Advances in the Surgical Management of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is a mesenchymal tumor that typically arises from the alimentary tract [1]. In the past, these tumors were classified as leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, or leiomyoblastomas. Only recently has it become evident that GIST is a separate entity and the most common sarcoma of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, with an annual incidence in the United States of approximately 5000 [2].

GIST is believed to arise from the KIT (CD117)-positive interstitial cell of Cajal [3], the pacemaker cell of the GI tract. Approximately 85% of GISTs harbor an activating KIT mutation, which leads to constitutive activation of KIT and its tyrosine kinase function [4]. KIT is involved in many cellular functions, including cell differentiation, growth, and survival. Binding of KIT to its ligand leads to dimerization and subsequent autophosphorylation of KIT, which initiates a cascade of intracellular signaling leading to adhesion, differentiation, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. About 3% to 5% of GISTs instead carry a mutation in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα) gene [5]. Interestingly, 10% to 15% of the tumors contain the wild-type forms of the KIT and PDGFRα proto-oncogenes, yet still overexpress KIT [6].

In 2001, Joensuu and colleagues [7] published their experience with imatinib mesylate (Gleevec; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland), a small-molecule tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, in a single patient with metastatic GIST. Dramatic regression of the disease was evident on serial imaging, and thus began the paradigm shift in the treatment of GIST. At present, with an approximately 80% response rate to imatinib, compared with a dismal 5% response to conventional cytotoxic agents, the median survival in patients with metastatic GIST has increased to 5 years from 15 months in the era before tyrosine kinase inhibitors [8]. Molecular targeted therapy has truly revolutionized the treatment of patients with metastatic GIST and provided an opportunity for adjuvant and primary systemic therapy for localized and recurrent disease.

Clinical presentation

GISTs demonstrate a fairly equal distribution between men and women; however, some literature suggest that there is a slight male predominance [9]. Although GIST has been reported in patients of all ages, including children, most people affected by the disease are between 40 and 80 years old at the time of diagnosis, with a median age of 60 years. Most GISTs are sporadic. Nonetheless, there are several case reports of familial germline mutations in the KIT or PDGFRα proto-oncogenes [10,11].

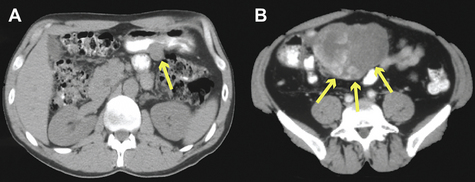

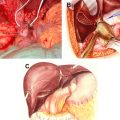

Approximately 60% of GISTs occur in the stomach, whereas 30% of cases are found in the small intestine, 5% in the rectum, and 5% in the esophagus (Fig. 1) [9]. Rarely, they can also develop in the omentum, mesentery, pancreas, or other retroperitoneal organs [12].

Fig. 1 (A) A large exophytic gastric GIST. (B) GIST emanating from the anti-mesenteric border of jejunum.

Most (70%) patients diagnosed with GIST have vague symptoms, such as abdominal pain, GI bleeding from a mucosal erosion, or an abdominal mass [13]. Ten percent of the cases are detected only at the time of autopsy. Intestinal obstruction from GISTs is rare, because GISTs behave like other sarcomas and usually displace rather than invade adjacent structures. Occasionally, however, they may serve as lead points for intussusception. Patients with esophageal or duodenal GIST may rarely present with dysphagia or jaundice, respectively.

Diagnosis and evaluation

Because of the infrequency of GIST, the disease is rarely suspected before the time of surgery. A high index of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis. The best radiologic study to characterize a mass suspicious for GIST, as well as to evaluate the extent of the disease, is a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis. Metastases to the lungs or other extra-abdominal locations are usually observed only in advanced cases. On a CT scan, GISTs typically appear as hyperdense, enhancing masses, closely associated with the stomach or small intestine (Fig. 2). The liver and peritoneal surface are the most common sites of metastatic disease. Lymph node metastases are rare, except in the pediatric population [14]. Children are also more likely to present with multifocal disease and lack a KIT or PDGFRα mutation. GISTs may appear heterogeneous because of central necrosis or intratumoral hemorrhage. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful in rectal GIST. Positron emission tomography (PET) is not specific enough for the diagnosis of GIST, but can be used to monitor the clinical response to imatinib treatment, although it is rarely needed. On endoscopy, GIST appears as a submucosal mass, since it originates from the bowel wall and not the mucosa. This can be confirmed via endoscopic ultrasound. Often, however, endoscopic evaluation is unnecessary.

Recent studies have shown that endoscopic fine-needle aspiration (FNA) for the diagnosis of GIST has a sensitivity as high as 80% [15]; however, preoperative tissue diagnosis is usually not required unless the diagnosis is in doubt. A biopsy is recommended for metastatic disease or if neoadjuvant imatinib is under consideration.

Prognostic factors

In GIST, a gain-of-function mutation in KIT (85%) leads to constitutive activation of KIT and its tyrosine kinase function. Several mutations have been described, the most common being KIT exon 11 (70%) and exon 9 (10%) [4,6]. As mentioned previously, 3% to 5% of GISTs harbor a mutation in the PDGFRα proto-oncogene, whereas 10% to 15% of tumors carry wild-type alleles of KIT and PDGFRα, yet overexpress KIT. GISTs may also be positive for CD34 (60%–70%), smooth-muscle actin (SMA; 30%–40%), S-100 protein (5%), and, rarely, desmin [16]. Unlike other GI malignancies, the behavior of GIST is difficult to predict based on histopathology alone. Although the best indicator of malignancy is the confirmation of metastatic disease, 3 characteristics have been shown to predict how GISTs will behave: size, mitotic rate, and tumor location [17]. In general, GISTs of 10 cm or larger are more likely to recur. Mitotic index is the dominant predictor of recurrence, as tumors with at least 5 mitoses per 50 high-powered fields (HPFs) are 15 times more likely to recur than those with fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. Also, GISTs originating in the small intestine exhibit a more aggressive behavior than those of similar size and mitotic index originating in the stomach. Importantly, neither small size nor low mitotic rate excludes the potential for malignant behavior. Patients with either a KIT exon 9 mutation or KIT exon 11 deletion involving amino acid W557 and/or K558 experience a higher rate of recurrence, whereas point mutations and insertions of KIT exon 11 confer a more favorable prognosis.

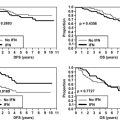

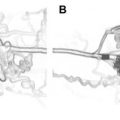

Recently, we developed a GIST prognostic nomogram based on tumor size (cm), location of disease (stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, or other), and mitotic index (<5 or ≥5 mitoses per 50 HPFs) from 127 patients treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) between 1983 and 2002 [18]. It predicts recurrence-free survival at 2 and 5 years after complete surgical resection of localized primary GIST (Fig. 3). We validated the nomogram using a series of patients from the Mayo Clinic and another series from the Spanish National Registry, and showed better predictive accuracy than those of 2 commonly used staging systems developed at the National Institutes of Health GIST workshop and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology–Miettinen staging system [19]. Including the presence or type of KIT or PDGFRα mutation did not improve the discriminatory ability, although this may be because of limited sample sizes.

Treatment

Primary GIST

For patients with primary localized GIST, surgical extirpation remains the only chance for cure. The goal of the operation is to achieve a negative microscopic margin (R0 resection) with an intact tumor pseudocapsule. At exploration, careful examination of the liver and peritoneal surfaces for previously undetectable metastatic disease should be performed. Care should be exercised to avoid excessive tumor manipulation, which can disrupt what may be a friable tumor and lead to bleeding and intraperitoneal dissemination. Resection can usually be accomplished with only a wedge resection of the stomach or a segmental resection of the small bowel. In a series of 140 patients with gastric GISTs, 68% underwent a wedge resection, 28% required a partial gastrectomy, and only 4% needed a total gastrectomy [20].

Extensive surgery is occasionally required for larger or poorly positioned tumors, such as those near the gastroesophageal junction, periampullary region, or distal rectum. Because GIST does not typically exhibit an intramural spreading behavior, wide margins of resection are not necessary and have not been associated with better prognosis, although every effort should be made to obtain gross negative margins [9]. Re-excision of disease in patients who underwent an inadvertent R1 resection should be considered on a case-by-case basis, because of the lack of evidence supporting a clear association between microscopically positive margins and poorer survival outcomes. Laparoscopic resection of primary GIST may be considered by surgeons experienced in this approach. Standard oncologic principles still apply. A laparoscopic R1 resection should not be accepted if laparotomy guarantees an R0 resection. GISTs measuring 1.0 to 8.5 cm in size have been successfully treated with minimally invasive techniques [21]. Because GISTs rarely metastasize to lymph nodes, formal lymphadenectomy is not necessary unless locoregional lymph nodes are enlarged. When adherence to adjacent organs is identified, an en bloc resection is favored.

Complete gross resection is possible in 85% of patients with primary, localized GISTs. Nevertheless, without any further treatment, at least 50% of patients develop tumor recurrence and 5-year survival rate is approximately 50% [9,22]. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for the treatment of GIST has generally not been recommended because of dismal response rates of traditional chemotherapeutic agents [23]. Radiotherapy is also of limited value, due to the location of the tumors and the limit this places on the doses that can be safely used. Radiation, however, may be useful for some pelvic GISTs. Treatments such as hepatic artery embolization and debulking surgery followed by intraperitoneal chemotherapy have also been investigated but with relatively limited results [24,25].

The application of imatinib mesylate in the treatment of GIST reflects a major advance in the therapy of solid tumors with specific molecular targeting and has become the first-line medical treatment for metastatic, unresectable, or recurrent GIST [26]. The landmark case report of Joensuu and colleagues [7] prompted Phase II and III clinical trials to confirm the efficacy of imatinib in the treatment of metastatic or unresectable GIST. In 2002, Demetri and colleagues [27] published the results of a Phase II trial establishing that 400 mg/d or 600 mg/d of imatinib can lead to sustained objective response in patients with metastatic or advanced unresectable GIST. The initial median follow-up was 6 months and more than 80% of patients showed either disease regression or stabilization. A subsequent long-term analysis demonstrated a median survival of 57 months, as compared with 15 to 20 months for historical controls [8]. Phase III trials confirmed the effectiveness of imatinib as primary systemic treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic GIST [28,29].

Adjuvant imatinib

Because 50% of patients with complete resection of their primary localized GIST develop recurrent disease, and given the paucity of effective chemotherapeutic agents, the use of adjuvant imatinib after complete resection of primary GIST was evaluated in a Phase II trial led by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG; ACOSOG Z9000) [30]. The study analyzed the effects of adjuvant imatinib at a dosage of 400 mg/d for 1 year after complete resection of primary GIST in 107 high-risk patients. High risk was defined as a tumor size larger than 10 cm, intraperitoneal tumor rupture or hemorrhage, or multifocal (<5) tumors. At a median follow-up of 4 years, the 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year overall survival rates were 99%, 97%, and 97%, respectively, whereas the recurrence-free survival rates were 94%, 73%, and 61%, respectively. Data from this trial established that imatinib is well tolerated in the adjuvant setting, prolongs recurrence-free survival, and is associated with improved overall survival when compared with historical controls.

In 2009, a Phase III ACOSOG intergroup trial (Z9001) was published [31]. Patients were randomized to imatinib 400 mg/d (n = 359) or placebo (n = 354) for 1 year after undergoing complete resection of their localized, primary GIST (≥3 cm tumor size). Accrual to the trial was halted based on the results of a planned interim analysis of 644 evaluable patients. At median follow-up time of 19.7 months, 30 (8%) patients in the imatinib group and 70 (20%) patients in the placebo arm had developed recurrent disease or had died. Patients assigned to the imatinib arm had a 1-year recurrence-free survival of 98%, compared with 83% in the placebo arm. No difference in overall survival between the 2 treatment arms was noted. However, longer follow-up of the cohort is needed to determine the impact of adjuvant imatinib on overall survival.

On the basis of the Phase III ACOSOG intergroup trial, the Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency approved the use of adjuvant imatinib in 2008 and 2009, respectively. However, because of the high financial cost of treatment and the potential side effects of imatinib, the ability to measure the risk of recurrence for an individual patient is desirable. We expect that the prognostic nomogram developed by Gold and colleagues [18] can be used to help identify which patients will benefit from adjuvant therapy.

Neoadjuvant imatinib

Neoadjuvant imatinib is particularly attractive for patients with large or poorly localized primary tumors that would otherwise require extensive surgery or sacrifice of a large amount of normal tissue. Neoadjuvant therapy with the intent of cytoreduction may convert the surgical treatment of a rectal GIST from an abdominoperineal resection to a low anterior resection. Early results of a nonrandomized Phase II trial testing neoadjuvant/adjuvant imatinib mesylate for primary advanced and potentially operable metastatic/recurrent GIST, led by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG), were recently published [32]. Sixty-three patients entered the trial; 52 were analyzed with 30 patients having primary advanced GIST (Group A; size ≥5 cm) and 22 patients with metastatic/recurrent disease (Group B; size ≥2 cm). Results showed that preoperative imatinib (600 mg/d for 8–12 weeks) followed by postoperative imatinib (600 mg/d for 24 months) for patients with advanced primary or potentially operable metastatic/recurrent GIST is well tolerated, with minimal toxicity and postsurgical complications. Response (as measured by Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors [RECIST]) in Group A was 7.0% partial, 83.0% stable, and 10.0% unknown, and in Group B response was 4.5% partial, 91.0% stable, and 4.5% progression. The 2-year progression-free survival was 83% in Group A and 77% in Group B, with an estimated overall survival of 93% in Group A and 91% in Group B.

As there is now effective treatment for recurrent or metastatic GIST, the 2009 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast every 3 to 6 months during the first 3 to 5 postoperative years and perhaps yearly thereafter [2].

Recurrent GIST

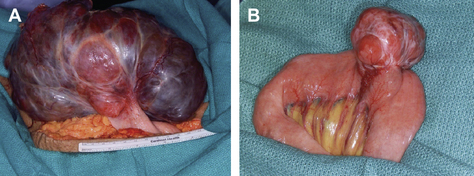

Historically, most patients undergoing complete resection of their primary GIST will develop tumor recurrence [9]. The median time to recurrence is reported to range from 18 to 24 months. At the time of recurrence, approximately two-thirds of the patients have liver involvement and half present with peritoneal disease. Extra-abdominal metastasis to lung or bone may develop as the disease progresses. Surgery alone has limited efficacy in recurrent or metastatic GIST. Excision of peritoneal disease is usually followed by subsequent recurrence. Although liver metastases are usually multifocal, approximately 26% of the patients are still candidates for resection [33]. However, essentially all of the patients developed recurrent disease after hepatic resection in the era before tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

In patients with metastatic or recurrent GIST, imatinib is reported to produce a partial tumor response in 50% of patients and stable disease in approximately 30%. Remarkably, the 2-year survival of patients with metastatic disease is now reported to be approximately 70%, and median survival has improved to nearly 5 years [27,28,34]. By contrast, before the introduction of imatinib, the median survival after surgical resection of recurrent GIST was only 15 months.

Current recommendations for a patient with locally advanced or recurrent metastatic disease are to start imatinib at 400 mg daily [2]. When unequivocal progression is observed, the dosage can be increased incrementally up to 800 mg daily, as permitted by toxicity. However, the success of this strategy appears to be limited, except in tumors with primary mutations in KIT exon 9 (10% of GISTs). Because imatinib rarely induces a complete response and the median time to progression with imatinib therapy is fewer than 24 months, a multimodal approach using surgical resection in conjunction with imatinib therapy to treat recurrent metastatic GIST is highly desirable. In a recent study from MSKCC [35], 40 patients with metastatic GIST were treated with imatinib for a median of 15 months before surgical resection. Based on preoperative serial radiologic imaging, patients who had stable or responsive disease on imatinib had a 2-year progression-free survival of 61% and 2-year overall survival of 100% after surgical resection. In contrast, patients who experienced focal resistance of their disease progressed at a median of 12 months postoperatively, with a 2-year overall survival of just 36%. Patients with multifocal resistant disease progressed postoperatively at a median of 3 months and experienced a 1-year overall survival of 36%. Based on these results, selected patients with metastatic GIST who have responsive disease or focal resistance to imatinib may benefit from resection. However, surgery is generally not recommended in patients with metastatic GIST and multifocal resistance. Similar results were observed by Gronchi and colleagues [36] in a study of 38 patients with advanced GIST who underwent surgery following a variable period of imatinib therapy. Additionally, Raut and colleagues [37] published their series of 69 patients with advanced GIST who underwent surgery and concluded that patients with advanced GIST exhibiting stable disease or minimal progression on kinase inhibitor therapy likely have prolonged overall survival after debulking procedures. Surgery is usually futile in patients with generalized progression of disease while on therapy, unless to provide symptomatic relief.

Our experience suggests that the risk of disease progression on imatinib therapy, and hence developing imatinib resistance, is proportional to the amount of residual viable GIST. Therefore, once maximal response to imatinib occurs (generally after 3–6 months of therapy), we evaluate patients with metastatic disease for complete resection. Imatinib therapy is continued postoperatively, unless precluded by toxicity, to delay or prevent subsequent disease recurrence, although the optimal duration of therapy is unknown [38]. The risk of interrupting imatinib therapy in patients with visible disease was clearly demonstrated in a recent study by the French Sarcoma Group. Eighty-one percent of patients with responsive or stable disease while on imatinib therapy experienced rapid disease progression when imatinib was stopped [39].

The success of imatinib in treating patients with GIST is defined by lack of disease progression, rather than shrinkage of existing tumors [40]. When metabolic and anatomic imaging are combined, GISTs that respond to molecular therapy may be stable in size but demonstrate areas of necrosis. When using these criteria, 12% of patients with GIST who are treated with imatinib demonstrate primary resistance, defined as progression within the first 6 months of imatinib treatment. Clinical studies have demonstrated that the location of mutations in the pathogenic kinase is an important factor in both treatment response and development of resistance to imatinib. Patients who experience primary resistance usually express both wild-type KIT and PDGFRα, or contain mutations in exon 9 of KIT or a D842V mutation in PDGFRα [41,42]. Secondary or late resistance therefore occurs in patients who have initially demonstrated stabilization of their disease for at least 6 months. Unfortunately, most patients who initially demonstrate a clinical response to imatinib will subsequently develop (secondary) resistance, as a result of additional point mutations in the KIT kinase domains [43,44]. Usually, most resistant GISTs with a secondary KIT mutation have a primary mutation in exon 11. The second site mutations are mainly substitutions involving exons 13, 14, and 17 of KIT, corresponding to the kinase domain.

There is general agreement that multifocal resistance to imatinib should be treated with another targeted agent such as sunitinib (Pfizer, New York, NY) [2,45], which has activity against KIT and PDGFRα, as well as the vascular endothelial cell growth factor receptor (VEGFR), fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3) receptor, and the RET receptor. Sunitinib may also have activity in GISTs harboring secondary KIT mutations [45]. In 2007, Demetri and colleagues [46] published their experience with sunitinib in 207 patients with advanced GIST who were resistant to or intolerant of previous treatment with imatinib. The median time to tumor progression was 27.3 weeks on sunitinib and 6.4 weeks on placebo. In a recent study by Raut and colleagues [47], the impact of surgery in 50 imatinib-resistant patients on second-line sunitinib therapy was evaluated. In contrast to imatinib-responsive patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery, response to sunitinib did not correlate with a better survival outcome. Incomplete resections were frequent (50%) and complication rates were high (54%), although not surprising, given the advanced nature of the disease and extensive surgical history of the cohort. The ideal candidate for surgery on sunitinib, thus, remains undefined.

Further understanding of the mechanisms of resistance to imatinib may allow for the delay or prevention of this phenomenon. Additionally, a number of other agents are currently in clinical trials and resistance to one drug may not preclude a therapeutic benefit from another [2]. A proposed algorithm for the treatment of primary and recurrent metastatic GIST is outlined in Fig. 4.

References

Disclosures: Ronald P. DeMatteo has served on advisory boards for Novartis and received honoraria.