recurrent problem. When we do this, it is often possible to obtain results within a short period, after a few clear instructions have been given. However, if we try to achieve more than this, then remedial exercise therapy may take months.

The patient’s general physical condition must also be taken into account: cardiac function, circulation, obesity, generally weakened abdominal musculature after repeated surgery and/or childbirth, recurrent hernias or decompensating scoliosis in old age – any of these may present insurmountable obstacles from the outset.

Despite these limitations, remedial exercise should constitute the most important modality implemented by the physiotherapist for dysfunctions involving the locomotor system. The importance and effectiveness of remedial exercise have increased considerably now that we have a better understanding of how specifically to treat the deep stabilization system of the trunk and feet. This is why it is so crucial to devote time primarily to these active methods of rehabilitation and to a lesser extent to passive procedures such as massage, and the many different forms of electrotherapy.

Finally, there is the question of whether and under what circumstances these remedial exercise methods can be prescribed for preventive purposes. This is a perfectly reasonable consideration given that, in our modern technically advanced world, patterns of harm are continuously inflicted on the locomotor system from childhood. Regrettably, a solution to this problem is difficult to find, mainly because group therapy is not easy to arrange. One possible solution might be to recommend yoga techniques (e.g. breathing exercises, ‘spinal’ techniques, etc.) or methods utilized in Chinese exercise systems (e.g. Tai Chi) and certain strategies advocated in back schools.

5.5. Treatment of faulty statics

The diagnosis of faulty statics has been described in

Section 3.1 and

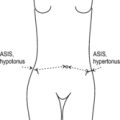

Section 4.2. Contributing causes often include muscle imbalance and external influences (e.g. ergonomic factors), and faulty statics need to be treated accordingly. We will take the opportunity here to deal with the correction of obliquity.

Obliquity in the pelvic region and in the lower part of the lumbar spine can be compensated for with corrective footwear. Because such footwear is beneficial only if it is worn permanently, prescription of this interventional measure must be approached in a purposeful and responsible manner if it is to be effective. Considerable thought must be given to ensure that such an intervention is properly indicated. The decision is relatively straightforward if obliquity is due to fairly recent

trauma, for example a leg-shortening injury or unilateral compression of the lumbar spine. Unilateral (asymmetric)

flat foot as a further possible indication can be best identified on examination if the patient stands on the lateral margins of both feet, causing the pelvis to become horizontal while at the same time the pelvis which deviated to the higher side returns to the mid position. However, because pelvic obliquity in most cases gives rise to

secondary compensation during growth, the decision then becomes far more complex. In such circumstances assessment is impossible without X-ray analysis, as described in

Section 3.1. Ultimately, however, the decision must also be taken on clinical grounds.

Clinically, static pain is a chronic, recurring phenomenon associated with excessive static loading, primarily on standing.

Examination reveals pelvic deviation toward the higher side. When a board of suitable thickness is placed under the foot of the ‘shorter’ leg, the patient’s pelvis should become horizontal and lateral deviation should also be reduced. Since X-ray images demonstrate this result much more precisely, the indication for such correction should be established on the basis of the clinical and X-ray findings before and after placing the board under the patient’s foot.

The type of shoe correction implemented is important in itself. A heel insert fitted inside the shoe is practical, but has the disadvantage that the shoe fits less well. For this reason, it is better to lower (shorten) the heel on the shoe of the longer leg. However, this is practicable only where leg length difference is minimal. Where leg length difference is greater than 2cm, the sole must be thicker on the shoe of the shorter leg, otherwise the foot would be uncomfortable. It is not necessary though to compensate fully for leg-length inequality.

If there is no difference in leg length and the pelvis is level, but obliquity is detected in the lower lumbar spine, this will have implications during both standing and sitting. In this instance corrective compensation must also be provided when the patient is seated by placing a thin board under one ischial tuberosity. X-rays will be required to demonstrate the need for such measures.

The most frequent and most serious fault in sitting is kyphosis due to hypermobility of the lumbar spine. In such cases a back support should be prescribed where the kyphosis peaks. If that is not possible, then it is recommended that the sitting surface should be tilted forward or that the patient should sit in the oriental manner with legs crossed, or on the heels (Japanese fashion), which causes the pelvis to tilt forward.

5.6. Immobilization and supports

In the acute stage of lesions involving the locomotor system, muscle spasm ensures immobilization. The same also applies after trauma, when healing makes immobilization imperative. However, immobilization becomes highly problematic once a condition threatens to become chronic, and if the objective is full recovery, that is restoration of normal function, then immobilization presents an outright obstacle. For this reason immobilization should only ever be a temporary measure in circumstances where the aim is to restore normal function. Permanent immobilization signifies simply that there is no hope of functional recovery.

Unlike immobilization, however, supports need not greatly interfere with mobility while protecting the patient against excessive static loading, an important consideration in sedentary occupations. And it is primarily hypermobile subjects with lax muscles and ligaments who find it difficult to adapt to excessive static loading, particularly when, as in most modern means of transport, jolting is a compounding factor.

5.7. Pharmacotherapy

Since the main focus of this book is on dysfunctions of the locomotor system, it will be understood that pharmacotherapy can be effective only within certain limits. It is hardly likely that a restricted joint, an immobile fascia, or faulty motor patterns related to breathing or to carrying loads will respond to pharmacological correction. On the other hand, it is clear that disturbed function in itself is not synonymous with disease and pain. It is only with the onset of reflex changes, which are felt to be painful, that the patient will report symptoms. Then it is possible to employ pharmacological means to reduce the intensity of the reaction to nociceptive stimulation. Moreover, the pain threshold is a major factor and this can be influenced by pharmacotherapy.

It is therefore sometimes useful to prescribe medicines that lower the response of the autonomic nervous system; in particular, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are suitable for this purpose. It is important to issue warnings concerning the misuse/abuse of all types of analgesics in the setting of chronic pain. Dependence may develop and it is no coincidence that reduction of the analgesic dose is often the first step taken when patients are admitted to pain clinics.

Analgesics are frequently combined with muscle relaxants, and a great many combination products are available. Prescription of these products can be beneficial only in cases where general muscle tension has been demonstrated. However, the most commonly encountered patient category comprises constitutionally hypermobile individuals suffering from localized painful muscle tension. In such patients the combination of analgesics and muscle relaxants can serve not only to increase hypermobility and poor coordination, but also to complicate specific rehabilitation because fine muscle control tends to deteriorate.

The most rewarding effects of pharmacotherapy are achieved where patients with locomotor pain and suffering from masked depression are treated with mild antidepressants – a scenario that is not at all uncommon.

As a rule, treatment with corticosteroids is not indicated in locomotor system dysfunctions. Local application of corticosteroids should also only ever be implemented in exceptional circumstances. Pain points on the periosteum and at tendon and ligament attachments, as well as muscle TrPs, can generally be treated successfully using relaxation and soft tissue techniques, and by needling and local anesthesia. Corticosteroids should be prescribed only if these physiological methods have failed. Their administration should be repeated only if they elicit some improvement at the first attempt. However, corticosteroids are suitable for use where inflammatory changes are present.

5.8. Surgery

If the patient’s clinical condition is due to disturbance of function alone, there should be no question of surgical intervention. However, disturbed function may be the consequence of

structural changes that necessitate surgery. This scenario is encountered most commonly in radicular syndromes and other disorders associated with intervertebral disk lesions. Conservative measures primarily aimed at restoring function are frequently successful here. It is therefore not always straightforward to decide when still to adopt a conservative approach or when to intervene surgically (see

Section 7.8.2). Spinal canal stenosis may also be a (contributing) cause of radicular compression or even of spinal cord compression.

Cauda equina syndrome, a condition characterized by acute bladder and bowel paralysis and rapidly progressive muscle weakness, constitutes an indication for emergency surgery. Instability, for example in progressive spondylolisthesis or following trauma, may also provide an indication for surgery. Instability due to odontoid abnormality may also be dangerous. It should be noted here that the conservative management of instability has become far more effective in recent years.

5.9. Lifestyle

Lifestyle questions probably play the

most important role of all in the context of treating and preventing dysfunctions in the locomotor system. Lifestyle issues have been left almost until last because they do not constitute a therapeutic method in the true sense of the word, and a separate chapter has been devoted to this subject (see

Chapter 8).

One of the most important tasks facing the practitioner during history taking is therefore to discover the potential sources of trouble in the patient’s daily routine so that warnings can be given to steer clear of harmful lifestyle habits. Indeed, if we succeed in detecting these important clues, we should already be able to give very useful advice after the first examination. However, if patients refuse to desist from a clearly harmful lifestyle, then any therapy offered is destined to fail.

5.10. The course of manipulative treatment

The clinical examination provides information about the entire locomotor system or, at least, all key regions. Only once the examination stage is complete is it possible to consider whether we are faced with a typical chain reaction pattern or with a set of individual disorders of dubious connection.

In the former, more typical scenario, treatment should be given to the link in the chain that appears to be most relevant. Then all findings must be checked again. Ideally, the chain reaction will no longer be present and it is then clear what home exercise needs to be assigned to the patient: for example, if the key link was in the foot, rehabilitation will focus on the foot dysfunction. If a secondary finding is diagnosed, for example a painfully restricted acromioclavicular joint, then this can also be treated. However, if the chosen link turns out to be wide of the mark, then an attempt should be made using another link in the chain. And this is by no means uncommon because the first attempt at treatment is frequently used for diagnostic purposes; the diagnostic process proper ends with the first intervention. It is not unusual for this intervention also to be selected on diagnostic grounds so as to confirm the importance of a particular finding – something that applies especially with active scars.

However, if no chain reaction pattern at all is detected, then the findings made should be treated, and if there is an effective form of self-treatment, then the patient’s home exercise can be assigned.

The first follow-up examination about two weeks later then assumes special importance. On that occasion the working hypothesis from the first examination will be either verified or found to require revision. Depending on the outcome of the follow-up examination, the subsequent rehabilitation plan will be continued or reviewed and modified. If the findings have definitely improved and the patient’s home exercise is clear, then the interval between further follow-up examinations can be increased. Even if the initial results are favorable, patients with a longer history of such problems should be followed up for longer – ideally for several months – because the natural course of dysfunctions tends to be chronic and relapsing.

If no improvement is reported at the first follow-up examination, the first question to ask the patient must be: Did your condition improve briefly or not at all? The first intervention sometimes produces a very marked but short-lived effect. The follow-up examination may reveal one of two fundamentally different situations:

1. The findings are unchanged. This means that treatment has produced no results or that there has been a rapid recurrence of the patient’s condition (which is not much better).

2. The original findings have been corrected but new factors are now producing similar symptoms.

In the latter case the condition may actually be regarded as having improved even if the patient does not feel any better. In the cervical region in particular, a highly characteristic pattern may develop in which lesions tend to migrate in a caudal direction until they disappear.

In the former case, however, we must ask ourselves whether the initial analysis was correct and whether we failed to identify the true cause. Alternatively, the underlying condition may be more serious than appeared at first sight and may in fact be caused by pathomorphological changes. A further reason may be that patients often perform their home exercise wrongly or skip it altogether, for example, a simple self-mobilization technique or relaxation of TrPs.

If, despite the failure of treatment, there is a continuing conviction that the original diagnosis was correct, then the treatment may be repeated once more. If initial improvement is again promptly followed by recurrence, then the underlying cause of this must be sought. A clinical finding will often be made in the corresponding segment; in the thoracic outlet syndrome this is almost always reflected in clavicular breathing (i.e. lifting of the thorax during inhalation), with poor stabilization of the trunk, which then needs to be corrected.

However, the dysfunctions themselves can also be extremely complicated and multiple chain reaction patterns may be present, each one competing with the others. In such cases rapid results are unlikely and the patient will need to be monitored for a prolonged period. Chronic recurrent conditions such as migraine are routinely associated with dysfunctions of the locomotor system and tend to improve once these dysfunctions are treated. However, they may recur after a relatively long interval, and then the patient will need to be treated again.

Where manipulation was discussed in a preventive context (see Section

5.4), this should also be understood to include the prevention of recurrence: rehabilitation, which regularly follows on from our treatment, with patients themselves playing an ever-increasing role, is truly synonymous with the prevention of recurrence.

5.11. Conclusions

The ability correctly to establish whether or not a particular therapeutic intervention is indicated is the practical result of the pathophysiological thinking outlined in the theoretical sections of this book.

Because the patient’s symptoms are usually the result of many individual factors, the chief task of the practitioner is to single out on each occasion the factor that currently appears to be the most important and also the most accessible to treatment. In this regard the recognition of characteristic chains of dysfunctions has done much to define this process more precisely.

If we are successful at the patient’s initial visit, then a different therapeutic approach will quite likely be required when we next see the patient. Our aim is not constantly to promote one particular type of therapy but to normalize function and hence to relieve the patient’s symptoms. To do this we select the method that appears to be most advantageous. Such a strategy makes it difficult to determine which method has been most effective: manipulation, remedial exercise, or needling of a pain point. It would not be easy to justify the indication for further manipulation if movement restriction is no longer present, or for continuing to needle a pain point if this can no longer be detected. It therefore becomes difficult to determine statistically which method was most successful.

If a patient with acute appendicitis is cured and remains symptom-free after removal of the inflamed organ, the surgeon does not have to provide statistical proof that surgery was indicated. If a pain point or TrPs disappear after PIR, RI or needling in a patient with locomotor system dysfunction, or if a patient has learned how to normalize respiration and does not slip back into clavicular breathing (lifting the thorax during inhalation), then something has been achieved even if other lesions which still cause symptoms have yet to be treated.

This approach may seem rather unusual and complex, but it is consistent with the multifactorial nature of locomotor system dysfunction. It also precludes a monotonous, routine modus operandi characterized by a propensity for series of injections, repeated manipulation of a spinal segment, or the courses of electrotherapy so beloved of physiotherapists. The journey is a demanding one, but the effort involved is worthwhile both for the patient’s well-being and for refining the practitioner’s skills.