Incidentally Discovered Mass Lesions (Case 35)

Tami Berry MD Joseph J. Muscato MD

Case: A 42-year-old woman presented to her family physician with right lower quadrant discomfort of 2 days’ duration and was sent for a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis to “rule out appendicitis.” The CT scan revealed a normal appendix and no acute abnormality. The patient’s acute problem was self-limited, and she felt better the following day. However, the radiologist noted an “incidental finding,” and the family physician was promptly notified.

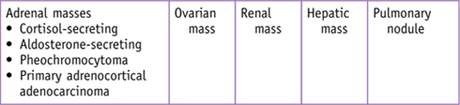

Differential Diagnosis

An incidentally discovered mass, or “incidentaloma,” will be experienced by every physician, both during training and during practice. The unsuspected mass that appears on imaging done for some other purpose can present a great conundrum for clinicians. As our population ages and both the frequency and resolution of radiologic imagery increase, there will consequently be more incidental mass findings. Clinicians must be prepared to manage these safely and effectively. The focus of evaluation is a balance of minimizing untoward stress or risk to the patient without missing something important that requires additional diagnostic evaluation.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

History and Physical Examination

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Adrenal Mass |

|

|

Pφ |

An adrenal “incidentaloma” is an adrenal mass > 1 cm in size that is discovered on radiologic imaging performed for reasons unrelated to the adrenal glands. |

|

TP |

Prevalence of an incidental adrenal mass found on abdominal CT imaging is 4% and in those aged ≥ 70 years is ∼7%. A compelling theory is that as people age there is increased likelihood of undergoing imaging and that the effects of local ischemia and atrophy lead to the development of cortical nodules or lesions. |

|

Dx |

Three questions should be investigated when evaluating an incidental adrenal mass: (1) Is the tumor active or functional? (2) Does the radiologic phenotype suggest malignancy? (3) Is there a history of a previous malignant lesion? FNA of the mass is recommended only in patients with suspicious radiologic phenotypic malignant features in the background of a prior oncologic process. FNA is also reasonable in patients refusing the recommendation for surgery, if the findings would alter management. FNA should proceed only after a pheochromocytoma has been ruled out, as hypertensive crisis and physiologic collapse may occur. |

|

Tx |

If any of the above diagnostic questions can be answered affirmatively, then a multidisciplinary approach is prudent, inclusive of an endocrinologist, surgeon, and medical oncologist. Refer to the following Clinical Entities on specific workup for hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, pheochromocytoma, and primary adrenocortical adenocarcinoma. Excess production of androgen or sex hormones is rarely asymptomatic and is not included in our discussion on incidental adrenal masses. Incidental adrenal lesions that are inactive and measuring over 4–6 cm warrant both radiologic and biochemical follow-up. Radiologic follow-up is fashioned to elicit whether the lesion is either dormant or rapidly proliferating; radiologic evaluations are recommended at 6-, 12-, and 24-month intervals. Annual biochemical assays, over a 5-year duration, are warranted for any nonfunctional adrenal mass measuring over 4–6 cm because there is a positive relationship between adrenal mass size and hormonal functionality. See Cecil Essentials 67. |

|

Cortisol-Secreting Adrenal Mass |

|

|

Pφ |

These lesions display autonomous glucocorticoid production and can be termed subclinical hypercortisolism (SCS) when the patient is asymptomatic or lacks the signs and symptoms of the Cushing syndrome. |

|

TP |

SCS is the most common biochemical abnormality detected in patients with an adrenal incidentaloma (∼9%) and can be accompanied by arterial hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance, and osteoporosis. |

|

An overnight 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test is done to screen for elevated cortisol levels in patients with suspected Cushing syndrome or SCS; a serum cortisol > 5 µg/dL after a 1-mg (low-dose) dexamethasone suppression test is considered positive (specificity 91%). If the screening test is positive, then confirmatory testing is warranted. This can be done with measurement of a 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC), midnight salivary cortisol, or a 48-hour 2-mg (high-dose) dexamethasone suppression test. |

|

|

Tx |

Medical therapy remains the mainstay of treatment. Surgical adrenalectomy is reserved for patients who are young (<40 years) and those with recent onset or worsening hypertension, glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, obesity, or osteoporosis. See Cecil Essentials 67. |

|

Aldosterone-Secreting Adrenal Mass |

|

|

Pφ |

Almost 1% of incidental adrenal masses are aldosterone-secreting adenomas, warranting biochemical evaluation in those with hypertension or other signs or symptoms consistent with autonomous aldosterone production. |

|

TP |

Patients with hypertension should undergo evaluation for hyperaldosteronism. In those with hypokalemia and mild hypernatremia, you may elicit a history of nocturia, polyuria, muscle cramping, and palpitations. |

|

Dx |

Measure the ambulatory morning plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) to plasma renin activity (PRA) ratio while the patient is upright. A PAC/PRA ratio > 20 is consistent with hyperaldosteronism (note: spironolactone and mineralocorticoid antagonists can result in false positive results). A positive screen is followed with confirmatory measurement of mineralocorticoid secretory autonomy with oral sodium loading, IV saline infusion, or a fludrocortisone suppression test. |

|

Tx |

Any lesion autonomously producing aldosterone should be referred for surgical removal. See Cecil Essentials 13, 67. |

|

Pφ |

Pheochromocytoma is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. |

|

TP |

History may include episodic (paroxysmal) rapid heart rate, tremor, headache, or diaphoresis. These episodes may be precipitated by anxiety, extreme postural changes, or medications (metoclopramide and anesthetic agents). |

|

Dx |

Initial evaluation should include measurement of plasma free metanephrines (sensitivity 98% and specificity 92%), and/or 24-hour total urinary metanephrines and fractionated catecholamines. A total plasma catecholamine of at least 2000 pg/mL is diagnostic of a pheochromocytoma. Generally a positive plasma fractionated metanephrine test deserves confirmation with either urinary fractionated metanephrines or a clonidine suppression test. When plasma free metanephrines, 24-hour urinary metanephrines, and fractionated catecholamines are elevated, the sensitivity is 100% and specificity 96.7%, with a negative predictive value of 100%. False positive results can occur in patients with congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, acute alcohol or clonidine withdrawal, cocaine use, or use of medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, phenoxybenzamine, bromocriptine, labetalol, and α1-adrenergic receptor blockers. |

|

Tx |

The mainstay of treatment for pheochromocytoma is surgical resection after several weeks of α-adrenergic blockade. See Cecil Essentials 13, 67. |

|

Primary Adrenocortical Adenocarcinoma |

|

|

Pφ |

Primary adrenocortical adenocarcinoma is found in 4.7% of patients and is metastatic in 2.5%. The prognosis is very poor, with mean survival at the time of diagnosis of only 18 months. |

|

TP |

There may be a history of some degree of discomfort secondary to mass effect or other vague symptoms related to secretion of any the adrenals’ hormonally active substances. Patients may have signs of osteopenia, osteoporosis, hypertension, glucose intolerance, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and leukocytosis or lymphopenia. Only 50% to 60% of adrenocortical adenocarcinomas are hormonally active. Furthermore, patients with hormonally inactive adrenocortical adenocarcinomas rarely present with weight loss, fever, or anorexia, or other symptoms of back or abdominal pain. |

|

The mass size and radiologic appearance are the two major predictors of malignant disease. A diameter > 4 cm is consistent with an adrenocortical carcinoma with a sensitivity of 90% (specificity only 24%). Risk of malignancy rises with increasing size of adrenal masses: those <4 cm confer 2% risk for malignant potential, 4–6 cm 6% risk for malignant potential, and >6 cm a 25% risk for malignant potential. Based on size alone, surgical removal is advocated for adrenal masses > 4–6 cm. Once adrenocortical carcinoma is suspected, size matters even more, because the smaller the lesion at the time of diagnosis, the lower will be the tumor stage, which correlates with a better overall prognosis. |

|

|

Tx |

Referral to both medical and surgical oncologists is appropriate. See Cecil Essentials 67. |

|

Ovarian Mass |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Pφ |

Any adnexal mass identified by a primary-care physician or gynecologist should be considered potentially malignant in patients in any age group. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

TP |

In terms of gynecologic cancer, ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death. In 2007 an estimated 22,500 women were newly diagnosed and there were more than 15,000 deaths. Mortality rises with advanced stage; the 5-year survival in those with stage I cancer approaches 90%, while the 5-year survival in those with stage III or IV is between 30% and 55%. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Dx |

Most incidentally discovered adnexal masses are benign, especially those that are unilocular cystic masses in premenopausal or perimenopausal women. Cystic lesions measuring >5–6 cm should be followed up radiologically in the premenopausal age group, as they are at risk of torsion. Referral to a gynecologic oncologist is recommended when complex cysts of any size are found in postmenopausal women (risk of malignancy 3%). Tumor volume doubling time for ovarian cancer is <3 months; thus, repeat imaging (ultrasound or MRI) should occur in 6 weeks on any lesions with solid components or any lesion in postmenopausal women. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Tx |

Operative indications and referral are warranted in patients who are symptomatic and those who display increasing size of the lesion over time. See Cecil Essentials 57. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Renal Mass |

|

|

Pφ |

Incidental renal tumors have emerged as a new clinical entity with modern imaging. Small renal masses measure <4 cm and enhance on imaging. Renal masses are covered in greater detail in Chapter 25. |

|

TP |

The frequency of small renal masses has risen quite steeply. A recent review by the US National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) shows that the proportion of tumors measuring <4 cm increased by >10% between 1993 and 2004. |

|

Dx |

There are no concrete guidelines on evaluation, management, and surveillance of small renal masses. The consensus is that elderly or infirm patients, with an expected short life expectancy, can undergo surveillance with imaging every 6–12 months. Several studies have supported a positive correlation between renal cell tumor growth and increasing malignancy and higher tumor grade. Percutaneous biopsy (PCB) has been utilized to distinguish benign from malignant lesions, but this falls short on accuracy (20% remain indeterminate) and thus should be used only if the result will change management. |

|

Pathologic grading is traditionally done at the time of surgical removal. Surgical excision has been the mainstay of treatment for renal masses especially in those under the age of 70 years with a significant life expectancy. Young, healthy individuals with lesions that are >1 cm generally are referred for surgical removal. Treatment options include radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation, although long-term data on efficacy are not yet available. Nephron-sparing surgery (NSS) is appropriate for many patients. See Cecil Essentials 30, 57. |

|

|

Hepatic Mass |

|

|

Pφ |

Liver lesions can be quite common. Most of them will be benign and appear as a simple cyst, hemangioma, focal fat, or focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). Incidental liver masses are challenging in patients with cirrhosis, fibrosis, and hemochromatosis, as there is a slightly higher propensity for malignant potential. |

|

TP |

These lesions are discovered at the time of right upper quadrant ultrasound or upon CT performed for reasons other than those related to liver abnormalities. |

|

Dx |

Workup of incidental liver lesions follows an algorithm based on the clinical and radiologic pictures correlating positively with malignant potential. Classic benign lesions contain fat or serous contents (simple cyst, hemangioma, FNH). Patients with a previous history or risk factors for hepatic malignancy warrant MRI with contrast, or helical CT with contrast, including delayed portal venous phases. Patients with lesions that correlate both clinically and radiologically with malignancy should be evaluated with serum tumor markers and/or percutaneous core biopsy. |

|

Tx |

Malignant confirmation warrants referral to both surgical and medical oncologists for directed treatment and management. |

|

Solitary Pulmonary Nodule |

|

|

Pφ |

A solitary pulmonary nodule is an approximately round lesion that is between 1 and 3 cm in diameter and completely surrounded by pulmonary parenchyma. When warranted, workup is critical because of the high mortality rate (85%) in those with lung cancer. Pulmonary nodule is covered in greater detail in Chapter 17. |

|

Concern for malignant potential should be raised in those with a social history of smoking (total pack-years is directly proportional to incidence of cancer). Other risk factors include prior malignancy (testicular, melanoma, sarcoma, or colon), pulmonary fibrosis, and HIV infection. |

|

|

Dx |

Stable radiologic findings over a 2-year period support a benign etiology. Reviewing old images is prudent and may negate further workup. Lesions with spiculated margins and calcifications that are stippled, eccentric, diffuse, or amorphous warrant further workup with either FNA or core biopsy (if lymphoma is suspected). CT with IV contrast that demonstrates nodule enhancement <15 HU is strongly indicative of a benign etiology (positive predictive value, ∼99%). An excellent prediction model is available at http://www.chestx-ray.com. |

|

Tx |

If malignant features are present, staging must be performed to determine the appropriate treatment. See Cecil Essentials 24. |

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Adrenal lesion frequency: a prospective, cross-sectional CT study in a defined region, including systematic re-evaluation

Authors

Hammarstedt L, Muth A, Wangberg B, et al.; on behalf of the Adrenal Study Group of Western Sweden

Institution

Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Southern Alvsborg Hospital, Kungalv Hospital, Northern Alvsborg Hospital

Reference

Acta Radiol 2010;10:1149–1156

Problem

The investigative goal was to prospectively estimate and validate the prevalence of detected adrenal incidentalomas in patients undergoing abdominal CT evaluations in the clinical setting.

Intervention

During their 18-month collection period, 30,000 CT scans were performed in western Sweden (population 1.6 million). Initial reported frequency was compared to the frequency of detection on systematic re-evaluation by blinded interobserver assessments performed by experienced radiologists.

Comparison/control (quality of evidence)

Approximately 30,000 CT scans were performed in western Sweden during the 18-month collection period. The initial reportable frequency of adrenal lesions was 0.9% (range 0%–2.4% among hospitals). The systematic re-evaluation of 3801 randomly selected cases showed a mean frequency of 4.5% (range 1.8%–7.1% among hospitals). On the systematic re-evaluation, 177 cases of incidental adrenal lesions were found; 47% of these had not been reported by the radiology department.

Outcome/effect

This study concludes that adrenal lesions are under-reported in clinical practice.

Historical significance/comments

The results of this study imply that the medical community has largely under-recognized the incidence of adrenal lesions that are found on CT imaging. Consequently, we also underappreciate the prevalence of adrenal masses. This may have broader implications on the clinical management approach when we acknowledge that much of the natural history of incidental adrenal masses may be largely unknown.

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Physician-Patient Joint Decision Making Follows the Model of Patient-Centered Care

A discussion about an unexpected finding is a challenge. The finding of a potentially serious, but asymptomatic, lesion requires a straightforward and gentle delivery. Your words should reassure the patient that many of these findings are not serious, but you should outline whatever further evaluation may be necessary. Choosing the right language can be difficult. Remember that the process of shared, informed decision making is the essence of patient-centered care and guides physicians and patients under conditions of uncertainty and risk. Under this model, the physician provides information of clinical probability (based on thorough history, physical examination, and review of pertinent studies), weighing the risks and benefits of different management strategies. Ultimately the physician and patient identify the management option that best aligns with the patient’s values and elicits the most appropriate course of action.

Uphold the Primacy of Patient Welfare

Primum non nocere. Above all do no harm. The finding of an incidental mass on a radiologic study engenders concern in the patient. It is often necessary to be clear with patients about the need for careful radiologic follow-up evaluation, as some of these findings, when properly monitored, will lead to better outcomes. However, these potential benefits must be balanced with the risks of radiation exposure. Overly frequent imaging carries the risks of cumulative radiation exposure, which has potential for long-term negative consequences. In these circumstances, physicians should adhere to evidence-based recommendations to ensure the greatest benefit, while minimizing risk to the patient.

Systems-Based Practice

Be Mindful of the Benefits and Risks of Testing

The frequency of incidentally detected adrenal lesions will grow as the population ages and more refined investigative tools are utilized for assessment. Adrenal lesions are now probably underreported in all clinical settings. Managing an adrenal lesion should be approached by characterizing the lesion to determine whether it is probably malignant and by assessing possible hormonal production. Most adrenal lesions are benign and hormonally inactive, but reliable identification and reporting in the primary radiologic investigation is a prerequisite for further characterization and management. Given the widely publicized concerns about excessive radiation exposure related to CT scans and other imaging modalities, compliance with guidelines to minimize radiation exposure is important in the follow-up of these lesions.

Suggested Readings

Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM, et al. Managing incidental findings on abdominal CT: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol 2010;7:754–773.

Hammarstedt L, Muth A, Wangberg B, et al., on behalf of the Adrenal Study Group of Western Sweden. Adrenal lesion frequency: a prospective, cross-sectional CT study in a defined region, including systematic re-evaluation. Acta Radiol 2010;10:1149–1156.

Mues AC, Landman J. Small renal masses: current concepts regarding the natural history and reflections on the American Urological Association guidelines. Curr Opin Urol 2010;20:105–110.

Patard JJ. Incidental renal tumours. Curr Opin Urol 2009;19:454–458.

Tien L, Giede C. Initial evaluation and referral guidelines for management of pelvic/ovarian masses. Joint SOGC/GOC/SCC Clinical Practice Guideline No. 230, July 2009.

Winer-Muram HT. The solitary pulmonary nodule. Radiology 2006;239:34–49.

Zieger MA, Thompson GB, Quan-Yang D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons (AACE/AAES) medical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentalomas. Endocrine Pract 2009;15(Suppl 1):1–20.