Chapter 40 Immunocompromised Host

1 What is the initial approach to the immunocompromised host in the intensive care unit (ICU)?

The approach in the ICU setting relies on several factors:

High index of clinical suspicion: Immune-compromised hosts often have atypical presentations of infection. For example, patients with severe immunocompromise may lack fever or abscess formation.

High index of clinical suspicion: Immune-compromised hosts often have atypical presentations of infection. For example, patients with severe immunocompromise may lack fever or abscess formation.

Understanding of the host’s immune defect: Recognizing the deficient pathway (cell mediated vs. humoral) enables the physician to expand the differential diagnosis and has implications for empiric therapy.

Understanding of the host’s immune defect: Recognizing the deficient pathway (cell mediated vs. humoral) enables the physician to expand the differential diagnosis and has implications for empiric therapy.

Aggressive diagnostics: Blood work and cultures, imaging, bronchoscopy, and tissue biopsy, if indicated, are all essential in the initial work-up of a suspected infection.

Aggressive diagnostics: Blood work and cultures, imaging, bronchoscopy, and tissue biopsy, if indicated, are all essential in the initial work-up of a suspected infection.

Early appropriate antimicrobial therapy: This is key when dealing with infections in the immunocompromised patient.

Early appropriate antimicrobial therapy: This is key when dealing with infections in the immunocompromised patient.

2 What is the “net state of immunosuppression,” and why is it important?

Immunosuppressive medications. The degree of immunosuppression conferred by these medications will be influenced by their type, dose, and duration of therapy.

Immunosuppressive medications. The degree of immunosuppression conferred by these medications will be influenced by their type, dose, and duration of therapy.

Presence of leukopenia. Long-standing neutropenia carries a different risk of infection as compared with acute-onset neutropenia. For example, acute neutropenia conveys an increased risk of infections with gram-negative and enteric organisms. As the duration of neutropenia continues, these patients are at increasing risk for invasive fungal infections.

Presence of leukopenia. Long-standing neutropenia carries a different risk of infection as compared with acute-onset neutropenia. For example, acute neutropenia conveys an increased risk of infections with gram-negative and enteric organisms. As the duration of neutropenia continues, these patients are at increasing risk for invasive fungal infections.

Metabolic factors. Poor nutrition, hyperglycemia, and uremia all confer an increased risk for infection.

Metabolic factors. Poor nutrition, hyperglycemia, and uremia all confer an increased risk for infection.

Concurrent infection with immunomodulating viruses such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis B and C, human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6), and HIV. These infections can weaken the host’s defenses either by a low level of viral replication or by reducing the function of infected white blood cells. This leads to an increased risk for bacterial or fungal infection.

Concurrent infection with immunomodulating viruses such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis B and C, human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6), and HIV. These infections can weaken the host’s defenses either by a low level of viral replication or by reducing the function of infected white blood cells. This leads to an increased risk for bacterial or fungal infection.

Anatomic factors. The presence of obstructing tumors, stents, central venous catheters, and endotracheal tubes can affect a host’s risk for infection.

Anatomic factors. The presence of obstructing tumors, stents, central venous catheters, and endotracheal tubes can affect a host’s risk for infection.

3 How is immunosuppression measured?

Assessment can be based on the following:

Duration and level of neutropenia in those undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy are used to determine the risk of infection and need for empiric antibiotic therapy. For example, patients with a longer duration of absolute neutropenia have a greater risk for invasive fungal infection compared with patients with acute neutropenia.

Duration and level of neutropenia in those undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy are used to determine the risk of infection and need for empiric antibiotic therapy. For example, patients with a longer duration of absolute neutropenia have a greater risk for invasive fungal infection compared with patients with acute neutropenia.

CD4 cell count in patients with HIV is an accurate measure of their immune function. A patient with HIV who has an absolute CD4 count of 700/mm3 has a very different infection risk compared with someone whose CD4 counts are under 100/mm3.

CD4 cell count in patients with HIV is an accurate measure of their immune function. A patient with HIV who has an absolute CD4 count of 700/mm3 has a very different infection risk compared with someone whose CD4 counts are under 100/mm3.

Treatment, type, and duration of therapy in patients receiving immunosuppression after solid organ, stem cell, or bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Also, the type of transplant (matched or unmatched donor) may be important. Patients who undergo stem cell transplantation or BMT from an allogeneic human leukocyte antigen–identical sibling or matched unrelated donor are at greatest risk for infection because they may require more immunosuppression.

Treatment, type, and duration of therapy in patients receiving immunosuppression after solid organ, stem cell, or bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Also, the type of transplant (matched or unmatched donor) may be important. Patients who undergo stem cell transplantation or BMT from an allogeneic human leukocyte antigen–identical sibling or matched unrelated donor are at greatest risk for infection because they may require more immunosuppression.

4 Do certain immunosuppressive therapies carry a specific risk of infection?

| Agent | Mechanism of action | Associated risk of infection |

|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | Down-regulates lymphocyte and macrophage function Interferes with inflammatory response |

Long-term use—PCP, hepatitis B, bacterial, molds, mycobacterial disease Bolus use—CMV, BK virus nephropathy |

| Calcineurin inhibitors |

Bacterial and fungal infections

Decreases IL-2

Hepatitis B reactivation

Lymphoma

IL, Interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VZV, varicella-zoster virus.

* Immunosuppression is greater when used as a bolus for antirejection rather than when used as initial induction therapy.

Modified from Fishman JA, Issa NC: Infections in organ transplantation: risk factors and evolving patterns of infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am 24:273-283, 2010, and Danovitch G: Immunosuppressive medications and protocols for kidney transplantation. In Danovitch G (ed): Handbook of Kidney Transplantation. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004, pp 72-134.

5 How does the timing of solid organ transplantation affect a patient’s risk for infection?

| Months after transplantation | Type of infection |

|---|---|

| 0-1 | Hospital Derived

Donor-Derived Infections |

Reactivation of Latent Recipient Infections

Reactivation of Latent Donor Derived

Fungal Infections

Atypical Bacterial

Late Viral Infections

VZV, Varicella-zoster virus.

* Generally thought to be the time of greatest immunosuppression.

Modified from Fishman J: Infection in solid organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 357:2601-2614, 2007, and Syndman DR: Epidemiology of infections after solid-organ transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 33(Suppl 1):S5, 2001.

7 What is the initial recommended work-up of suspected infection in the immunocompromised host?

Questions that may provide clinical clues to source of infection:

Type and duration of immunosuppressive medication

Type and duration of immunosuppressive medication

Duration of time since transplantation

Duration of time since transplantation

Sick exposures: family members, co-workers

Sick exposures: family members, co-workers

Recent travel, both in and outside of the country

Recent travel, both in and outside of the country

Eating habits: raw fish, game meat

Eating habits: raw fish, game meat

Hobbies: hunting, fishing, gardening

Hobbies: hunting, fishing, gardening

History of tuberculosis exposure

History of tuberculosis exposure

Use of antimicrobial prophylaxis for viral or bacterial infection

Use of antimicrobial prophylaxis for viral or bacterial infection

Cultures should be obtained from other sites of potential infection: urine, sputum, and stool.

8 What infectious causes should be considered in a patient without a spleen who has suspected sepsis?

10 What is the differential diagnosis in an immunocompromised patient who is seen with a central nervous system (CNS) infection?

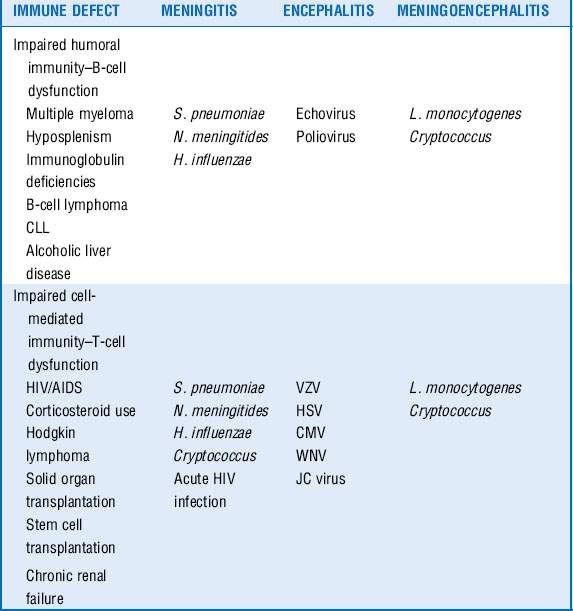

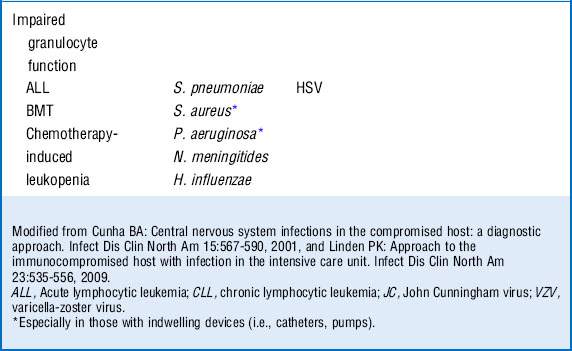

Infections of the CNS are a medical emergency. Although compromised hosts are more susceptible to certain pathogens on the basis of their underlying immune defect, they are also at risk for the same infections as the general population. The clinical presentation of disease may be more subacute in the immunocompromised patients and can offer clues as to the microbiologic entity, especially when the nature of the immune defect of the host is taken into consideration as well. An understanding of the net state of immunosuppression of the patient can provide insight into creating a differential diagnosis of the nature of CNS infection based on clinical presentation. See Table 40-3.

11 What is the initial diagnostic approach to an immunocompromised patient who is seen with a suspected CNS infection?

12 Do special considerations exist for the treatment of meningitis and mass lesions in the immunocompromised host?

15 Describe the initial antibiotic regimen in a patient with febrile neutropenia who is allergic to penicillin

16 What are the most common bacterial causes of community-acquired pneumonia in the immunocompromised host?

17 What is the differential diagnosis for an immunocompromised patient with fever and pulmonary infiltrates?

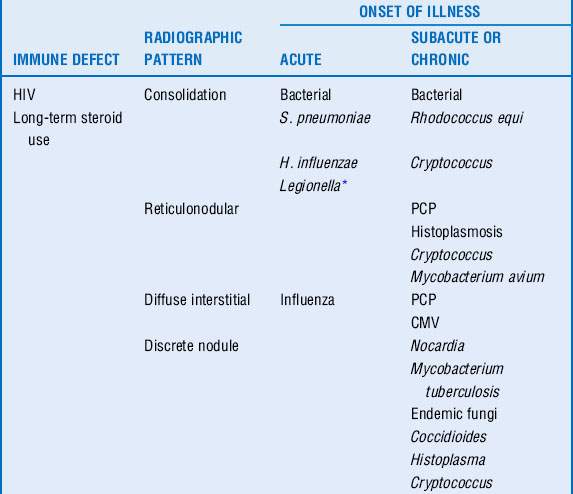

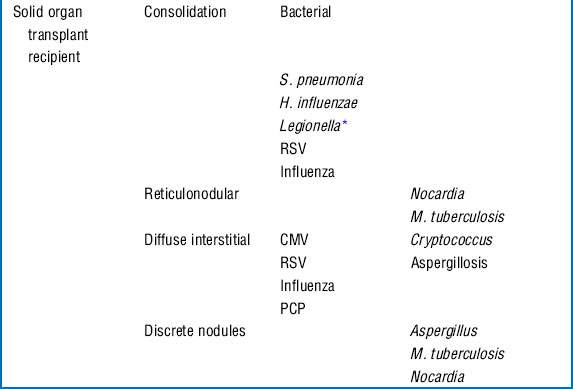

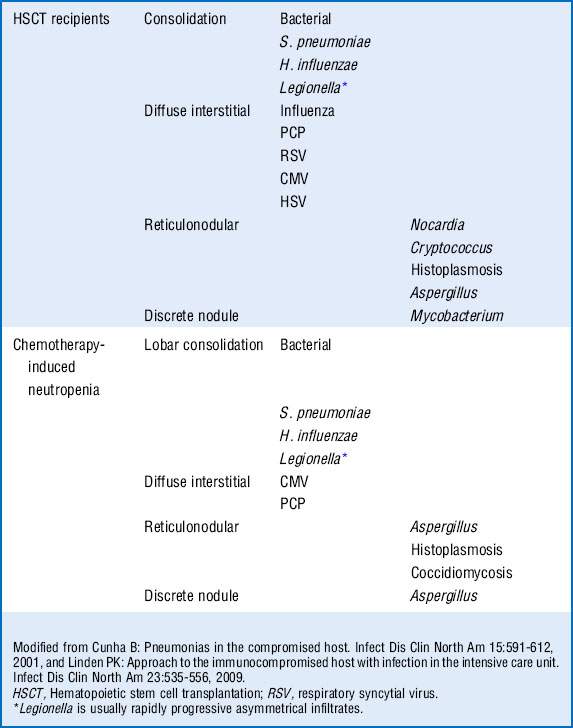

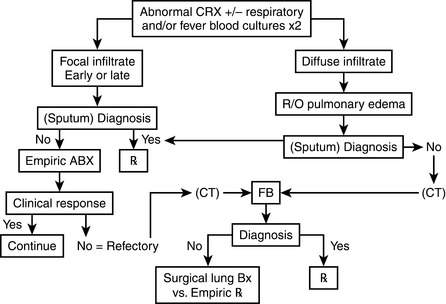

Respiratory compromise in the immunocompromised host carries with it a significant mortality rate with estimates between 30% and 90%. Although the physician must consider noninfectious causes of pulmonary infiltrates (Box 40-1), infectious causes require early recognition and treatment. The differential is based on understanding of the immune defect and characterization of the radiographic pattern of infiltrate, in conjunction with the timing of onset of symptoms. However, it is vital to recognize that no one radiographic appearance is pathognomonic for a specific infection (Table 40-4).

18 What is the role of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and lung biopsy in the diagnosis of pulmonary infiltrates?

19 Describe the clinical course of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) infection and treatment

Although this infection was linked with HIV infection, the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has resulted in effective immune reconstitution, as well as effective prophylactic regimens, thus resulting in a decreased susceptibility to infection. However, we see the incidence of this particular infection increasing among those receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy. Interestingly in patients with HIV the clinical course is usually fairly indolent with complaints of several weeks of cough and increasing dyspnea; at the time of presentation the degree of hypoxemia is usually moderate with little to no peripheral leukocytosis. This is in contrast to the population without HIV, in which the infection can present quite acutely with severe hypoxemia and respiratory failure. Chest radiographs often demonstrate bilateral or asymmetric interstitial infiltrates (more common in the population with HIV). See Table 40-5.

Table 40-5 Treatment of PCP Infection: Moderate to Severe Disease

| Drugs | Dose | Duration and comments |

|---|---|---|

| TMP-SMX* IV and PO | 15-20 mg/kg per day TMP† 75-100 mg/kg per day SMX† |

Recommended duration 21 days |

| Alternatives |

PO, Oral; SMX, sulfamethoxazole; TMP, trimethoprim.

* Some helpful conversions: 16 mg TMP per mL of Bactrim; Bactrim DS = 800 mg TMP/160 mg SMX; Bactrim SS = 400 mg TMP/160 mg SMX.

† Dosing is based on the TMP component.

Modified from Bartlett JG, Gallant JE, Pham PA: Medical Management of HIV Infection. Durham, N.C., Knowledge Source Solutions, 2009, p 449, and Rubin RH, Young LS: Clinical Approach to Infection in the Compromised Host, 4th ed. New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2002, pp 265-289.

20 How is the diagnosis of PCP made?

BAL specimens: BAL with biopsy can make the diagnosis up to 90% of the time. BAL lavage alone is apt to make the diagnosis approximately 50% of the time in patients without HIV but 90% of the time in those with HIV/AIDS because of the higher burden of organisms in this patient population.

BAL specimens: BAL with biopsy can make the diagnosis up to 90% of the time. BAL lavage alone is apt to make the diagnosis approximately 50% of the time in patients without HIV but 90% of the time in those with HIV/AIDS because of the higher burden of organisms in this patient population.

Sputum: Induced (not expectorated) sputum can be useful for diagnosis, especially in patients with AIDS.

Sputum: Induced (not expectorated) sputum can be useful for diagnosis, especially in patients with AIDS.

Biopsy: Histology will show pathognomonic frothy infiltrate that fills the alveoli; organisms can be seen in tissue sections as well. This infiltrate can be confused with hyaline membranes seen in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), although often the two disease states coexist.

Biopsy: Histology will show pathognomonic frothy infiltrate that fills the alveoli; organisms can be seen in tissue sections as well. This infiltrate can be confused with hyaline membranes seen in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), although often the two disease states coexist.

22 What are the most common causes of esophageal disease in those undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy and BMT?

The most common causes of esophageal infection in this patient population are as follows:

23 What is typhlitis, and how is it treated?

Treatment includes IV volume resuscitation and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (see Box 40-2).

24 Describe some of the common causes of community-acquired bacterial enteritis in the immunocompromised patient

25 Describe the most common causes of viral enteritis in the immunocompromised patient

CMV: one of the more common pathogens in the transplant population. Diagnosis requires colonic biopsy. CT findings are nonspecific, and serologic markers such as antigenemia and viral load are unreliable indicators of disease limited to the GI tract.

CMV: one of the more common pathogens in the transplant population. Diagnosis requires colonic biopsy. CT findings are nonspecific, and serologic markers such as antigenemia and viral load are unreliable indicators of disease limited to the GI tract.

Adenovirus: a common cause in both solid organ recipients and BMT recipients. The clinical picture is often that of diarrhea, although bleeding is not uncommon because the virus can lead to colonic ulceration. Dissemination outside of the GI tract can occur leading to pneumonitis, hepatitis, encephalitis, and cystitis.

Adenovirus: a common cause in both solid organ recipients and BMT recipients. The clinical picture is often that of diarrhea, although bleeding is not uncommon because the virus can lead to colonic ulceration. Dissemination outside of the GI tract can occur leading to pneumonitis, hepatitis, encephalitis, and cystitis.

Rotavirus: usually seen in pediatric patients. It can lead to profuse watery diarrhea and is diagnosed by stool PCR testing.

Rotavirus: usually seen in pediatric patients. It can lead to profuse watery diarrhea and is diagnosed by stool PCR testing.

Enterovirus: presenting with watery diarrhea but can progress to meningoencephalitis. It is diagnosed by stool PCR testing.

Enterovirus: presenting with watery diarrhea but can progress to meningoencephalitis. It is diagnosed by stool PCR testing.

HSV: can lead to ulcerations in the upper and lower GI tract.

HSV: can lead to ulcerations in the upper and lower GI tract.

27 Should antirejection medications be altered for the solid organ transplant recipient with severe sepsis?

Important facts to consider when considering reduction of immunosuppression:

Mortality associated with loss of allograft: Graft loss in heart or liver transplant recipients may be very different from graft loss in those who have undergone pancreas or kidney transplantation. If other modalities can be used, that is, insulin or hemodialysis, then, although not ideal, the graft may be able to be sacrificed in the setting of life-threatening infection.

Mortality associated with loss of allograft: Graft loss in heart or liver transplant recipients may be very different from graft loss in those who have undergone pancreas or kidney transplantation. If other modalities can be used, that is, insulin or hemodialysis, then, although not ideal, the graft may be able to be sacrificed in the setting of life-threatening infection.

Use of steroids: In the setting of acute infection, rapid withdrawal or taper of steroids may lead to adrenal insufficiency complicating the patient’s hemodynamics. In addition, the use of steroids may be clinically indicated for treatment of the underlying infection or sequelae thereof (i.e., PCP or cerebral edema associated with toxoplasmosis).

Use of steroids: In the setting of acute infection, rapid withdrawal or taper of steroids may lead to adrenal insufficiency complicating the patient’s hemodynamics. In addition, the use of steroids may be clinically indicated for treatment of the underlying infection or sequelae thereof (i.e., PCP or cerebral edema associated with toxoplasmosis).

Key Points Immunocompromised Host

1. The net state of immunosuppression is critical in assessing a patient’s risk for infection.

2. The longer the duration of neutropenia, the greater the risk for invasive fungal disease.

3. Individuals without a spleen are at risk for infection with encapsulated organisms.

4. The greatest degree of immunosuppression in solid organ transplant recipients is 1 to 6 months after transplantation.

5. Early antimicrobial therapy is essential in patients with neutropenic fever.

1 Baden L.R., Maguire J.H. Gastrointestinal infections in the immunocompromised host. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:639–670.

2 Bartlett J.G., Gallant J.E., Pham P.A. Medical Management of HIV Infection. Durham: N.C., Knowledge Source Solutions; 2009. p 449

3 Cunha B. Pneumonias in the compromised host. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:591–612.

4 Cunha B.A. Central nervous system infections in the compromised host: a diagnostic approach. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:567–590.

5 Fishman J.A. Pneumocystis carinii and parasitic infections in the immunocompromised host. In: Rubin R.H., Young L.S. Clinical Approach to Infection in the Compromised Host. 4th ed. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002:265–325.

6 Fishman J.A. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2601–2614.

7 Freifeld A.G., Bow E.J., Sepkowitz K.A., et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e56–e93.

8 Kotloff R.M., Ahya V.N., Crawford S.W. Pulmonary complications of solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:22–48.

9 Leather H.L., Wingard J.R. Infections following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:483–520.

10 Linden P.K. Approach to the immunocompromised host with infection in the intensive care unit. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2009;23:535–556.

11 Lyons R.W. Approach to the immunocompromised host. In: Grace C., ed. Medical Management of Infectious Disease. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2003:661–665.

12 Mandell G.L., Bennett J.E., Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. pp 3520-3530

13 Rubin R., Schaffner A., Speich R. Introduction to the Immunocompromised Host Society Consensus Conference on Epidemiology, Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Solid-Organ Transplant Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(Suppl 1):S1–S4.

14 Rubin R.H., Young L.S. Clinical Approach to Infection in the Compromised Host, 4th ed. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. pp 265-289

15 Sumaraju V., Smith L.G., Smith S.M. Infectious complications in asplenic hosts. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:551–565.

16 Syndman D.R. Epidemiology of infections after solid-organ transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(Suppl 1):S5.

17 Tasaka S., Hasegawa N., Kobayashi S., et al. Serum indicators for the diagnosis of pneumocystis pneumonia. Chest. 2007;131:1173–1180.

18 White P. Evaluation of pulmonary infiltrates in critically ill patients with cancer and marrow transplant. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17:647–670.