131 Hypothermia and Frostbite

• Accidental (primary) hypothermia occurs when the ambient temperature outstrips a person’s ability to thermoregulate.

• Secondary hypothermia is due to an underlying medical problem that alters thermoregulation.

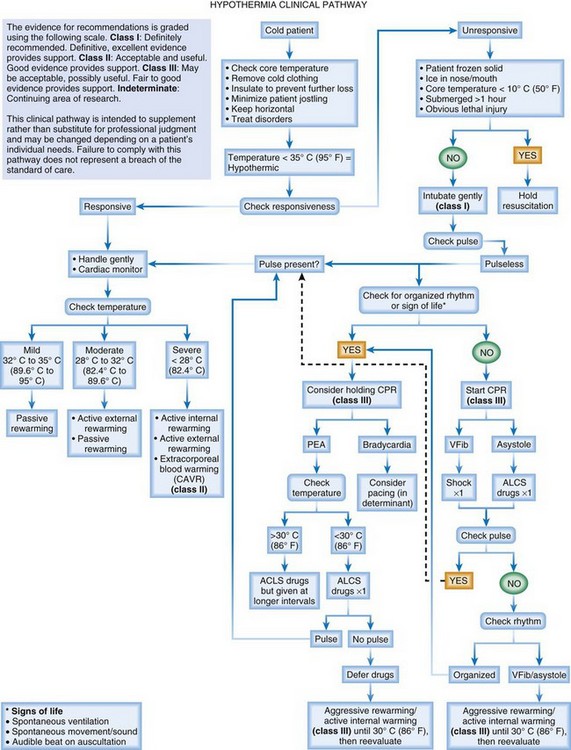

• Mild hypothermia is treated by passive external rewarming, moderate hypothermia by a combination of passive and active external and active internal rewarming, and severe hypothermia by active external and active internal rewarming techniques.

• For patients without a pulse or blood pressure, aggressive, invasive measures should be pursued.

• One should hesitate to declare death in a hypothermic patient. Consider rewarming to a temperature of 32° C to 35° C.

• Frostbite remains a clinical diagnosis and needs to be distinguished from nonfreezing injuries (frostnip, pernio, and trench foot).

• The cornerstone of therapy is rapid rewarming in a circulating bath of heated water.

• In all aspects of care a subsequent “freeze-thaw-freeze” cycle must be avoided.

• Additional therapies involve the use of antiprostaglandins, both topical and systemic, and possibly thrombolytics.

• The full extent of frostbite injury can take weeks to become evident.

Perspective

Accidental hypothermia is responsible for approximately 700 deaths per year in the United States.1 It primarily affects those least able to ward off the effects of cold weather: the very young, the very old, and the poor, disabled, pharmacologically inquisitive, environmentally adventurous, and mentally ill. Urban people are common victims. Hypothermia can occur in many latitudes, with episodes reported even in Florida.2 It occurs when a person’s ability to generate heat and remain warm is outstripped by the ambient temperature.

Epidemiology

Accidental hypothermia is generally manifested as progression from an initial state of catecholamine release and stimulation (mild hypothermia) to one marked by a predictable slowing of metabolism and all critical body functions to the extent that patients may appear dead. The profound physiologic changes and metabolic slowing all reverse with rapid rewarming, and reports of remarkable neurologically intact survival despite hours of pulselessness and resuscitation are not infrequent. This has given rise to the adage “No one is dead until they are warm and dead.” Not surprisingly, there is little strong scientific evidence for treatment recommendations because trials cannot be conducted. The medical literature is composed mostly of animal experiments, case reports and series, and retrospective reviews. Still, rational approaches can be inferred from the extant literature for this uncommon but serious problem (Table 131.1).

| LEVEL OF HYPOTHERMIA | CORE TEMPERATURE (° C) |

|---|---|

| General | >35 |

| Mild | 32-35 |

| Moderate | 28-32 |

| Severe | <28 |

Hypothermia

Pathophysiology

Mechanisms of Heat Loss

The mechanisms of heat loss are as follows:

• Radiation of heat occurs when the ambient temperature is less than body temperature and heat is lost directly to the environment via electromagnetic radiation.

• Conduction is heat transfer from one (warmer) solid to another (cooler) when they are in contact.

• Convection is loss of heat from a surface to a (usually moving) gas or fluid, typically air or water. It can be considered an adjunct to conduction.

• Evaporation causes heat loss through the energy required to vaporize water (i.e., sweat).

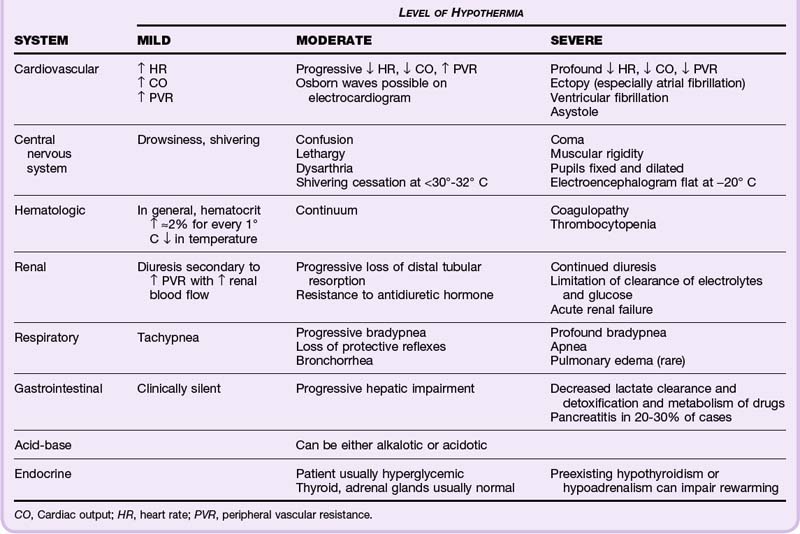

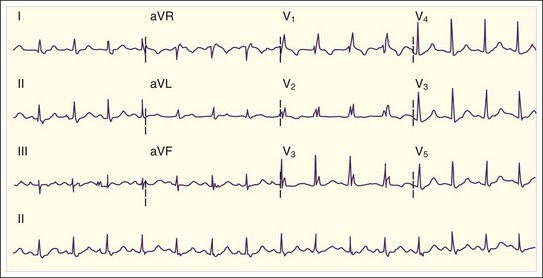

As a person cools, a fairly predictable procession of pathophysiologic changes occurs, as seen in Table 131.2 and Figure 131 .1.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The critical element of the diagnosis of hypothermia is accurate measurement of core temperature. Several methods exist, all of which have potential drawbacks (Table 131.3). Laboratory and physiologic changes are correlated with the temperature. For example, a normal hematocrit value in a severely hypothermic patient should prompt concern for hemorrhage because the hematocrit should rise in a predictable fashion with ever-lowering temperature. Alternatively, arterial blood gas values should be interpreted as though the patient is normothermic (the alpha-stat method) and not corrected for the actual core temperature (the pH-stat method). Evaluation for infection, metabolic derangement, and cardiac, neurologic, renal, and other organ system abnormalities is important because comorbid conditions are common as a cause, a consequence, or coincidence of hypothermia.

| METHOD | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Esophageal probe | Easy to insert |

| Falsely high temperature readings possible with warmed oxygen via an endotracheal tube | |

| Rectal probe | Insert to 15-20 cm |

| If the probe is in or surrounded by cold stool, temperature recordings will lag behind true changes | |

| Temperature-recording Foley catheter | Inflowing cold urine may falsely lower temperature recordings |

| Pulmonary artery catheter | Most accurate and most invasive method |

| Higher potential for iatrogenic injury, especially ventricular fibrillation in cold, irritable myocardium |

Treatment

Severe Hypothermia

• Heated, humidified oxygen (40° C to 45° C) administered via face mask or endotracheal tube; it primarily serves to prevent additional heat loss.

• Administration of heated IV fluids (40° C to 42° C) adds negligible heat overall but does aid in preventing further heat loss.

• Gastric or bladder lavage (or both) via nasogastric tube and Foley catheter is relatively easily accomplished; however, the small volume of these cavities limits the effectiveness of these modalities.

• Peritoneal lavage with prepackaged dialysate or standard crystalloid fluids heated to about 45° C. This method is quicker if two catheters, one for afferent flow and one for efferent flow, are used. Rewarming rates average 2° C to 3° C per hour.3,4

• Closed thoracic cavity lavage (pleural lavage) of the left hemithorax is done with two 36-French thoracostomy tubes and isotonic fluid heated to about 42° C. Large volumes are required. The afferent tube is placed in the second intercostal space (ICS) in the midclavicular line. The efferent tube is placed in the usual location, the fourth or fifth ICS in the midaxillary line. Fluid is literally poured in by hand, infused with a large (60-mL) syringe, or administered directly with a rapid infuser (the hub of the rapid infuser fits snugly into the bore of a 36-French chest tube). Rewarming rates average about 3° C per hour.5,6

• Left thoracotomy with mediastinal irrigation and internal cardiac massage is quite invasive with high attendant morbidity. It is very effective and self-explanatory and has rewarming rates as high as 5° C to 6° C per hour.7,8

• Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is the definitive method for rewarming. It is rapid, with rewarming rates of 9° C per hour or higher achieved, and supports blood pressure; however, CPB also requires specialized equipment and personnel that are not readily available in most hospitals.9,10

The use of medications, particularly cardioactive medications and vasopressors, is theoretically unappealing and thought to be potentially dangerous in a patient with a core temperature lower than 30° C, primarily because of decreased metabolism, which can lead to toxic levels. Similarly, defibrillation is less likely to be effective at temperatures lower than 30° C. However, citing the solely theoretic basis of these concerns, the 2010 American Heart Association guidelines now state that in patients with persistent ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia after a single shock it may be “reasonable to perform further defibrillation attempts according to the standard BLS [basic life support] algorithm concurrent with rewarming strategies.” Furthermore, regarding medication administration “it may be reasonable to consider administration of a vasopressor during cardiac arrest according to the standard ACLS [advanced cardiac life support] algorithm concurrent with rewarming strategies.”11 It is clear that very little is known about the utility of defibrillation and administration of vasoactive medications in patients with hypothermic cardiac arrest. Providers will have to decide each case on an individual basis and be guided by any response to the therapy used.

Next Steps in Care

Numerous case reports have described neurologically intact survival after prolonged, severe hypothermia with cardiac arrest.7,12 A serum potassium level higher than 10 mmol/L has been postulated to be a marker of irreversible cell and therefore patient death13; however, another case report has called this approach into question.14 Pronouncement of death in a severely hypothermic patient should be made with reluctance until the patient’s core temperature has been warmed to higher than 30° C to 32° C and signs of life remain absent.

A reasonable approach to the hypothermic patient is presented in Figure 131.2.

Fig. 131.2 Algorithmic approach to patients with hypothermia.

(From EB Medicine, publisher of EM Critical Care and Emergency Medicine Practice: Mulcahy AR, Watts MR. Accidental hypothermia: an evidence-based approach. Emerg Med Prac 2009;11:1–24. Available at www.ebmedicine.net.)

see Figure 131.2, Algorithmic Approach to Patiens with Hypothermia, online at www.expertconsult.com

Frostbite

Pathophysiology

Frostbite is a freezing injury to tissues. During this process it is believed that deposits of ice crystals causing interstitial, cellular, and vascular endothelial cell damage are one part of the pathophysiologic process.15 The vascular endothelial damage results in activation of the clotting cascade with resulting thrombosis, which leads to hypoperfusion, ischemia, and eventually tissue necrosis. The prominence of the clotting that can cause vascular occlusion can be seen on angiography and is the basis for the concept of treating selected patients with thrombolysis.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The classic victim of frostbite has either a dusky or a white affected area that is brawny to solid in texture, insensate, and without capillary refill. Variations are time dependent, and patients seen in delayed fashion may have blisters that are either hemorrhagic or clear and even some tissue loss or frank necrosis already evident. Classification systems exist for frostbite, but they are controversial and are also problematic for the emergency physician because the initial clinical appearance can be misleading and it takes time for the full extent of the damage to become clear. It is simpler and more realistic to start to treat the affected part and consult surgeons for ongoing wound care and treatment (Fig. 131.3).

Treatment

For a concise summation of nonfreezing injuries, see www.expertconsult.com

Frostnip is a superficial freezing injury that appears pale and can be associated with discomfort. It resolves with rewarming without sequelae

Pernio (chilblains) is due to repeated, intermittent exposure to wet, nonfreezing temperatures. Localized edema, erythema, nodules, plaques, cyanosis, and possibly vesicles and ulcerations appear up to 12 hours after exposure. Burning paresthesias and itching may be present, and rewarming can result in the formation of bluish nodules. Care is supportive and consists of rewarming, bandaging, and elevation. Nifedipine, pentoxifylline, or limaprost has been advocated as potential therapy. Topical and oral corticosteroids may be useful.

Trench foot is direct soft tissue injury secondary to prolonged immersion in cold water. It develops slowly, but the damage, though initially reversible, may become permanent if not treated. Early in the course, paresthesias develop in a pale, mottled, insensate, and possibly pulseless foot. It becomes hyperemic after rewarming, with return of sensation (proximal more than distal) and severe burning pain. Edema and blisters can form, and in severe cases, tissue sloughing and gangrene can develop. Prevention is paramount, but when it does occur, trench foot is treated supportively much like chilblains.

Hospital Management

Prophylactic antibiotics are controversial. Penicillin G has been advocated. Additionally, ibuprofen, 400 mg by mouth twice daily, is recommended in an attempt to interrupt the arachidonic acid cascade.15,16 Both catheter-directed intraarterial and systemic thrombolytic therapies have been used with impressive success in preventing amputations (Figs. 131.4 and 131.5). This novel therapy holds considerable promise but does have several limitations, including restriction to patients initially seen within 24 hours of the injury and risk for bleeding.17,18

Fig. 131.5 Angiogram of the foot shown in Figure. 131.3 after approximately 30 hours of tissue plasminogen activator infusion showing restoration of perfusion.

Most recently, a small, randomized trial of frostbite therapies showed remarkable success with intravenous iloprost, a prostacyclin (no digit amputations), over an IV nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (≈40% digit amputation rate) or recombinant tissue plasminogen activator plus iloprost (≈3% digit amputation rate).19 Whether this promising success can be repeated and confirmed elsewhere remains to be seen.

Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546–551. discussion 551–553

Danzl DF, Pozos RS, Auerbach PS, et al. Multicenter hypothermia survey. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:1042–1055.

Mulcahy A, Watts M. Accidental hypothermia: an evidence-based approach. Emerg Med Pract. 2009;11:1–24.

Murphy JV, Banwell PE, Roberts AH, et al. Frostbite: pathogenesis and treatment. J Trauma. 2000;48:171–178.

Walpoth BH, Walpoth-Aslan BN, Mattle HP, et al. Outcome of survivors of accidental deep hypothermia and circulatory arrest treated with extracorporeal blood warming. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1500–1505.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hypothermia-related deaths—Utah, 2000, and United States, 1979–1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(4):76–78.

2 Danzl DF, Pozos RS, Auerbach PS, et al. Multicenter hypothermia survey. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:1042–1055.

3 Troelsen S, Rybro L, Knudsen F. Profound accidental hypothermia treated with peritoneal dialysis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1986;20:221–224.

4 Pickering BG, Bristow GK, Craig DB. Case history number 97: core rewarming by peritoneal irrigation in accidental hypothermia with cardiac arrest. Anesth Analg. 1977;56:574–577.

5 Hall KN, Syverud SA. Closed thoracic cavity lavage in the treatment of severe hypothermia in human beings. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:204–206.

6 Winegard C. Successful treatment of severe hypothermia and prolonged cardiac arrest with closed thoracic cavity lavage. J Emerg Med. 1997;15:629–632.

7 Brunette DD, Biros M, Mlinek EJ, et al. Internal cardiac massage and mediastinal irrigation in hypothermic cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:32–34.

8 Brunette DD, McVaney K. Hypothermic cardiac arrest: an 11 year review of ED management and outcome. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:418–422.

9 Walpoth BH, Locher T, Leupi F, et al. Accidental deep hypothermia with cardiopulmonary arrest: extracorporeal blood rewarming in 11 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1990;4:390–393.

10 Walpoth BH, Walpoth-Aslan BN, Mattle HP, et al. Outcome of survivors of accidental deep hypothermia and circulatory arrest treated with extracorporeal blood warming. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1500–1505.

11 Vanden Hoek TL, Morrison LJ, Shuster M, et al. Part 12: cardiac arrest in special situations: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122:S829–S861.

12 Hauty MG, Esrig BC, Hill JG, et al. Prognostic factors in severe accidental hypothermia: experience from the Mt. Hood tragedy. J Trauma. 1987;27:1107–1112.

13 Schaller MD, Perret CH. Hyperkalemia: a prognostic factor during severe hypothermia. JAMA. 1990;264:1842–1845.

14 Dobson JA, Burgess JJ. Resuscitation of severe hypothermia by extracorporeal rewarming in a child. J Trauma. 1996;40:483–485.

15 Murphy JV, Banwell PE, Roberts AH, et al. Frostbite: pathogenesis and treatment. J Trauma. 2000;48:171–178.

16 McCauley RL, Hing DN, Robson MC, et al. Frostbite injuries: a rational approach based on the pathophysiology. J Trauma. 1983;23:143–147.

17 Twomey JA, Peltier G, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005;59:1350–1354. discussion 1354–5

18 Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546–551. discussion 551–553

19 Cauchy E, Cheguillaume B, Chetaille E. A controlled trial of a prostacyclin and rt-PA in the treatment of severe frostbite. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:189–190.