4

Imaging in obstetrics and gynaecology

Introduction

Imaging plays an important role in both obstetrics and gynaecology. Ultrasound is extremely valuable at all stages of pregnancy: early in pregnancy for viability and establishing gestation, mid-pregnancy to look for fetal abnormality and later in pregnancy, for growth, well-being and presentation. Ultrasound is also very useful in gynaecology to assess both the uterus and the ovaries, and further information can be obtained with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if required. Other uses of imaging will also be discussed.

Obstetrics

Fetal assessment

Ultrasound is an excellent modality for pregnancy. In particular, it has a rapid acquisition time (useful when movement is present), is portable and convenient (can be used in labour ward if required), is almost certainly extremely safe and is socially acceptable. Its accessibility, however, occasionally means that there is a temptation for untrained practitioners to use it and, although good images can easily be obtained, interpretation is often quite subtle – even in simple terms of orientation.

When scanning in pregnancy, it is important to determine the number of fetuses, their presentation and position, the presence of fetal heart activity and the position of the placenta. The rest of the scan will then depend on gestation: gestation and viability in early pregnancy (Chapter 10) nuchal measurements between 11 and 14 weeks; fetal abnormality between 18–21 weeks (Chapter 33); and growth and well-being for the remainder of pregnancy (Chapter 35). Finally, cervical length (Chapter 37) can be used to predict the likelihood of pre-term delivery.

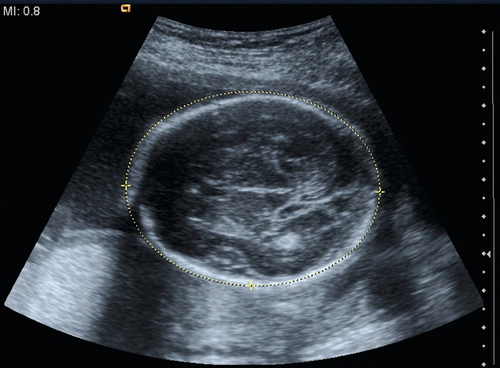

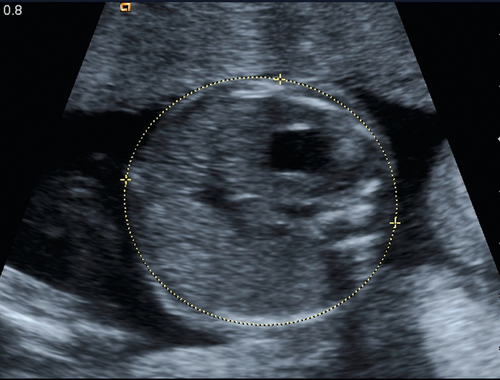

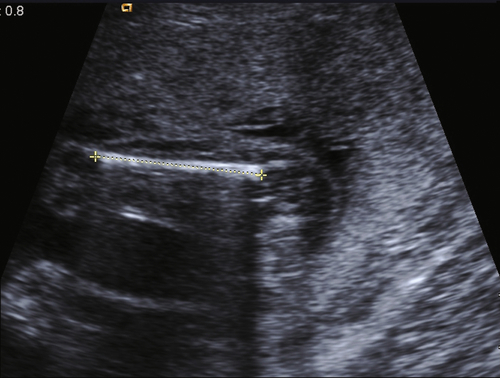

Growth measurements are made at specific anatomical sites to ensure reliability and reproducibility. The head, abdominal circumference and femur length are usually measured, and can be charted to quantify growth (Figs 4.1–4.3). It is important to recognize that, even in the most skilled hands, these measurements have a margin for error and that clinical decisions should not be based on small changes on the charts. Fetuses who are apparently very large may well deliver normally, and babies who appear small may simply be small-for-dates rather than growth-restricted (Chapter 35). Liquor volume and fetal activity are useful in assessing fetal well-being in the short term, and Doppler studies of the uterine artery, umbilical artery, middle cerebral artery and ductus venosus, in the medium and longer term. Any decisions to act on such findings depend on a careful assessment of the full picture.

The vast majority of fetal assessments can be made using 2D ultrasound. There is some role for 3D ultrasound, but its use remains limited, despite the social interest in the images (Fig. 4.4). MRI also has a use for specific fetal conditions (e.g. clarification of brain abnormalities or assessment of diaphragmatic herniae). MRI can also be used to clarify the diagnosis in cases of suspected placenta accreta (Chapter 34).

Maternal assessment

If a potentially serious condition is suspected in the mother, it is important to investigate as fully as possible. This applies particularly to venous thromboembolic disease (Chapter 30) but also to many other conditions, including abnormal neurological presentations, cardiac problems or suspected malignancy. This may result in exposure to radiation and the dose must be kept to a minimum.

Risks of radiation

The radiation dose to a fetus from any of the commonly used diagnostic tests is small, and is extremely unlikely to increase the chances of fetal loss, growth restriction or fetal malformation. Fetal radiation, however, may very slightly increase the chance of childhood cancer, as radiation during this time of rapid cell replication may increase the chance of mutations. This risk is determined by the radiation dose during development, which varies from around 0.01 mGy for a chest X-ray to 10 mGy for a CT of the abdomen; these doses correspond to a risk of < 1 in 1 000 000 to 1 in 10 000 per examination, respectively, which remain very small in relation to a background risk of 1 in 500. While the risks of any examinations have to be carefully considered, it is important not to miss the opportunity to diagnose potentially treatable conditions.

Gynaecology

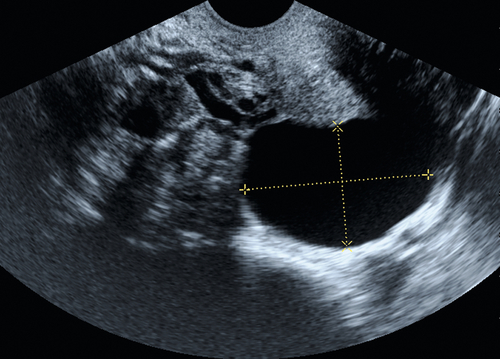

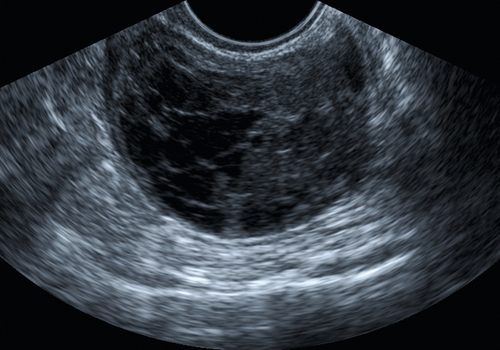

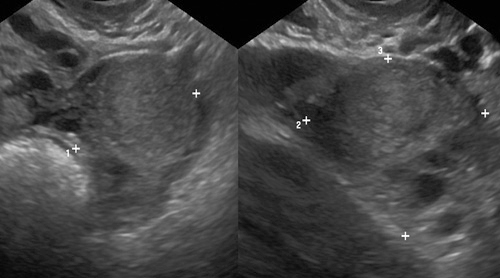

As with obstetrics, the most common imaging technique used in gynaecology is ultrasound. Both the transabdominal and transvaginal routes allow an excellent assessment of the uterus, and the adnexae, as shown in Figures 4.5–4.7.

X-rays have a relatively limited role in gynaecology, although contrast studies are useful to assess tubal patency (Fig. 9.3).

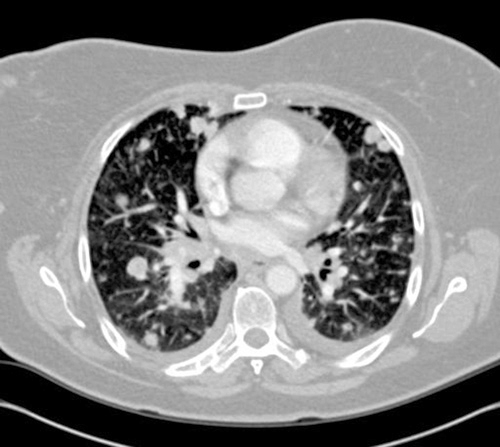

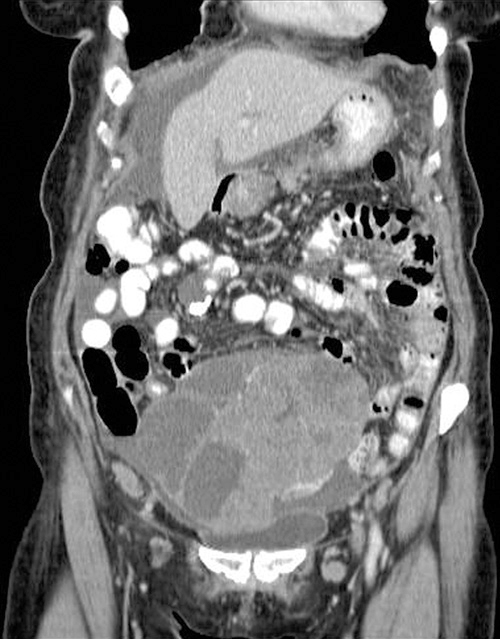

CT scanning is also used, either to visualize the pelvic organs more clearly or to provide a fuller assessment of the abdomen in suspected malignancy (Fig. 4.8) or for more distant metastatic disease (Fig. 4.9). MRI provides a better assessment of cervical malignancy (Fig. 4.10) than CT, and is probably better at characterizing adnexal lesions in general.

Fig. 4.8CT scan of ovarian carcinoma with ascites.

The pelvic mass contains both solid and cystic components.