2 Imaging for orthopaedics

Imaging has now assumed a greater role in the management of patients with orthopaedic disease than ever before. For many years imaging was limited to the use of plain radiographic films which really only gave useful information on bony structures. Over the past 25 years orthopaedics has benefited greatly from newer imaging modalities which are able to give much greater information, not only on the bony structures, but also of the surrounding soft tissues. While plain films remain the mainstay of imaging in trauma, in other orthopaedic conditions they are now less important. Cross-sectional imaging, in particular the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has now become the most important imaging modality for many orthopaedic conditions. MRI allows detailed identification of the soft-tissue structures in and around joints and for this reason has assumed a very prominent position in imaging of orthopaedic patients.

COMPUTERISED TOMOGRAPHY (CT)

CT is a technique that utilises X-rays, but acquires multiple thin slices axially through the area of interest. With the advances in digital technology modern CT scanners can now acquire this data very rapidly. Current models in use can obtain 16 slices simultaneously, while new machines will be able to acquire 64 and even 256 slices at a time. The result is a stack of very thin radiographic images, usually about 1 mm in thickness. These can be manipulated by the CT computer to generate images in any plane with excellent detail. Typically these images are reformatted into coronal and sagittal planes so that images are similar to looking at AP and lateral radiographs (Fig. 2.1). These images can be acquired in only a few seconds and the reconstructions are also available within a similar short time. Modern scanners can also rapidly reconstruct a three-dimensional model of the scanned area (Fig. 2.2). The commonest role of CT in orthopaedics is assisting in the management of trauma patients with complex fractures. While the fracture is usually easily visualised on plain radiographs, the exact position, number and size of the fracture fragments may be more difficult to identify correctly. This is where CT and its multiplanar capability is of most use in orthopaedic patient management. Typical areas where CT is of most value are in the assessment of fractures in complex anatomical sites, such as the spine, pelvis, tibial plateau and calcaneus. Fracture treatment planning is greatly aided by the multiple views that can be obtained of these complex injuries and in selected cases three-dimensional reconstructions can also add useful information.

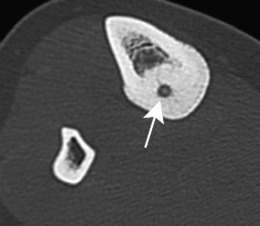

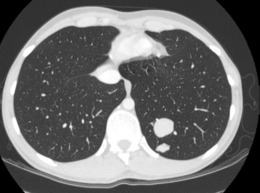

Non-traumatic conditions where CT can be useful are the evaluation of bone- and cartilage-based tumours. Although MRI is the principal method used for the anatomical staging of these tumours, CT may add further useful information regarding the extent of the ossifying or calcified portions of these tumours which an MR scan can underestimate (Fig. 2.3). Another example is osteoid osteoma, where a CT scan provides the diagnostic finding of a very small central sclerotic nidus (Fig. 2.4). A CT scan is also valuable for the full staging of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas, where it is used routinely to detect the presence of lung metastases (Fig. 2.5).

Fig. 2.3 A MRI scan of a very large mass arising from the pelvis and occupying a large part of the abdomen. B A coronal reformatted CT of the same lesion. This shows the bony origin and the bone content of the tumour which is not well seen on the MRI scan.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING (MRI)

The T1 images show fat as white, bone and tendons as black, with muscle and water appearing grey (Fig. 2.6A). A T2 image of the same structure is most easily recognised because water is seen as white (Fig. 2.6B). This is useful in the detection of fluid structures such as cerebrospinal fluid in the spinal canal and cystic masses in the soft tissues. If the same image then has fat saturation, the fat becomes black leaving even small amounts of fluid as the only white areas on the image. This means that subtle oedema in muscle or bone can be easily identified.

Fig. 2.6 A A sagittal T1 weighted image of the lumbar spine. Note that the CSF in the spinal canal is dark grey. B Sagittal T2 weighted image of same patient. Here the CSF is now white. Fluid appears white on T2 weighted images. The intervertebral discs are healthy as they can be seen to contain high signal fluid within the nucleus pulposus.

Further information can be obtained by using MR contrast agents. These substances are injected intravenously and are most commonly compounds derived from gadolinium, a heavy metal which alters the signal characteristics of various structures, particularly those with a large blood supply. Further scans obtained after injection of this contrast medium may give helpful additional information in selected cases. Typically this is used for the assessment of tumours, infection and post operative patients following spinal surgery (Fig. 2.7).

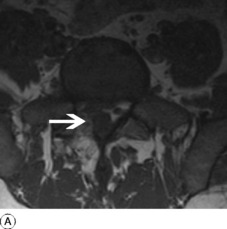

MRI is particularly helpful where the abnormality is confined to soft-tissue structures and is most commonly used for evaluation of disease and injury in the spine and knee. In the spine, MRI can identify the intervertebral discs and individual nerve roots, making it the investigation of choice for patients with suspected disc herniation causing nerve root compression (Fig. 2.8). It can also be used to identify spinal stenosis, disc space infection and spinal tumours.

Fig. 2.8 A Sagittal T2 weighted image of lumbar spine. There is a large herniation of the L4/5 disc. B Axial scan through the disc space showing disc material has herniated into the left side of the spinal canal and compressed the left L5 nerve (compare with normal nerve on the right). By convention axial images are viewed as if looking from the patient’s feet. Thus, the patient’s right is on the left of the image and vice versa.

In patients with knee pain, MRI is highly accurate in diagnosing patients with meniscal tears and can distinguish between degenerate oblique tears and the less common bucket handle tears. It is also valuable in detecting injuries of the cruciate and collateral ligaments following trauma to the knee joint.

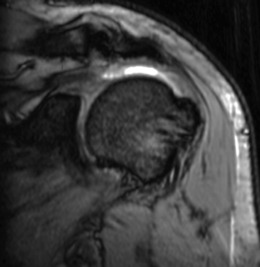

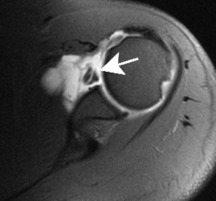

In the shoulder MR scans are increasingly used to identify degenerative tendinopathy of the rotator cuff muscles and tears of the individual tendons (Fig. 2.9). Around the ankle it has proved useful in the diagnosis of tears and degeneration of the Achilles tendon, as well as for osteochondral fractures of the talar dome, and injuries to the collateral ligaments of the ankle and subtalar joints.

MRI is particularly sensitive for imaging the bone marrow because of its high fat content, so that any disease associated with abnormal bone marrow will be identified. These include malignant primary bone tumours, as well as metastases and myeloma, all of which are marrow-based disorders (Fig. 2.10). Infection of bone, avascular necrosis and stress fractures, only cause changes visible on plain radiographs late in the disease process, but MR scans will identify all of these conditions at an early stage.

ULTRASOUND

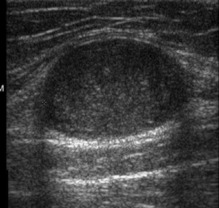

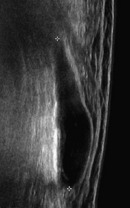

Ultrasound has a useful role in orthopaedic imaging. Ultrasound machines are readily available in almost every hospital. The scan only takes a short time, but its value and reliability is very operator dependent. Like MRI, there are no known dangerous side effects associated with the use of ultrasound. While little or no information is obtained from bony structures, ultrasound can visualise the soft tissues in many areas. Particular structures which are well seen on ultrasound are tendon and muscles. Thus suspected abnormalities of the patellar tendon, Achilles tendon and rotator cuff of the shoulder can all be diagnosed by this technique (Fig. 2.11). Muscle tears are easily identified as are their associated haematomas. In skilled hands evaluation of tendon lesions around the hand and wrist can be assessed and some operators are also able to identify ligamentous injuries around the elbow and ankle. Ultrasound is also of use in the evaluation of soft-tissue masses (Fig. 2.12), and fluid-filled structures such as Baker’s cyst of the knee (Fig. 2.13), which can be diagnosed reliably by this technique alone.

ISOTOPE SCANNING

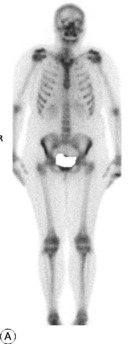

Isotope bone scanning requires the intravenous injection of a radioactive tracer, usually technetium (99mTc), linked to a molecule such as disphosphonate which will become incorporated into areas of high bone turnover where there is increased osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity. The bone-seeking radioisotope is injected intravenously and the emitted rays are charted with a gamma camera. After injection of the isotope there is an immediate diffusion of isotope into the bone matrix from the blood: thus an increased uptake of isotope locally in the skeleton denotes hyperaemia of the bone. This is seen on a scan obtained a few minutes after injection (early phase). It will only be seen in conditions with markedly increased blood flow to the area, typically in acute infection. Within 2–4 hours (late phase) the isotope is taken up by active bone-forming cells, increased uptake thus denoting increased osteogenic activity. However, this is non specific as osteoclastic activity is increased by many disease processes, including the site of healing fractures as well as tumours and bone infection. Nevertheless, taken in conjunction with the history and clinical findings, areas of increased uptake can be identified and the likeliest cause suggested. The commonest use for isotope scanning is in identifying the site of bony metastases (Fig. 2.14). Bone scanning will provide images of the complete bony skeleton and this is its major advantage. It is often necessary to supplement the scan with plain radiographs of the areas showing abnormal increased isotope uptake. An example where this is required is when the plain films may be able to identify benign causes of increased isotope uptake and distinguish these from tumour (Fig. 2.15). Isotope bone scanning may also have a role in the diagnosis of infections of bone or joint, primary bone tumours, osteoid osteoma, and stress fractures.

POSITRON EMISSION TOMOGRAPHY (PET CT)

Positron emission tomography is the newest addition to imaging, now usually combined with a CT scan. In essence it is an isotope imaging technique, but one which uses a more complex isotope which emits positrons. The isotope can be linked to various molecules but the one most commonly used is fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), which accumulates in areas of altered glucose metabolism. The localisation of the site of this uptake is improved by fusing the isotope image with that of a CT scan acquired at the same time. The most common application is in the identification of active tumours and although its role in orthopaedics is currently limited, it may have a future role in the evaluation of bone and soft-tissue tumours. The technique may also be useful in the evaluation of infection around joint replacements but as yet this is not well defined. The technology for PET CT is currently limited to a few specialist centres and is not generally available.

ARTHROGRAPHY

Arthrography is a technique where an X-ray contrast is injected directly into a joint to enable visualisation of the joint surfaces and structures within the joint which would otherwise not be visible on an X-ray. This is being used much less frequently than in the past, as MRI and ultrasound can now often visualise the structures of interest without the need for any contrast. Where it is still used, it is usually in conjunction with MRI and occasionally CT. The resultant MR arthrogram can give even greater detail about intra-articular structures than plain MRI. The commonest indications are; in the shoulder to demonstrate disruption of the glenoid labrum in patients with recurrent dislocation or instability (Fig. 2.16), and in the hip when looking for evidence of impingement and labral tears.

ANGIOGRAPHY (ARTERIOGRAPHY)

This is a specialised technique which is now used only infrequently in orthopaedics. The two major indications are trauma and tumour. Following trauma with a severely displaced bone fracture, angiography may be indicated to evaluate associated vascular injury, such as may occur in the pelvis and humerus. Note that angiography can now be carried out using CT and MRI, as well as by conventional intra-arterial catheterisation. In the evaluation of tumours, arteriography may be useful to delineate the extent of the vascular supply, or the relationship of vascular structures to the tumour, to enable safe surgical planning. In both circumstances the use of conventional catheterisation for angiography has the advantage of being able to carry out therapeutic procedures. In life-threatening haemorrhage, embolisation or stenting can be undertaken at the site of vascular damage. In cases of highly vascular tumours, preoperative embolisation of the tumour may reduce intraoperative haemorrhage. This is most commonly used in patients with metastasic renal tumour as these are generally highly vascular and prone to bleed profusely at surgery without prior embolisation (Fig. 2.17).